Mummies Alive, 1996

When I embarked on my TV cartoon career, it didn’t occur to me that one of the privileges of a long resume is the freedom to completely forget something you worked on. No project is unforgettable at the time; it consumes your entire creative bandwidth and demands all the energy you can muster. The money it earns you is often a critical bulwark against financial disaster. But, if you’re very lucky, you can look back at that project years later and say, “Oh yeah, that thing.”

That’s where this crazy series fits into my narrative. It was the one and only storyboard I ever drew for DIC (a company I sort of dreaded back in the day) between two of my most important career steps: Wing Commander Academy (my first series) and Extreme Ghostbusters (which made me a director). It landed on me in the fall of 1996, when it was unclear if I would continue in TV or go back to comics. I had no idea which way the pendulum would swing, and this show would not end up being a deciding factor. But it fits into an interesting inflection point, and I hope I’m enough of a wordsmith to do it justice.

First, an overview of the show itself: a gang of Egyptian mummies is revived in the modern world to protect the 12-year-old descendant of their pharaoh from an evil sorcerer on a quest for immortality. Rather than stumbling around as dried-up zombie husks, they draw power from Egyptian gods that turns them superhuman guardians against villains and evil spirits. Its mix of superpowers and mythology was clearly inspired by Gargoyles (not surprising, since that’s where the writers came from), and it went much farther than you might think with a 42-episode syndication package that made its debut in September 1997. Toys were produced and a few home videos were released, but ratings didn’t support more episodes. (Incidentally, there was a 2015 documentary series with the same title, but the two are unrelated.)

Roughly a year before the debut, I was hired to storyboard part of the fifth episode, titled Desert Chic. I met with Producer/Director Seth Kearsley, unaware that it was his first time in that position. (He was also 8 years younger than me, but had much more experience). He gave me a crash course in what the show was about, demonstrating that the most important skill for longevity in this game is adaptibility. You aren’t given a lot of time for homework, so you must be flexible enough to take in basic story info and then dive in like you live there. After a few years of making comic books and RPG art, I had developed this skill already. And anyway, part of a director’s job is to fill you in as you go. You just need to give them something solid to build on.

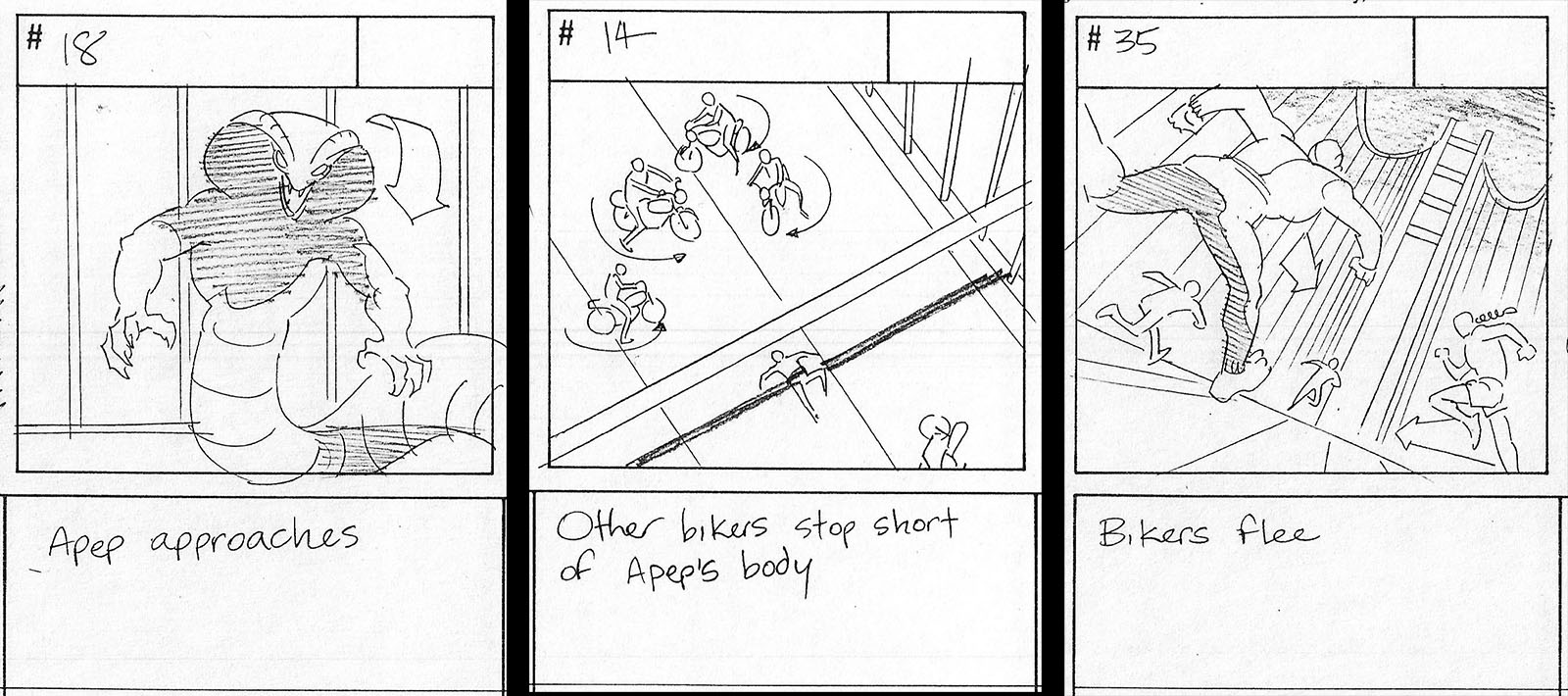

When you’re given a script to work from, it comes with model sheets for drawing reference and two levels of story input: the basic premise (what I described above) and the specifics of your episode. Just enough to get your teeth into it without being overwhelmed with details. For Episode 5, the specifics were that a gang of Egyptian demons possesses a gang of bikers and has a street chase against one of the mummy characters before teaming up with the main villain of the show. All this took place in Act 1 of the script. (Back in the broadcast days, all scripts were broken up into three acts around commercial breaks. In the streaming world, that’s no longer a requirement.)

I took it home, drew my rough version, and brought it back to Seth for review. I don’t remember how many revision notes he gave me, but when I look at the board now it seems mostly in line with my storytelling style. When I compare it to the finished episode, the shots are mostly intact, but about 30% were revised. I wasn’t invited back for a second assignment, so that tells me 30% was above the acceptable threshold. No matter. There would soon be ghosts in need of busting.

What truly stands out to me when I look back at this storyboard is how much information I was able to leave out compared with what’s expected today. Some shots contain just one panel, as if you’re looking at a comic book. That’s where my illustration experience paid off, since I knew which single image to draw as an anchor. And the finished footage has all the action exactly as I imagined it, so it worked out OK. But it’s not how we do things today. Why? The one word answer is: ANIMATICS.

If you don’t know what that is, you can see some simple examples here. They are essentially a slideshow that combines storyboard drawings with voice recordings into the blueprint of an episode. The drawings are timed to match words or actions and give you an impression of how the finished show will look. Seeing them in this form can reveal problems you don’t see on paper, and also show you where the gaps are.

Just as computers revolutionized special effects for movies, they also revolutionized the way TV cartoons are made. That revolution was happening right around the time my career got started in 1996. Desktop computers were becoming just powerful enough to combine images and sound using an editing app called Adobe Premiere. It was agonizingly slow and clunky by today’s standards, but back then it was cutting edge and dazzling. As with every digital breakthrough, it made some things easier while it made other things harder.

Before this tool was available, cartoons relied heavily on people with the job titles of “slugger” and “timer.” A “slugger” would go through a storyboard and decide about how much screen time a specific panel would represent. A timer would then expand on that information, deciding how many frames specific actions would cover: footsteps, head turns, eye blinks, etc. All of that mathematic alchemy would end up on an Exposure Sheet (“X-sheet”). As musicians read a score, Animators read X-sheets. It tells them how many individual cels to draw, how those cels should be layered, and how long the scenes should be. Writing X-sheets is a highly specialized craft that goes all the way back to the beginning of animation.

When animatics became part of the workflow, they took a lot of the guesswork out of the process. Now you could do the work of a slugger simply by putting a storyboard on your screen for a certain number of frames and then adjusting it to be longer or shorter. A timer could take it from there. And if you added more drawings to a scene, you could do some of the work of a timer as well. They still needed to generate an X-sheet, but you had much more control over the information that would end up on it. You also had a way to find out if your episode was the correct length and make cuts before it got into the timing phase. All of these factors made production easier.

On the other hand, you could no longer get away with a minimal storyboard, like the one I drew for Mummies Alive. You couldn’t just put up a single drawing and have it represent an entire scene. Take these, for example:

They show what’s happening in a scene, but there’s a lot left out. You don’t know what the first frame and last frame look like. An old-school slugger and timer could infer it from a single drawing, but animatics were “new school.” They were presentation tools that you showed to a client who probably didn’t know how to interpret a paper storyboard. For their sake, you had to include more drawings. The more you drew, the clearer the show became for them. You can probably guess what this led to.

Almost overnight, drawing demands skyrocketed. Rather than the show itself, animatics turned into the end product for us, and we had to make them look as good as possible. Storyboarding became less like comic books and more like animation, where all the key poses are worked out in detail. Predictably, production slowed down and cost went up, since more artists were needed to meet the workload. Animatics were the singular reason for the enormous size of the Extreme Ghostbusters crew, over 100 people. I was only told afterward that the show came dangerously close to crashing its own budget. Careers were made and lost because of animatics.

My first two TV shows, Wing Commander Academy and Mummies Alive, both took place in the last days of the pre-animatic world. For that brief time in 1996, I got away with drawing the minimum. I’m very grateful now that I had that experience when I did, because it set me up to fully appreciate the rollercoaster ride that followed.

Today, animatics are still the measure of our efforts. They’re much easier to make on a technical level; thanks to an app called Storyboard Pro, we can do in just a few hours what used to take days in Adobe Premiere. But the drawing demands have only increased as a result. As I write these words, I just finished a stint on a forthcoming prime time Fox comedy series (called Grimsburg) that came as close to full animation as I ever want to get. In addition, the craft of slugging is extinct and timing is on life support. On CG productions, for example, animatics make X-sheets irrelevant. Now an animator can just build a finished film on top of an animatic and match the timing visually. Traditional sheet timers can only get work on 2D shows, and most of the decisions are already made for them.

But on balance, I think we’re about where we always were. It’s still a complex, highly-specialized profession. It consumes your entire creative bandwidth and demands all the energy you can muster. The money it earns you is often a critical bulwark against financial disaster. But, if you’re very lucky, you can look back at a project years later and say, “Oh yeah, that thing.”

Read more about Mummies Alive on Wikipedia here

See all the episodes on Youtube here

See Seth Kearsley’s 25th anniversary lookback here