Godzilla The Series, 1998

Like all red-blooded American boys growing up in the 70s, one of my greatest heroes was a Japanese lizard.

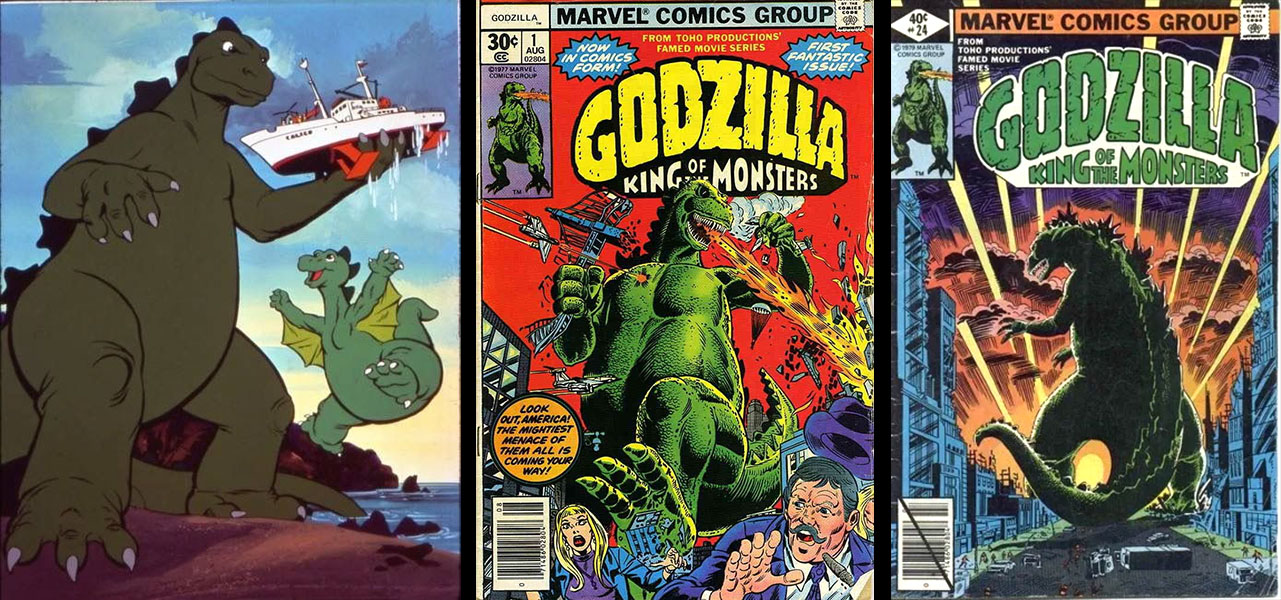

I have no memory of when I first laid eyes on Godzilla, but from that moment on he (it?) was part of me. I constantly scoured TV listings to look for when the next movie might be on. Whenever I found one, I dutifully recorded it on audio cassette (later VCR) to relive forever. There were already 15 of them back then, but they were as rare as gold nuggets – which made them even more precious. I lucked out and saw two of them (Mecha Godzilla and Megalon) on the big screen. I watched every episode of the crappy 1978 Hanna Barbera cartoon and pretended it was a decent stand-in even though it obviously wasn’t. I got all 24 issues of the Marvel comic and read them endlessly.

You won’t be surprised to hear that I also made my own comic book at one point (which I really wish I still had) titled Godzilla vs. IT. When the big guy came back to screens in 1984 (1985 in the US), I was all over it from then on. Since then, I’ve seen more films in theaters and marathoned the entire Toho kaiju catalog twice at home (30 movies in 30 days, try it sometime).

So yeah, you could say I’m a Godzilla guy.

Just imagine, then, what it was like to hear that after Extreme Ghostbusters wrapped production in the fall of 1997, our next series was going to be…Godzilla!

This was one of the benefits of working at Sony Animation, one of the busiest animation studios of the late 90s. It was affiliated with Columbia Tri-Star, which is how a whole bunch of movie properties got turned into cartoons: Ghostbusters, Men in Black, Jumanji, Starship Troopers, and others. Tri-Star was the studio that made the first American Godzilla movie (released Memorial Day Weekend 1998) and we were in exactly the right place to turn it into a Saturday morning cartoon.

But the ’98 Godzilla SUCKED, right? Is that what you’re saying? Even so, that doesn’t mean a followup cartoon also had to suck. And apparently it didn’t. When I did research for this article, every review I found was glowing. “Better than you remember!” “What the movie should have been!” We didn’t hear these accolades until much later, long after the show was a distant memory for those of us who worked on it. But simply by virtue of it being 40 episodes long, there HAD to be more going on with it. It absolutely benefited from a broader playing field and a host of crazy giant monsters.

It was interesting for all of us at Sony to “graduate” from Ghostbusters academy into this new project. It gave us a unique vantage point of the movie as the buzz was rising and everyone was imagining the best outcome. We saw a lot, we learned a lot. And I remember plenty about it, so let’s get started.

First and foremost, there was the secrecy. I don’t remember any film before it having such a rigidly-controlled media campaign (Phantom Menace hadn’t happened yet). The new monster design was closely guarded and militantly protected. We all had to sign strict non-disclosure agreements to work on the show. If we leaked anything, the entire production would be shut down and we’d be out of a job. (I recall hearing that someone did leak something at some point, but it wasn’t traced back to us.)

To create some measure of protection, we worked under a pseudonym. The announced title of our show was HEAT Seekers. There was a fake logo for all our documentation, and it was to feature a giant monster called Gorgon. Actual press releases went out with this information, though I never got to see one.

This secrecy extended to every production partner and licensor of the film as well, over 300 different companies. These days it’s standard operating procedure for every big movie. Back then it was all new and kinda sexy. It made you feel powerful to know that your loose lips could sink ships. And we all did our part to protect the lizard. Mark that point, because I’ll come back to it later.

There was a standalone teaser trailer that caught everyone’s attention (which flipped a finger at Jurassic Park), and the “Size Matters” billboard campaign. For several months leading up to the release, billboards popped up in L.A. and elsewhere. “His foot is as long as this bus.” “He’s taller than this building.” “His cloaca is the size of this sewer lid.” I made that last one up, but you get the picture.

As an aside, I think someone did a post-mortem on this and found that none of these claims actually held up, but nobody cared after the fact. It was fun to drive around and see such a huge campaign and know that we had a stake in it.

What we didn’t have, for quite a while, was a Godzilla design to draw in our storyboards.

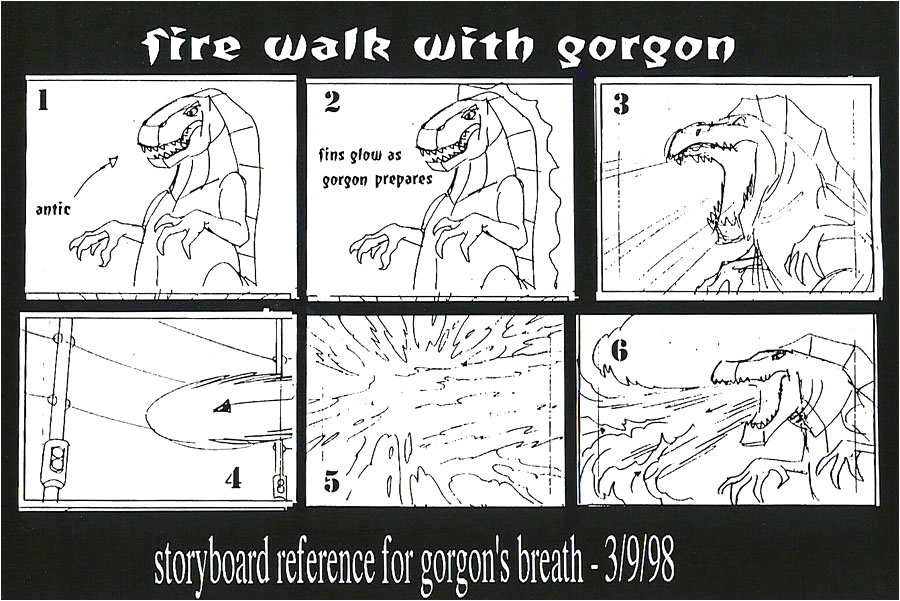

That was how far the policy extended; none of us was allowed to see the star of our show even though we had to create action scenes for him/it. We could work around this obstacle up to a certain point, but we couldn’t finish an episode under that restriction. At one point I asked if we could just draw the original Godzilla as a placeholder, but our Supervising Producer Audu Paden had seen the design and said they were too different to be swapped out. The best we could do on our own was to put in a sort of T-Rex with fins on its back (shown below) until someone did the sensible thing.

Storyboard reference for the atomic breath (based on my drawings from an episode).

“Fire walk with Gorgon” was a Twin Peaks joke.

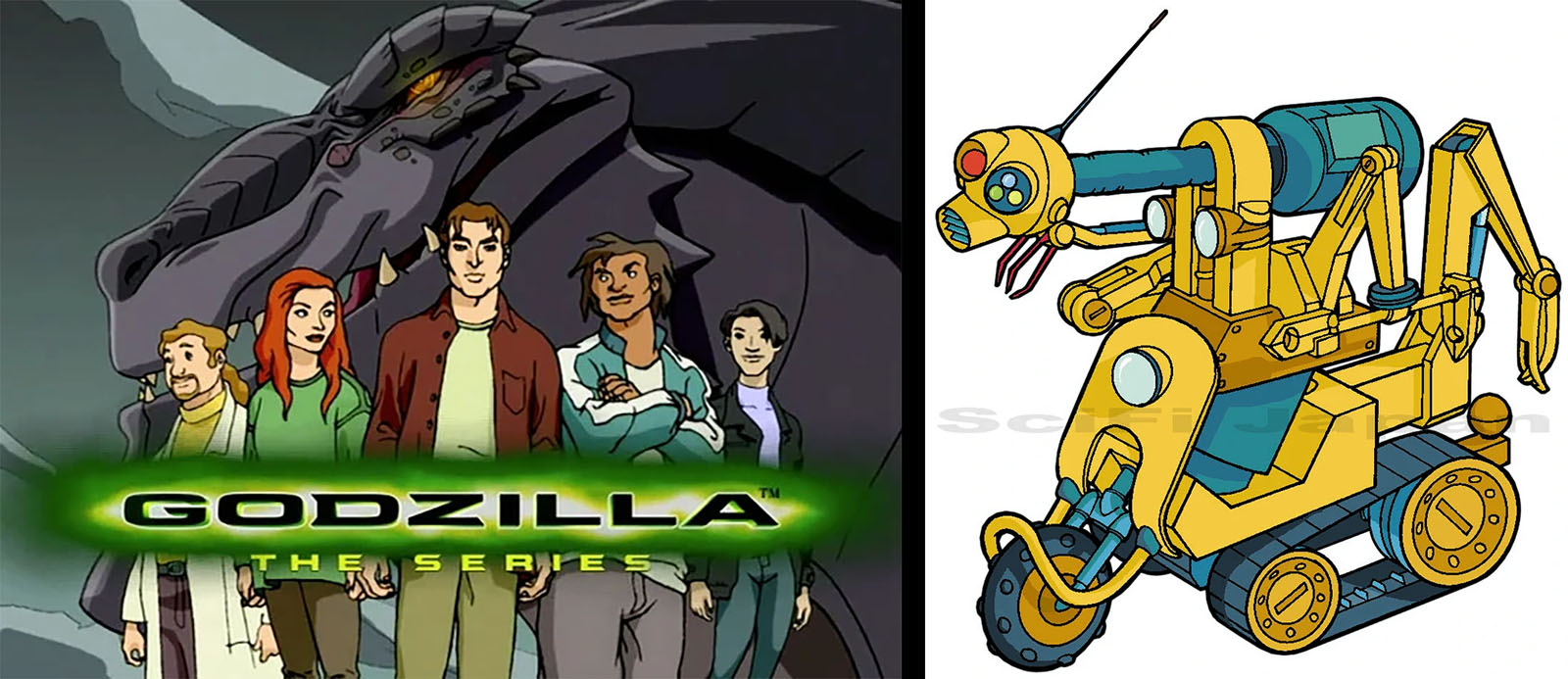

There was also a struggle to design the humans. Fil Barlow, who led the character design team on Extreme Ghostbusters, continued forward on this show, but his first couple rounds didn’t light any fires. I remember Audu Paden calling all of us directors into a brainstorm meeting to see what we could come up with, and I brought a handful of anime art books to stimulate some thinking. Unexpectedly, Fil walked in, bleary after an all-nighter, and dropped his third round on the table. We all had a look and were very impressed. He left to take them upstairs and Audu said, “I don’t see any further need for this meeting.” So that problem got solved.

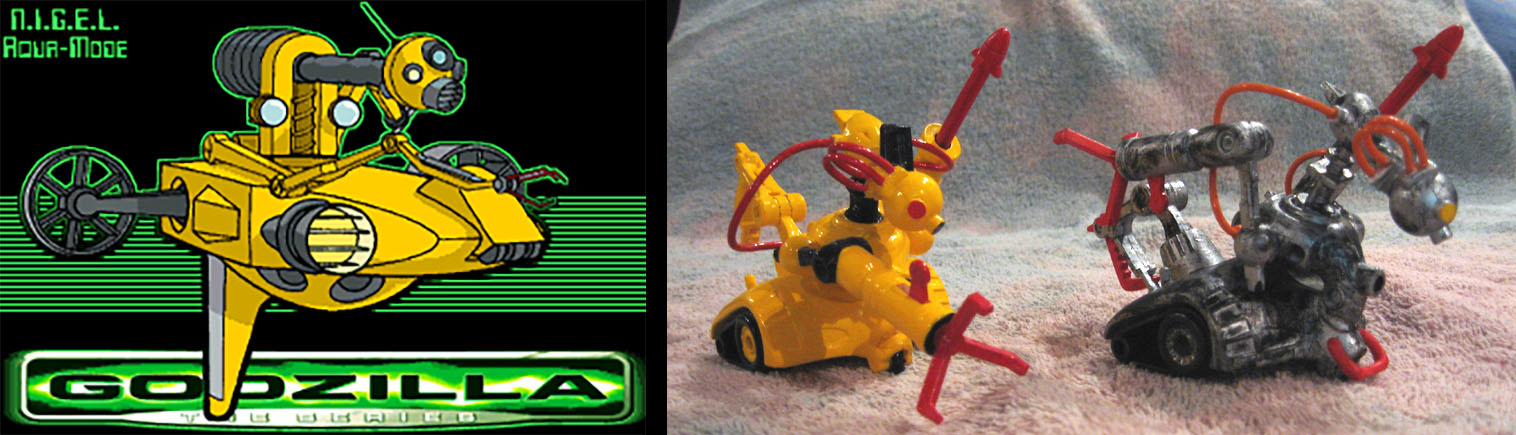

There was a non-human/non-reptilian cast member that still needed attention, a robot named N.I.G.E.L. It needed to look goofy and primitive, cobbled together from junk. I was given a crack at him and somehow managed to nail the design on the first try. There were land and sea configurations, since we went in the water a lot. The schtick was that N.I.G.E.L. would be smashed to pieces in every episode, then magically put back together for the next one (sometimes later in the same one). There was an action figure planned, but (A) it didn’t look much like my design and (B) the toy line never came out. Otherwise I could have added “action figure designer” to my resume.

We finally reached a point where the lack of a Godzilla design was actually stopping us from meeting our deadlines, so something had to give. One day, out of the blue, we all went on a field trip to a post-production facility where we would get to see some actual footage for the first time. It was my first visit to such a place, and it was…not impressive in the least. It basically looked like our office, divider walls and desks and workstations.

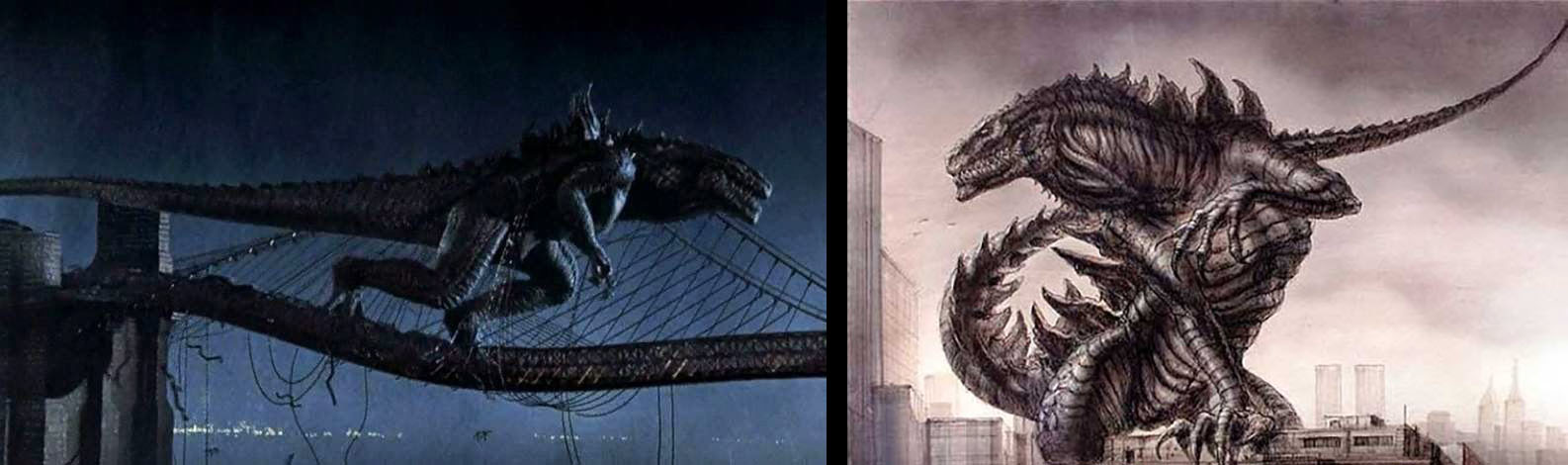

Somebody was processing CG effects on their desktop computer, specifically the bridge scene where Godzilla gets all tangled up and finally dispatched. We watched it a few times and thought, “THAT’S all it is?” I mean, there was nothing wrong with it, really, but it just didn’t live up to the hype. Anyway, the critical line was crossed and now we could finish the job we were being paid for.

Left: the bridge scene. Right: final monster design by Patrick Tatapoulos, which I never saw before writing this article.

It also allowed me to seriously get to work on the main title. This would be my third. The first was for Extreme Ghostbusters, in which I worked directly with our Exec Producer Richard Raynis. A few months later, he reeled me in for my second one: Men in Black. To this day, whenever I mention it everyone tells me they thought it was the coolest one ever. Which I never get tired of hearing. (Watch it on Youtube here and see the storyboards here.)

By this time I’d been drawing storyboards professionally for about a year and a half, but there were still new lessons around every corner. (There still are today, as it turns out.) As for the main lesson I learned from this show, I’ll quote myself from an interview I once gave to SciFi Japan…

“As a kid I loved seeing Godzilla movies on TV. They came around very rarely, so whenever one appeared it was like Christmas morning. Later, when I got older and special effects films became more sophisticated, Godzilla films stopped being about raw entertainment and began to pale. They hadn’t changed, of course, but I had. Entering the filmmaking business required me to have a critical adult eye that made it impossible to just be entertained by a Godzilla movie.”

“It wasn’t until our executive producer, Richard Raynis, put a fine point on it that I found the words to describe the gulf. Richard’s directive to me as I designed the main title sequence and directed my episodes was to keep the camera at human level as often as possible. In other words, don’t automatically fly through the ceiling every time a huge monster appears because it would immediately cancel out the realism. Instantly, I knew why the older films weren`t holding up any more; the cameras were almost always placed at monster level while filming the monsters and human level while filming the humans. Had the filmmakers picked one or the other and stuck with it throughout, it would have been a very different experience.”

“As flawed as the Sony Godzilla may have been in its story, I had to admit the images were riveting…and it was precisely because the cinematography followed this philosophy. I was glad later to see Toho pick up on this and apply it to the original Godzilla. It helped immensely to restore my respect and made it possible for me to be entertained again.”

Why don’t they look like giants? Because they were filmed like humans.

Then there was the eternal lesson about storyboard revisions. Settle in for some shoptalk here.

Nobody ever likes getting revisions, but they’re inevitable. You draw what you think works, then your director stomps all over it and makes you draw it again. That’s the negative way to look at it, and if you can’t get past it you won’t last long.

The positive way goes like this: you and your director are collaborating to find the strongest way to visualize the script. The first idea might be fine, but maybe it leads to something better. Draw subjectively, review objectively. Revision notes are not an insult, and taking them personally means your ego is more important to you than your job. Drawing storyboards for a living is like being in film school for a living. Except this film school pays you to learn. Which works out pretty well.

For a while I despaired that I would never get it right. No matter how hard I worked, Audu would always find something wrong with it. During my time on Godzilla, I came to realize I was looking at it the wrong way. Audu wasn’t finding fault, he was finding opportunities. Seeing a shot done a certain way would spark an idea for how it could be done better. Sometimes the reasons were technical (maybe it doesn’t connect strongly enough to another shot), sometimes practical (it will be easier to animate if you do it this way), and sometimes just for clarity (simplify that thing and the audience will get it quicker). There are countless ways to improve a shot, and your technique will improve if you’re open to them.

Over time, if you learn from experience, you start to anticipate revision notes and eliminate them before they happen. When you cross that line, you’re ready to direct others. I’ve worked on many more shows with Audu, and we both learn something every time we collaborate. I’ve gotten a few boards past him with no revision notes at all, but that’s just a reprieve until the next one.

We were a few months into production when the release of the movie finally approached. We all got a private viewing in a theater on the Sony lot, which was one helluva perk (we also got to see Men in Black and Starship Troopers before the general public). I think we were all in agreement that it was fun, but didn’t live up to the marketing campaign. That later turned out to be typical of Roland Emmerich films. The guy could promote like a master, but it would usually build up an invoice of expectations that the final product didn’t pay off.

And now the punch line. Remember what I said about everyone agreeing not to reveal the monster before the film came out? Well, someone did. And a bunch of us at Sony Animation saw it happen with our own eyes.

A few days before the premiere, some us went to lunch together at a local mall. The mall happened to have a toy store. As we walked past it, we saw an employee casually splitting open big boxes from Trendmasters. These boxes were clearly labeled GODZILLA: DO NOT OPEN BEFORE MAY 20. We could read them from outside the store. And yet, the employee was putting toys right up on the shelf as if the labels didn’t exist.

We went in for a closer look and one of the directors bought the biggest one: Ultimate Godzilla, a giant action figure that stretched a couple feet long. He took it straight back to the studio and put it up in his work space. Now we finally had all the drawing reference we needed.

That moment illustrated a valuable lesson: no matter how carefully you plan and no matter how many millions of dollars you sink into your secrecy campaign (about $80m in this case), you’re still at the mercy of your weakest link. In this case, one toy store employee who wasn’t paid enough to care.

Godzilla the Series debuted September 1998 on Fox Kids (Saturday mornings) and ran through April 2000 with a total of 40 episodes.

Home video releases began with two VHS volumes, then four DVDs (containing 12 episodes) in 2006. The complete series was released on DVD in 2014 (Amazon listing here). Two video games were released for Game Boy Color in 1999 and 2000.

Wikipedia entry on the 1998 movie

An article on the movie’s marketing campaign

Detailed history of the series on SciFi Japan

My Contributions

I visualized the opening title and contributed storyboards to the first two episodes. I directed two full episodes after that, then was transferred to the Supervising Director position on the PBS cartoon Dragon Tales in summer ’98. Which is a whoooole other story.

Opening title

See it on Youtube here (full length) and here (higher rez)

Episode 1: New Family, part 1

Aired 9/12/98

The series begins with a replay of the movie’s climax, after which Nick Tatopoulos discovers one of Godzilla’s eggs has survived. The hatchling escapes and by the time the team finds him again, he has grown into a massive adult. Godzilla recognizes Nick’s scent and imprints on him as his parent. The U.S. military, responding to a series of disappearances in Jamaica, attacks and seemingly kills Godzilla.

Trivia: Nick Tatopoulos is named after Patrick Tatopoulos, who designed the new Godzilla for the film.

Typically, the first episode of any animated series is directed by the overall supervisor and storyboarded by those who will become episodic directors. That’s how the rules are discovered and the tone is set. Afterward, episodic directors report to the Supervising Director with their individual shows. In this case, our supervisor Audu Paden directed both parts of the opening story. My memory’s a bit hazy, but I’m fairly certain I storyboarded the climax of this one, from 17:45 to the end.

See more info at the Godzilla Fandom Wiki

Episode 2: New Family, part 2

Aired 9/19/98

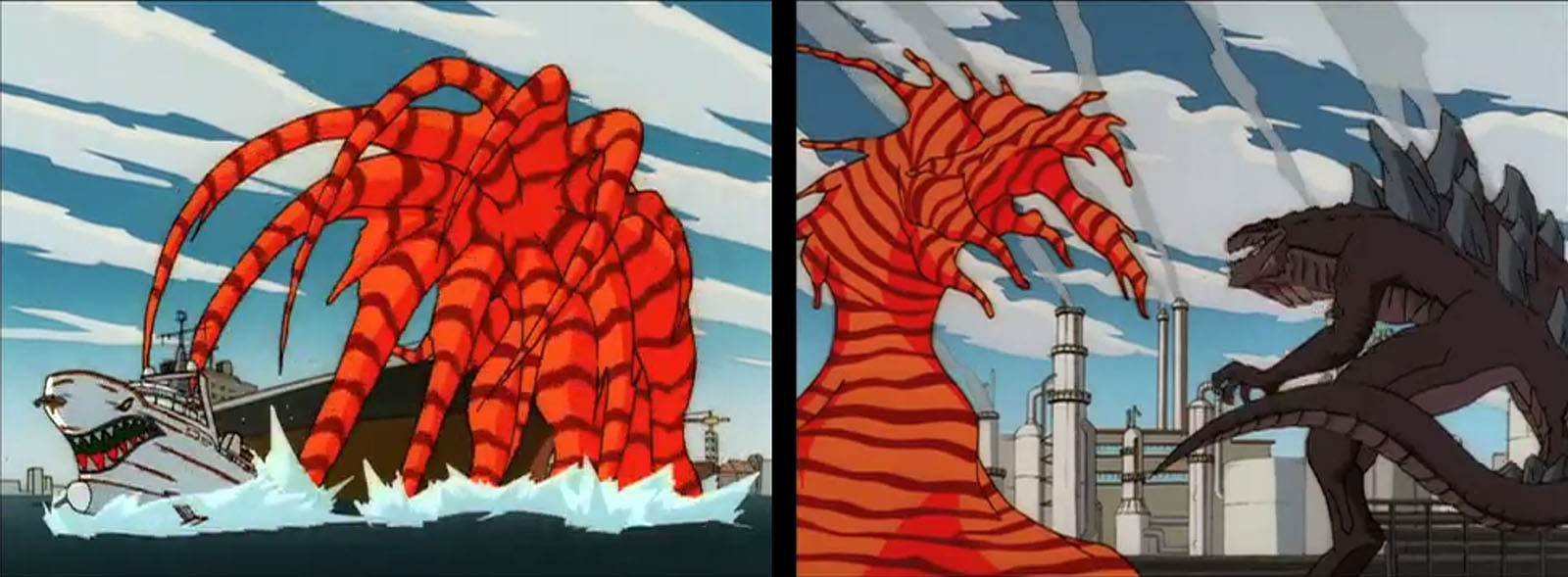

With Godzilla seemingly dead, the team journeys to Jamaica to help the U.S. military investigate the ongoing disappearances. They discover that a group of giant squids and a hideous mutant crustacean — Crustaceous Rex — are responsible. Godzilla, who survived the military attack, arrives to fight the beast off. Nick convinces Major Hicks that Godzilla is more useful alive than dead.

I think I storyboarded the climax of the monster fight, starting from 17:30. I’d be more confident about this if I’d saved any of my work from the show, but I didn’t have storage space for it at the time and was convinced that I’d always have access to it at work. Dummy.

See more info at the Godzilla Fandom Wiki

Episode 5: Talkin’ Trash

Aired 10/10/98

In response to a sanitation workers’ strike, a colony of petroleum-eating microbes controlled by nanotechnology are released to try and curb New York’s garbage problem. Unfortunately, the microbes quickly grow out of control and now the team and Godzilla must find a way to stop them before they devour Manhattan.

I had a sharp storyboard team on this show, with whom I divided and conquered the script. A lot of my time was spent designing the different stages of the creature, which was an amorphous blob that kept evolving. That’s always a tricky prospect. On one hand, you don’t have to worry too much about it being off-model, but on the other it’s constantly in motion and demanding a lot of drawing time. Every episode is a balancing act. The more animation you ask for, the harder it becomes to maintain quality. It’s pretty incredible what we asked for and actually got on our TV budget.

See more info at the Godzilla Fandom Wiki

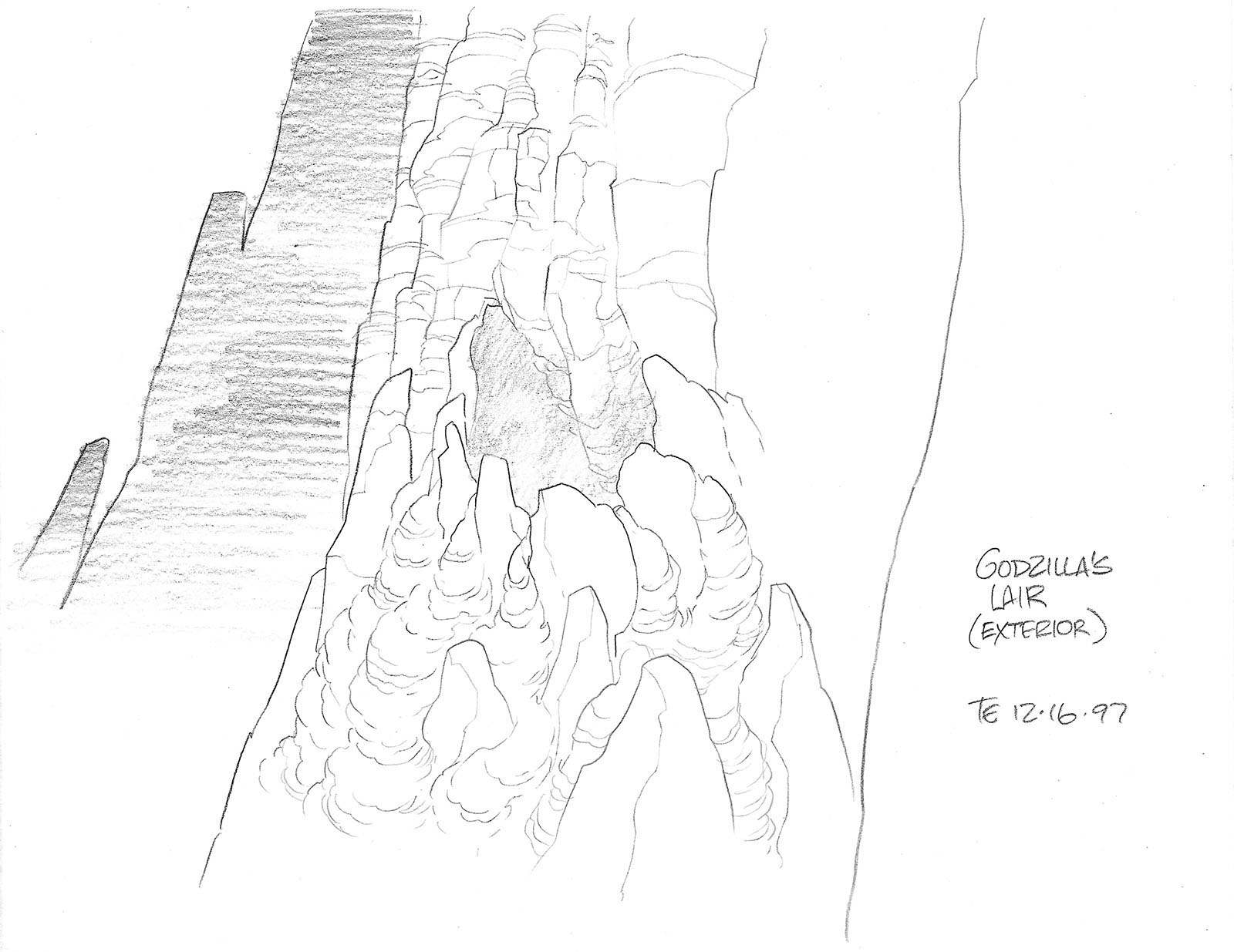

Episode 8: Leviathan

Aired 11/14/98

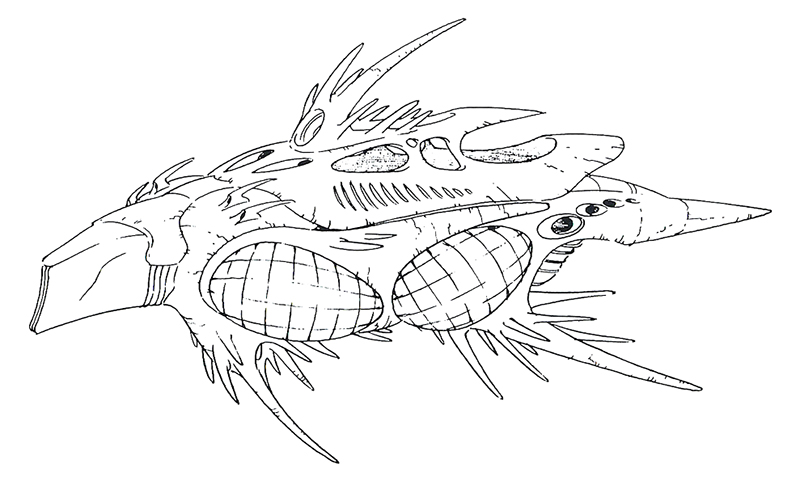

The team is called to help a rescue mission for a xenobiologist who disappeared while on a mission to explore the Leviathan, an alien spacecraft buried at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean for 65 million years. But the team discovers that the ship’s alien crew is very much alive…and they have plans for Earth.

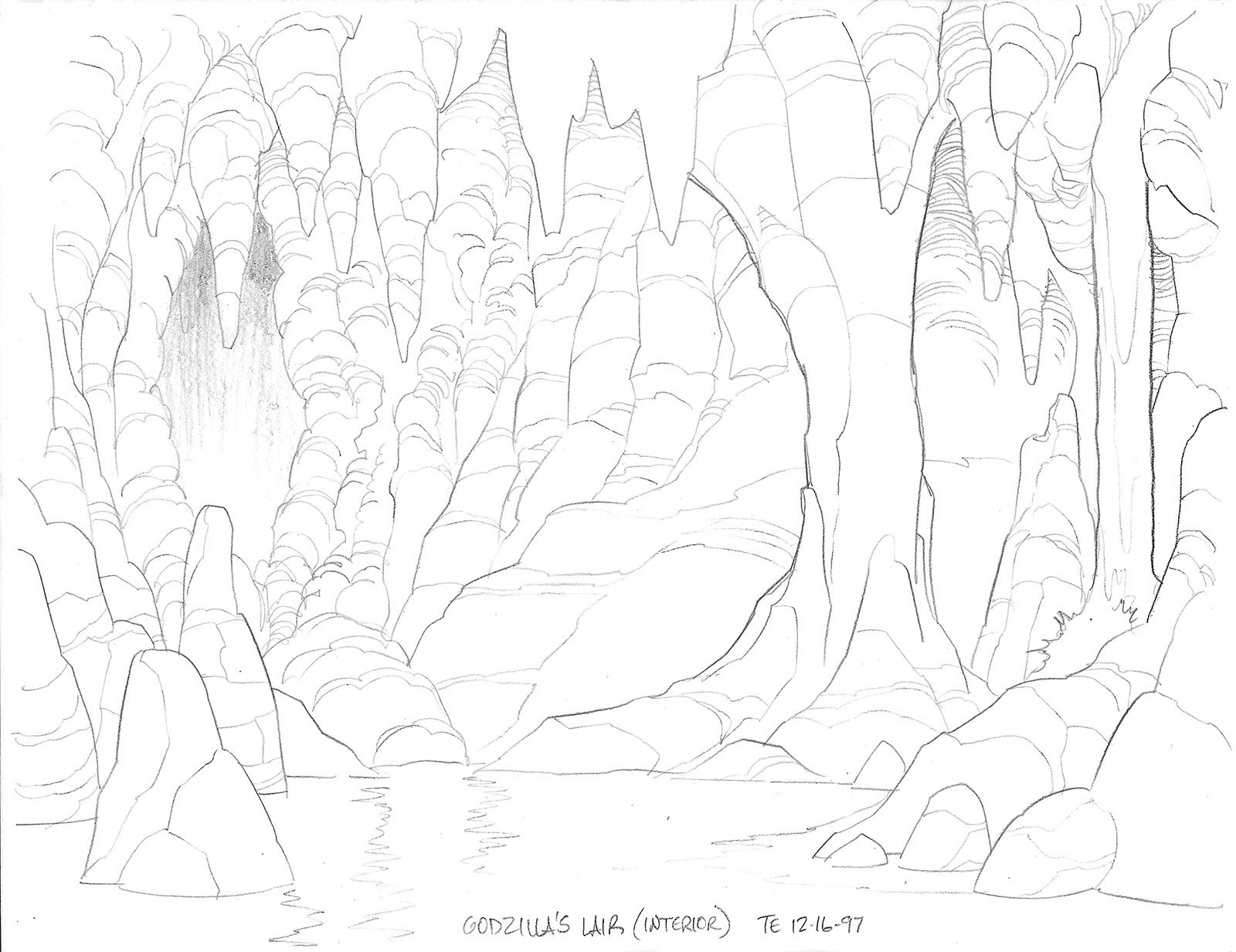

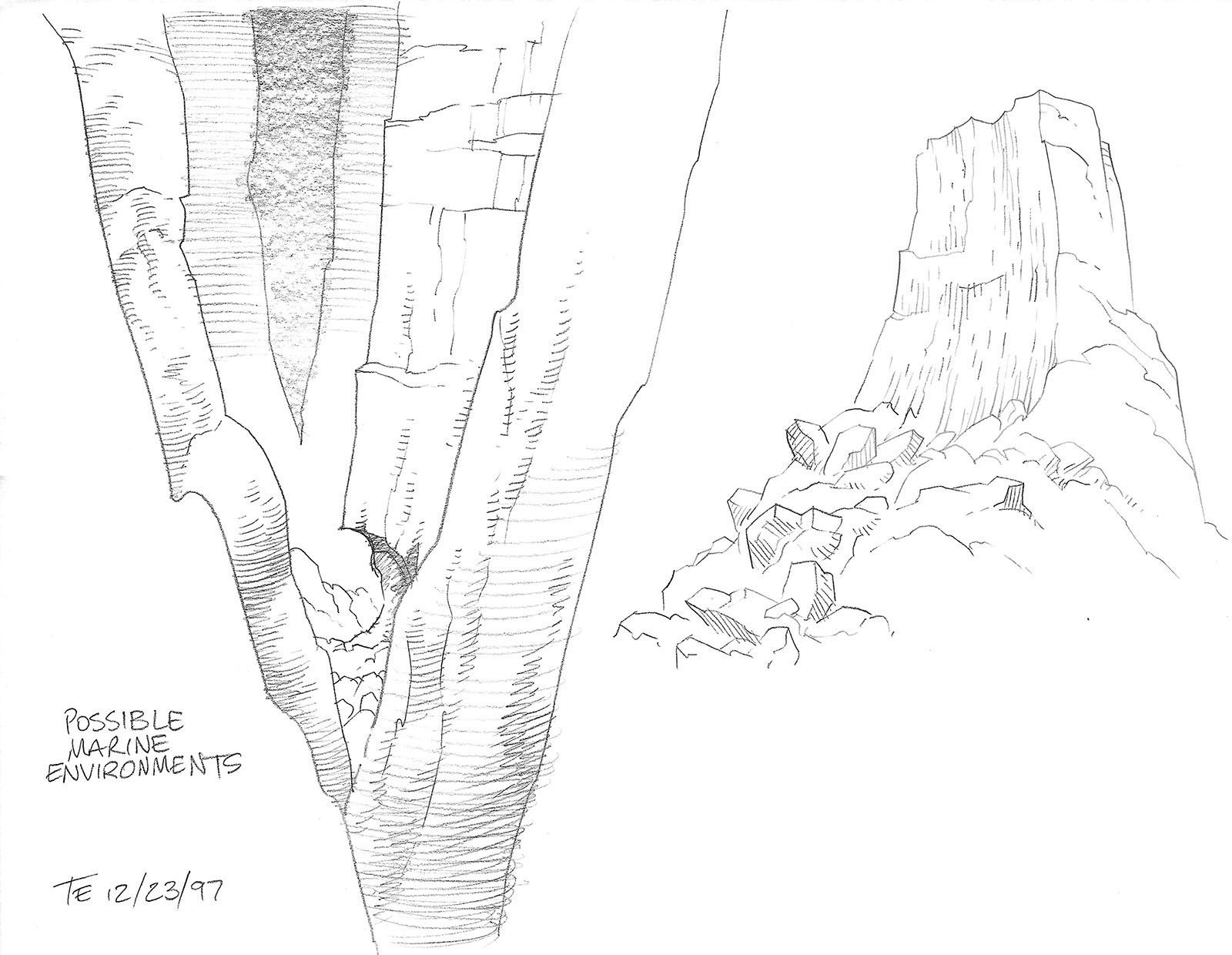

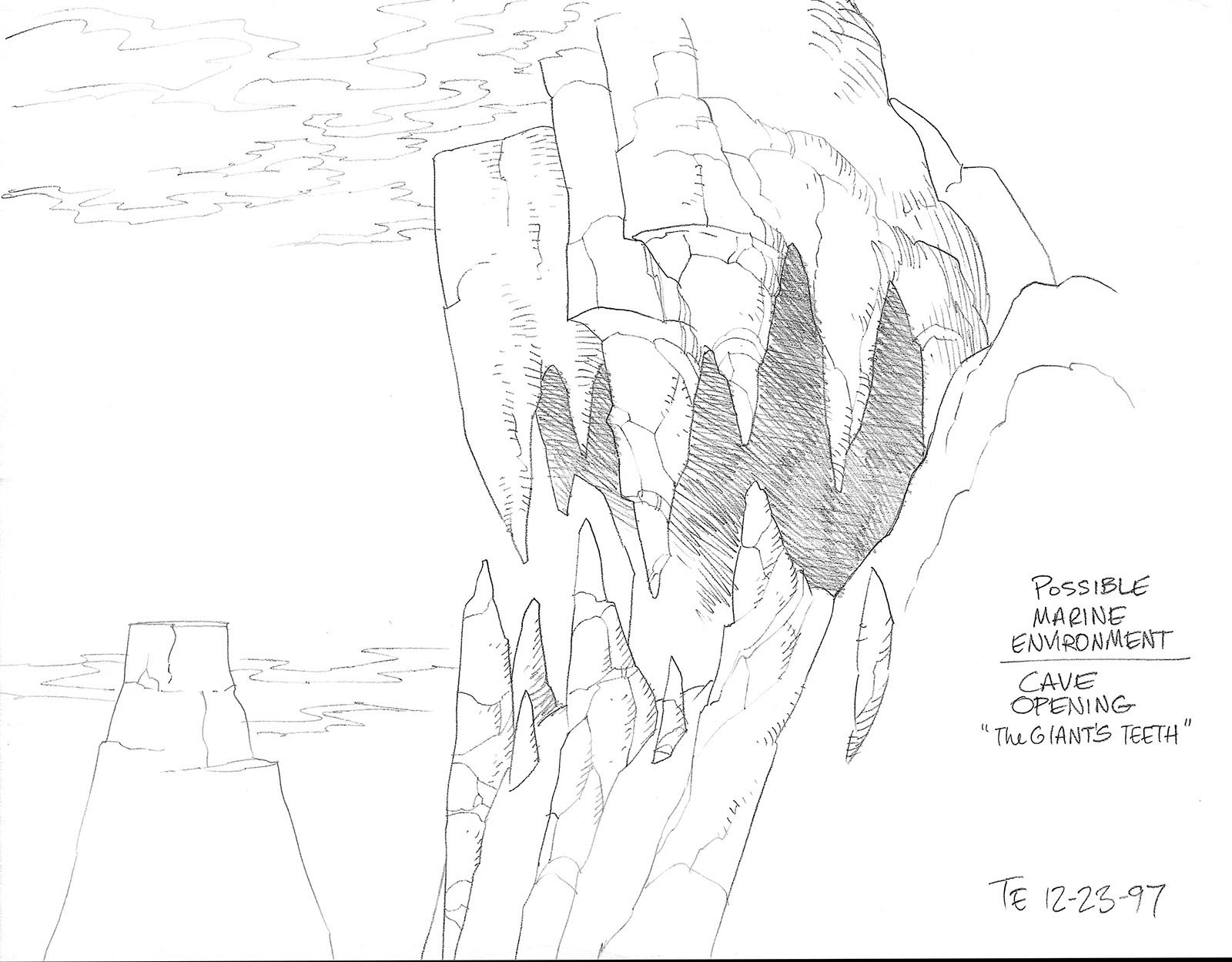

This was the last episode I worked on before I transferred over to supervise Dragon Tales, and it turned into quite an exit. Not only did I storyboard the entire episode myself (with cleanup help from seven other artists), I also designed the alien ship and all of its interiors, where most of the episode takes place. That’s about as close as you can get to a solo act in this business. And the design team certainly didn’t complain about having less work to do, so everybody won.

See more info at the Godzilla Fandom Wiki

My design for the Leviathan

Here’s photographic evidence that I actually got to attend a voice recording for the Leviathan episode. (Directors don’t often get invited, which is pretty dumb.) That’s me on the far right. I’m not smiling because I was given the wrong address to the recording studio and fighting L.A. traffic makes me very, very crabby.

1. Rino Romano (voice of Randy) 2. Sue Blu (voice director) 3. Charity James (voice of Elsie) 4. Marty Eisenberg (writer) 5. Malcolm Danare (voice of Mendel, was also in the movie) 6. Audu Paden (Producer, my boss) 7. Robert Skir (writer) 8. Brigitte Bako (voice of Monique) 9. Ian Ziering (voice of Nick) 10. Ron Perlman (guest voice) 11. Kenneth Mars (guest voice)

Unused design work

Although I did a lot of designing for the show, I only saved the four images shown below.

Bonus: Godzilla essay

In 2003, someone was preparing an academic book featuring essays on the Godzilla series and put out a call for contributions. I submitted this one and never heard back from them. ArtValt to the rescue…

The Power Thing

Much has been written over the years about the Godzilla phenomenon, about its original conception as a cautionary tale about tampering with elements beyond our control, about the dangers of nuclear power, the forces of nature shaking our illusions of control. It’s all valid and it all has relevance, but I don’t remember any of those scholarly analyses just asking a little boy why he likes Godzilla. As a former little boy myself, I can give an answer here and now: Godzilla is all about power.

When you’re young, the whole world is bigger than you are. When you’re shaken out of the egocentric world of infancy and new concepts roll into you head, one of the first things you learn is how small and helpless you are. Your immediate family is there to protect you, of course, but after a while it becomes apparent that even they aren’t omnipotent. Even they go for the umbrella in a downpour.

Something that works in your favor, though, is that while you’re insulated from the hammerblows of labor and debt, you aren’t yet required to maintain a vested interest in the mechanisms of the human world. A tornado or an earthquake can lay waste to an entire city, and as long as you’re not living there and don’t have any relatives to worry about, you’re largely free to appreciate the grand spectacle of devastation.

This, I think, is one of the keys to Godzilla’s enormous appeal. Most of us discover the big brute when we’re at that young age of helplessness and free thought, and when entire city blocks come tumbling down, we don’t have to consider the victims. Quite to the contrary, the stuff that gets broken up and smashed looks so much like our own toy collections, they bear little semblance to a container for human beings.

So what about the power thing? When I was a boy, one of my common “modes of play” was to build something and then break it. You could become intimate with the components as you built a minature structure, then you got the thrill of bringing the thing down into a magnificent heap. In that brief moment before cleanup, we get a taste of real power. We tower over the works of man, we have no use for them, they are reduced to rubble. We are Godzilla. Pretty scary, huh?

There’s a redemptive side to it, however, which comes in the form of Godzilla’s many giant opponents. As much as we boys loved seeing city blocks crushed into paste, we loved it even more when the Big G squared off against a monster that obviously had no capacity for mercy. They were often modelled on animals or invented out of whole cloth. Godzilla, at least, was human shaped, and (in many films) had big, expressive eyes that intimated a hint of compassion for the tiny humans who would be slaughtered en masse by Ghidorah, Megalon, or that giant spider. And although the atomic breath didn’t always work, it was still a long-distance weapon. The package was complete; Godzilla had it all.

With the passage of years, Godzilla movies have become more and more technically sophisticated. The newest outings freely accommodate the latest in special effects wizardry. The bouncy little self-propelled HO-scale tanks and maser cannons we remember have been replaced by heavier, more detailed, and massive counterparts. When buildings come down, they have visible structures inside them, and the smoke clouds are dense enough to block light. Godzilla doesn’t just belch a stream of radiation anymore, he aims and sweeps it with laser precision. In other words, the filmmaking toybox is a lot bigger and (consequently) more dangerous.

I wonder sometimes if the little boys of today get to have the same experience I did. Beyond all the power fantasies, there was also the delight in knowing that the adults who made Godzilla movies played with the same toys we did, and they knew what a thrill it was for us to watch them on screen, zipping around, spitting smoke, and getting stomped. I hope this isn’t being lost among the modern push for detail and realism, because in the end, the goofy effects and plastic set pieces made it all into harmless fun. I think it should stay that way.