All About Votoms

Originally written for the Armored Trooper Votoms Field Guide (Central Park Media, 2006)

Introduction

So what is it about this show? What keeps it going after twenty-plus years? What lucky charm allowed it to escape the obscurity that settled in over so many of its contemporaries? What am I even talking about?

If you’re reading these words, odds are good that you fall into the category of self-selected anime fans that look beyond the fad of the moment into the rich and storied history of this fascinating medium. I say this because Armored Trooper Votoms hasn’t qualified as a “fad” since its early days (which tends to be a good thing over the long run. Disco was a fad.) and those who are drawn to it are generally looking for more than just cheap thrills. For the sake of this essay, I’m also going to assume that you probably haven’t witnessed the slow growth of Votoms from a seminal TV series into a true multimedia colossus. If that’s the case, I envy you for the opportunity to experience it afresh.

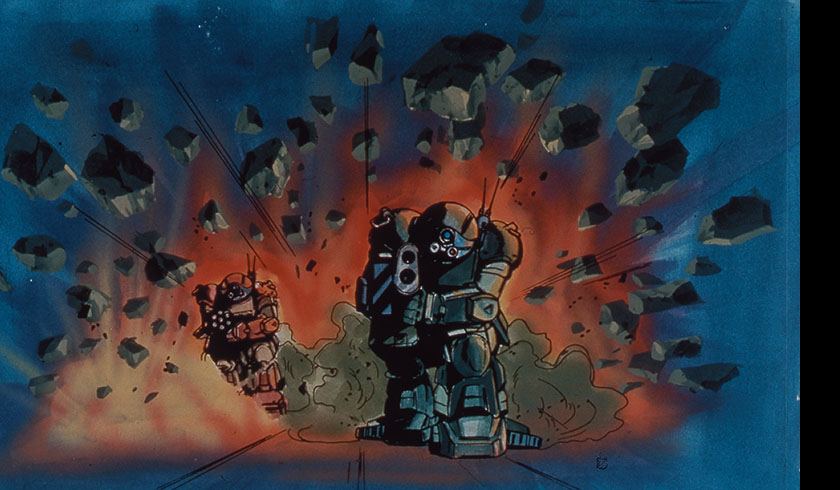

Let’s start by being honest. The series is not free of deficits. Its early-80s animation is pretty crude, its plot takes a little while to get going, and 52 episodes is kind of a lot. Compare that to most contemporary anime programs: super-slick digital/hybrid animation, lightning fast stories, and usually no more than a 26 episode commitment. Today’s anime demands much less of us. But there’s a tradeoff. Today’s anime is often hard to tell apart and doesn’t usually stay with you long after the initial viewing. Votoms, by contrast, belongs to an earlier time and, consequently, an earlier set of sensibilities.

Imagine a story with the audacity to require patience and effort from its audience! Imagine a story with many layers that unfold at their own pace, precisely calculated to reward the viewer who sticks around – eventually taking that viewer far beyond the initial premise. Those were the qualities that typified the anime programs of that earlier time, which have been around long enough now to foster an entire new generation of creators. It’s easy to tell which ones were inspired by shows like Votoms, because their work doesn’t fall into the traps I described above.

With that being said, let’s move from general to specific. What is it that makes Votoms one of the greatest anime programs ever made? Having been a fan almost since the original 1983-84 broadcast, I think I can offer a few answers.

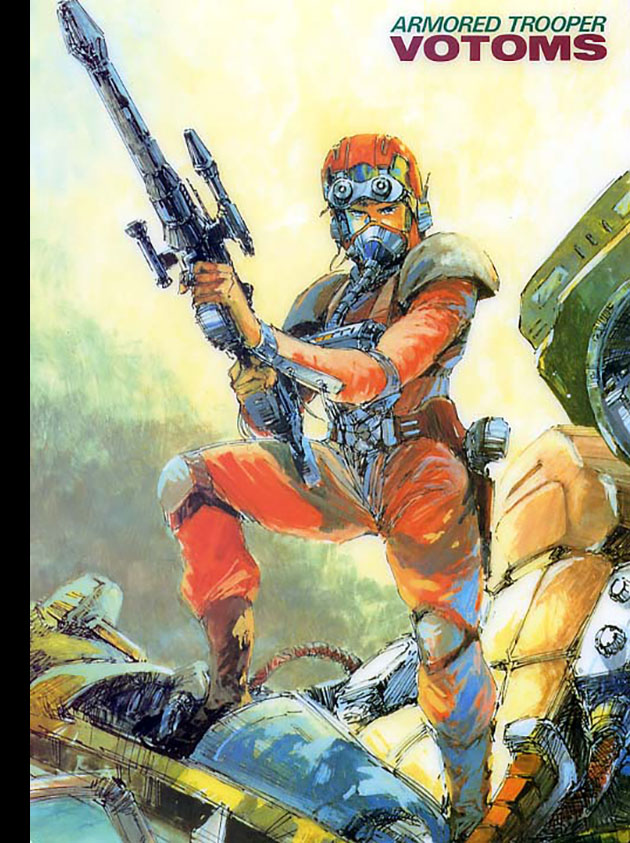

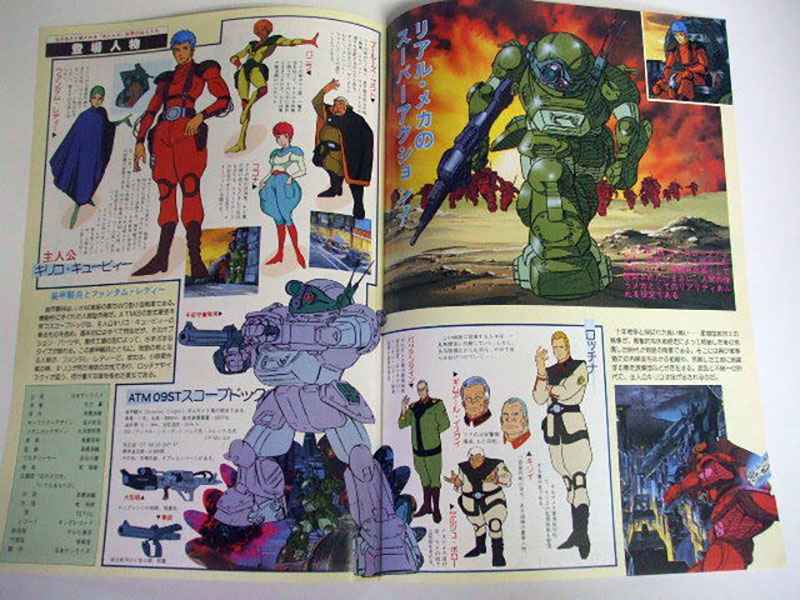

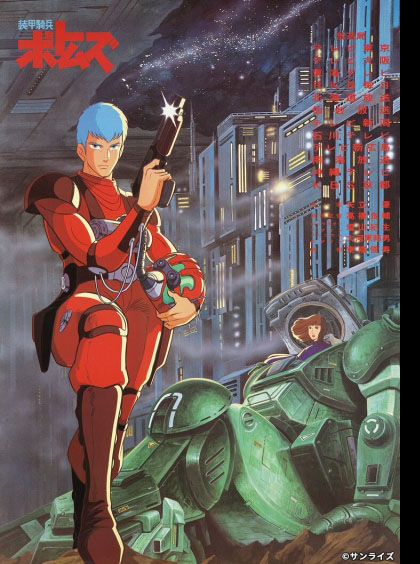

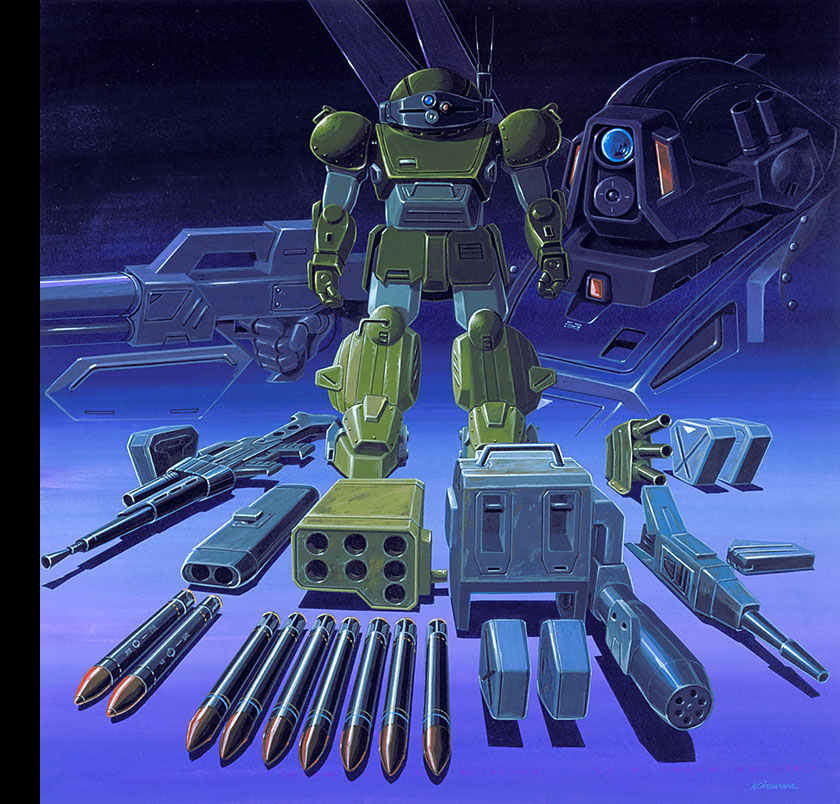

First, the quick and easy one: that Scopedog has got to be one of the coolest anime robots. Ever. A Scopedog model kit was the first brush I ever had with Votoms (back in the pre-internet days when you still had to leave your house to learn things) and it was love at first sight. And I wasn’t the only one. Even today, after 40-plus years of mecha design that seems to have explored every available niche, the Armored Trooper aesthetic still has the same appeal for the simple fact that it was designed to do just that.

In 1980, Mobile Suit Gundam began the trend of deconstructing the “super-robot” genre of the 70s into what is now called the “real robot” movement. Votoms took it a step farther, deconstructing Gundam just as thoroughly. The Scopedog is not so much designed as reduced, every piece of unnecessary flair shaved off until only the absolute minimum remains. (Ironically, both shows shared the same mecha designer: Kunio Okawara.) What is left is the most basic and unpretentious essence of the concept — a quality that perfectly represents the story it serves. With good reason, the Scopedog is still held up as a standard of excellence, seldom matched and almost never surpassed.

Once the mecha got me hooked, I started the long process of collecting the TV episodes and puzzling out the story. Believe it or not, there was a time when you couldn’t buy anime at your local store. The only way to get it was in bits and pieces, trading gnarly VHS copies with fellow buccaneers. Experiencing anime this way was like archaeology, digging through it one stratum at a time and comparing your findings. Sometimes this would lead to disappointment if your imagination outpaced what was actually there. With Votoms, this wasn’t the case.

Every time a new tape or book or data fragment rolled in, my assumptions were surpassed. Votoms was turning into a bottomless gold mine. My experience was probably not too far off from what it must have been like for Japanese viewers, who only got 22 minutes of story once a week and had no option but to wait for the next 7 days. The suspense and anticipation became part of the whole experience and made the show more endearing. Regrettably, that part gets lost when the entire thing is handed to you all in one big translated hunk.

Nevertheless, it’s always refreshing to go back to basics, and Votoms offers this opportunity with every viewing. Its creator, Ryosuke Takahashi, is a masterful storyteller, having perfected the fine art of plunging you into the deep end of the pool and slowly bringing you up to the surface. By the end of each story arc, much has been learned and accomplished, but with the very next episode you’re right back in the deep end again. This is especially true of the third arc, Deadworld Sunsa. Any other show would probably conclude with the death of the arch enemy, but Votoms has even farther to go and every detail is revealed at exactly the right pace. It’s just as entertaining to dissect Takahashi’s work in a tenth viewing as it is to see it for the first time.

Jumping backward a second to the idea of rewards being commensurate with effort, this may be a good point to provide an example. This isn’t the first time I’ve written about Votoms. I crossed that line in the late 80s, assembling all the info I had collected into a thick fanzine and sharing it with everyone who even smelled interested. This included the good people at U.S. Manga Corps, who took up the cause and actually brought the show to American audiences in the 90s. They went one better by giving me the chance to create a Votoms graphic novel and eventually asking me to write the words you’re reading now.

I heartily support the concept of rewarding great effort, and the rewards have certainly come to Ryosuke Takahashi. Previously, he had cut his teeth writing such anime classics as Cyborg 009 and Dougram, and he would go on to create others such as SPT Layzner and Gasaraki. Despite these stellar credits (and to his occasional chagrin) Votoms has proven his most enduring creation, reinforcing his legacy time and time again

How is it that a single TV series can accomplish this? No matter how well-crafted anything is, time must eventually leave it behind, right? The answer to this brings me to my next point. Votoms isn’t just a TV series. It’s a whole universe. One so vast that even 52 episodes only scratch the surface.

Removed as we Americans are from the nerve centers of anime fandom in Japan, we are left with only one reliable gauge for the lasting impact of a series: the amount of merchandising that continues to appear after its debut. By that reckoning, Votoms never actually ended. Almost immediately after the TV series went off the air, the spinoffs showed up. Model kits, soundtrack albums, books, OVAs, more books, toys, more OVAs, video games, even more books…each new contribution made the picture bigger, and the miracle was that it only got better. Unlike the Gundam universe, which has to periodically reinvent itself to avoid collapsing under its own weight, the world of Votoms is so big that it can accommodate almost any new add-on. More importantly, it can accommodate the imagination of the viewer.

The book you’re reading is assembled with all this in mind: that the odyssey of Chirico Cuvie is part of a much bigger, ongoing story. If it seems a little overwhelming, and you feel like a lot of it may have passed you by already, then consider yourself blessed. You still have the chance to experience this thing a little bit at a time.

Production Order

1. TV series, 1983-84

2. The Last Red Shoulder (OVA), 1985

3. Big Battle (OVA), 1986

4. Roots of Ambition (OVA), 1988

5. Armor Hunter Merowlink (OVA series), 1988-89

6. Shining Heresy (OVA series), 1994

7. Pailsen Files (OVA series), 2007

8. Phantom Arc (OVA series), 2010

9. Case Irvine (OVA), 2010

10. Votoms Finder (OVA, alternate universe), 2010

11. Alone Again/Chirico’s Return (OVA), 2011

Viewing Order

1. Roots of Ambition (OVA)

2. Pailsen Files (OVA series)

3. Uoodo (TV series, first arc)

4. The Last Red Shoulder (OVA)

5. Kummen/Sunsa/Quent (TV series)

8. Big Battle (OVA)

9. Shining Heresy (OVA series)

10. Alone Again/Chirico’s Return (OVA)

11. Phantom Arc (OVA series)

Side stories (no specific order)

1. Armor Hunter Merowlink (OVA series)

2. Case Irvine (OVA)

3. Votoms Finder (OVA, alternate universe)

The Making of Votoms

It was 1982, the early phase of post-Mobile Suit Gundam robot anime. Having delivered a genuine hit and turned the genre on its head, Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino was now the pre-eminent writer/producer at Japan’s upstart Nippon Sunrise Studio (later to be renamed simply “Sunrise”). Thanks to him, the reign of the 70s-era “super robots” was fading, and the “real robots” were taking over. While Tomino produced his next two groundbreaking programs, Legendary God Giant Ideon (1981) and Battle Mecha Xabungle (1982), another writer/producer named Ryosuke Takahashi was hot on his heels.

Well known for his previous work, which included Sunrise’s Cyborg 009 TV series (1979), Takahashi had delivered his own successful “real robot” entry to Sunrise, Fang of the Sun Dougram (1981). He was anxious to make his next project a fantasy adventure, but Tomino beat him to the punch when he started to develop yet another series called Aura Battler Dunbine (1983). This curious bit of timing pushed Takahashi into an entirely different direction, one of those uncharted creative paths that change peoples’ lives.

“When a soldier who only ever lived in the battlefield is suddenly dropped into civilian society at the end of a war,” Takahashi thought, “he would be an imperfect citizen. In a peaceful world, even an excellent soldier would be challenged on a spiritual level to fit in.”

This became the foundation for his new project, to be called Armored Trooper Votoms. Naturally, much more work was required to build it into a complete story.

“Originally I didn’t have any thought of Wiseman or the Secret Society,” Takahashi explains. “Instead of having A.T. pilots try to make a living running around in Scopedogs after the war, I imagined them being used in an entertainment arena, kind of like pro wrestling. I got that idea after watching a Steve McQueen movie (Junior Bonner, 1972) where he played a traveling rodeo star competing with others in his field. Also, I wanted to capture the mood of Apocalypse Now.”

Other writers came on board to help move the concept forward, including Toshi Gobu, a veteran of an earlier Takahashi series, Zerotester (1973), and Tomino’s Xabungle.

“Mr. Takahashi was going to create this fantasy tale, and I thought, ‘cool.’ Then the story got redirected and Votoms gradually began taking shape. Basically it’s a tale of a soldier who is forced to rehabilitate into a civilian life. There have been many stories about what a character does on the battlefield, but this was the first one where we dealt with the aftermath. This is what made the project so interesting. Chirico is somewhat deficient when it comes to social skills and societal values, and we wanted to explore how he deals with that.”

Another of Takahashi’s trusted collaborators was Dougram’s character designer Soji Yoshikawa, who was ready to earn his stripes as a writer. Naturally, he was a participant from the very beginning.

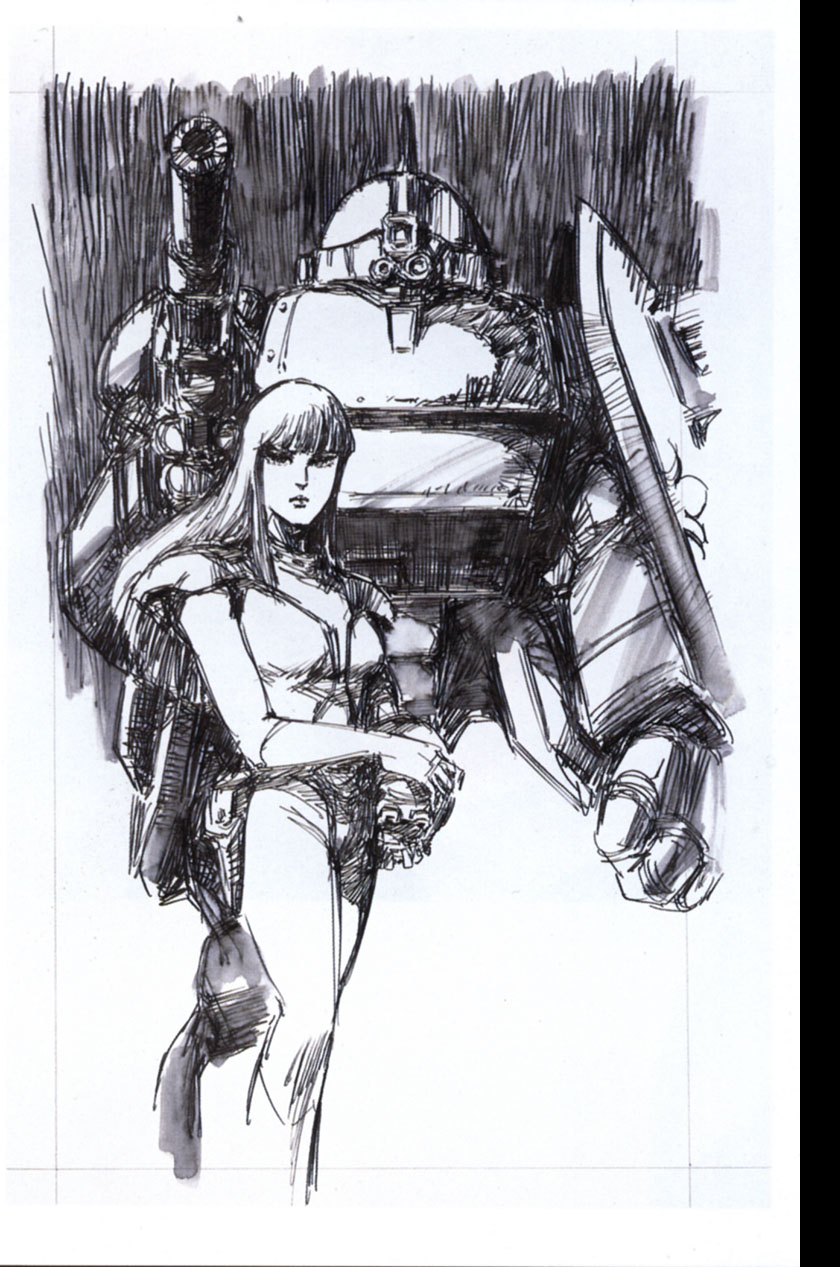

“If you saw some naked woman appear out of nowhere, you’d be like, ‘what the–?’ Takahashi mentioned Blade Runner, so I wondered if that woman was something like a replicant. This propelled our discussions forward, and her initial scene became very important. Somehow it all came together quite naturally.”

The third and last writer, Jinzo Toriumi, came in with an eclectic set of credentials including Gatchaman (1972) and Time Bokan (1975).

“I joined just as they were writing the first script. Mr. Takahashi would say he wanted it to go this way or that, and we would have meetings to discuss all the details. I had some concerns about the complexity of the project because it was animation, and there would be children watching.”

For purely commercial reasons, the series would also have to include the all-important giant robots and here too Takahashi wanted to explore new ground. With mecha on everyone’s mind at Sunrise, some began to wonder if they fully grasped the implications, and whether a human was actually capable of operating a robot. This was a sobering question for a new studio that had made robot-oriented anime its bread & butter, and it had a definite impact on Soji Yoshikawa.

“This was something we needed to consider for the Perfect Soldier. I was focused on the occult, since using mind control on robots was an issue we discussed nearly every day. But we couldn’t go that route in a commercial TV series. Instead, the P.S. seemed to be some kind of super hero. I was basically in charge of the concepts for the show, so the decisions about controlling the robots came down to me in the end.”

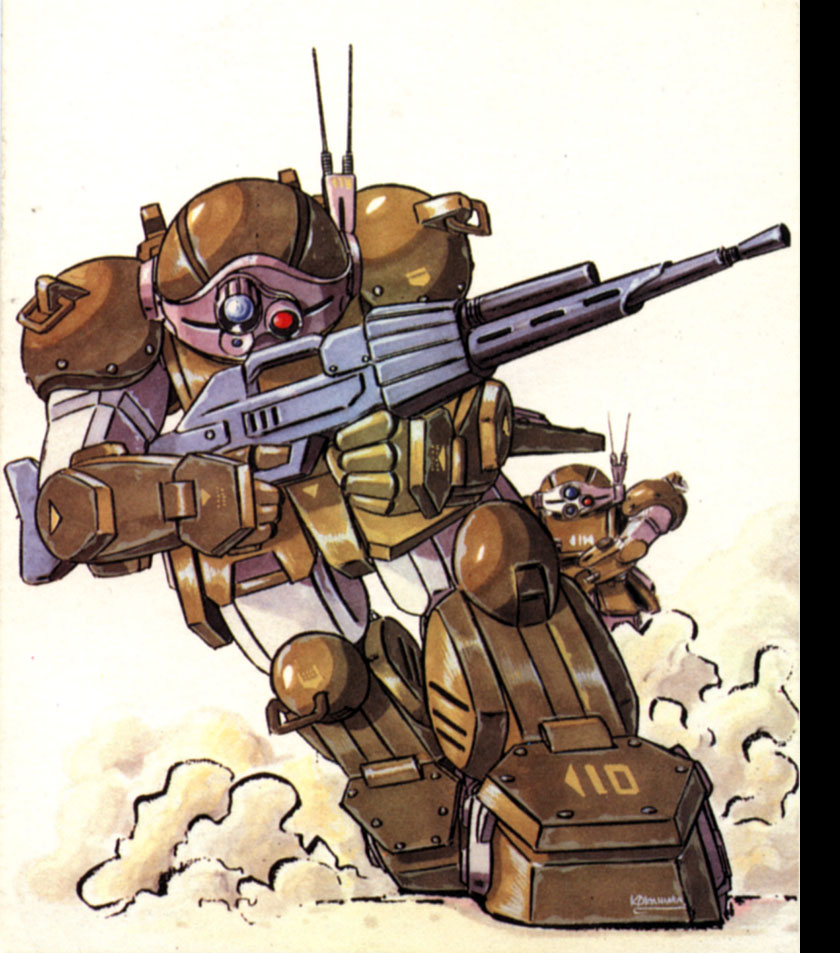

Fortunately for Yoshikawa and the others, an expert was already in their midst: Kunio Okawara, whose mecha-design genius had graced every one of Sunrise’s recent hits, including Dougram. Independently, Okawara had already set goals for his next set of designs that would perfectly suit Votoms.

“First,” Okawara explains, “when we would eventually produce the toys and model kits, they had to pose exactly as designed without modification. Second, I wanted to do something smaller than the Dougram robots, which I felt were too large. Third, it had to look as if it could be made in a factory of today.”

It was, in fact, an unexpected twist in the design work for Dougram that set the stage for what was to follow.

“We had problems figuring out the ‘relaxed’ pose of the robots, because the joints would not work in that position. I made a mockup model of this pose and showed it to Mr. Takahashi just around the time Votoms was starting up.”

When Takahashi saw the mockup, he wondered what might happen if “giant robots” were made a little less “giant.” At his request, Okawara put a miniature pilot in the mockup, got it to look right, and calculated the scale in reverse.

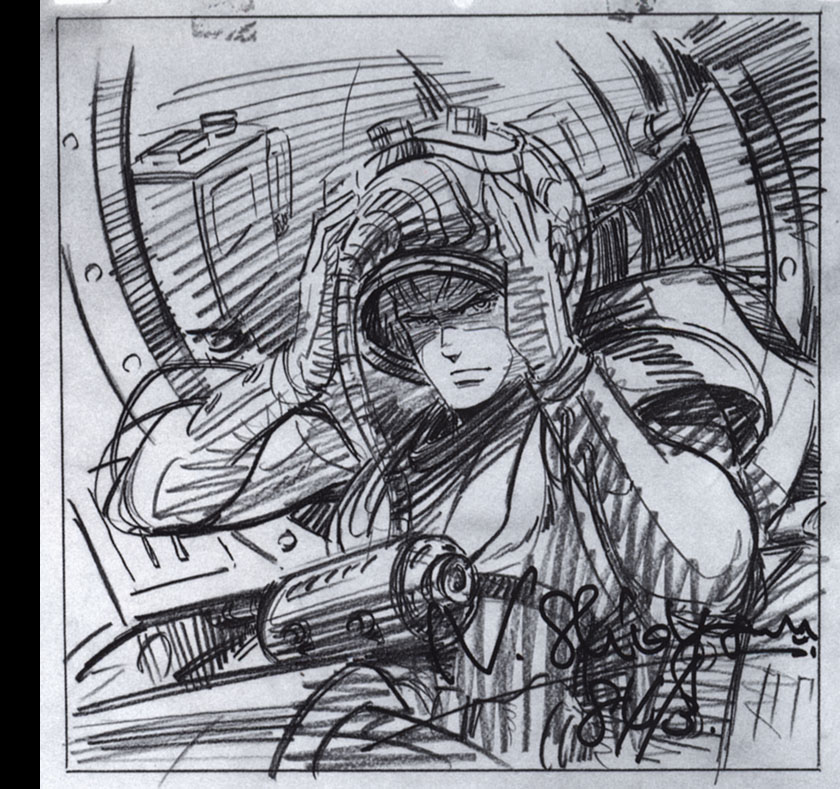

“The robot came out to 4 meters tall, which would look awesome on screen. Mr. Takahashi wanted a multipurpose robot, and a 10-meter frame just had too many limitations. Besides, it’s more dramatic for a person to leap into a cockpit, so we decided to go with the reduced size. Anything smaller than 4 meters, and you’re in the realm of powered suits.”

This shift in thinking brought a whole new set of physics into play now that the robots would have to interact with human-scale vehicles rather than enemies the size of office buildings.

“Mr. Takahashi was good at identifying what needed to be done with a design. He’d say this should be added or that should be changed, developing things like the rollerdash or the arm punch or the turnpick. He wasn’t as concerned about the overall design as he was with function. The idea for the lens turrets came from him, Norio Shioyama, and others.”

At 4 meters, Okawara’s Armored Troopers still hold the record for the smallest of anime’s “giant” robots. Although large robots are more powerful, it’s hard to keep a sense of scale between them and their human pilots. By reducing this scale to what we’re familiar with, it’s easier to gauge the size of a Scopedog and visualize a person sitting inside. From there, it’s even easier to realize how vulnerable that person would be, which enhances both the excitement and the realism. The tight fit, minimal protection, and limited connection to the outside world make the experience of a pilot even more vivid for the viewer.

“Without the proper training,” Okawara continues, “you couldn’t ride in that cockpit. It’s a very small space, so we had to figure out how best to utilize it. A claustrophobe would go crazy in there.”

Every aspect of the A.T. was thought through to its fullest extent, including the flexibility to use it up and throw it away. It was and still is anime’s first fully disposable robot.

“The mecha for Votoms were designed primarily to avoid complicated details and extra work. I had drawn a number of conceptual sketches for others to build on, but they didn’t come up with many alternatives. The Berserga class was a novel touch, but it’s an older model. Toshifumi Takizawa did come up with the smaller Zwerg, however.”

Takizawa was another of the masterminds that fed fresh ideas into the series, serving as an experienced director and designer under Yoshiyuki Tomino on Ideon and Xabungle.

“Votoms focused on a narrow adult audience,” Takizawa says, “and since we didn’t have to cater to a wider one, we had free reign over what we wanted to put in without having to worry if everybody understood everything.”

“Instead of a simple, clear-cut setting, we began with dark, scummy, mafia-type lowlifes scurrying in trash-strewn streets as our basic image of the world. The scenery and mood would change as the story developed. At least that was what we originally intended. But looking back on it now, the visuals tended to take on a life of their own, and, like Chirico, survived through all our attempts to change them.”

“When the A.T.s fought, we wanted to show as much physical interaction between the pilots as possible. But this was complicated by the fact that we couldn’t show their faces. We did the best we could by switching the viewpoints often.”

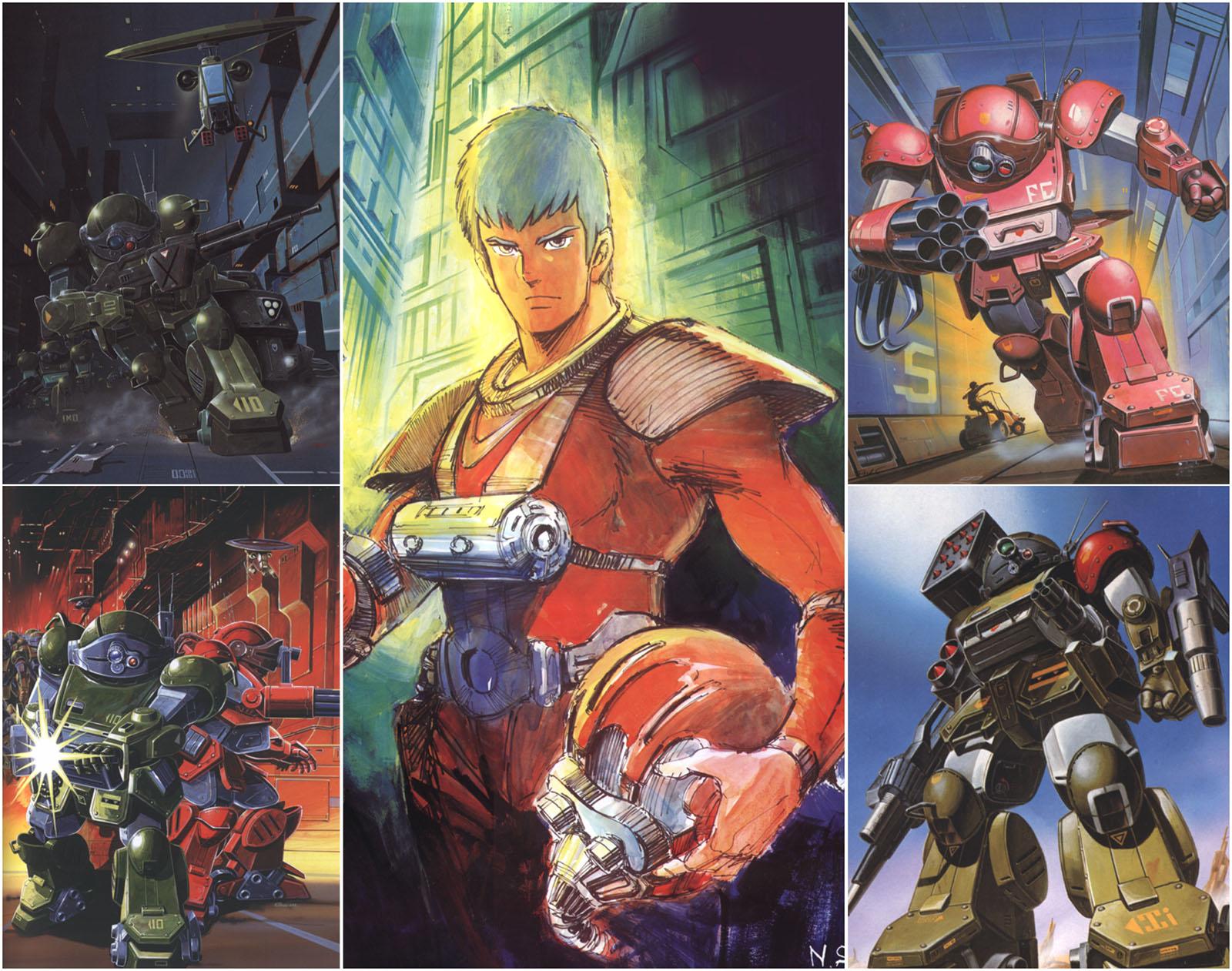

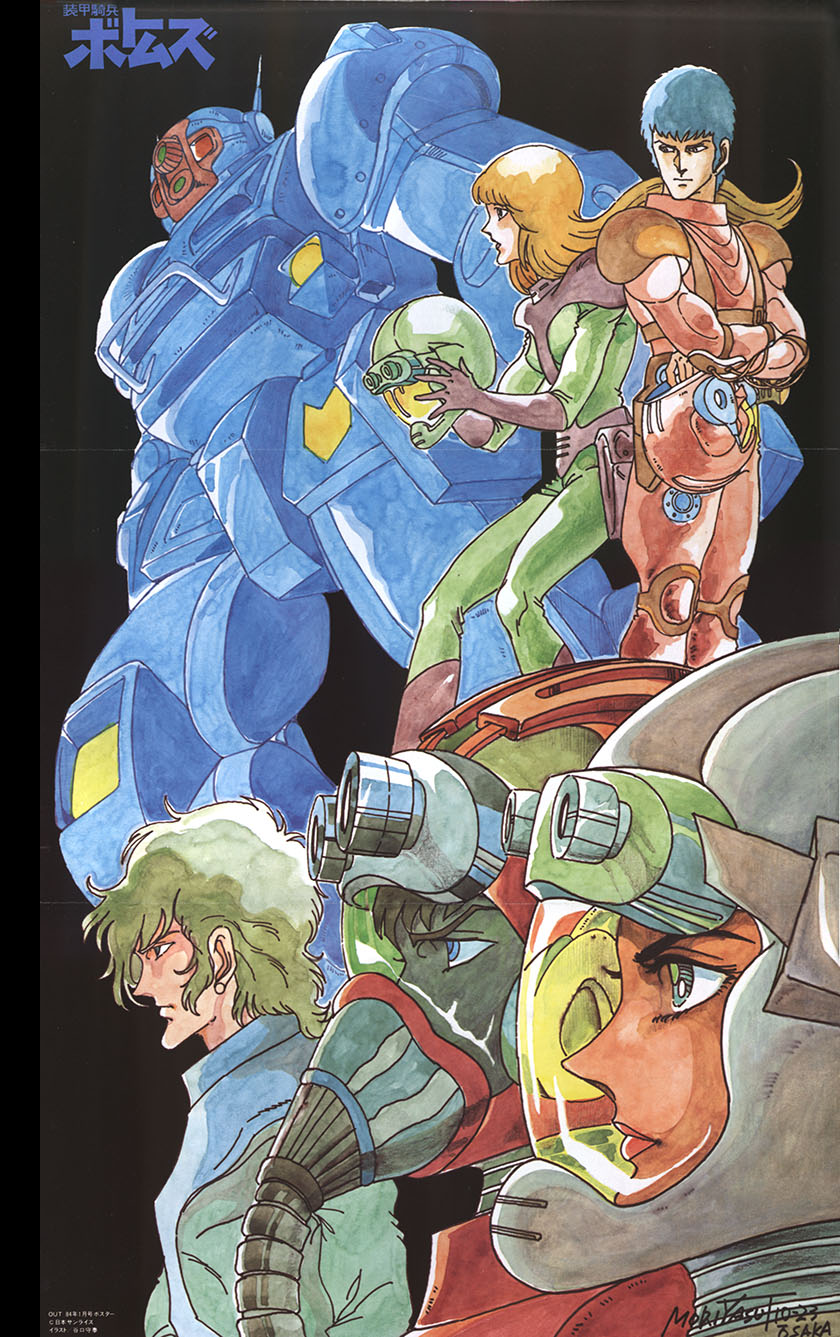

Another contributor was equally vital to the series: Character Designer Norio Shioyama. Having served as Soji Yoshikawa’s assistant on Dougram, Shioyama was given the task of designing the Votoms characters on his own. From the beginning, he wanted Chirico’s look to match his attitude.

“I first imagined Chirico as a boy whose mind was damaged by the war. As he met many people and experienced many things, the wound would be healed.”

Simultaneously, the look of the character would soften as the series progressed. As the story evolved, however, it was decided to start Chirico out with a more mature look to help differentiate him from more severe and excitable characters, such as Vanilla and Coconna.

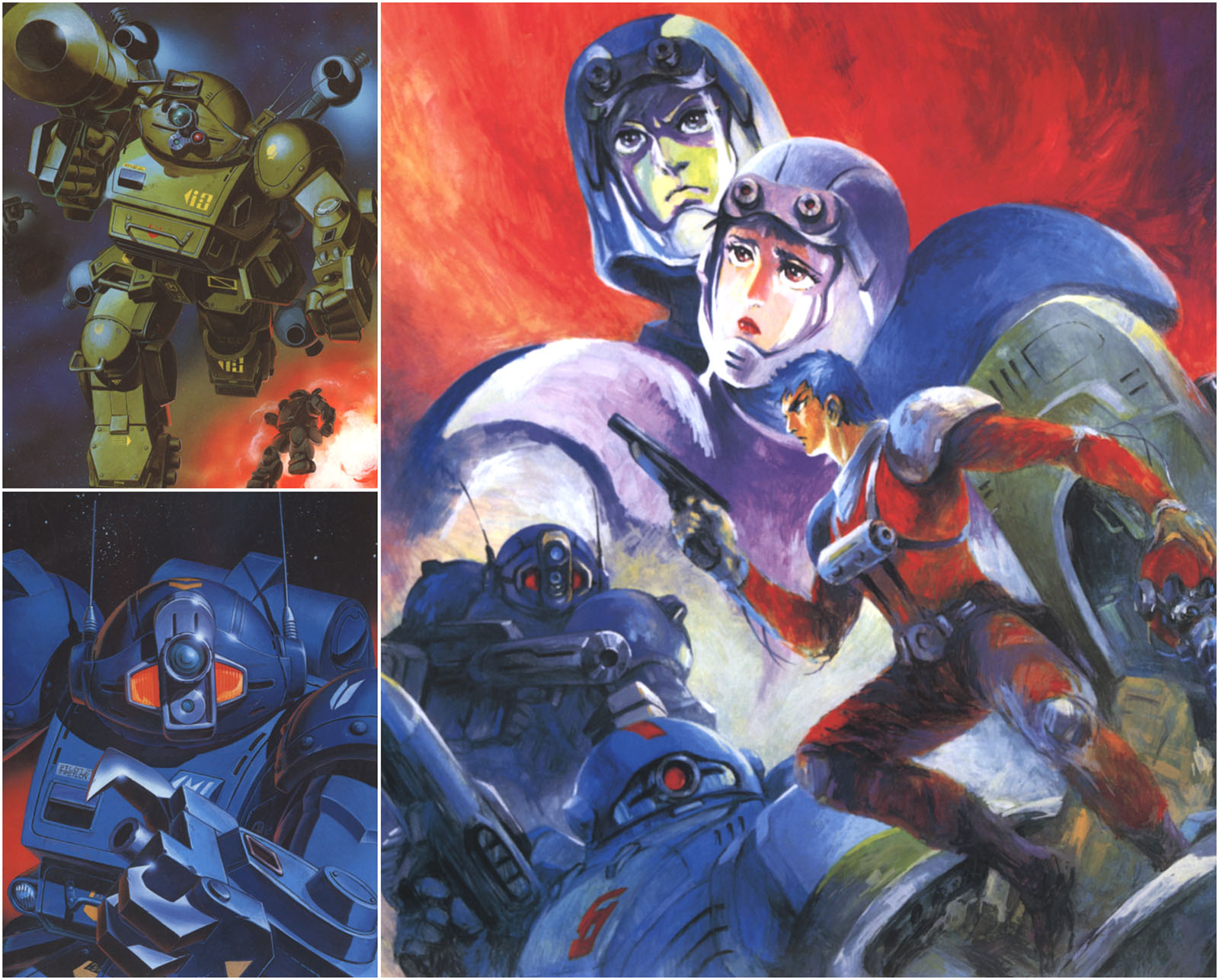

Fyana, on the other hand, required a different approach. Shioyama wanted her P.S. nature to set her above ordinary humans, so he originally envisioned her as a holy figure. As she was written into more and more action scenes, it became necessary to toughen her up for practical reasons, but the original concept is still apparent, especially in the early episodes.

Production economics later demanded that Shioyama share key character animation duties with Moriyasu Taniguchi, whose angular style would later grace another Takahashi program called SPT Layzner (1986), but the enduring image of Chirico is pure Shioyama.

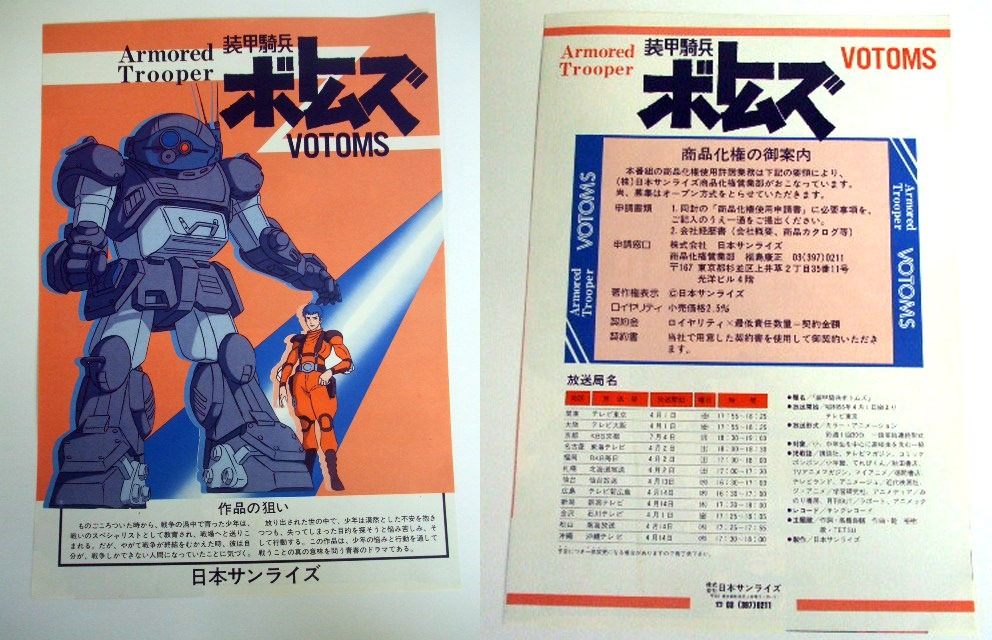

Votoms was broadcast on Japanese television from April 1983 to April 1984. Its ratings were not phenomenal at the time, but its popularity exploded over the following years, backing up the assertion that it was a series ahead of its time. Part of the reason for its latent success was the meticulous planning that went into the program from the beginning, especially when the limitations of the television medium were confronted.

“At the time, we figured the show would take off,” said Takahashi, “but TV shows have a bad habit of getting canceled at a moment’s notice, so we separated the series into four stages, with a break between each part, in the event that this actually happened to Votoms. This also left gaps that gave us the opportunity for future stories.”

During the series, and to an even greater degree in the spinoff stories, the staff evolved Chirico’s character from deep observations of war and its impact on the individual. They had begun to explore this in Dougram, but later agreed that the viewpoint of that series was too broad and the characters not strong enough.

“There will be war,” Takahashi said, “as long as there is a tendency in people to either rule or be ruled over. In Votoms, the camera is more intimate and concentrated on the hero. I wanted him to have a strong personality, but refuse to rule or be ruled over.”

The result of this thinking was a truly original character. Chirico walks a path between opposite extremes. He is given the options to either be dominated by others or use his power over other them, and he chooses neither. Writing for such a character was an unusual challenge for Jinzo Toriumi.

“Chirico is not a sociable character, and even though I thought I had limited his dialogue as much as possible, Mr. Takahashi said it was still too much. I went back for another look, and he was right. Chirico did talk quite a bit in the original script.”

As the story progressed, the writers found Chirico’s character too strong to remain bound to one place, so as locales changed, the focus of the story changed with it. This presented an unforeseen challenge: what would be a proper ending to Chirico’s story?

“We didn’t have the ending planned at first,” said Jinzo Toriumi, “but we knew where the story was headed. Chirico had become too powerful, so we ended up having him become God’s chosen one since we didn’t want to invent a new race of people for him to belong to. We should have added more scenes between Chirico and Fyana to show their love for each other, now that I think of this.”

“Creating an original robot anime wasn’t easy,” added Toshi Gobu. “The storyline didn’t form smoothly, and we had to consider what Chirico would do when his sole purpose in life, to survive on the battlefield, was suddenly taken away. I think Mr. Takahashi brought ‘God’ into the storyline as Chirico’s salvation. That allowed us to clear up some loose ends, as well as giving Chirico a new purpose. Revealing that everyone was manipulated by God allowed us to show Chirico as an even greater victim of his environment and circumstances.”

This particular plot twist is thought to have been inspired by Arthur C. Clarke’s The Nine Billion Names of God (1952) in which a computer is assigned the task of quantifying divinity. Around this basic premise, Takahashi conceived Planet Quent, to which Chirico travels in the final stage of the series.

Integrating the Quent story required an enormous effort from the writers as they constructed thousands of years of galactic history. Most of this information didn’t make it into the TV series and was revealed later in print. The fact that the story went far beyond its initial premise fueled a franchise that shows no sign of abating more than 20 years later.

Takahashi and his collaborators went on to create many other successful anime programs. And though most of them are active today, they still consider Votoms to be their masterpiece.

“I tried to make our job as simple as possible,” remembers Kunio Okawara. “I don’t have the knack for “cool” robots, so mine end up kind of dumpy looking, like the Scopedogs. Until recently, they never appeared elegant since they look like something that might actually become a reality.”

Soji Yoshikawa is fond of the science fiction aspects:

“A story like this is quite unusual, and topics about human neuroscience are fairly interesting. Because it was to be a dramatic presentation, we couldn’t focus too heavily on such science, but the fact that we were able to add anything at all made the show more interesting.”

For Jinzo Toriumi, it was a rare chance to satisfy his own creative urges:

“I like writing scenes that catch people off guard, twisting the plot to give it a more mature feel. For example, rather than having a woman run toward a man to express her love, as is usually expected, I’d rather have her run to cover him from enemy fire. Or a scene where someone suddenly throws bags of money out of a helicopter. That was one of my favorites.”

“Votoms is not a flashy anime for kids. It has many levels that adults can enjoy as well. I think Votoms fans are true anime fans.”

With characteristic brevity, writer Toshi Gobu concurs:

“I like Votoms because I was able to create things as I saw fit. I believe Chirico’s fans have continued to show interest in him because there is something about the character that they can personally relate to in their own lives.”

And despite the circumstances that drove the project away from the realm of fantasy, Ryosuke Takahashi still found a way to satisfy his original aim:

“Although Votoms shows a realistic vision of robots, the story is still a fantasy to me. The ending is happy and somewhat unrealistic, like a fairy tale. I couldn’t imagine Chirico settling down and raising a family, nor did I want to see Fyana die, or have them separated again, since that was already done. So I figure the series ended where it should have, even if we add other tales at some later time.”

Fortunately for all of us, those tales are still being told.

Quoted text comes from a Votoms book published in 1987 by Animate. Translations by Earnest Migaki.