Freak Angels, 2022

Every single TV cartoon I’ve ever worked on had its own unique headdesk moment at some point during the production. They’re inevitable. Nobody can foresee all the consequences of their decisions.

Sometimes it’s merely annoying, like getting “final” scripts that aren’t ready to be visualized, and have to be rewritten on the fly. Sometimes it’s more serious, like having multiple bosses who make you stop working until they finish battling for veto power. Sometimes it’s catastrophic, like having your entire show canceled while it’s being animated. I’ve personally experienced all of these scenarios and more.

Occasionally, a headdesk moment will benefit me, like when it happens to someone else and they hire me to help put out a fire. That’s how I got involved with Freak Angels. And it was the first time I actually got to work on an anime series, which was an unexpected surprise.

Quick sidebar on how I apply the term “anime,” since there’s been some debate about this: If a movie or show is animated in Japan by Japanese artists, it’s anime. If it’s animated anywhere else in the world by non-Japanese artists, it isn’t. Of course, there are grey areas and hybrids. Maybe someday we won’t need to make distinctions. But at this moment in time, the word has its own specific meaning and is not interchangeable with other words. This is why words exist, and that’s how I apply it. (I used to insist that anime also had to be written in Japan, but Freak Angels softened me on that position.)

Freak Angels was animated in Japan by Japanese artists. The concept originated in a graphic novel series written by British author Warren Ellis and British artist Paul Duffield. It takes place many years after an apocalyptic event has flooded London, turning it into an isolated island controlled by a group of powerful young psychics. Over the course of the story, they are revealed as the cause of the apocalypse and must decide what kind of future they will seek. Fair warning, it has a “Rorschach” ending. Your response to it will reveal you as an optimist or a pessimist.

Six volumes were published by Avatar Press from 2008-2011. Afterward, it worked its way through a maze of cause and effect to land in the hands of Crunchyroll and got greenlit for an anime adaptation in 2017.

I first learned in 2018 that Crunchyroll was going to start making original content when their exec producer invited me to lunch and expressed an interest in getting me involved in a directing capacity. The concept of “Crunchyroll Originals” was explained to me as an attempt to create “anime-adjacent” content that would attract audiences who weren’t quite ready for the real thing. A “gateway drug,” so to speak.

I ended up not getting to direct any of these projects, but some headdesk moments resulted in me getting hired to help put out fires. The first was on High Guardian Spice, which I’ll cover at another time. The second was Freak Angels. So here we are.

To explain the Freak Angels headdesk moment, I have to explain something about directing cartoons. I’ve been a director since 1997, and many have asked me what that actually means. It’s a good question. We sort of know what a movie director does. How does that translate over to cartoons? In truth, it’s pretty much the same. A director decides how to visually interpret a script. They decide what you’ll see in any given shot. They decide what’s in the shots before and after the one you’re looking at. They decide where the lights are, what direction we’re traveling, how long a shot should last, what the actors are doing, whether the camera’s moving or not, etc.

A live-action director and a cartoon director both do these things with the help of a crew. But the two skill sets are not interchangeable. A live-action director has it much harder, since they have to constantly explain to everyone around them what the goals are. A cartoon director just draws it in a storyboard.

So how is a cartoon director different from a storyboard artist? Think of them as the “chief” storyboard artist, charged with overseeing a crew of artists and stitching all their work together into a complete, coherent story. You become a director by showing a consistently strong ability to interpret a script as visuals that make sense, are fun to watch, and are economically efficient (achievable within the budget and schedule).

That’s the work of a director. In TV production, they’re referred to as an “Episodic Director.”

The next step up the ladder is “Supervising Director.” They’re in charge of however many episodic directors it takes to make a TV series. They keep their eye on the overall production, interfacing with multiple departments to make sure everyone produces what’s needed at every stage. In rare cases, like when you have a smaller-than-usual episode count, the Supervising Director can also be the Episodic Director for a whole project. This, I believe, was the case with Freak Angels. At least at the beginning.

(Incidentally, there are also timing directors and animation directors, but we’re already far enough into the weeds here.)

Scripts were written on the US side, supervised by the showrunner, and an anime studio in Japan was engaged to take it from there. Everything visual would happen on the Japan side with approvals on the US side. Supervising Directors in Japan tend to know what they’re doing, so it was natural to trust one of them with the series. Plus, it was only nine episodes long. How bad could it be?

As it turns out, bad enough for a headdesk moment. When the first storyboards came out of the oven, they were all over the place. Some were focused and precise and imaginative (easy to animate). Others were ambiguous, surreal, and abstract (hard to animate). Sometimes the tone of the script was there, other times it had been lost. There were also instances where the script had simply been ignored. So what happened?

One of the first things I learned as a director – for reasons of personal sanity if nothing else – is to ask how much latitude you have to interpret a script. If the writer isn’t fussy, you can make a lot of changes. Some writers love to see how far you can take their ideas. Others, not so much. When I worked on Futurama, for example, we were ordered to cut apart and physically paste lines from the script onto the storyboard as proof that we weren’t changing anything. It’s vital to get that question answered going in.

The Japanese director of Freak Angels did not feel the need to ask that question, because in Japanese productions the director typically has veto power over the writer. It is most certainly NOT that way in the US. Cue the headdesk moment. The nature of the production beast is that by the time you recognize these sorts of problems, they are already systemic. The plane is now in the air, so you can’t just slam on the brakes. You’ve got to adapt in flight.

This is when phones start ringing and fire fighters are called to the rescue.

The first fire fighter on the scene was Audu Paden, my mentor on shows like Extreme Ghostbusters and Godzilla. He reviewed the early episodes, some of which were too long and flabby. The predetermined length was 24 minutes per episode, and some timed out to over 30, so they needed whipping into shape. By this time, a couple years had already passed and the show was drastically behind schedule. Animation couldn’t begin until the animatic/editorial problems were solved, so there was no time to spare. By recording temp dialogue and revising the storyboards into tight animatics, the rough edges were shaved off and the episodes brought down to their correct running length.

By doing this, Audu effectively assumed the post of Supervising Director and took control of the plane. He restored the focus of the story back to what the scripts called for, but there was only so much he could do on his own. That’s when my phone rang and I put on my fire fighting gear.

It was January 2020. My time at Marvel Animation Studio was winding down with fewer and fewer projects to fill my day, so I had room for more. Audu explained the overall situation, and I was excited by the prospect of creating storyboards that would go to Japan and become the basis for an actual anime series. Until then, every show I’d ever worked on had been animated in Korea based on American-made boards and designs. The model sheets Audu gave me to follow were authentically Japanese and a delight to work with.

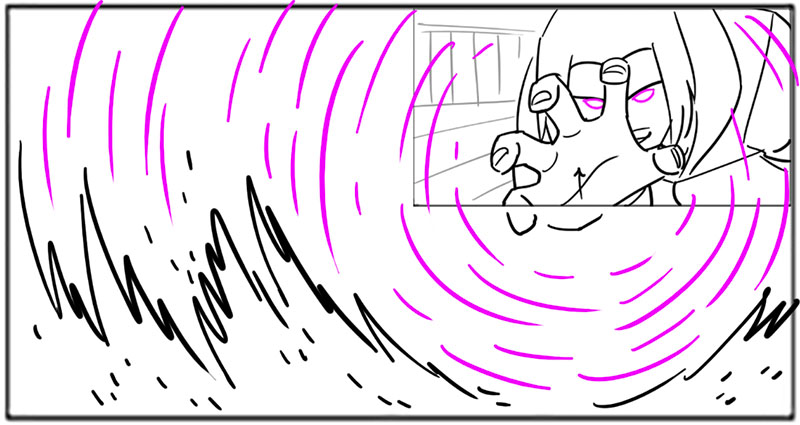

Some rough animation existed by this point, and I was immediately impressed by how good it looked, especially the backgrounds. I assumed they were built in CG and was astounded to learn that they were not. Pre-made textures were applied where possible, but the vast majority of what I saw was hand-painted. Not all of the character animation was perfect, but I recognized the hallmarks of modern anime techniques and was energized by the chance to work in a mature, adult-oriented filmmaking style.

I worked on two consecutive episodes, 7 and 8 (of 9). In both cases, the Japanese storyboards strayed too far from the script and seemed more like a series of freeform sketches that didn’t tell a coherent story. It wasn’t a storyboard by any definition, and could not be extrapolated into animation. I couldn’t imagine how a director even allowed them to slip through, but there they were. And out they went.

I was given the scripts and told to start fresh. I’d worked with Audu more than enough times to know what he would want to see (the main reason he keeps hiring me), and I knew exactly what information an animator would need to construct a shot. I also knew that Japanese storyboards are generally rougher than American boards. There’s a good reason for that; it’s because they stay “in house.” I esplain…

If you’re drawing boards that you know will go to another country and be animated by someone you’ll never meet who probably doesn’t speak or read English, you have to put a LOT of information into them. They become a contract and a blueprint. In many cases, they are the equivalent of key animation with precise timing and movement. If you leave anything out, you can’t rely on an animator to put it back in. But if your boards and your animation are done under the same roof, as in a Japanese studio, the director is always there to communicate with the crew. So a storyboard doesn’t have to carry quite so much weight.

For Freak Angels, I landed somewhere between those two extremes. I didn’t have to worry about detail, just structure and movement. Based on what I heard later, I got it exactly right. The Japanese director LOVED my boards because they took away all the guesswork and he knew precisely what to do with them. He asked Audu to hire me for more, but regrettably I could only spare enough time for two episodes.

My part of the project was over in about in a month, but there was still much work to be done. After all the episodes had been fully boarded, new headdesk moments occurred when finished animation began rolling in. The same problem that plagued the boards arose again; some sequences were exactly on point while others were unusable. For some reason, the Japanese director just wasn’t focused. But again, the plane was in the air. These fires had to be put out in flight.

There are many ways to deal with retakes. In an ideal world, you just keep sending shots back to the animators until they get it right. But in the real world, the production schedule prevents this from happening. If they have to keep going back and fixing previous shows, current ones don’t get done on time. Thus, it’s very easy for retakes to create a cascading effect that could crash the plane.

So, even if you’re completely justified in sending work back for fixes, you look for every possible reason not to. Sometimes, you can fix mistakes with clever and intricate digital solutions. We call it “Frankensteining,” since it involves pulling shots apart and stitching them back together. This can range from correcting mouth movements to patching up art mistakes to repurposing shots from elsewhere. The key is to stay flexible and be prepared to abandon your original plans if you simply can’t afford them any more.

I’ve been through retake madness on many shows, and it’s never fun. But it has gotten easier in the digital age, when image manipulation gives us access to more solutions. If the animators don’t give you what you ask for, you stand a much better chance of being able to synthesize something else that still gets the job done.

In order to stay sane, it’s vital to remember that the viewing audience will have no idea what you originally asked for or what the animators did wrong; they’ll only know what they see in the end product. Your job is to make it as good as it can be with your limited resources. If you successfully land that plane, someone will usually pay you to land another one.

All nine episodes of Freak Angels were completed and released in January 2022. They can be seen for free on Crunchyroll here. The ad breaks are seriously intrusive, but not a dealbreaker.

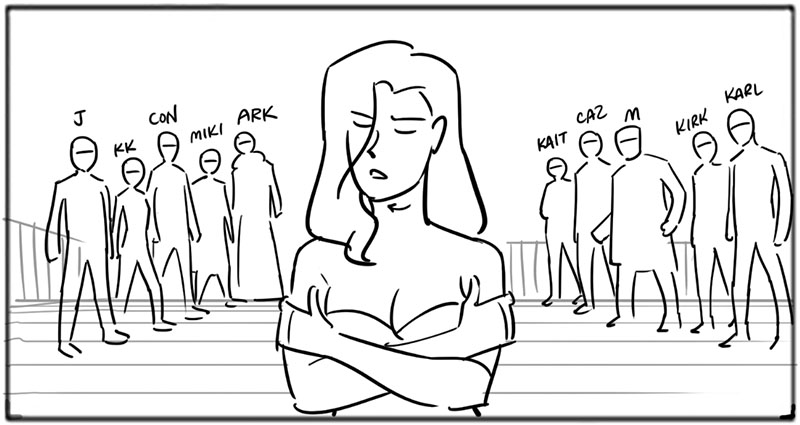

My storyboards

Episode 7

This segment started from script and included a tense cat-and-mouse stalking scene through a junk yard stacked with wrecked cars.

Episode 8 segment 1

This was the first time I got to work on a Japanese-style storyboard format, quite different from the American standard. But a lot of it ended up being cut for time.

This segment started from script and was a significant turning point in the series in which all the characters came together to decide their future.

Nice insights, can’t wait to someday learn more about High Guardian Spice (as an actual fan of the show)!