Malibu and Me, Part 2: 1993

There were hilarious moments. There were infuriating moments. There were terrifying moments. But there were never dull moments. Working on staff at Malibu Comics at this particular time gave me a front row seat to one of the most turbulent years in the industry. It also positioned me for greater things I couldn’t have imagined before I overturned my life to be there. Captured here are some of the moments I will never forget.

(Side note: when I use the terms “us” and “we,” I’m referring to my posse and me. The art department. Brothers in ink.)

Videodrome

As I mentioned in part 1, the company set up its own video department, called Malibu Films. Darren Doane and Ken Daurio ran it. I was unsure of what their mission was when they first appeared, but they had stuff going on from the get-go. In addition to shooting documentary footage around the office and at conventions, their first major project was to make TV commercials for the Ultraverse Comics. This was a big deal. Malibu was the only comics publisher based in LA, which made them the only one with full access to filmmaking infrastructure. It wasn’t cheap, but it was a unique resource.

I hit it off with Darren and Ken right away, and they were always interested in getting up-close looks at the mechanics of making comics. This led to me “moonlighting” for Malibu Films as a storyboard artist. It was a whole new world for me, and I adapted to it instantly. In another three years, storyboarding would be my full time career. But that’s another story.

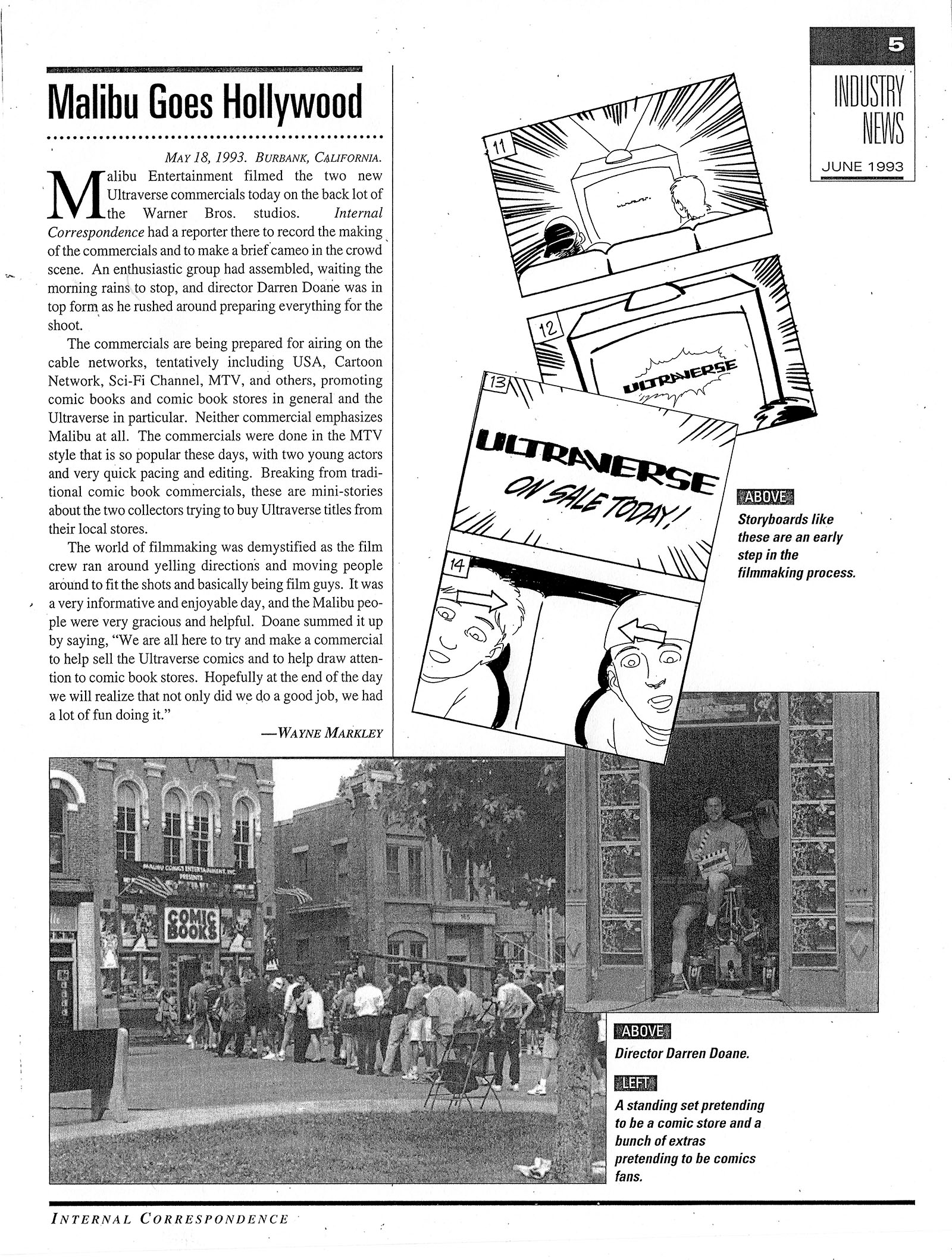

I drew a few boards for the first Ultraverse commercial. It was shot, edited, and broadcast. The store was a mockup at the WB backlot, and I designed the “COMIC BOOKS” sign that went over the door. A second commercial was shot inside the store, featuring EIC Chris Ulm as the store owner. A third, using the slogan “Jump on Now” came out later with a bungee-jumping motif.

See all three commercials on Youtube here.

I lettered both of the signs seen in the commercials

The part that made me giggle was that, for all the bluster and energy put into this effort, Malibu still had to piggyback on a classic anime program to get eyeballs. The first commercial made its debut on a late night broadcast of Speed Racer in May or June of 1993, probably because it was the best slot they could afford. The irony of it was exquisite. Not long before, we’d been working on a Speed Racer/Ninja High School crossover comic in the art department (helping to get it drawn in time) and our bellicose publisher Dave Olbrich marched in, saw it on our desks, and asked out loud, “Are we still publishing that bug-eyed Jap sh*t?”

Bruce Lewis and I locked eyes, trying to process the madness of what we’d just heard. Everything about it was surreal.

And yet, when a time slot was needed, they had to rely on Speed Racer.

All four issues of the crossover, co-published with NOW Comics. I penciled the last cover.

Two other projects tackled later that year by Malibu Films were a short teaser based on the character Hardcase and a half-hour film based on the character Firearm. I visited the set for a late-night shoot on Hardcase, and storyboarded a few scenes of the Firearm film. Hardcase was made to be shown at comic cons, sort of a teaser trailer for a movie that might get made someday. Firearm was released on VHS, bundled with a special edition comic book as a “sequel.” The tape was part 1, and the comic was part 2. That seemed like the wrong order to me, since the comic was sort of a step down, but the movie had some cameos by Malibu editors, so that was sort of fun.

The finished products can be seen on Youtube. (Hardcase here, Firearm here.)

Building #2, Westlake Village CA

Cart-Cart-Cart-Horse

When there’s a cloud hanging over your future, it’s kind of a good idea to keep an umbrella handy.

In 1993, Malibu moved a couple miles down the freeway to a bigger building. We’d been hearing about it since we got there, and when it finally came to pass we didn’t know how to feel about it. On one hand, there would be a lot more elbow room. We wouldn’t be jammed into the warehouse with four other departments. On the other hand, it felt like more building than we needed and rent must have cost a fortune. It was decorated to impress, with wonky architecture and huge, expensive printed murals of Ultraverse characters. The kind of building you’d set up to make yourself look like a Hollywood player. (Which, of course, Malibu was hoping to become.)

We’d seen the comics close up, and they weren’t terrible. Some were actually pretty good. But they were uneven. And not the sort of thing we would buy ourselves. Were we typical readers? Maybe not. Were we even the target audience? Maybe not. But then again, maybe we were. And if that was the case, we couldn’t see these comics generating enough business to pay for all this.

Some of the trading cards I drew. Get a better look at these and more here.

Also, it seemed like every day some new project was being added to the workload. They were already planning a set of trading cards before the first comics had been ordered. There would be CD-Rom editions of some first issues. (Remember, it was the early 90s.) Then there were the films I described above. Every new project came with a cost, and pushed the stakes ever higher. It was all founded on the idea of brand identity before they knew if the brand would be successful. They even gave us all stock options at one point, assuming that one day the company would be successful enough to go public and we’d each have a share. It was a nice gesture, but very premature. Too much was happening too early, and it made us queasy.

Our jobs depended on management keeping an umbrella handy. Yet, the closer we got to the Ultraverse launch, the fewer umbrellas we saw. Now you have some idea of the cloud that hung over us as the machine chugged forward. It got darker by the day as our faith eroded.

Anime comes to us

As I said above, there was little in the Ultraverse that would have interested me enough to buy it as a reader. But Malibu’s other imprints were still operating alongside it. As the resident anime experts on the staff, Bruce Lewis and I took a paternal interest in the Eternity line, which had passed into the hands of editor Mark Paniccia. When I made it clear that I wasn’t interested in drawing more Robotech Invid War comics after issue 18, Bruce stepped up and created Invid War Aftermath, which Mark was happy to accept. This was a big vote of confidence; Bruce’s writing and drawing style turned a hard corner away from every other Robotech comic, but Mark was willing to take the ride with him. It wouldn’t have happened if Bruce wasn’t there in house.

But this was just the start. Eternity opened other doors into the anime world. More than one import company came knocking to see about licensing comic book rights to Eternity, and it was my privilege to participate in some of those meetings. I got especially excited when a rep from Sunrise stopped by with a huge portfolio that included many of my favorite shows. That didn’t lead to anything, but he left behind some VHS promo tapes. One of those contained a horrific Gundam knockoff called Doozybots, which I shared with my anime pals at the next convention I went to. They shared it with their friends, and the virus caught hold. Yep, I was patient zero. I apologize for my actions.

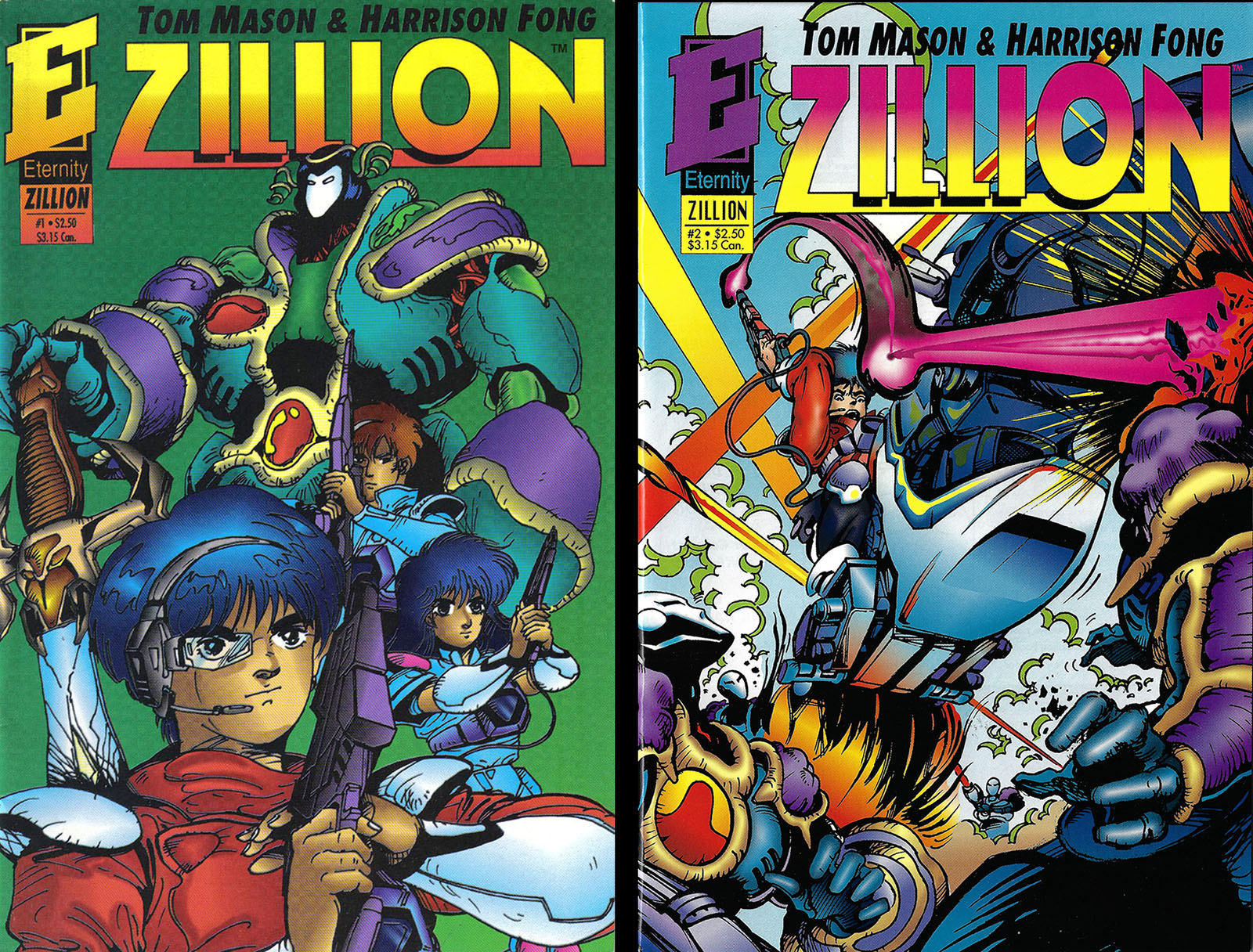

All four issues of Zillion; read them cover to cover farther down the page.

Streamline Pictures paid us a visit with the publishing rights to an anime series called Zillion. This one DID lead to something; Eternity published a 4-issue adaptation that passed through a few different hands. I lettered each issue. Harrison Fong, who I’d encountered on my very first professional comic (Mecha in 1988) drew the first three. When issue 2 came up short by six pages, I flexed my muscles and conscripted the entire art department to throw together a 6-page Zillion Guide using materials from my anime magazine collection. Mark Paniccia was grateful for the rescue, but it got me in trouble with EIC Chris Ulm, who saw it as insubordination. I didn’t care. It was fun to work on, didn’t interfere with anything else, and solved a problem Chris wasn’t even aware of. So screw him.

U.S. Manga Corps came calling with Project A-ko. This was a bigger deal than Zillion; a true fan-favorite anime film. The project originated with Ben Dunn at Antarctic Press, creator of Eternity’s Ninja High School. Ben wanted to draw A-ko, so he put together his own proposal for USMC. But he mistakenly mailed the proposal to Eternity instead (d’oh)! Now that Eternity was in the loop, Mark Paniccia ended up brokering the deal with USMC. I already had a working relationship with USMC president John O’Donnell, so I was asked to participate on the Eternity side. And just like that, I was laying out the pages for Ben Dunn to draw, which would be colored by Malibu. By issue 4, I was drawing it all myself. There’s much more to the Project A-ko story, so I’ll pick it up in a later article. But this was another lucky break that wouldn’t have come to pass if I wasn’t there on site.

Thumbnail and rough pencils for Orguss #1 (this was as far as it went)

There was almost one more chapter of this story. In 1992, US Renditions (the video arm of Books Nippan) started to release an English version of a very popular 1983 SF anime series called Super Dimension Century Orguss. Bruce and I knew it well, and when a deal was struck to turn it into an Eternity Comic, we were right there to throw our hats in the ring. We would share art duties to bring our individual strengths to the project. I plotted out an abridged adaption for 13 issues, since I didn’t think the market would support more than that. While the deal was being hammered out, we secretly started working on issue #0.

All this was done in anticipation of the project being approved. A contract had been signed and a licensing fee had been paid. We wanted to surprise everyone by having the first issue completely ready when the green light went on. Unfortunately, it never did. Despite all signs pointing to yes and Malibu actually promoting the series at a convention in October ’93, the deal collapsed and the project died. There was talk of it going to another publisher, but this never came to pass. I don’t know if an Orguss comic would have been a success, but I wish we’d at least gotten the chance to find out.

(At right: unused promotional image, done on spec.)

There had also been a point prior to all this, before I joined the staff, when I thought Eternity should go after its first manga from Japan. I picked a title I thought would do well for them, got the first chapter translated on my own, lettered it as a sample, and sent it in. Basically, I created a complete first issue as a pitch. They looked at it, shrugged, and said no thanks. They didn’t think it would go anywhere. The name of that manga was Dragonball.

I swear to Gob, if Eternity had picked up Dragonball back then, it would have carried that bloody company through all the turmoil they were about to endure and they might still be around today. But… “No thanks.”

Then there was the big one. On an otherwise average day, I was called over to visit the guy in charge of licensing. He handed me a letter he’d gotten from a company called Voyager Entertainment, based in New Jersey. In this letter, they introduced themselves as the English-language rights holder for a famous anime series. The guy didn’t know much about it and wanted to get my input. I stared at the title on the letter. My mouth hung open as my eyes locked on those letters.

Star Blazers.

Holy freakin’ moly. Star Blazers was knocking on the door.

I told him absolutely YES Eternity should pick this up, and Bruce and I would draw it. When I told Bruce afterward, he practically hit the ceiling. This was our reward for putting up with all the stupidity. Our dream project had literally been delivered to our doorstep.

Long story short (yeah, I know, too late): Eternity didn’t get Star Blazers. But Bruce and I weren’t about to let it slip through our fingers. We were sufficiently motivated to take steps that would literally change our lives. Click here to see what happened next.

And he taketh away

Above I described the Orguss comic series that came so tantilizingly close. During my tenure at Malibu, a few other things also nearly happened that would have been very nice career boosters if fate didn’t kill them in the crib.

In 1993/94 Harvey Comics caused a stir when they published 8 issues of an Ultraman comic book series before going bankrupt and closing down after over 50 years of publishing. Despite Harvey’s sorry fate, their Ultracomics did pretty well, and one of the crafty Malibu editors came up with an idea to jump on the bandwagon. Around the same time, Malibu had the license to Gigantor, and made it the focal point of an anthology title called Eternity Triple Action. (Which included my original strip Armored Road Police.)

The idea was…CROSSOVER! What if Malibu teamed up with Harvey to get these two giants into a single story? Since I was the resident anime/manga guy, they asked me to create a piece to pitch the idea to Harvey. Ultimately, it went nowhere. I’m guessing Harvey was in the weeds by that time and wasn’t able to commit. But I still got to draw the characters together, maybe for the first time in history.

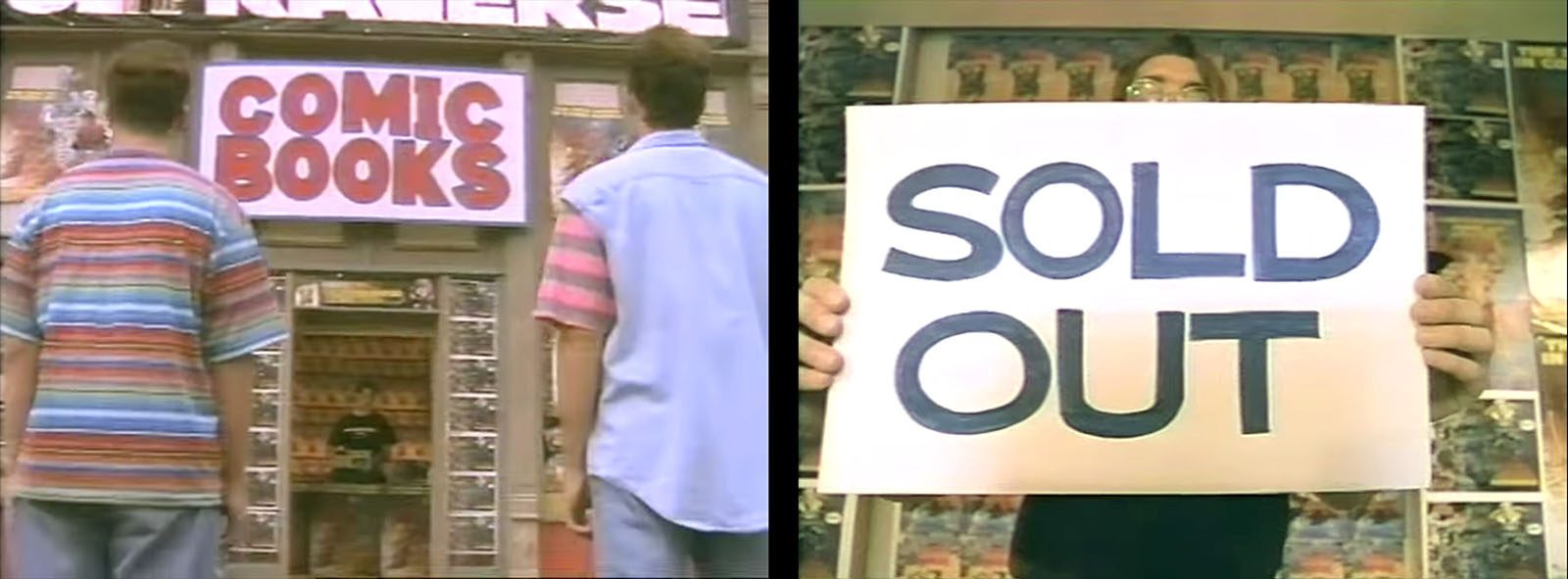

Malibu successfully licensed Street Fighter from Capcom and got three issues published in the summer of ’93, but Capcom wasn’t happy with the art. Either it wasn’t up to their standards or it was simply too “American.” With the deal on the verge of being dropped, an editor came to me and asked if I could use my “manga style” influence to come up with a couple tryout pieces that would get Capcom to reconsider. If it worked out, I’d probably end up drawing the comic. Which sounded pretty cool.

I pulled some reference from a Street Fighter art book, but my main inspiration was the Fist of the North Star manga, which I adored. Since Street Fighter itself began as a pastiche of FotNS, I thought applying that style would be a slam dunk. I signaled this directly with my signatures, “Timshiro” and “Tim of the North Star,” in Japanese. The Malibu editor was happy with the results, and they went through the color department to get star treatment for a Hail Mary pitch to Capcom. You’ve probably figured out that this was not enough to save the project. But it was a lot of fun drawing them.

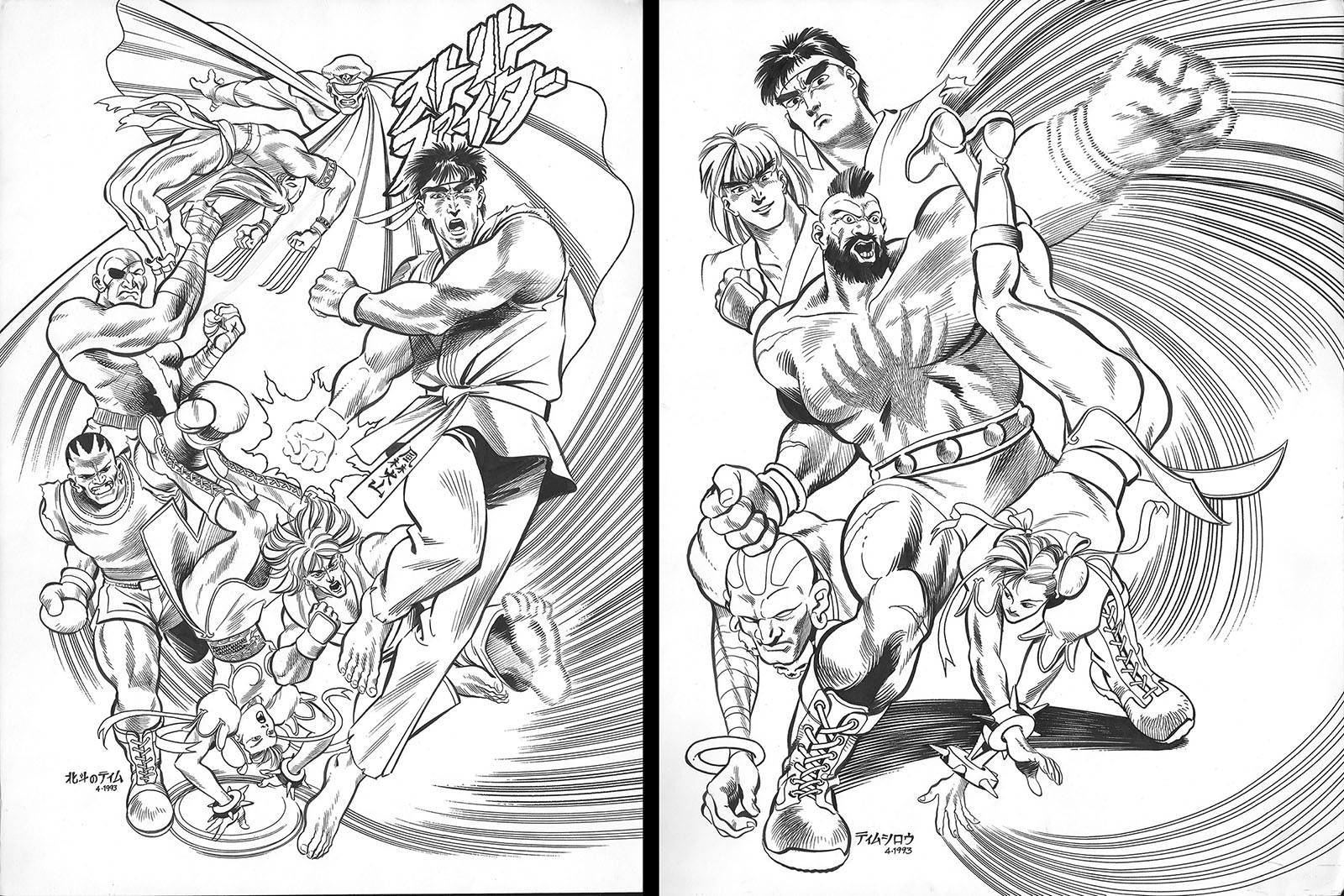

Street Fighter couldn’t be saved, so Malibu’s next move was to go after its closest imitator, Mortal Kombat. They came to me again for pitch art and I channeled the same influences for these two pieces. This time it worked, and they landed the license, but I was passed over as the artist. Someone at Midway preferred the look of someone else’s samples, since they “looked more like the hot new Image Comics style.” (You can imagine the temperature of my blood when I heard about that.) 26 issues were published in ’94 and ’95 but they were ultimately canceled when sales dropped.

Click here for a better look at the art above.

Pushing my way in

By mid 1993, the freelance projects that had kept me going since my first Malibu assignment (Lensman in 1989) finally ran dry. Return to Macross, Captain Harlock, and Armored Road Police all came to an end just as the Ultraverse launched in June, and I needed something to replace that income. (I was working full time, but that was only a living wage, not a thriving wage.) The three other projects I mentioned above also fell apart.

Therefore, I set my sights on the logical target: an Ultraverse comic. Not all the artists in the first string were cut out for a monthly assignment; as they dropped off the roster, opportunities opened up. This led to a battle of wills. EIC Chris Ulm saw me as a “manga-style” artist rather than a superhero artist. But I saw a lot of not-very-good superhero art coming through the door and knew I could do better. When all the other prospects dried up, I asked Chris, “If I submit an Ultraverse sample that you like, do I have a hope in hell of getting work in the line?” He gave me a qualified yes.

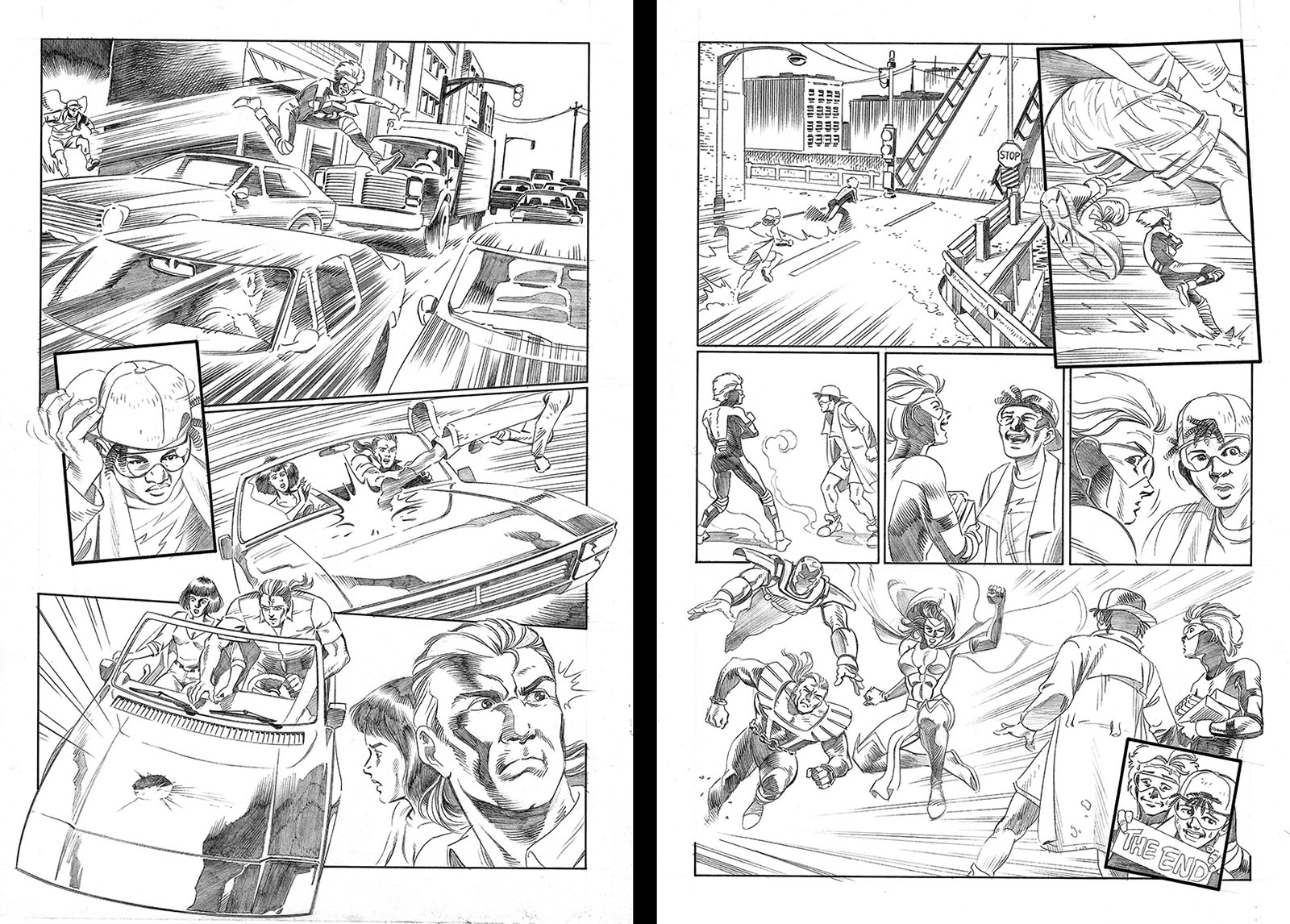

Chris didn’t want “manga style,” so I had to avoid that. But I’d learned that this was really code for “character design.” The big eyes and such. But Dynamic storytelling – flow and movement – is really what manga offers, and I could do that for sure. (In another ten years or so, everyone would be doing it that way.) To hit this as hard as possible, I created a 6-page sample story (on my own time) that played entirely without words. The plot was simple; two speedster characters bump into each other and decide to race. They slam through the city, encountering a few other characters along the way.

I put all my creative energy into this sample, finished it over a few days, and showed it around the office. Everyone LOVED it, especially all the fine touches. Darren Doane in the film department was particularly impressed. He analyzed it as a filmmaker, recognizing all the techniques I brought to bear, and showered it with praise. I showed it to one of the Ultraverse writers who visited us one day, and he said he wanted to write a script for it. Everything looked promising. And then presentation time came.

The first thing Chris said was that it contained some of the best storytelling he’d ever seen, and that this is what he always admired most about my work. Good start. But then the spell was broken.

“I’m still seeing some manga style here.”

I asked him to clarify.

“Well, some of the eyes are a little large…”

Bloody hell. This is the moment I knew reality wasn’t a factor any more. I was dealing with someone who couldn’t see past his own bias. I’d already been losing respect for him at a steady pace due to his increasingly shaky decisions, and this didn’t help. As the head of the art department, I saw every single page that came in from freelancers, and in my view some of it was just plain incompetent. When I made that case to him, these words actually came out of his mouth in response: “Tim, your problem is that you’re still using words like competent.”

(“I sure wish you would” was the obvious rejoinder, but I held my tongue.)

We’d started out as allies when he first gave me a shot in 1989, and I never let him down. I beat every deadline and my work steadily improved month by month. “Competent” was my credo. It’s what got me the offer to move across the country and take the job running the art department. And now it was being held against me. While I felt the room spinning, more words came out of his face hole. What he wanted – i.e., what he assumed readers wanted – was something “Completely NUTS.” (Direct quote) To sum it up: I turned in a sample that everyone liked, but it was COMPETENT instead of NUTS. And therefore, it was turned down.

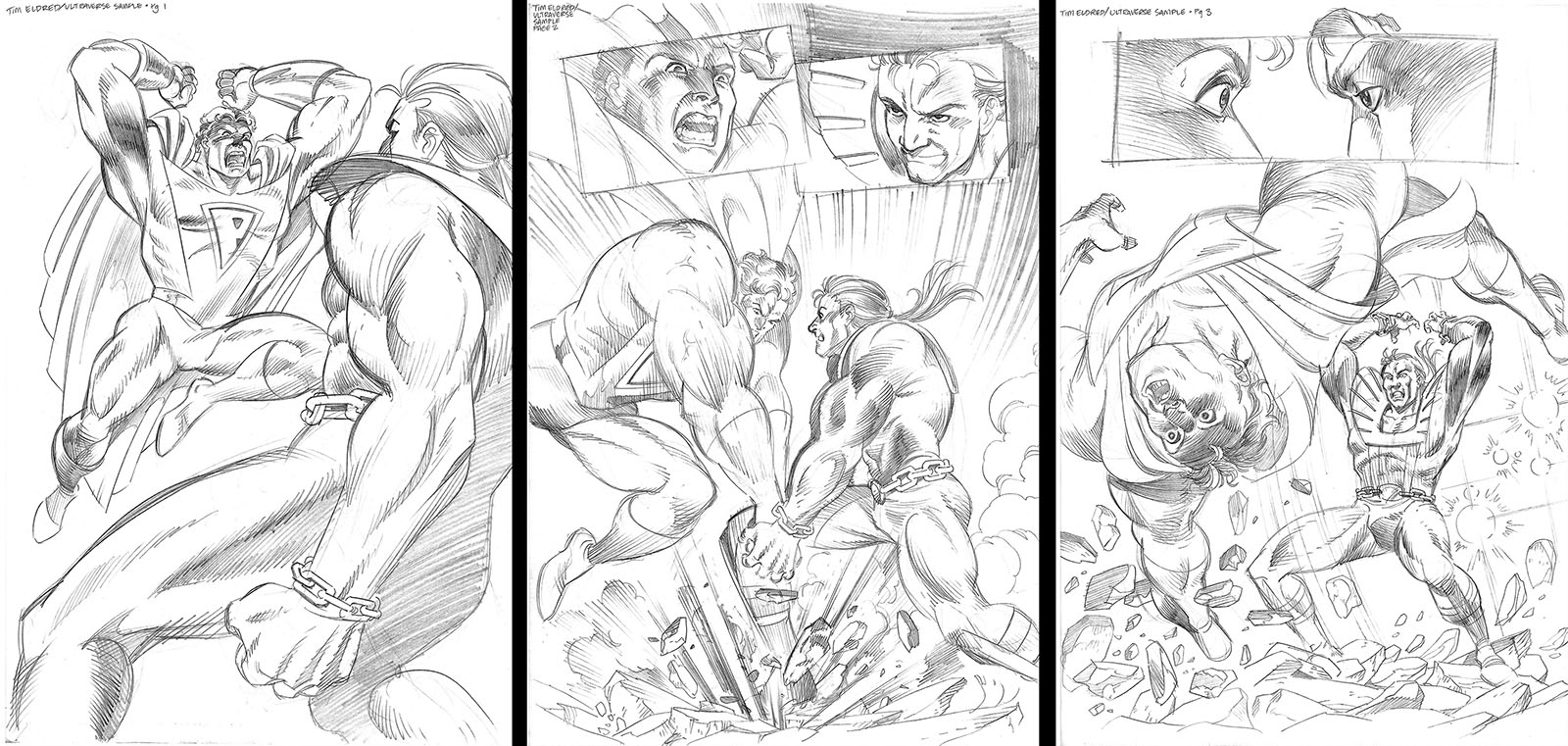

Just when I thought he was about to slam the door on this, he asked me to produce another sample. Something much simpler this time, featuring only two characters. Something thrown together with none of my usual meticulous planning or structure. Like that “hot new Image style.” I went away and got started. it took all of two hours and virtually no brainpower. You couldn’t get more “Image style” than that.

When I showed this sample around the office, the general reaction was, “Oh. Okay. Well, I guess that’s what Chris wants.” A few days later, I got Ulm’s attention again, showed him the pages, and he had no further complaints. They were exactly what he wanted to see. In a matter of days, I had my first Ultraverse assignment. Was it penciling a comic? Nope. I would be inking one instead: The Strangers, drawn by Rick Hoberg. Absolutely none of the skills I demonstrated in my sample were required. And Rick’s style wasn’t “NUTS” by any definition. If anything, it was even more meticulous than mine. This wasn’t the result I wanted, but it lasted a year and paid some bills.

Mostly, this struggle revealed something I’d always suspected: when given a choice, readers preferred smart comics to dumb ones. They just usually weren’t given a choice. The dumb ones were easier to make, so they outnumbered the smart ones. Editors defended their choices by saying, “People must like it, or they wouldn’t buy it.” But there was a huge blind spot in that argument; by and large, people weren’t buying comics. Readership was in freefall. The public was making a choice. Later in 1993, that fact was going to slam down onto the pointy heads of everyone who had ignored reality for too long.

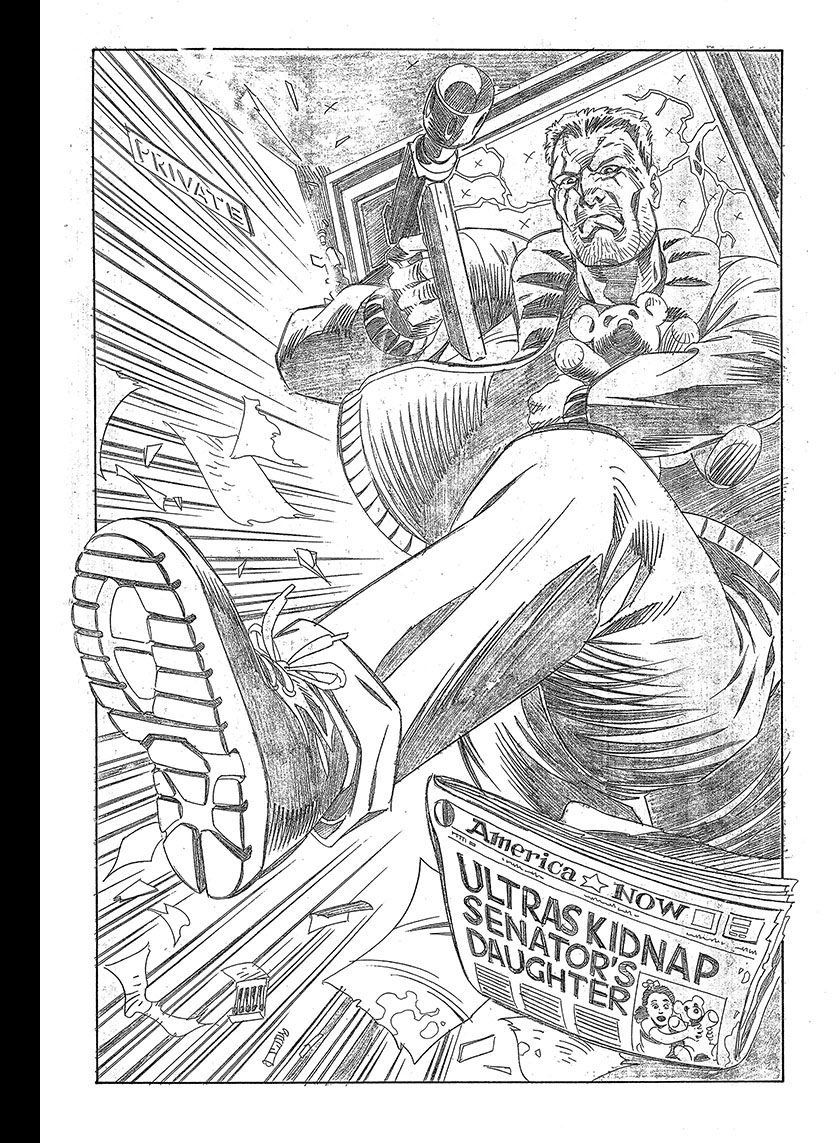

I did one more Ultraverse tryout piece, this time focused on Firearm. He was the single non-super-powered character in the pantheon, and I was the regular letterer on the comic. It was the only one I might have bought if I weren’t working on it. I did a pinup image to see where it could take me. It turned out to be a good move; it earned me a fill-in issue when the regular penciller couldn’t finish on time. (See it in part 1.)

Click here for a better look at the art above.

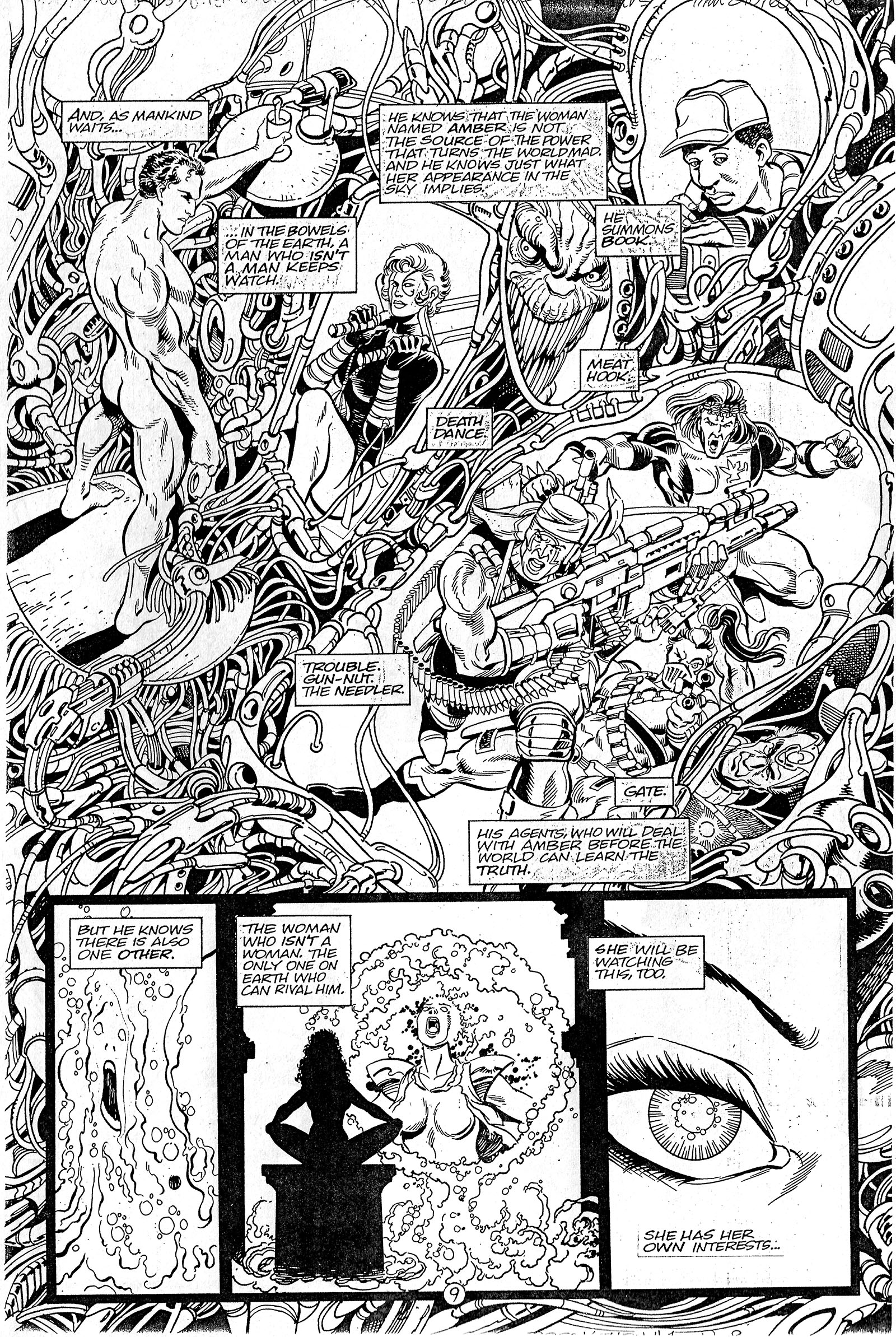

Another assignment came up later in the summer, sort of by accident. I was lettering a comic called Break-Thru, which was to be the year-end “special event.” It was a 2-issue mega-crossover featuring all the Ultraverse characters in a huge interdimensional dust-up. It would be published in December, just six months after the line first appeared. (Cart-cart-cart-horse.) It was penciled by industry legend George Perez, and it was stunning to see his work directly in front of me. Incidentally, George’s work was also about as far from “NUTS” as you could get.

It was also heartbreaking to see what the inker was doing to it. Perez’ work was always highly detailed and very intricate, and needed an exceptional inker to preserve it. The first guy they hired was not exceptional, and all the money they were spending on George Perez was being squandered. The company’s unspoken rule was that if you brought a problem to the table, you also had to offer a solution (a respectable policy), so that’s what I did. I went to Chris Ulm and Hank Kanalz (co-editors on the book) and showed them what I was seeing. And then I offered to take over the inking.

This was me being a good soldier, helping them out of a bind, but they assumed I was trying to grab some glory for myself on a high-profile book. This was not said to me directly, but got back to me second hand. Nevertheless, they admitted I was right and put me to work as an “assistant inker” while they got someone else for the second issue. It was a humbling experience inking George Perez (see samples farther down the page). He and I had the same birthday, which made me feel a sort of kinship. I never met the guy, but at least one day out of the year I knew what was on his mind.

However, after all this back and forth, the damage was done between me and Chris Ulm. My respect for him had eroded for good. I would never again offer to solve his problems.

Coming in part 3: Escape from Comicpocalypse!

Zillion #1

Zillion #2

Zillion #3

Zillion #4

Sample pages from Break-Thru #1

I kept copies of two pages for comparison. The first version of each was by inked by the original candidate. The second version is mine.

See the finished comic here