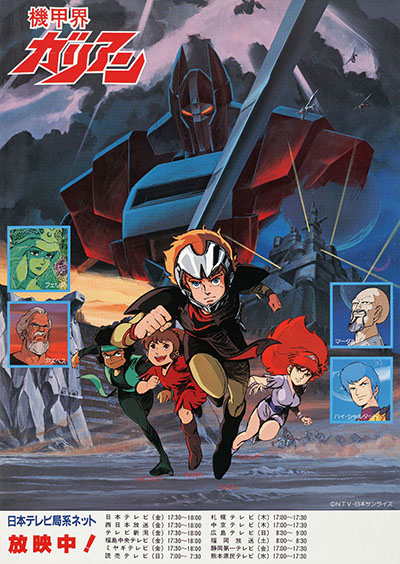

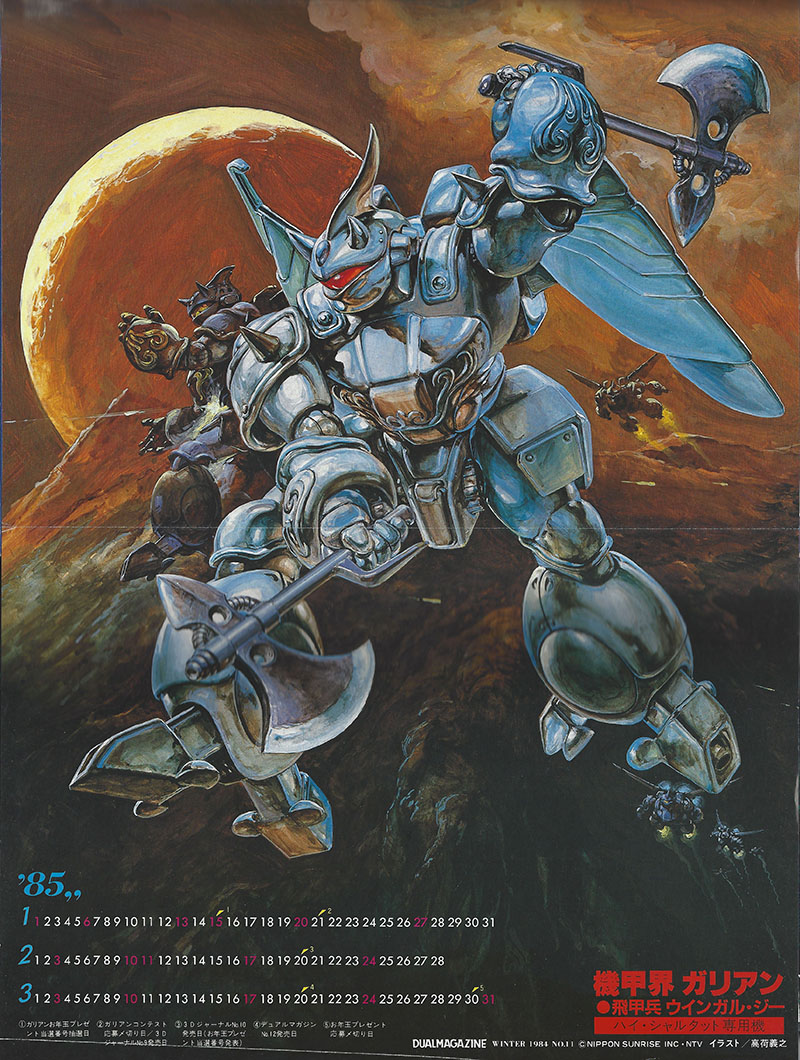

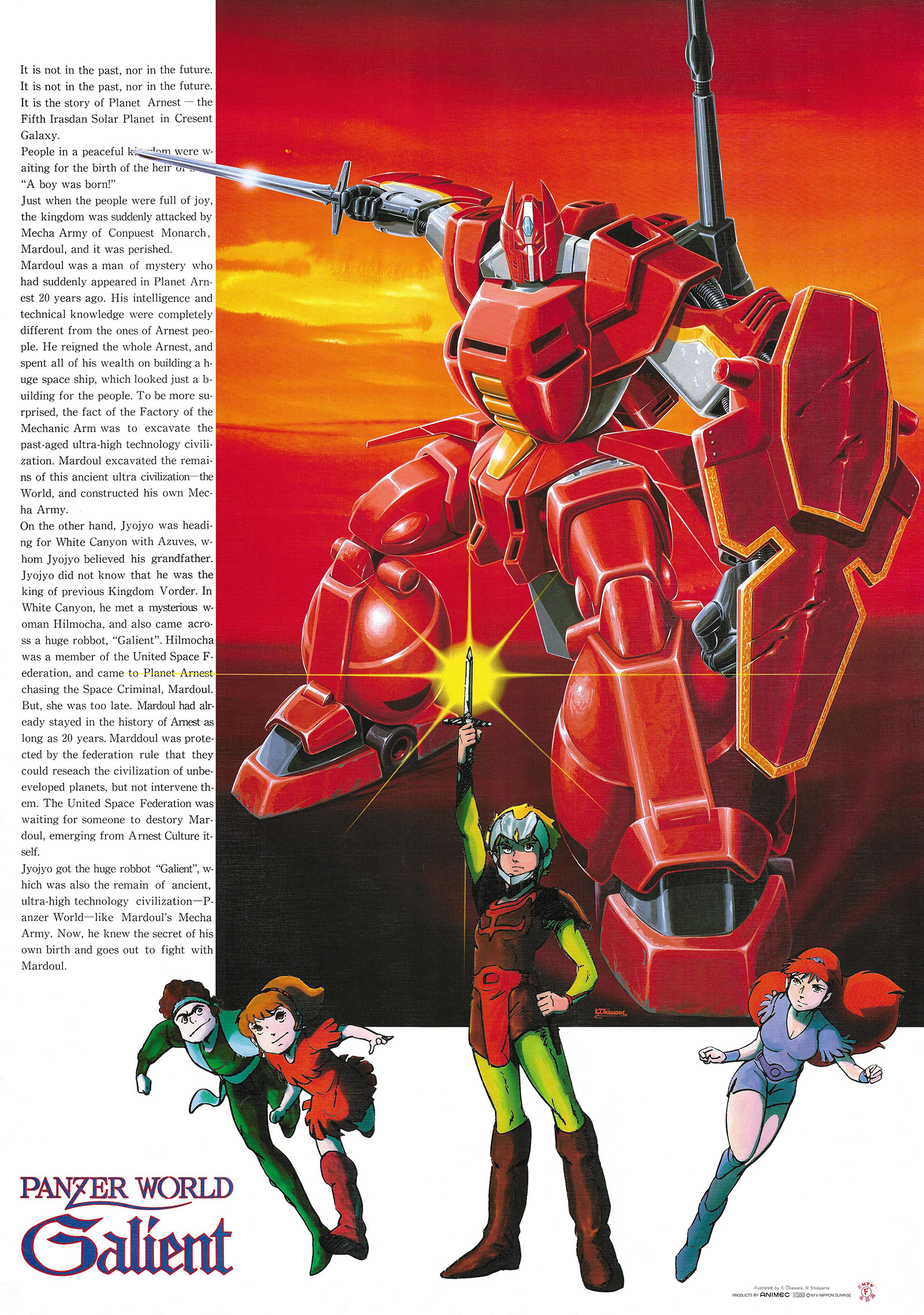

Series profile: Panzer World Galient, 1984

If, like me, you got into anime in the early-to-mid 80s and started collecting shows on VHS (the only available media) you were right on time for the Real Robot explosion. Mainly ushered in by Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) it marked a transition from the Super Robot genre of the 70s. The term refers to a paradigm shift toward realism in mecha design, but it coincided with a move toward more mature and complex characterization as well. The precondition for this was a maturing of anime itself in the late 70s that made it acceptable for older audiences. With money. Which made a lot of new things possible.

The story in Gundam dispensed with magical thinking that had powered the Super Robots, reducing its mecha’s stature to stylized vehicles that could be mass-produced. Regular people could pilot them, which opened up whole new storytelling opportunities. Two directors stood out in this period as industry leaders, creating one show after another: Yoshiyuki Tomino and Ryosuke Takahashi. Both had climbed the Super Robot ladder, and both were ready to remake the genre when they reached positions of influence.

Tomino started with Gundam and carried on for years with one innovative program after another. Takahashi Started with a rival series, Fang of the Sun Dougram (1981), and did the same. Whereas Gundam was set in space, Dougram stuck to the ground. Both offered gritty stories of war and politics, but Dougram got deeper into the dirt and put stronger emphasis on the “real” part of “Real Robot.”

Takahashi’s second series, Armored Trooper Votoms, went even farther. This time, the robots were stripped down to the point of being disposable. Their design was so hardcore they looked as if they could be stamped out of a factory on our world right now. (Votoms is my all-time favorite mecha anime and will be covered at length in other articles, so stay tuned.)

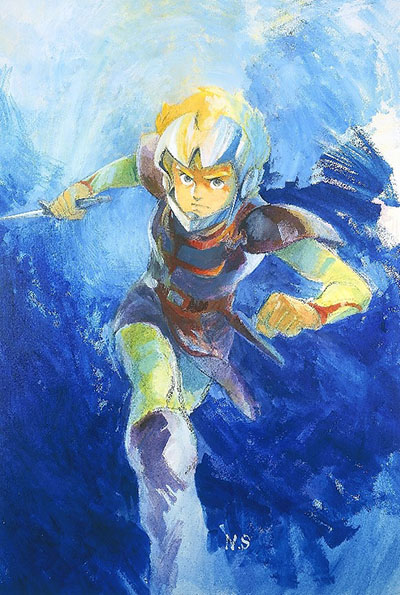

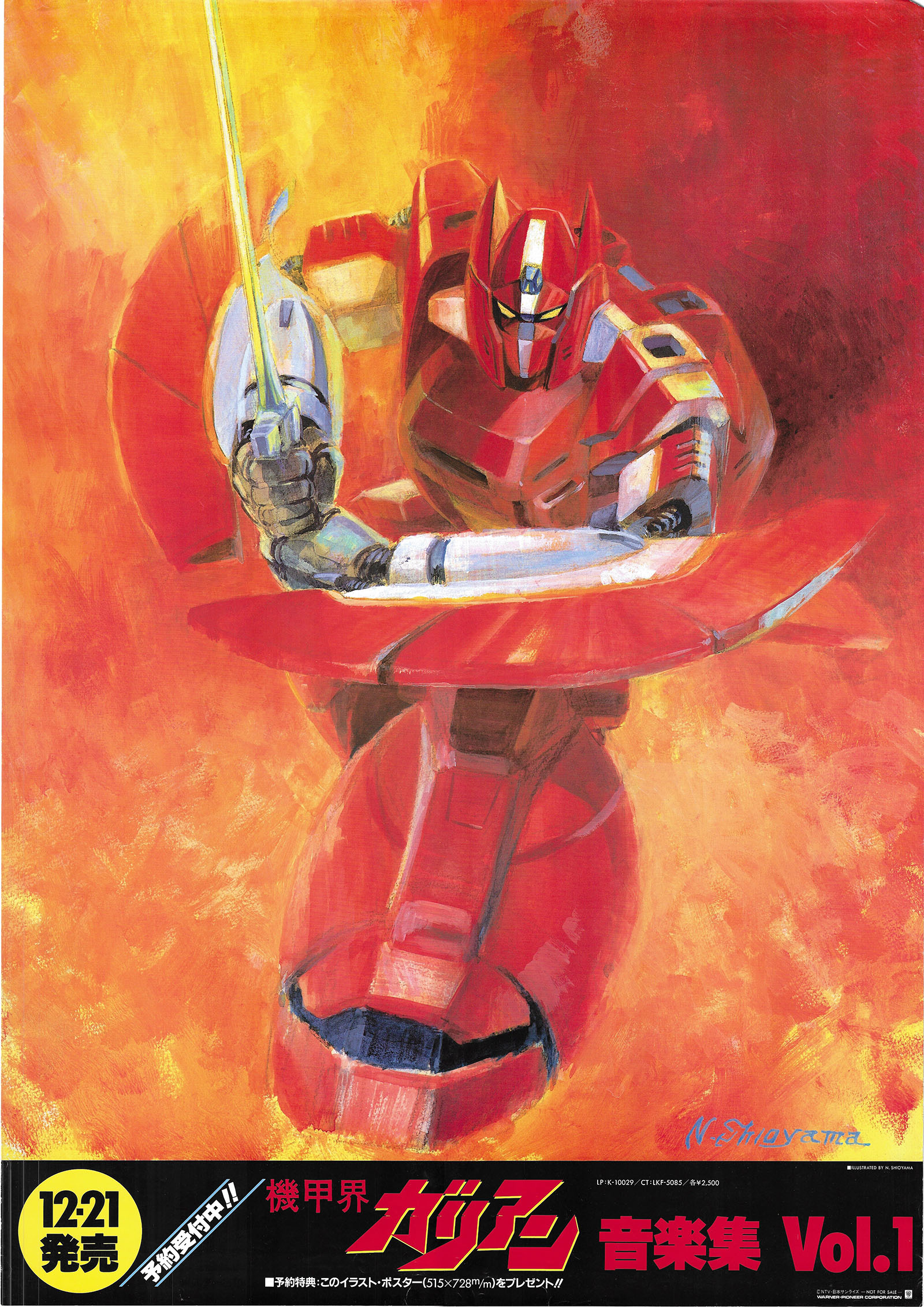

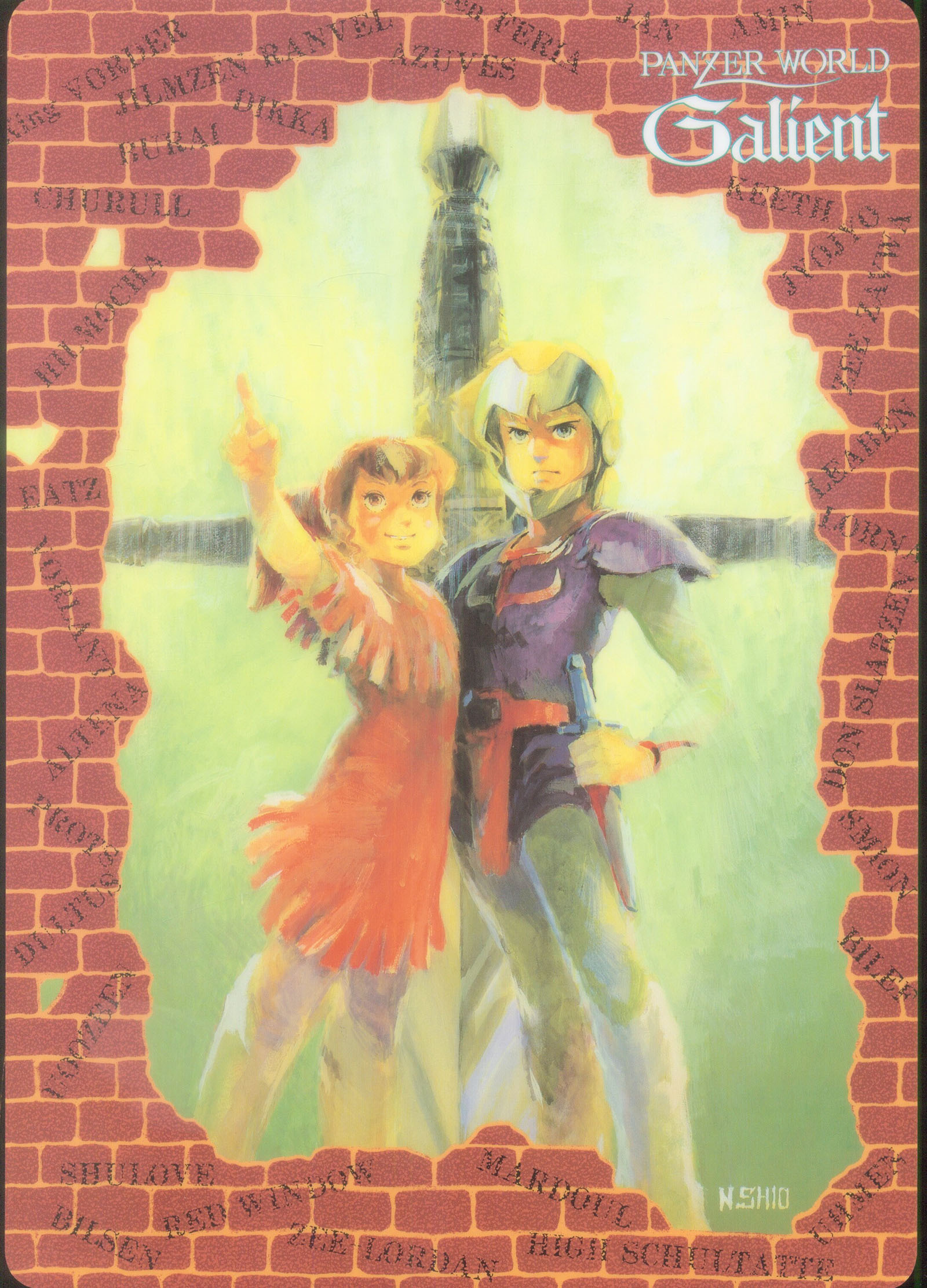

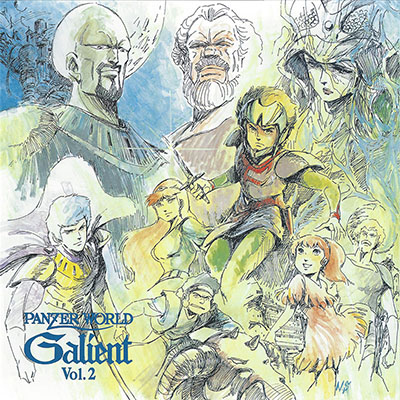

Art by Character Designer Norio Shioyama

As Votoms approached its climax in 1984 and Takahashi was asked to start on his next series, he was ready to push the Real Robot genre in a new direction: high fantasy. Thus began the development of Panzer World Galient.

In a way, the title of the show itself was a signal of change. By this time, there was a well-established trend of titling shows after their lead mecha, splitting it into class and name. It started with Mobile Suit Gundam. The mecha were classified as Mobile Suits and the main one was named Gundam. All of Tomino’s subsequent shows followed the formula: Aura Battler Dunbine, Heavy Metal L-Gaim, etc.

Takahashi played with variations on this. “Fang of the Sun” wasn’t a class of mecha, but it was the battlefield nickname for the group that supported Dougram. “Armored Trooper” was a class of mecha, but “Votoms” was an extension of the term rather than a specific model (sort of like “sports utility vehicles”). In Panzer World Galient, the mecha class was “Panzer” and the lead mecha was named “Galient” (pronounced “Garian” in Japanese), but “world” broadened the concept into a world of Panzers with Galient as the main one. That title was appropriate, since the world-building played a huge role in the storytelling.

Incidentally, the naming convention for the Real Robot genre tended to magnify skepticism among those who distrusted anime for their own particular reasons. “How could anyone be interested in a story about a robot?” Well, the stories were never “about” the robots. The robots functioned as unifiers for the human characters who gathered around them. The stories were always about those humans and how they chose to wield power.

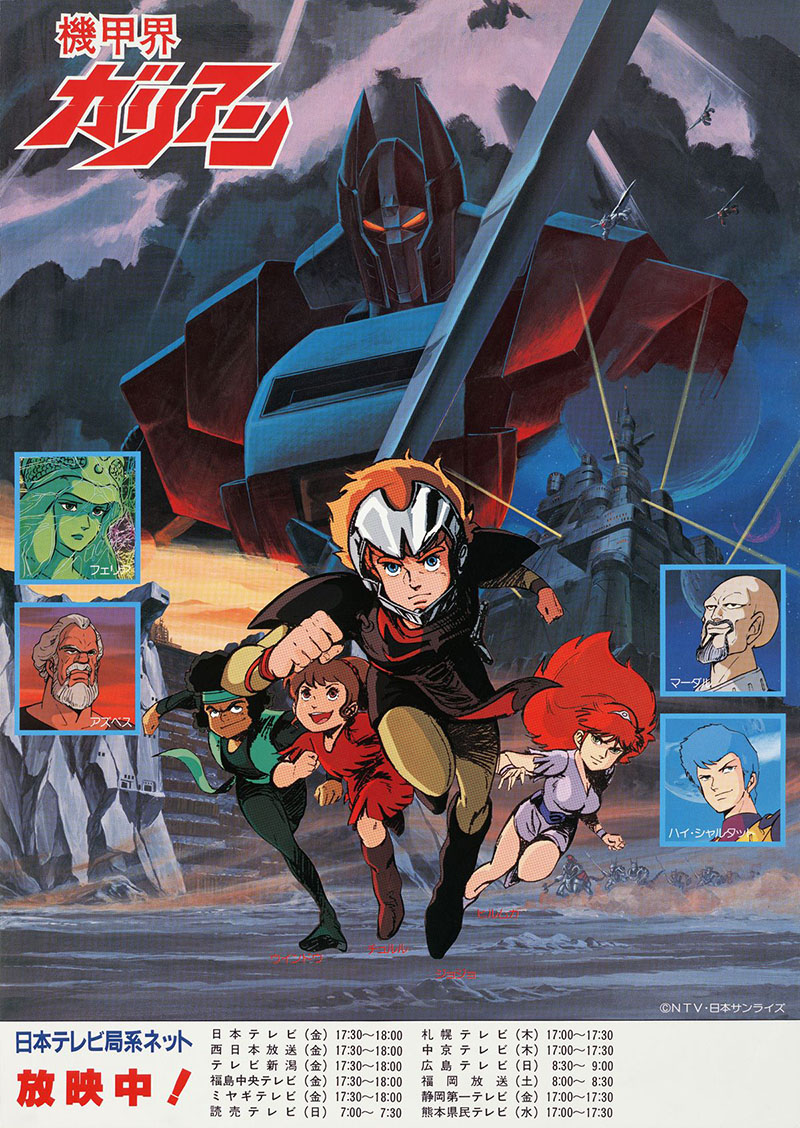

Galient made its broadcast debut in October 1984 and ran for 25 episodes. This was half the length of Votoms and only a third the length of Dougram. It was originally intended to run for a full year, but ratings weren’t as high as the primary sponsor had hoped. That sponsor was Takara, the toy and model company that backed all of Takahashi’s anime. They always ran second to Bandai, the sponsor of Tomino’s shows. Despite the disappointing ratings, Takara had some fantastic mecha designs to market and equally fantastic art to promote them. (More about that can be found elsewhere in this profile.)

Takara’s decision to reduce the length came in the second half, forcing the writers to condense the climax. This sounds like a recipe for disaster, but in the end it kept the pacing brisk and prevented “filler creep” from compromising what was already a tightly-written story that moved decisively forward with every episode.

That story begins on the medieval planet Arst in the distant Crescent Galaxy where a prince is born into a royal family. Within moments, an enemy force of giant centaur-style mecha invades and takes over the kingdom. The king is killed and the queen is captured as the captain of the guard (named Azbes) escapes into the wilderness with the baby boy. Twelve years later, Prince Jordy Vorder has grown into a strapping young lad with no knowledge of his heritage. Asves has renamed him Jojo and waits for the day when control of the kingdom can be wrested back from the evil lord Mardar and his mecha army.

Just to give you some idea of how fast the show moves, I’ve only described part of Episode 1. From there, a huge story unfolds that demonstrates (A) what Lord of the Rings might have been like with giant robots instead of Orcs and Nazgul, and (B) why Star Trek‘s Federation takes the Prime Directive so seriously. In Galient, Mardar has violated such a directive on a planetary scale, and their version of the Federation has to decide what to do about it.

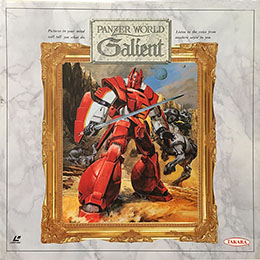

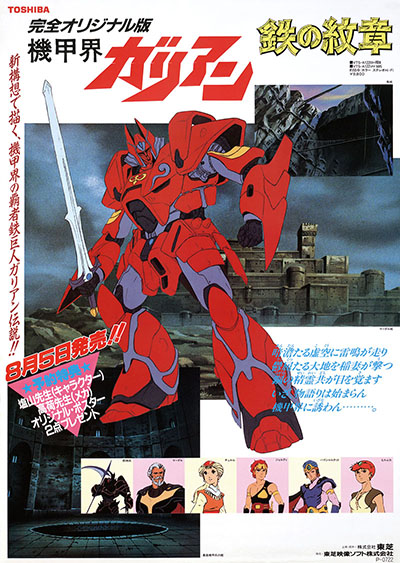

Promotion for the Crest of Iron OAV

In other anime, the mecha is a contemporary invention. In Galient, it’s ancient; abandoned superweapons of a much older civilization that are excavated from the ground and put to use in medieval warfare. The lead mecha is the most powerful by far, destined for use by Jojo in the struggle against Mardar. It can transform and uses an innovative weapon called the Panzer Blade, a sword that extends into a slicing whip. Takahashi is said to have gotten the idea from a bicycle chain, and many versions of it later turned up elsewhere, including in Pacific Rim.

As the story progresses, the layers of Mardar’s overall plan are peeled back and he is revealed as a far more complex character than expected. He is sadistic and ruthless, but the true enemy lies far beyond Arst and is driven by the cruelest impulse of all: apathy.

I discovered Galient after first getting hooked on Armored Trooper Votoms, drawn in by the design aesthetic and directorial style. It was no accident, since the show inherited the same production team: Director Ryosuke Takahashi, Writers Jinzo Toriumi and Soji Yoshikawa, Character Designer Norio Shioyama, and Mecha Designer Kunio Okawara. It felt smoother, more confident, and more artistically consistent. The look of Votoms changed quite a bit as different animation directors came and went over its year of production. This time, Shioyama kept a steady hand on the wheel and the show maintained its design fidelity from start to finish.

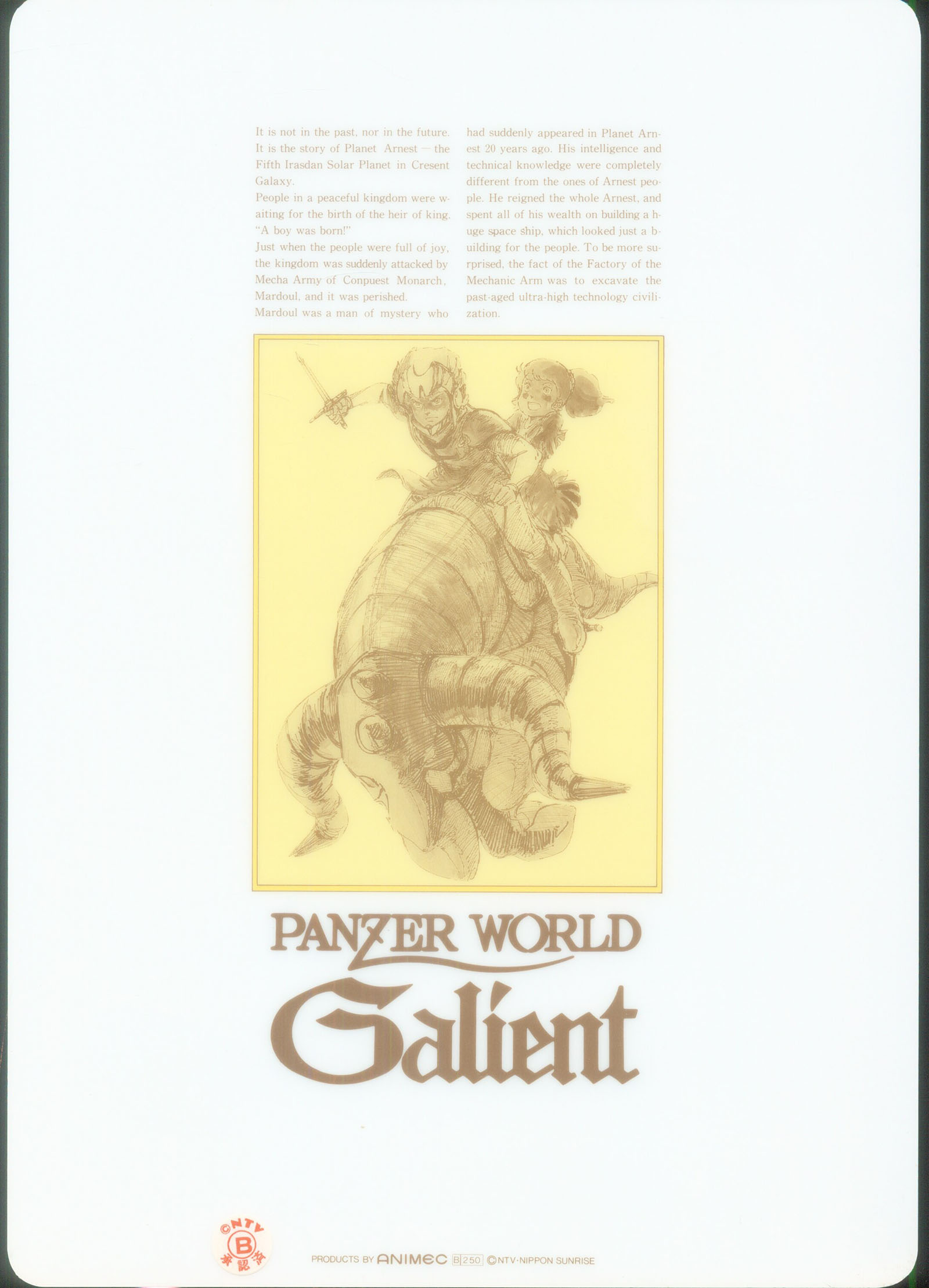

This craftsmanship continued – and improved – in Crest of Iron, an OAV (direct to video) that arrived about a year and a half later. It was what we now call a “reimagining” with variant versions of the characters in a different story contained within a single hour. The plot was paper thin, but the design and animation are still exquisite, some of the best the 80s had to offer.

The series has yet to be imported for a western release, but there’s a lot more to talk about! Click on the links below and keep reading to get a bigger taste of Panzer World Galient.

Series data

Original broadcast: Oct 5, 1984 to March 29, 1985

Director: Ryosuke Takahashi

Head writer: Soji Yoshikawa

Scripts: Fuyunori Gobu, Jinzo Toriumi, Soji Yoshikawa

Music: Toru Fukui

Character design, chief animation director: Norio Shioyama

Mecha design: Kunio Okawara, Yutaka Izubuchi

Producer: Toru Hasegawa

Animation Production: Nippon Sunrise

Main sponsor: Takara

Theme song composition: Daisuke Inoue

Theme song lyrics: King Reguyth, Yoshio Miura

Theme song performed by EUROX

Sunrise’s official Galient site

Galient page at Japanese fan site Battling

Anime News Network’s page on the TV series

Anime News Network’s page on the OAV

Galient footage in Super Robot Wars BX video game

TV series mecha index at MAHQ.net

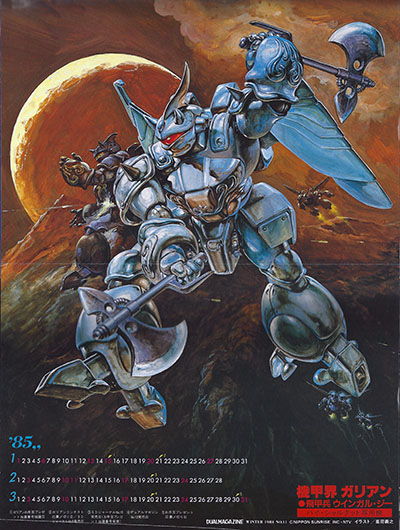

The series benefited greatly from the striking art of Yoshiyuki Takani,

one of Japan’s most popular fantasy painters. His art was used extensively on product packaging.

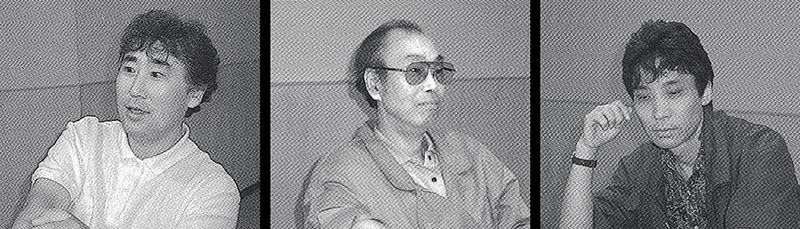

Round table discussion from the 1991 Perfect Collection LD box set

One of the major attractions of Panzer World Galient is its skillful portrayal of characters and rich drama.

Director Ryosuke Takahashi gathered to talk with screenwriters Jinzo Toriumi Ginzo and Soji Yoshikawa. We asked them to tell us the secret story of the production.

Ryosuke Takahashi is a member of studio Akabanten. He has worked on a number of robot films. His stories have many fans. His representative works include Dougram, Votoms and SPT Layzner.

See his ANN profile here.

Jinzo Toriumi is president of Hou Kobo. Veteran of many SF animation productions. His works include Gatchaman, Casshan, Tekkaman, and Votoms.

See his ANN profile here.

Soji Yoshikawa has a wide range of talents including scriptwriting, directing and character design. His representative works include Dougram, Votoms, Lupin III, etc.

See his ANN profile here.

New project Galient

Interviewer: Could you tell us about the concept of Galient when you first started working on it?

Takahashi: To tell you the truth, the biggest thing was that I wanted to do something different after working on Dougram and Votoms. Realistically, you can’t really change your new work from what you did last year. But back then, even if what we did last year was well-received, we were in the mood to change the next one. So from Dougram to Layzner, every one is different. It’s pretty exhausting. But I wanted to change something. And also, Character Designer Norio Shioyama wanted to do something like that.

Yoshikawa: That was a big part of it, wasn’t it?

Takahashi: Yes, it was. It was big.

Interviewer: Did something like a worldview come first?

Takahashi: That’s right. I wanted to tie in robots with something like a medieval cavalry. That’s what I had in mind.

Yoshikawa: You’d been saying for a while that you wanted to do sword fights in anime. So you had the idea of combining old things with robots from the beginning.

Takahashi: Yes, both Shioyama and myself.

Yoshikawa: When I heard that, I was all for it. Surprisingly, there aren’t many works in this trend.

Interviewer: How long were the writers involved in the project?

Takahashi: At that time, I knew from the planning stage that I wanted to work with these guys.

Toriumi: I joined Votoms in the middle. That series didn’t have any kids, so to make a change I thought, “Let’s include kids this time.” Unlike on Votoms, this time I could write from the very beginning. It was a lot of fun.

Galient‘s worldview

Yoshikawa: In recent anime, they don’t care much about building their world properly. They just say it’s some other world. But we can’t think about anything without that, can we?

Takahashi: My mind can’t go any further.

Yoshikawa: What I remember is the radio drama New World Story. I was convinced that it had that kind of image. (Translator’s note: this refers to a 1950s historical drama for children broadcast on NHK.)

Interviewer: Do you start after you boil down all the concepts?

Takahashi: No, it’s not that complicated. We just make the pillars. In other words, a robot is not something that someone invents and develops. It’s something that’s buried in the ground. Otherwise, the worlds of sword fighting and robots would not fit together. That’s why I decided to place it in a different era.

Yoshikawa: Mr. Shioyama wanted to do something more like Conan the Barbarian, right?

Takahashi: Shioyama-san is like a young painter turned 50. He has his own ideas about what he wants to draw. He wants to draw strange animals, for example. I thought it would be nice if we could make good use of them in the story. I don’t like it when animals appear out of nowhere and have nothing to do with the story. It’s very unsatisfying.

A staff with many ideas in common

Interviewer: Could you tell us about the writers from the director’s point of view?

Takahashi: Galient was pretty cohesive, wasn’t it? Votoms was a bit of a mess. There were two different stories going on, one written by this person and one written by that person…

Yoshikawa: Votoms was a desperate effort for each of us. Compared to that, Galient didn’t give us much trouble. There were no ups and downs.

Takahashi: I’m sure it’s because we had a common concept, like New World Story. We’re all close to the same generation. On Votoms, each of us came in with a different feeling, so it was hard to come up with common ideas.

Yoshikawa: But one thing we all have in common is that we don’t make anything new. (All laugh)

Toriumi: We’re all old-fashioned (laughs).

Yoshikawa: We’re not just old, we’re conscious of it. If you really wanted to get that feeling, you get young people on your staff. People who just started yesterday.

Toriumi: The worldview is apocalyptic, but there are classical images too, right? It’s interesting to see the imbalance between the two.

Interviewer: So was it easy for you to work together in the meetings?

Takahashi: Yes, I think so.

Yoshikawa: Yes, it was. It wasn’t all like this (makes a fighting gesture). (Laughs)

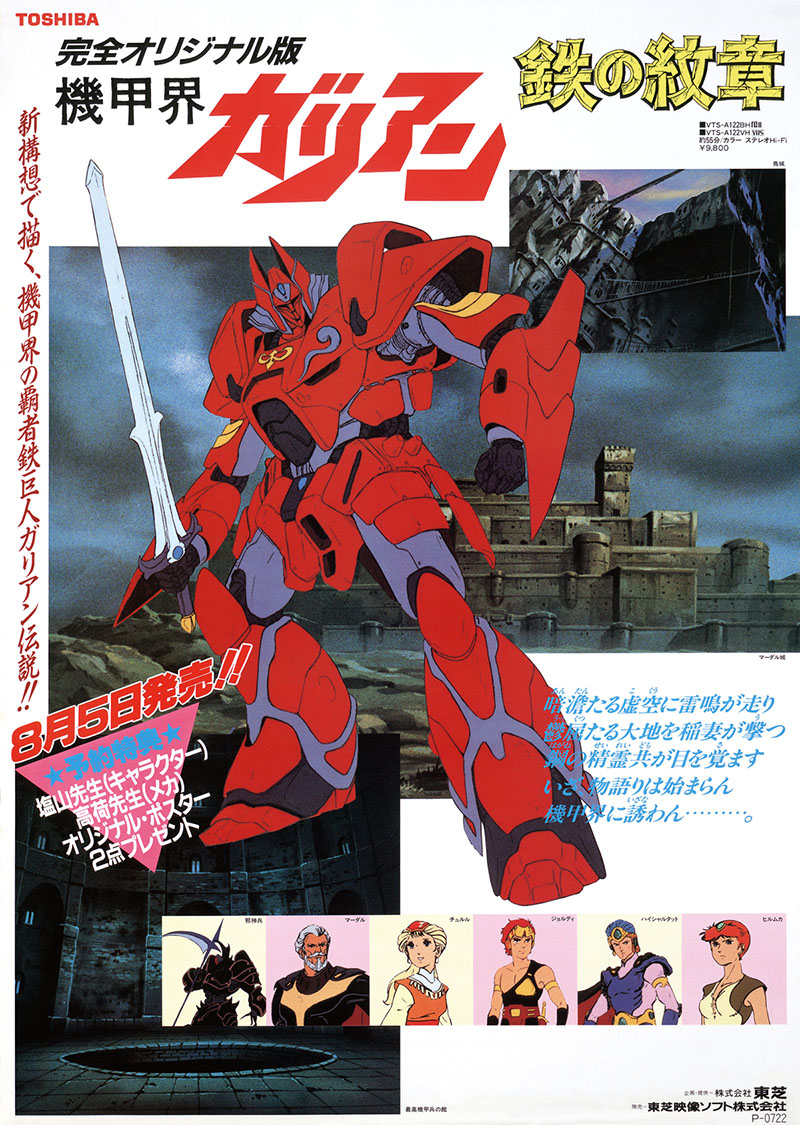

1984 model kit ad, Takara

Takahashi: No, it wasn’t. It just went on and on and on.

Yoshikawa: That’s something to think about.

Takahashi: I was sure I would suffer in the second half because the creative part was over.

Yoshikawa: The first part of the story flowed rather smoothly, didn’t it? I didn’t have any questions about what to do with this story. (Laughs)

Interviewer: I think it’s a stable but flat story.

Yoshikawa: We felt that we needed that to some extent.

Toriumi: So there was a kind of unspoken understanding that was unified throughout the work.

The actual work of the writer

Interviewer: What do you think of director Takahashi from a writer’s point of view?

Yoshikawa: I like him, but he’s a little different from my generation, though. (Laughs)

Takahashi: If you’re over 40, we’re the same (laughs).

Yoshikawa: I think we think the same way. We both want to take the high road instead of the main road. I always know I’m going to have fun. (Laughs)

Toriumi: We’ve worked together on Votoms and Galient, and those worlds are really interesting. However, there are three of us. We have to constantly keep track of each other’s direction. We do that rather smoothly, though.

Yoshikawa: In the case of Galient, we didn’t have a lot of “yes, we all agree,” it was more like, “Of course you’re going to do this, of course you’re going to do that,” (Laughs)

Takahashi: After all, if there’s no suffering, you’re doing something wrong.

Yoshikawa: On Votoms, I’d go away for a couple of episodes and come back, and I’d be like, “Oh, my God. What’s happening?” (Laughs) Even though we were working on it together.

Toriumi: The development was too smooth.

Interviewer: How do you make sure that each story is consistent in a work with such strong continuity?

Takahashi: It’s very easy when the director writes all the plots. Even if he can’t write them due to practical problems, he manages the work as if he were writing them. (Laughs)

Yoshikawa: You basically wrote Galient, didn’t you?

Takahashi: I wrote the most on Votoms, though there were times when it changed quickly during meetings. I wrote desperately on that one. In the case of Galient, I wasn’t aware of it, or I don’t remember much about it. I guess I just went along with the flow, thinking about what would happen next.

Toriumi: There were a lot of changes in the middle of the story, like the addition of characters.

Interviewer: Are the scripts faithful to the plot?

Takahashi: No, not at all (laughs).

Toriumi: Because plots are just bullet points. It’s better that way, though. It’s not as interesting when they’re written in detail.

Takahashi: The script process is completely different from plotting.

Toriumi: It works well because you write out the story points for the whole series, then we can think about the other parts of the story.

A classic hero

Interviewer: I’d like to ask why you set the main character Jojo at that age…

Takahashi: I wanted to make the protagonist of Galient a very happy, healthy, and cheerful person. The main character of Dougram (Crinn Kashim) is still troubled at the end, and hasn’t changed that much since the beginning. The main character in Votoms (Chirico Cuvie) was also like that. I wanted to change it up a bit and make him more of an easy-going, energetic prince.

If I were to make it now, I feel like it would be better for business if I made the main character older. If we were to make the protagonist between 17 and 19 years old and tell the same story with the same worldview, I’m sure it would attract a narrower range of fans. I think that’s the wrong target. We all said, “Let’s aim for a wide range, not a narrow range.” But in the end it didn’t get any wider and we didn’t make any new fans (laughs).

Interviewer: What was the problem?

Takahashi: I’ve been thinking a lot about what we did with Jordy, the main character. The directing level has nothing to do with the writer. To put it simply, if you make the protagonist’s age that low [12 years old] you need about three times as much directing power as I have to expand on it. The protagonist, who is an easy-going person, has had his country destroyed. It’s a very standard story. If you don’t have the ability to make things exciting and interesting, it’s impossible to expand on it. In the end, my ability as a director was not enough. It wasn’t the ability of each individual, but the power of the director. That’s why afterward I thought it was a mistake.

Toriumi: I think, in the world of Galient, the story would develop differently if you made the protagonist 17 or 18, but there are ways to make it work.

Takahashi: The atmosphere is completely different, though. At that time, I refused to make anything like that. I was trying to catch hardcore fans in a limited space.

Yoshikawa: You must have had some kind of backlash (laughs).

Takahashi: But you liked that world, didn’t you?

Yoshikawa: I did. It was a bit sweet for my taste. (Laughs) But there was no suffering at all.

Mardar, the true hero

Interviewer: How do you feel about characters other than Jojo?

Takahashi: The main character is Jordy, but the real protagonist in my mind is Mardar. Once I came up with him, the story was over for me, just like that. (Laughs) It’s like my disease, wanting to depict something other than the main character.

Interviewer: He’s a challenge for the Alliance of Advanced Civilizations, isn’t he?

Takahashi: In my mind, the Alliance of Advanced Civilizations is like a world of insects, where each individual is completely controlled. Mardar is born into it like a throwback to when they were human. Mardar is a brilliant man, but he’s hard to control, so he manages to escape and becomes a powerful figure on the planet Arst. He gains power there and challenges the Alliance, which is the main part of the storyline. But it happened too quickly, so it ended in a few episodes. Come to think of it, there was also the Erazer.

Yoshikawa: We had to force that in at the end, didn’t we?

Takahashi: It couldn’t be helped. In short, it’s an eraser. Besides Mardar, there weren’t many other interesting characters in that world.

Interviewer: I think Hilmka is also a key character in the story…

Takahashi: Hilmka is a strong-willed woman who doesn’t flinch, so her name became Hilmka. She’s the only one with such confident naming. It’s perfect, don’t you think? Maybe it’s just me. (Translator’s note: in Japanese, “hirumka” is a term for “not to be taken lightly.”)

Yoshikawa: I thought I was the one who thought of that.

Takahashi: When I heard the sound of Hilmka, I thought it was perfect. I just thought it matched her temperament.

Yoshikawa: Hy Shaltat is Take-san, isn’t he? (A nickname for one of the other writers, Fuyufumi Gobu.)

Takahashi: Yeah. He looks like Take-san.

The appeal of Galient mecha

Takahashi: In the armor world era and the warring states period, there were the weak and the strong. The people who gathered in the White Valley escaped to there using the space-jump transfer base. When we were developing the story, they had built something to protect themselves from the beastly ones, the ones who take the law of the jungle for granted. That was Galient.

Interviewer: So the design of Galient was a little different from the others.

Takahashi: I think the design of Galient is more coherent than all the other robots. It’s a good design. Also, the water-mecha that uses the spear.

Toriumi: Yeah, the mecha in Galient all had their own personality.

Yoshikawa: I like them, too. It doesn’t flow with the modern style. There are a lot of otherworldly stories nowadays that flow in a modern style. Even if they look feminine.

Toriumi: Some works make the backstory ambiguous, then a robot appears and suddenly a child can control it. I feel a lot of resistance to that. If there was a manual or something like that, I could accept it.

Interviewer: There was a depiction of light enveloping Jojo…

Toriumi: If you do something suspicious somewhere, you can always come up with a reason later (laughs).

Narration is like a dog’s…

Interviewer: In your works, you seem to be very particular about narration…

Takahashi: Well, it’s very simple. Narration can really set the mood of a series. So if I put my intention into it, it’s easier for the audience to understand than the other parts. I put my own scent on it to show that I did it, like when a dog pees.

Yoshikawa: I like the atmosphere created by narration.

Takahashi: Yeah.

Toriumi: Azbes’ lines were easy to write. Hy Shaltat was hard to write.

Takahashi: The kind of writers I work with now can write a Hy Shaltat-type very easily. On the other hand, they can’t write for someone like Azbes.

The phantom episode

Takahashi: We rushed the story at the end, didn’t we? We originally had 50 episodes in mind, so we had to make do.

Toriumi: It worked out to two arcs. (Translator’s note: a single arc is defined as 13 episodes.) Up to about five or six episodes before the end, I still thought it would last a year.

Takahashi: I thought it would go on for 50 episodes. I feel like it shouldn’t have ended there.

Yoshikawa: You can’t prove it (laughs).

Interviewer: If it had continued for a year, what would the story have been about?

Takahashi: Mardar was going to move to Planet Lanplate, so that part was the same. But Jojo and the others wouldn’t be going with him, they’d be chasing him in some way. Then the battle continues for a while in a different setting. They catch up with Mardar and win at least once. But before he dies, you hear about his purpose, and you feel a certain sympathy for him. That’s when the Alliance of Advanced Civilizations comes to the rescue.

Interviewer: But that doesn’t mean that the Alliance would use mecha, does it?

Takahashi: No. If they could do without, they wouldn’t have to fight, they would just activate something like the Erazer. Something inhuman, something automatic. And all the characters would be up against it. Maybe Jojo and Hy Shaltart would join forces. And their battle would cause some kind of ripple effect throughout the Crescent Galaxy. That’s how it would have gone.

Interviewer: It seems like the ending of the actual final episode would be a little easier to understand.

Painting by Mecha Designer Kunio Okawara

An easy-to-watch production

Takahashi: I think this work was a little bit out of breath, wasn’t it?

Toriumi: I guess we were tired after Votoms (laughs).

Yoshikawa: Overall, I like it. There are a few parts that I don’t like, though.

Takahashi: I sort of feel like it was a waste of time. If I had taken a break for about three years, it might have been completely different.

Toriumi: But we’re all the same because of our constitution. (Laughs)

Takahashi: This is a bad way to put it, but I think there was a part that turned me into an adult. For me, at least.

Toriumi: I think we all did.

Yoshikawa: But I like the fact that Galient was easy to watch. My daughter was 8 years old at the time, and she loved it.

Toriumi: Even little kids can watch it.

Takahashi: My mother also says that Galient is the most interesting compared to Dougram and Layzner.

Yoshikawa: Japanese anime relies too much on “skin sensation” and only stimulates the surface nerves. That’s not the case with this. It’s a simple, straightforward story, and I think it would be good to have more of that. On the other hand, maybe we could have thought of some more exciting elements, too.

Takahashi: If we were doing it now, I’d think about adding a little bit of that. These days, I can’t separate my work from the commercial side. At the time, I didn’t think about it at all.

Toriumi: It’s not a matter of consideration to leave it in. It’s in your nature.

Yoshikawa: There are very few works that consider the audience as much as this one. Even Votoms had a certain amount of thought put into it. (Laughs)

Takahashi: I was just thinking about that today.

Interviewer: It might be tough to buy an LD box and read the book and find only remorse (laughs).

Yoshikawa: No, talk like this is valuable. (Laughs)

Interviewer: That’s right (laughs). Thank you very much for taking time out of your busy schedule today. I’m looking forward to your next work.

Art Gallery