Series profile: Space Brothers

When I think about Space Brothers, I get angry. I’ll explain why in a bit. First I have to tell you how great it is.

If you’re like me (and I know I am), you watch every astronaut movie you can get your hands on, and afterward you think, “I wish someone could give us a version of that that lasts longer than two hours.” I’ve got good news for you: a Japanese fella named Chuya Koyama has been doing exactly that since 2007. And he’s still at it as I write this.

The story begins in Japan in the year 2006. Mutta Nanba (12) and his brother Hibito (9) witness what they think is a UFO flying toward the moon. Hibito decides on the spot that he wants to become an astronaut, and Mutta promises that he will, too.

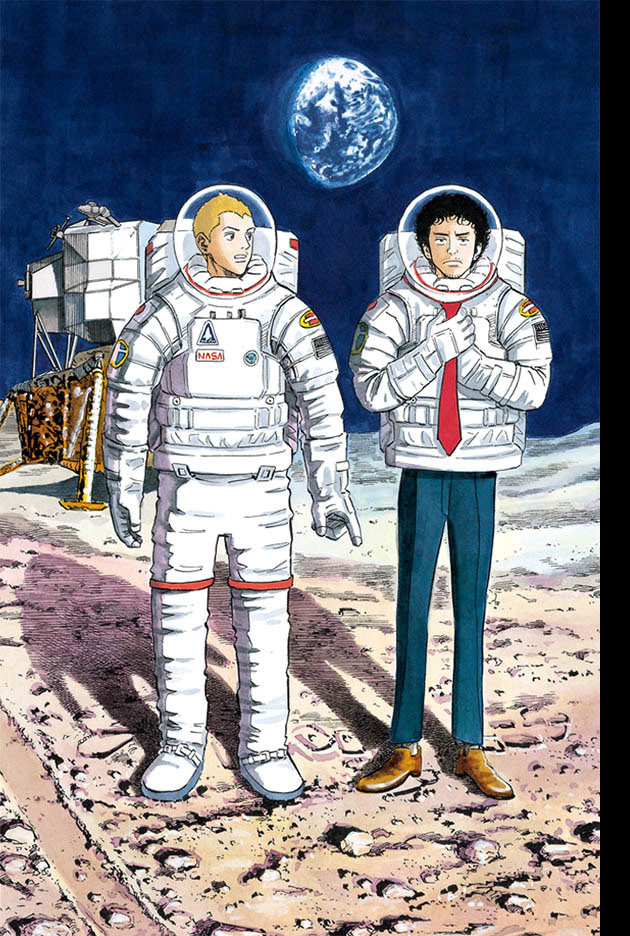

Then we jump forward to the distant year 2025. Hibito is soon to make history as the first Japanese astronaut on the moon while Mutta, having failed to keep his promise, gets fired from his job at an auto engineering company. With his life at a nadir, Mutta receives a phone call from Hibito which reignites his childhood dream. This is where the story really begins.

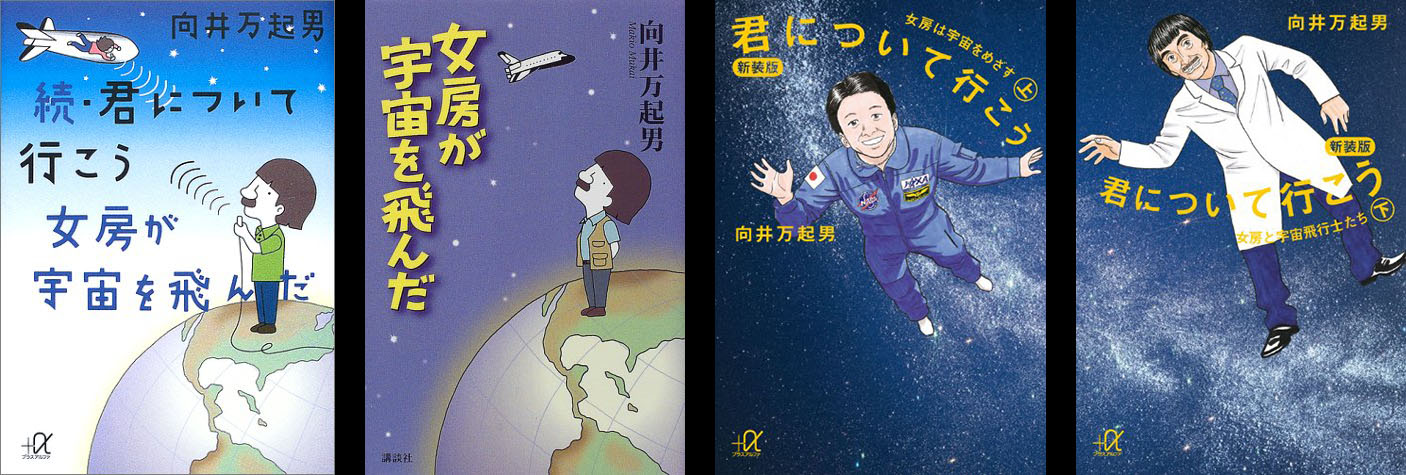

Chuya Koyama had two well-received sports manga under his belt in Morning magazine (published by Kodansha) when his editor suggested that he do a space story next. Koyama wasn’t well-versed in the subject, so he started reading books for research. The one that sparked him was I’ll Follow You ~ My Wife Went to Space, written by Dr. Makio Mukai, whose wife Chiaki Mukai was the first female Japanese astronaut in orbit.

Koyama described his thought process thusly in a 2015 interview: “In the book, one scene that left a strong impression on me was Makio Mukai watching his wife’s launch. It was refreshing to see how he was restless and anxious, but still paying attention to his surroundings. I thought it would be interesting to depict such a scene, one person going to space and another watching over them. I decided to replace it with two brothers. I somehow decided it was an older brother watching his younger brother launch.”

Different editions of Makio Mukai’s book, including a 2-volume set with covers by Chuya Koyama

“At first, I thought of Mutta as a potter (Laughs) or a school teacher. Somewhere around the outline of the first two chapters, I thought it would be more fun for him to become an astronaut. Since he’s an engineer, I thought he could be on the side of making rockets. But I thought it would be more interesting to become an astronaut with his brother.”

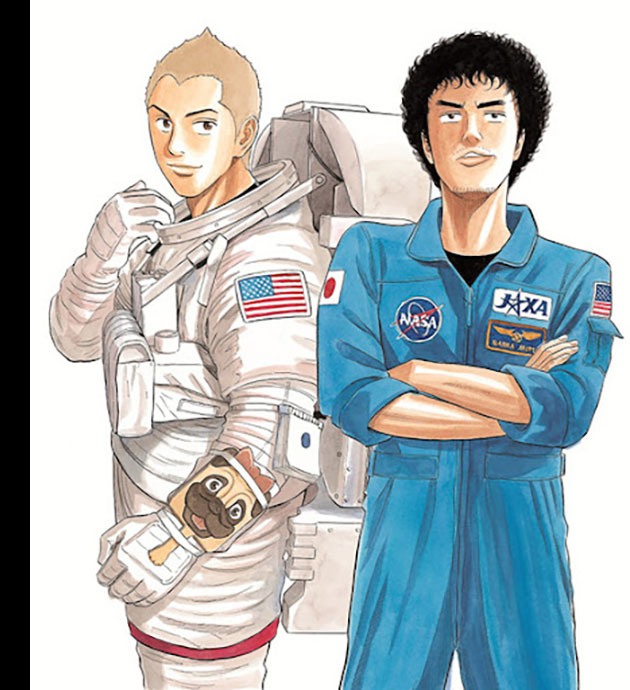

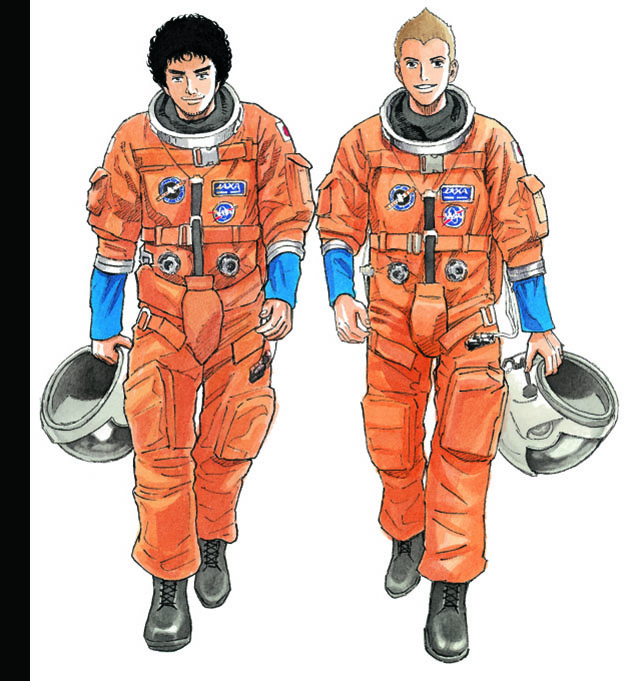

Koyama also decided to flip expectations; the older brother would trail behind the younger one and have to catch up. Mutta has a lot going against him at first, like his awkward demeanor, his weird hair, and his name itself. (in American terms, he would be a “Clyde.”) Hibito, by contrast, is outgoing, popular, and cool. Mutta is the one we follow as he works long and hard to close that gap. To begin with, he has to get into JAXA before he even has a hope of being noticed by NASA.

Space Brothers debuted in Morning magazine in December 2007 with the first collected volume appearing in March 2008. From there on, everything went right for Koyama. He and his staff did an incredible amount of homework to get the science right and learn what makes astronauts tick. But his true skill as an author lies in his ability to construct realistic characters with engaging personalities. They glide, they crash, they recover, they eat and sleep and laugh and cry and – like Koyama himself – wear their hearts on the outside.

What’s an example of something we see in every astronaut movie? I’ll answer it for you: a training montage. Movies have to tell a complete story in two hours, so they compress it wherever they can. Not Space Brothers. Successful manga stories are encouraged to go on as long as possible, and as a result we get to see every detail practically in real time. Remember, the series began in December 2007 and it’s still going as I write these words in December 2021, an amazing 14 years later. Only four years have passed in story time, but an incredible amount of activity has happened. Mutta has made it all the way to the moon, and that’s not even a spoiler because the story is about the journey rather than the destination.

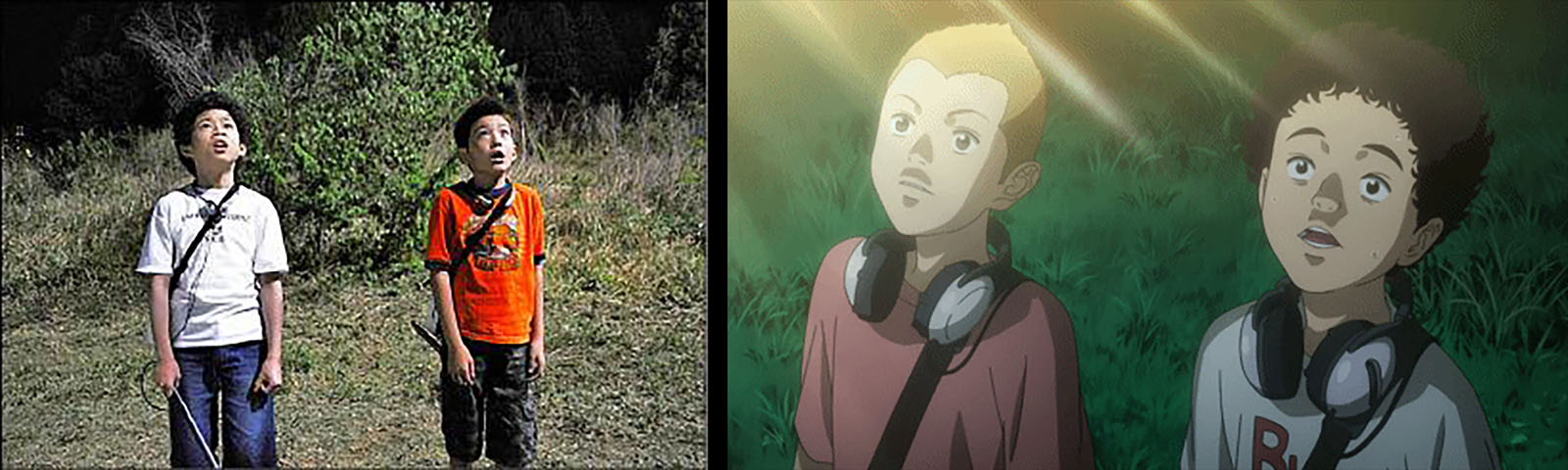

As we know, anime and film often go where manga has blazed the trail, and this is happily the case with Space Brothers. With manga sales leveling off a couple years in, Kodansha decided to give them a boost by launching an anime series and a live-action film simultaneously.

Take a moment to absorb that. An anime series and a full-blown movie created to boost a comic. Not the other way around. That speaks volumes about the difference between Japanese and American media. One of them is upside-down. As an author of comics, my choice of which should be obvious.

The series beat the movie by about a month, premiering on Yomiuri TV April 1, 2012 and catching fire right away. The movie hit theaters on May 5, which is the exact day Space Brothers first crossed my path.

I happened to land in Tokyo the day before, and had no idea Space Brothers even existed yet. My introduction was the movie posters and video banners that greeted me upon arrival. “An astronaut movie,” I thought. “They must have known I was coming.”

It was enjoyable, but it turned out not to be the best introduction to the story. I could follow the basics, but missed all the nuance. It didn’t help that, like all astronaut movies, it was compressed for time. Since it was shot on location at both JAXA and NASA, there were some English-speakers in the cast and the principal actors occasionally spoke broken English themselves. And Buzz Aldrin was in it, speaking English. But the director obviously didn’t, because they all felt like school play performances and sorta dragged down the experience. And then, of all things, there were obvious science mistakes in the lunar sequences. On the other hand, the special effects and music were phenomenal. It pulled in over a million viewers (very good for Japan) and won two major awards (including best picture) at the Puchon International Fantasy Film Festival.

So while I enjoyed it, the real Space Brothers experience still lay ahead of me. By a little over seven years.

The anime series ran for two solid years in Japan, ending in March 2014 with a whopping 99 episodes. Sentai Filmworks began releasing it to the west the following year. I knew I’d want to see it eventually, so I bought the Blu-rays one by one and finally cracked them open in the second half of 2019. This gave me everything I missed in the movie. All the character, all the nuance, and every moment that had been compressed out. It was the story I’d been waiting for, and I couldn’t get enough of it.

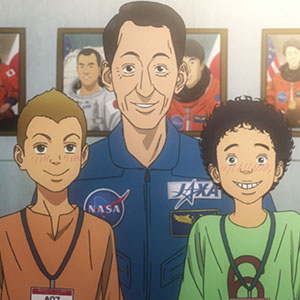

Like the movie, it was made with the enthusiastic cooperation of JAXA, leading to a “science moment” at the tail of each episode for the first year of broadcast. Koyama put real astronauts in the manga with slightly changed names, but their actual names were restored when they were drawn into the anime, and one of them, Akihiko Hoshide, became the first voice actor in space when his lines were recorded from the ISS in Earth orbit (details here).

To compare story content, the movie covered roughly the first half of the anime series with a lot of jumps and reorganizing to make events happen simultaneously. While watching the second half of the series, I went back to Japan and quickly found a copy of the movie on DVD. Seeing it again with proper context brought it back to life the way it was meant to be seen. I was able to overlook the flaws and gain a new appreciation for it. Especially the lead actor Shun Oguri, who played Mutta with absolute perfection. Incidentally, the movie jumped forward to an ending all its own. Whether Koyama adopts it as the “real” one remains to be seen.

But whereas the movie was abridged, the series followed the manga practically line for line with new material added, all endorsed (and occasionally contributed) by Chuya Koyama himself. Production was by A1 Pictures, who did phenomenal work from start to finish. And again, the music was outstanding. But all good things must come to an end, and for whatever reason 99 episodes was the limit. I would have happily sat through another 99.

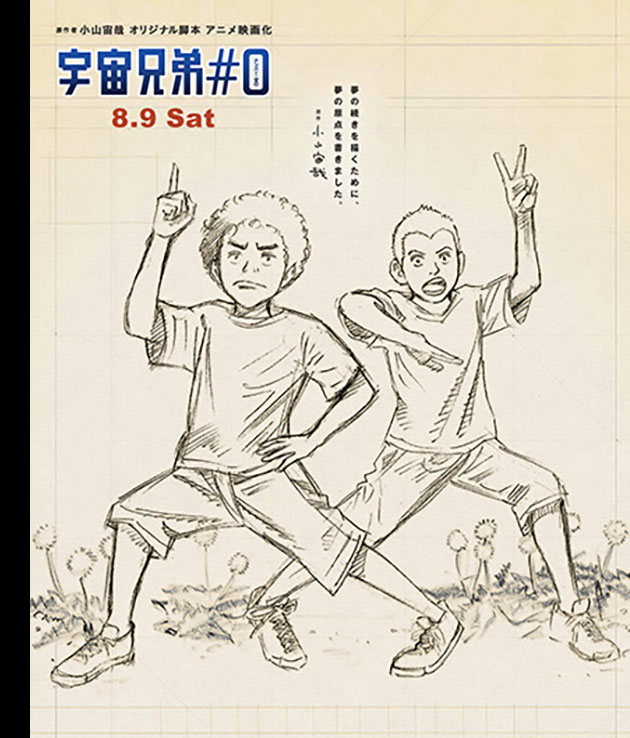

But here’s the thing; the manga kept right on going. Koyama was up to Volume 17 when the anime and movie arrived, and the anime only got to the end of Volume 18. When it went off the air, the manga was on Volume 23 and it hasn’t stopped since then. As of December 2021, it’s all the way up to Volume 40. In other words, the amount story adapted into anime has more than doubled since the series finished. The anime hasn’t come back (and probably won’t, given how much time has passed) but a prequel film titled Space Brothers #0 (written by Koyama) premiered in August 2014 and has since been added to the Sentai Filmworks catalog.

Other spinoff media has come and gone as well. A weekly radio show titled We Are Space Brothers accompanied the TV series for its entire run, then got extended through September 2014 as a tie-in to the prequel movie. A semi-annual art exhibition has appeared since 2015. Numerous books have been published, some about the series and others inspired by it. This includes writing on leadership, teamwork, space history, self-help, and even cookbooks.

A set of animated shorts titled Apo’s Dream predated the TV series by a month. Two original planetarium shows added more to the anime; A Flash of Light in summer 2012 (expanding on a TV episode) and Space Dreamers in summer 2017 (an original story written by Koyama). All three of these programs have been released on DVD, but like the 2012 movie, they remain unimported.

In the wake of all these “extras,” the real story continues to be the manga, which has won numerous awards and brought many further honors to its author. This includes having an asteroid named after him (13163 Koyamachuya) and getting his artwork on the side of a rocket that launched a weather satellite in November 2016. Pretty good for a guy who didn’t know much about all this when he started.

If you’re a space enthusiast, Space Brothers was absolutely made for you. If you’re not, Space Brothers was still made for you. It’s an extended astronaut movie where all the montages play out in full. It’s set in a world of infectious passion and esprit de corps, where characters overcome pettiness, arrogance, and selfishness to become better people. Opponents gradually become allies. Dreams are inherited from those who came before. Chuya Koyama is a master at depicting humanity with all its flaws and strengths.

He also has a particular advantage as a Japanese writer. JAXA is by definition an underdog in the global space effort with NASA and Roscosmos as the big kids. If this story were invented in America or Russia, it would inevitably be framed by its own nationalistic roots. But Koyama doesn’t play favorites; JAXA partners with both sides, and a substantial part of the story takes place in Russia with just as much flavor and insight as the US-based segments. It’s a sobering reminder of the limits placed on all the NASA-centric movies we grew up on.

So…what is it about Space Brothers that could possibly make me angry?

At the risk of sounding jingoistic (not my intent), it’s the kind of story that should have come from right here in the US. It’s perfectly suited to us, big and bold and optimistic. It should have been easy for something like this to find a waiting audience in the country that invented both the comic book and the public-facing space program. It should have been a no-brainer for an American publisher, American retailers, and an American readership to snap it right up.

I’m angry that we don’t have the conditions for that to happen here. I’m angry at myself for not coming up with something like it. (If you’ve seen my webcomics Grease Monkey and Pitsberg, you know it’s right in my wheelhouse.)

I’m also angry that we’ve allowed our national pessimism to erode the spirit that put us into space to begin with. I’m angry that we as a country care so little about this national treasure that we’ve chosen NOT to have a world like the one depicted in Space Brothers, with a thriving lunar program, an engaged society, and room for incredible strides to be taken. We don’t have any of that. We can only find them in a story. And that story had to come from another country that hasn’t lost its sense of wonder yet.

All it takes for me to get past that anger is to dive into the latest manga chapter or put on some soundtrack music, and I’m instantly transported there. I just hope I live long enough to reach a time when those things are not necessary.

Chuya Koyama has been asked more than once how long he intends for the story to last, and the answer constantly changes. He has an image in mind for the ending, but no specific plan for how to get there. New story arcs keep blossoming and pushing that ending farther down the road. Which is just fine by me. I’m on board for the whole ride.

It was pretty gutsy of him to set this story within his own lifetime, since it wouldn’t be long before reality turned in a different direction. Like all near-future space program stories, it has already fallen victim to its own optimism. He keeps pace with research and adopts the newest developments when he can, but too many things have stalled out to set the conditions for his version of 2025. At this point, Space Brothers exists in another world. Fortunately, we can visit it any time we want.

Here’s how:

Watch all 99 episodes online for free at Crunchyroll here (Upgrade your account to axe the commercial breaks). It’s also streaming on Hidive. Or you can buy it on Blu-ray and have it forever.

Then sign up at Comixology here for the manga. Start with Volume 1, or watch the anime like I did and jump in seamlessly at Volume 19. Then you can read all the way up to the current chapter and continue forward in real time.

Meanwhile, here’s a lot more to keep you hooked…

Related Links

Manga page at Anime News Network

Anime TV series page at Anime News Network

Space Brothers #0 page at Anime News Network

Live-action movie page at Anime News Network

2016 interview with Chuya Koyama (more below)

Order Blu-rays from Right Stuf

Movie promo with Apollo 11 tribute

Apo’s Dream and A Flash of Light (untranslated)

Space Brothers Art Exhibition video (English)

Photos of art exhibition in Kyoto, September 2014

Find many more links in the sections below.

Interviews with creator Chuya Koyama

INTERVIEW 1

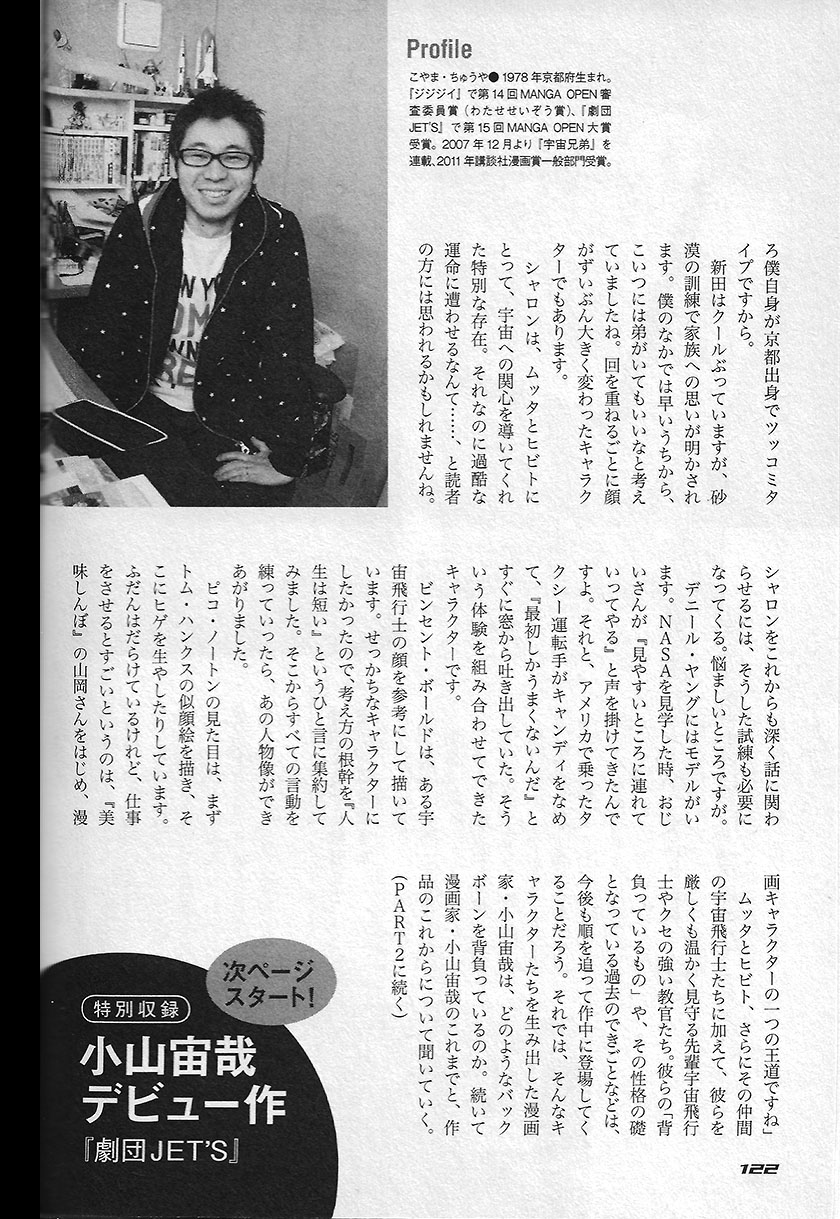

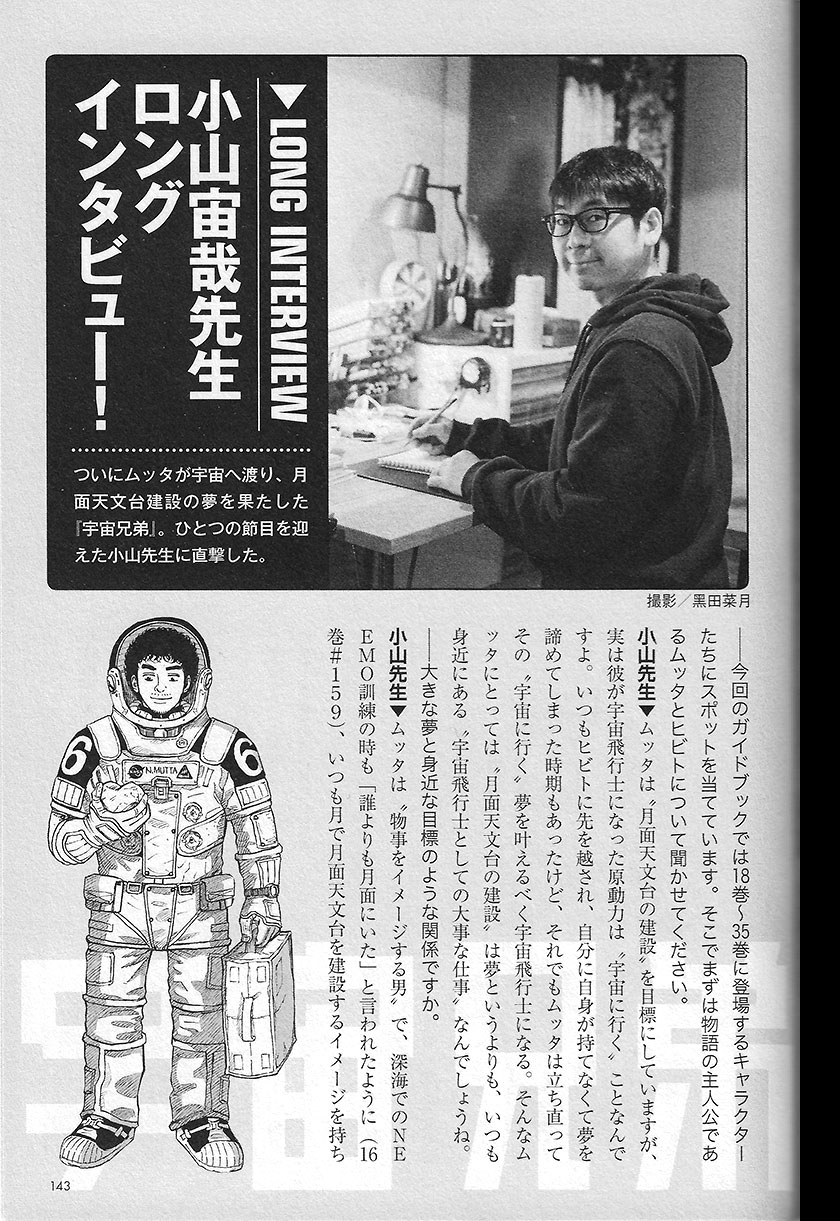

Published in Space Brothers Comic Guide 1, June 2012

Space Brothers has been a major factor in the “space boom” of the past few years. We would like to talk about how Mutta, Hibito, and the other main characters were born, the process of creating each piece, and future developments of the work. We had a direct interview with the author, Chuya Koyama!

Creating the current outline is the biggest challenge

The serialization of Space Brothers, which began at the end of 2007, has already entered its fifth year. When we asked Mr. Koyama about the biggest hardship he has faced so far, the thing that left the greatest impression on him, the answer came back immediately.

“I have a tendency to forget past hardships easily. I’ve been having a hard time with outlines lately. It takes me almost four days to write each chapter. I’d really like to do it faster, but it’s not easy.”

He often thinks about his ideas in a restaurant or coffee shop. He starts by writing notes on the events and scenes he wants to portray.

“Then I write outlines for each scene as if creating a script. It’s like making a movie in my head. I repeat the process over and over again, making choices, refining, and solidifying the story. It takes a long time because I have to do this work little by little and with great precision.”

Once the story has been written, he begins to work on the rough layout. From this stage on, the work is done in collaboration with five assistants. Of course it takes time, but they don’t stay up all night.

“If I’m sleepy, I can’t draw, and it ends up taking even more time. So I go to bed around 3 a.m. and wake up around 8 a.m. on average. The assistants go home at 10 p.m. and come back in the morning or afternoon. However, on the last day of a chapter, we usually work together until morning to finish it.”

While one chapter is completed in this way, preparations for the next one must be made at the same time. While he finishes a chapter, he has a meeting with the editor in charge to discuss the outline for the next one.

In the early days of the series, they had a lot of things to discuss and many clashing opinions. Now, as the author, he has a good grasp of the world of the work (according to the editor) and the editor only has to tell him what’s interesting about the outline and the chapter in progress.

“I’ve come to be very strict about checking my own work. I guess it’s paying off.”

Mutta’s face came from a band’s guitarist

There are a lot of characters in Space Brothers, and each of them lives in their own world. How were these fascinating characters created? What kind of thoughts and roles were entrusted to them? Let’s start with Mutta. In terms of visuals, there is someone who was clearly the model.

“He’s based on Albert Hammond, Jr., the guitarist for The Strokes. When I was thinking about the character of Mutta, I happened to have a picture of him at home. I drew him that way and got a good feeling from it.”

Koyama decided from the beginning that the only thing we needed to know about Mutta was that he paid attention to details.

“Mutta is a character that came to me very naturally, so it’s hard to explain. I got a hint for the initial concept from [author] Makio Mukai. When I read his book, I’ll Follow You, he remembered the people he met very well. I thought it was interesting that he paid attention to every detail. Starting from there, while I drew Mutta I felt like he would keep his room clean and he was surprisingly good at cooking.”

“Another basic part of his character is that no matter how cool he is, he can never be cool enough. This is an important point. Even if he says cool lines, it won’t feel right. That’s what I wanted from the beginning. I was conscious of this when I named him Mutta. No matter how cool he acts, his name itself can never be the name of a cool guy. And it has an interesting sound. On the other hand, for Hibito, I wanted him to have a cool name. In my mind, a name with a ‘to’ at the end is very cool.”

Mutta is also capable of doing many things at the same time in his daily life. This is a concept reflects an awareness that he’s a person who aims for space.

“From reading materials and conducting interviews, I realized that it is important for an astronaut to perform multi-tasking. You have to do a variety of tasks while wearing a space suit and listen to instructions from ground control, so it makes sense. If you have to have such qualities to become an astronaut, then Mutta has them, even if he isn’t aware of it.

Basically, Mutta doesn’t think much of himself, does he? He’s a step behind Hibito, so he has feelings of inferiority. However, he’s capable of multi-tasking and has a great deal of concentration, so his abilities are quite high. Although he doesn’t realize it, he’s actually a genius. He’s like a genius who can’t be confident.”

How were Hibito and his parents created?

So, how was Hibito’s character formed?

“I don’t have a model for Hibito, either formally or internally. I was thinking about what kind of character I wanted to make, and I was doodling around. It came about naturally. I first drew him as a child, and then I thought I’d give him a strange hairstyle. That’s how I came up with the shaped hair. The design is similar to the character I used to draw in my manga before Space Brothers.”

“As for who he is inside, I think it was mostly decided as I drew. My first thought was to make him the opposite of Mutta in many ways. He doesn’t care about details, and he’s a very rough and random guy. But when it comes to being an astronaut, he’s focused and committed to it. He may be a difficult character to depict, because his weaknesses aren’t so visible.”

The relationship between the two brothers is naturally the axis of the story. Although their childhood and adulthood are depicted, there are no scenes showing what kind of relationship they had in their junior and senior high school years. Is there an idea for that?

“I don’t know, I don’t really have a specific “how it was” in mind. However, I think there was some distance between them. Hibito was on a straight path to his dream while Mutta lagged behind and gradually gave up on his. He thinks Hibito is ‘awesome’ but doesn’t talk to him much.”

The Nanba family’s parents don’t appear often, but they always leave a strong impression.

“Their mother is a natural and absent-minded person. Hibito lives in America and there’s an episode in which his mother delivers kimchi that is just about to expire. This is based on a true story of my wife’s mother, who sent us kimchi that was just about to expire. Since their mother is such a character, I imagined their father as someone who would be able to get along with her, someone quiet and composed who would not get upset with her eccentric behavior. In my opinion, they’re the ideal couple.”

Serika’s appetite for food is like Chiaki Mukai’s

The story features friends who aim for space together. How were they born? First, let’s talk about Serika Ito.

“I didn’t have a specific model, but I found her hairstyle by flipping through women’s magazines and choosing one that looked refreshing. The fact that she eats a lot is a reference in I’ll Follow You where Chiaki Mukai said she eats a lot. I thought it would be nice to have a strong and healthy woman. When Serika gets older, I think she will be like Mutta’s mother.”

“She lost her father when she was very young, and that had a big impact on her personality development. Her father’s influence on her life is quite significant. She wants to study medicine in space because she witnessed her father’s illness. I think there is still a lot of meaning to the character of Serika in this work. I think she will have an important role to play in the future.”

What about Mutta’s best friend, Kenji Makabe?

“I drew him with a retro hairstyle that reminded me of a guy in my junior high school soccer club. I thought it would be fun to see someone with an old-fashioned Yankee hairstyle in 2025, and I wanted him to be playful, but I thought it would be better to have a gap and make him serious on the inside. The kind who would give a quick, firm handshake because he’s so serious. I think it’s attractive to have your own way of doing things.”

“I also wanted to portray an astronaut who has a wife and daughter. But it’s hard to find drawing reference for a house with children. I have a daughter, so I drew Kenji’s house based on the house I used to live in. I also used my daughter’s words and actions in the dialogue between Kenji and his daughter. When he goes out, she says ‘kapeh’ to mean ‘ganbare’ (do your best), and ‘Do it’ instead of ‘Don’t overdo it.’ I just used what my daughter said when she was about three years old.”

Various models from friends to instructors

The other strivers also have their own stories.

“Furuya, a.k.a. Yatsu-san: I had a classmate in junior high school who was just like him. He’s a yankee, but he’s small and not too scary, and he is easy to draw as a straight-man type from Kansai. After all, I myself am from Kyoto, and I’m a straight-man type.”

“Nitta is a cool guy, but his feelings for his family are revealed during desert training. I thought early on that he should have a younger brother. He’s also a character whose face has changed a lot over the years.”

“Sharon is a very special person to Mutta and Hibito, since she was always the one who honored their interest in space. However, readers may think she’s had a harsh fate. In order to keep Sharon deeply involved in the story, such an ordeal is necessary. It’s troubling.”

“Daniel Young has a model. When I toured NASA, an older guy told me, ‘I’ll take you to a place where you can see it better.’ And a taxi driver in America licked his candy and immediately threw it out the window, saying, ‘It only works the first time.’ This character is a combination of those experiences.”

“Vincent Bold was drawn with the face of an astronaut as reference. I wanted to make him an impatient character, so I summarized the basis of his thinking as, ‘Life is short.’ From there, I worked out all his words and actions, and that’s how I came up with him.”

“For the look of Pico Norton, I started with a caricature of Tom Hanks, then added a beard. I’ve always thought of him as a guy who is usually full of himself, but when he’s working, he’s amazing. It’s a classic example of a manga character, such as Yamaoka-san from Oishinbo.”

In addition to Mutta, Hibito, and their fellow astronauts, there are senior astronauts and instructors with strong personalities who watch over them warmly but strictly. What they are “carrying” on their backs, and what happened in the past that forms the basis of their personalities, will be revealed in future chapters. So, what is the backbone of the manga artist Chuya Koyama, who created these characters? Next, we talked about his past and future.

Works are born with music

It has been five years since the start of the series. It is still unclear what fate will befall Mutta and Hibito. It was under such circumstances that Koyama was approached to make an anime and a movie. As a result, the work became more widely known to the public and a new readership was developed. However, as an author, he had mixed feelings about his ongoing work being developed in multiple ways.

“I was definitely happy about it, but I thought the timing was a little too early. Mutta hasn’t been to the moon yet, and I still haven’t decided how the story will go. Even though it was in a different format, I still felt uneasy about having someone other than myself create the story.”

Even so, he was able to sort out these feelings by discussing the film with the director and his staff many times, and by getting involved in the scriptwriting for the anime.

“I could tell that the director of the film, Yoshitaka Mori, was working on the project with great enthusiasm, so I felt like I could trust him. Of course, there were many things that I pointed out. This person wouldn’t say such a line. Mutta wouldn’t do this kind of thing. If they agreed with me, I asked them to change it, and if they thought it should be this way from a cinematic point of view, I left it as it is. Anyway, it was great to be able to work together to create something new.”

And there was one more thing that made him happy: “It’s really nice to see the pictures move with music you love, isn’t it?”

Yes, in both the movie and the anime, the choice of the score and theme music was a strong reflection of Mr. Koyama’s tastes.

“Whenever I draw, I always listen to my favorite music. So I gave the film producer a CD that I listen to when I draw. I thought it might help him get an image. Then they actually used a lot of it in the film. Coldplay, who performed the end title song, was one of the bands on the CD. As for the anime, the first opening theme song was written by Unicorn, a band I love and listen to all the time. It’s a dream come true.”

When we asked him to list some of the songs he usually listens to, he cited strong rock sounds, both Western and Japanese. On the Japan side, he often plays Unicorn, The Highlows, The Cro-Magnons, The Beat Crusaders, and Eastern Youth. As for western music, he likes Coldplay, Sigur Ros, Primal Scream, Rancid, The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Arcade Fire, and more. These artists’ songs were included in the CD that he gave to the film producer.

The first step toward success

What was the path of the manga artist who came to prominence with Space Brothers? Was he a boy genius? Or did he yearn for space like Mutta and Hibito?

“Looking back on my elementary school days, I don’t think I liked studying very much. All I remember is playing around outside with my friends in the neighborhood. If you were to ask me what my hobby was, I think the best answer would be soccer. However, for a while it was popular to copy manga with my friends. One of the most famous manga of that time was Dragonball. I used to watch the anime for Fist of the North Star. I liked the classic manga. At that time, I sometimes dreamed of being a soccer player, and at other times, a manga artist. When I was in the fifth grade, I saw a documentary feature on Osamu Tezuka in my school class. It gave me a growing desire to draw manga.”

“I was good at drawing, so I went to an art high school. My first choice was western painting, and my second choice was ceramics. I guess I made a mistake in my drawing test, so I decided to go into ceramics. I made a ceramic piece in which all the Chess pieces were replaced with ancient monuments.”

“After graduating from high school, I went to a design school in Osaka. After that, I went to work at a design company near the school. I worked there for about five years, during which time I drew my own manga and showed them to publishers.”

In fact, he established a connection with a publisher [Kodansha] from his first visit. He was encouraged to submit his work for the Morning manga open contest and left his submission there. Later, his work Jijiji~GGG won the 14th manga open judging committee award (the Seizo Watase Seizo Award). Did he have confidence in his work from the start?

“No, it wasn’t that I wanted to make a debut with this work. I just wanted to have a pro look at it and see if I had the talent to draw it. I was 24 years old when I went on an overnight trip from Kyoto to Tokyo for to bring in my work. Did I have confidence? I’ve forgotten how I felt and what I was thinking. But I knew that I wouldn’t stop doing comics even if I was told I couldn’t do it there. No matter what anyone says, if it’s something I want to keep doing, then I’ll keep doing it. That’s a definite.”

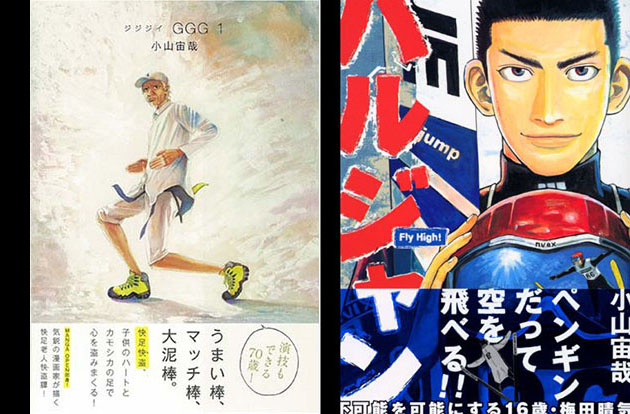

I wanted to draw real space

After Koyama’s debut, he established his reputation with Harujan and Jijiji~GGG, both of which were sports manga (shown below right). Then, at the end of 2007, he started on Space Brothers at the age of 29.

“I’m often asked why I chose ‘space’ and ‘brothers.’ It’s not that I was always a space fan. The truth is that my editor said, “How about space?” I wanted to work in a genre that would attract fans. I thought there must be readers for the theme of space, and that’s how the idea came about. There were also other candidates, such as ceramics, which I used to do in high school, and war stories.”

“Thinking about space, I decided to do some research and read Makio Mukai’s I’ll Follow You, which was very decisive. In it, he wrote a lot about the process of becoming an astronaut and the daily life of an astronaut. It’s interesting that not everyone knows the realities of space, which is all around us. I thought this was a good idea.”

The idea of making it a sibling story also came out of the conversation with the editor.

“Mukai-san’s book was about a couple [his wife is an astronaut], so I thought a family story would be good. I don’t have any siblings, but I imagined what they would be like. There’s no rule that a brother should be a certain way, so any kind of brother should be possible. There are many examples of siblings in which the younger brother is more active. The manga Touch is a perfect example. The Wakagi brothers in sumo and Kazu Miura and Yasutoshi Miura in soccer are also patterns where the younger brother moves ahead. When I see them, I feel like cheering for the older brother. So I decided to focus on Mutta, who is lagging behind.”

How will the ongoing story of Space Brothers unfold in the future? What kind of climax could it have?

“For now, I want everyone to go to space as soon as possible. Mutta, Kenji, and Serika. I’m just going to keep moving toward that. Each of them is carrying something on their shoulders. The path to space is different for each of them. I have to worry about which one to show first.”

“I haven’t really thought about where the goal is yet. However, in the end, it’s a story about the brothers. I have a scene in mind that I want to draw at the end. In reality, though, I’m more occupied with the next outline. However, it is the accumulation of these thoughts that builds up a story, isn’t it?”

He was a soccer boy who was good at drawing, but after watching Osamu Tezuka’s documentary in class, he thought, “I want to be a manga artist.”

It was about 25 years ago that he realized he wanted to do this.

From there, he went to an art high school and a design school, worked at a design office, then took his first steps as a manga artist.

There were many possible paths he could have taken along the way, but they all led him to his childhood dream of becoming a manga artist. At the age of 30, he arrived with a big hit. This naturally overlaps with Mutta, who regained his dream of becoming an astronaut through many twists and turns after turning 30.

“I’m more like Mutta,” Koyama says.

Let’s keep an eye on how he depicts his alter ego.

INTERVIEW 2

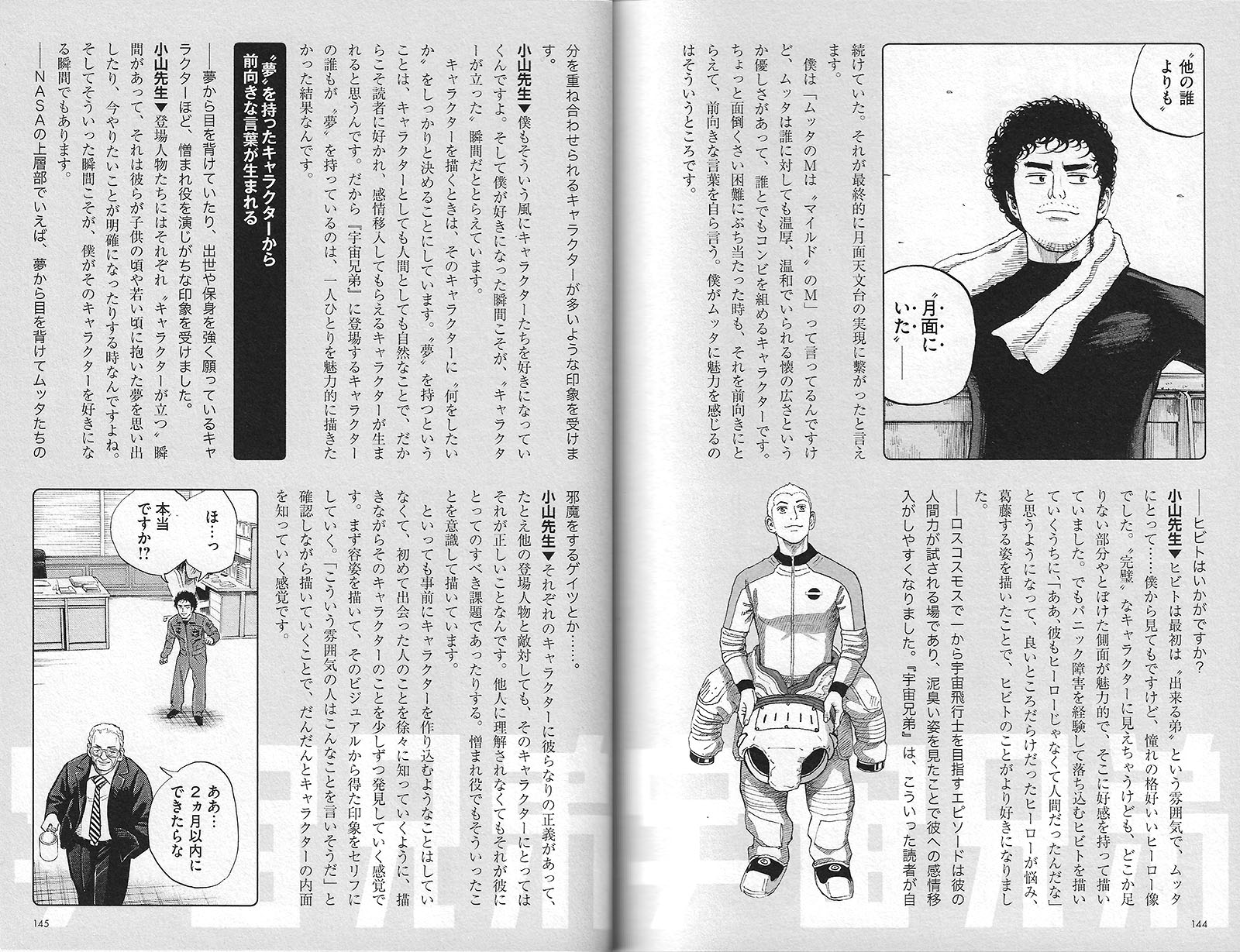

Published in Space Brothers Comic Guide 2, February 2021

Finally, Mutta went to space and fulfilled his dream of building a lunar observatory. We interviewed Mr. Koyama, who reached a milestone.

Interviewer: In this guidebook, we focus on the characters who appear in Volumes 18 to 35. Please tell us about Mutta and Hibito, the main characters of the story.

Koyama: Mutta’s goal was to “build a lunar observatory,” but actually, his motivation for becoming an astronaut was to “go to space.” Hibito always beat him to it. There was a time when he gave up on his dream because he couldn’t do it himself. Even so, Mutta recovered and became an astronaut to make his dream come true. For Mutta, “building a lunar observatory” is not a merely dream, but rather an “important job as an astronaut” that is always close to him.

Interviewer: Is there a relationship between a big dream and a familiar goal?

Koyama: Mutta is a “man who imagines things.” During the NEEMO training in the deep sea, he was said to have been “on the moon more than anyone else” (vol.16, chapter 159). He always had the image of building a lunar observatory on the moon. This is what ultimately led to the realization of the lunar observatory.

I say the M in Mutta stands for “mild.” Mutta has a warmth and gentleness about him, and he can work with anyone. Even when he encounters difficulties, he takes them in stride and says positive things about them. That’s what I like about Mutta.

Interviewer: How about Hibito?

Koyama: Hibito started out as the “can-do” brother, and as for Mutta…even from my point of view, he had the image of a cool hero. He seemed “perfect.” The missing parts and blurry sides of him were attractive, and I had a good feeling when I depicted them. But as he became depressed because of his panic disorder, I began to think, “Oh, he isn’t a hero either, he’s a human being.” I became more fond of Hibito through the story as I depicted him as a hero who was still worried and struggling despite his good points.

Interviewer: The part where he tries to become an astronaut again from scratch at Roscosmos is where his human power is tested. Seeing him get down and dirty made it easier to empathize with him. I get the impression that there are many characters in Space Brothers that readers can relate to.

Koyama: When I create a character, I try to decide what I want to do with them. Having a “dream” is a natural part of being both a character and a human being. I think that’s why I can create characters that readers like and can relate to. That’s why every character in Space Brothers has a “dream,” because I wanted to portray each one of them in an attractive way.

Positive words are born from characters who have “dreams”

Interviewer: The more a character turns away from their dreams, or strongly desires to get ahead or protect themselves, the more likely they are to play the role of an antagonist.

Koyama: Each of the characters has their “standing up” moment. It happens when they remember the dreams they had when they were younger, or when they have a clear idea of what they want to do now. And those are the moments when I fall in love with them.

Interviewer: In the case of NASA’s upper management, It is Gates who turns his back on his dreams and gets in the way of Mutta and the others.

Koyama: Each character has their own justice, and even if they antagonize other characters, it’s the right thing to do for that character. it’s a challenge for them when others don’t understand them. I have that in mind even when I depict an antagonist.

However, I don’t fully create a character in advance. It’s like getting to know someone you’ve never met before, and gradually discovering their character as you portray them. I draw them first, and then create lines for them based on the impression of the visual. It’s a feeling of gradually getting to know the inner workings of a character.

Interviewer: That’s where all the indispensable quotations in Space Brothers come from, isn’t it?

Koyama: I’m attracted to the positive lines of a character. Whenever a character speaks to someone, I don’t just take the stock of words I write down and put together to suit the character, I also try to think of words that they might say. Sometimes words and phrases that I hadn’t thought of come out of nowhere. Pico’s line about why he wears a necktie (Vol. 12, chapter 114) is one of those. It came naturally to me when I was drawing that scene.

Interviewer: I heard that you are particular about the sense of rhythm.

Koyama: I think it’s important to make the words easy to read in manga. I always try to keep the sense of rhythm and the number of words as compact as possible to make it easier for readers to understand. So I arrange what I want to convey in each character’s phrasing and brush it up from there.

There’s Sharon’s line, “We live to give someone else the courage to live” (Vol. 24, chapter 232). It’s also fine to say, “I give courage to someone while they give courage to me.” But by putting “receiving courage” at the end, it’s easier to convey the emotion in the line, and you can feel it grabbing your heart. It’s that kind of attention to detail.

When Mutta’s father says his name in disguise (Vol. 37, chapter 343), he doesn’t just say it quickly, he says, “Takakura…Leon. (Laughs) The pause brings out the character of the father. I calculate such things while writing lines.

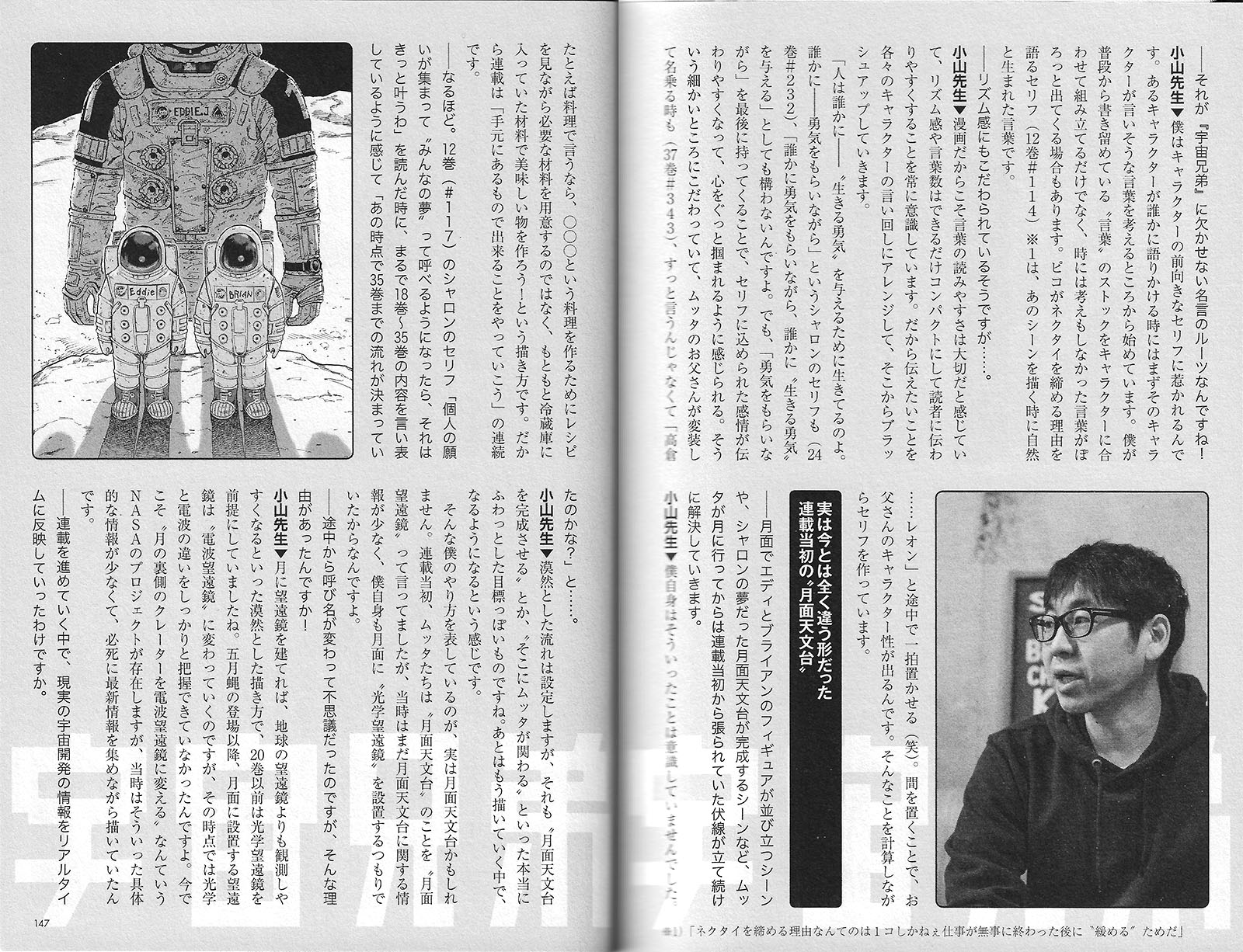

The “Lunar Observatory” at the beginning of the series was actually a completely different shape than it is now

Interviewer: There’s the scene where Eddie and Brian’s figures are standing side by side on the moon, and Sharon’s dream of building a lunar observatory is completed. After Mutta’s trip to the moon, the foreshadowing that had been going on since the beginning of the series is resolved, one event after another.

Koyama: I wasn’t aware of those things myself. For example, in the case of cooking, instead of looking at the recipe and preparing the necessary ingredients in order to make something scientifically, you can use the ingredients that are already in your refrigerator. This is the way I draw. That’s why the series is a procession of “let’s do what we can with what we have at hand.”

Interviewer: I see. In Vol. 12 (chapter 117) Sharon says, “When the wishes of individuals come together and can be called ‘everyone’s dream,’ it will come true.” When I read that, I felt as if she was describing the contents of volumes 18-35. I wondered, “Was the flow up to volume 35 already decided at that point?”

Koyama: I do have a vague idea of how it’s going to play out, but it’s more like, “We’ll complete the lunar observatory,” or “Mutta will be involved in that.” After that, I just let it happen as I draw.

In fact, the lunar observatory is probably the best example of my approach. In the beginning of the series, Mutta and his team called the lunar observatory a “lunar telescope.” At that time, there was not much information about lunar observatories, and I was planning to set up an optical telescope on surface of the Moon.

Interviewer: I was wondering why you changed the name in the middle like that.

Koyama: It’s a vague way of saying that if we build a telescope on the moon, it will be easier to use than a telescope on earth. Before Volume 20, I assumed it would be an optical telescope. But at one point, telescopes on the moon were changed to radio telescopes. I didn’t have a firm grasp of the difference between optical and radio telescopes, although there is now a NASA project to convert a lunar crater to a radio telescope. At that time, there was not much concrete information. I was desperately gathering the latest information as I drew.

Interviewer: As you were working on the series, did you reflect the information about real space development in realtime?

Koyama: Yes, I did. The lunar observatory completed in Volume 35 is in a form that could actually exist. It was supervised by Dr. Masaaki Hiramatsu of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. Mutta had a diagram that said “flat/shiny,” meaning an optical telescope, but that didn’t end up in the story. Instead, there are two telescopes in the lunar observatory: a military wave telescope and an optical telescope.

This kind of thing happens a lot in Space Brothers I try to anticipate what JAXA, NASA, and astronomers will make in the future. That’s why they often turn out to be different from what was originally expected. (Laughs)

Interviewer: It sounds like you’re having a lot of fun drawing things that haven’t been realized yet!

Koyama: Speaking of which, here’s something happened to me a few years ago. There was a news report that a vertical shaft had actually been found on the moon. There was an uproar among the readers who saw it. “It’s the vertical shaft they found, isn’t it?” In the minds of the readers, reality and the “Carlom Cave” event in Space Brothers became one and the same. (Laughs)

Interviewer: It’s true that when I read Space Brothers, I sometimes lose track of where things are in reality. (Laughs) On the other hand, is there anything in Space Brothers that has been overtaken by real space development?

Koyama: In the new spacecraft Crew Dragon (launched on November 16, 2020) with astronaut Soichi Noguchi on board, the booster detaches from the rocket and lands on a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean on autopilot. I wish they had told me about that a little earlier! (Laughs) The rocket in Space Brothers is a detachable and disposable type, so I would have loved to draw it this way if the information had come in a little earlier. If the series goes on for a long time, there will be things like this, small and large. After all, Hibito is using a Feature Phone in volume 1, chapter 1. (Laughs)

Interviewer: (Laughs) Isn’t it a kind of joy to be overtaken by such reality?

Koyama: It is a joy, and I wanted to depict it as early as possible in the story. The system that the Jokers installed on the moon base to bring sunlight into the base (Vol. 28, chapter 260) is an example of an element that is ahead of reality. In the story, based on the latest information available at the time, they built a chimney with an electric mirror at the base. The reflected sunlight is diffused and illuminated by a prism inside the base.

But in recent research, the mechanism has the prism installed at the top. With the prism, sunlight can be captured from any direction in 360 degrees. There is no need to use a motorized mirror to track the direction of the sun. Maintenance would also easier with just a prism, wouldn’t it? But I wanted to draw it with that mechanism!

The conflict of depicting ALS, and thoughts about the end of the story

Interviewer: Please tell us about Serika’s ALS mission. Why did you decide to depict the disease ALS?

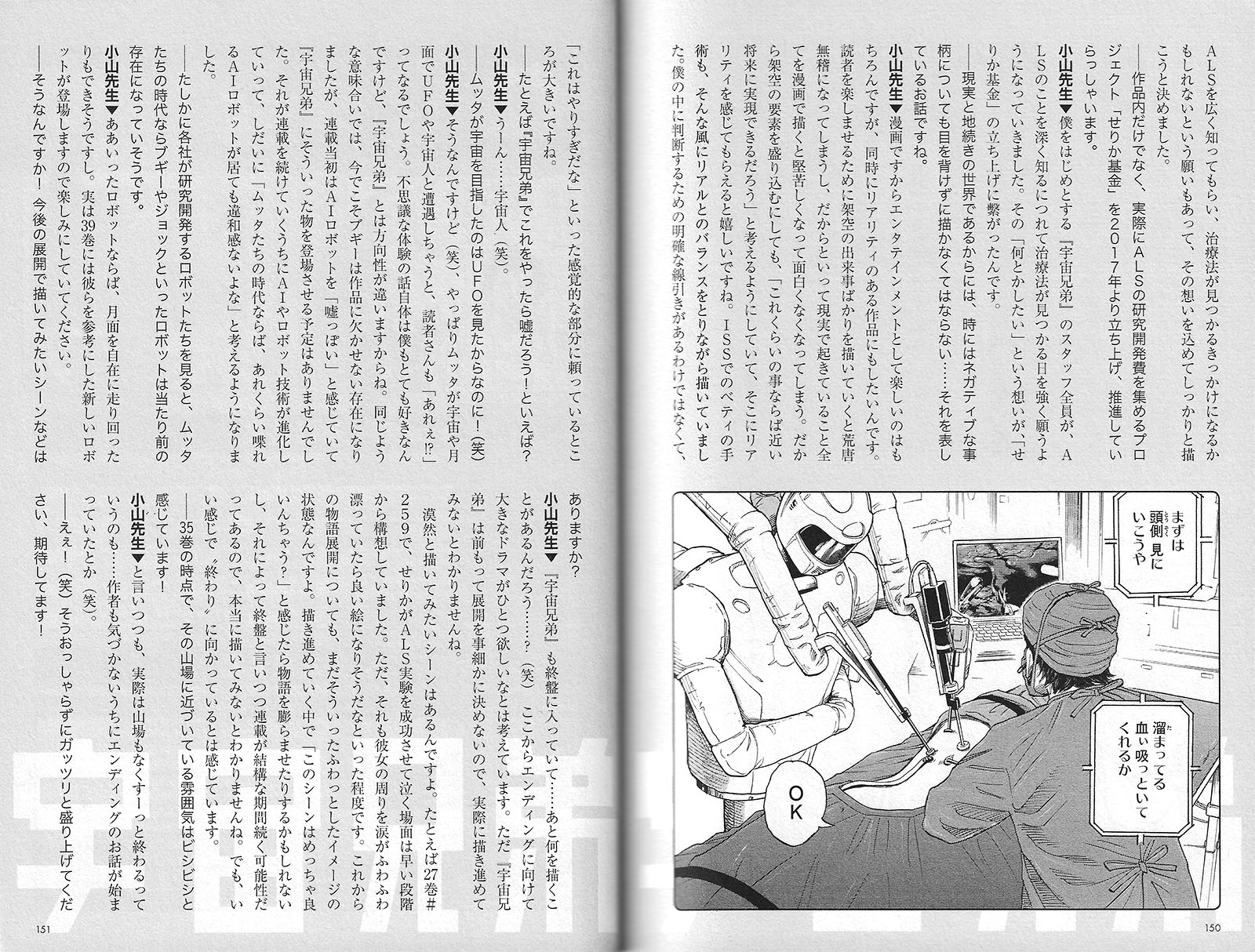

Koyama: It all began when I started thinking about what kind of research can be done on the Japanese Experiment Module Kibo at the ISS. Initially, I was thinking of researching a fictional disease, but the doctor who consults on my work told me about ALS. However, even if it would bring reality to the story, I was still very conflicted about depicting it. But I also hoped that my depiction would make ALS more widely known and help find a cure. So, I decided to portray it with that in mind.

Interviewer: And in 2017, you launched the “Serika Fund” project to raise funds for ALS research and development.

Koyama: As all of us on the Space Brothers staff learned more about ALS, we began to hope for the day when a cure would be found. This desire to do something led to the launch of the “Serika Fund.”

Interviewer: Since the Space Brothers world is connected to reality, sometimes it is necessary to depict negative things. That’s what this story represents.

Koyama: It’s a manga, so of course it should be fun as entertainment. But I also want it to be realistic. If I depicted only fictional events to entertain readers, the story would become ridiculous. On the other hand, if I depicted everything that happens in reality in my manga, it would become too rigid and uninteresting. That’s why, when I include fictional elements, I try to think, “This is the kind of thing that could come true in the near future.” I’m happy if people can feel the reality of it. That’s how I drew Betty’s surgery on the ISS, balancing the real with the imagined. I don’t really have a clear line of judgment, so I rely heavily on my sense of “this is overkill.”

Interviewer: What would be an example of a lie if you put it in Space Brothers?

Koyama: Uh…aliens. (Laughs)

Interviewer: Mutta aimed for space because he saw a UFO! (Laughs)

Koyama: Yeah, but… (Laughs) if Mutta encounters UFOs or aliens in space or on the moon, readers will be like, “What?” I like stories about strange experiences very much, but it’s a different direction from Space Brothers.

In the same vein, Boogie is now an integral part of my work, but at the beginning of the series, I felt that AI robots were “fake” and I had no plans to include them. However, as the series continued, AI and robot technology evolved, and I gradually began to think, “In the time of Mutta and his friends, it wouldn’t be out of place to have an AI robot that could talk like that.”

Interviewer: Indeed, looking at the robots that are being researched and developed by various companies, it seems that in Mutta’s time, robots like Boogie will be commonplace.

Koyama: With such robots, you could run around on the moon more freely. In fact, there will be a new robot based on that in volume 39, so please look forward to it.

Interviewer: Really! Is there a particular scene you would like to draw in the future?

Koyama: I’m in the last stage of Space Brothers…I don’t know what else I have to draw…? (Laughs) I’d like to have one big drama for the ending, but I don’t have a detailed plan, so I don’t know how it will turn out until I actually start drawing it.

I have a vague idea for a scene I want to draw. For example, in Volume 27 chapter 259, there was a scene I’d had in mind from the early stages, when Serika cries after successfully completing the ALS experiment. I thought it would make a good picture if there were tears drifting around her.

As for future story development, it’s still in that kind of vague image state. As I continue to draw, if I feel, “This scene is really good,” I may expand the story. There’s also the possibility that the series will continue for a long time, even though it’s in the final stages. I really don’t know until I start working on it. But I feel that I’m heading toward the end in a good way.

Interviewer: As of Volume 35, I’m getting a strong feeling that we’re approaching the end of the story!

Koyama: But in reality, it could be that the story ends without a climax…maybe the ending of the story started without the author noticing it. (Laughs)

Interviewer: Huh? (Laughs) Don’t say so, but please make it exciting. I’m looking forward to it!