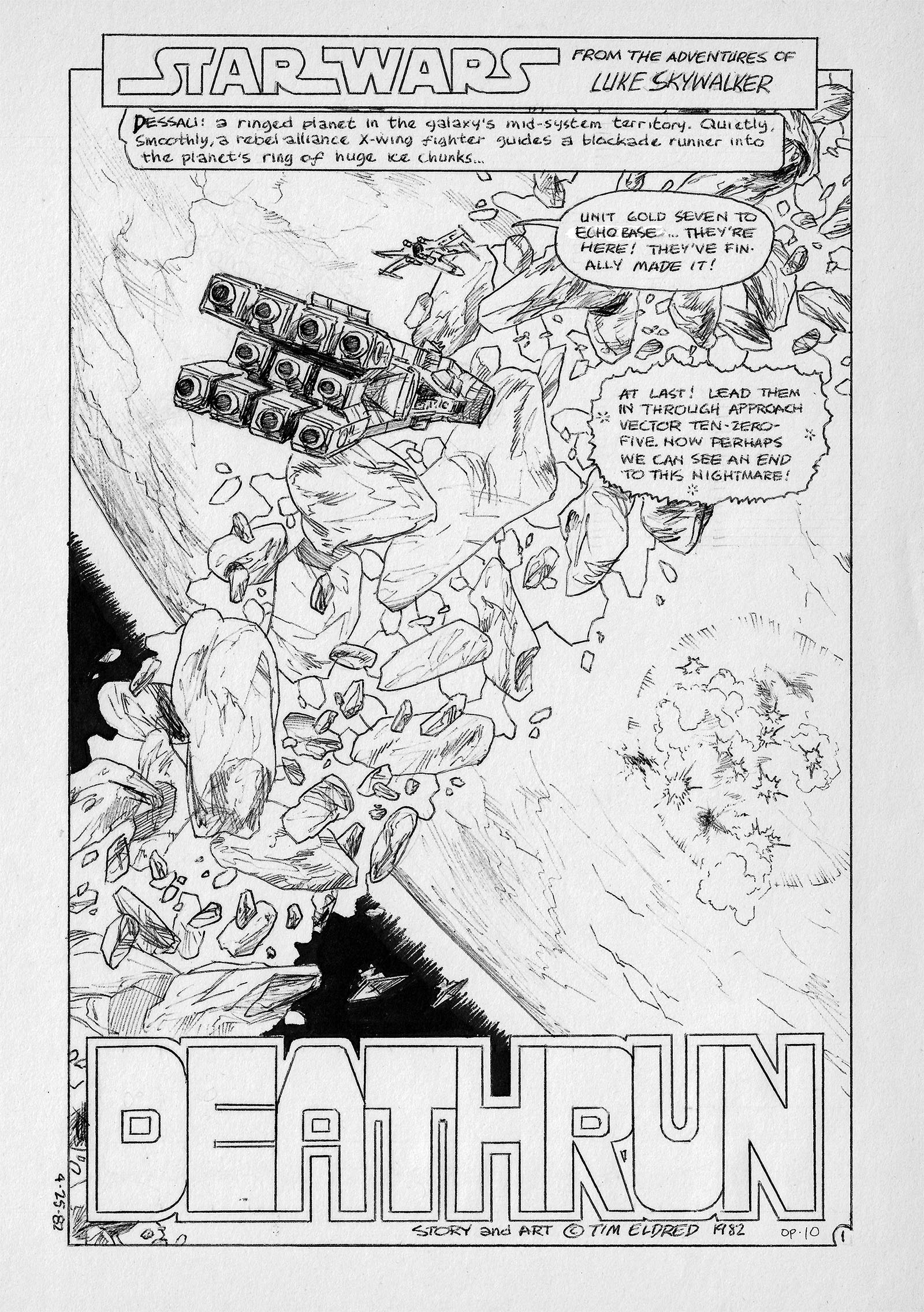

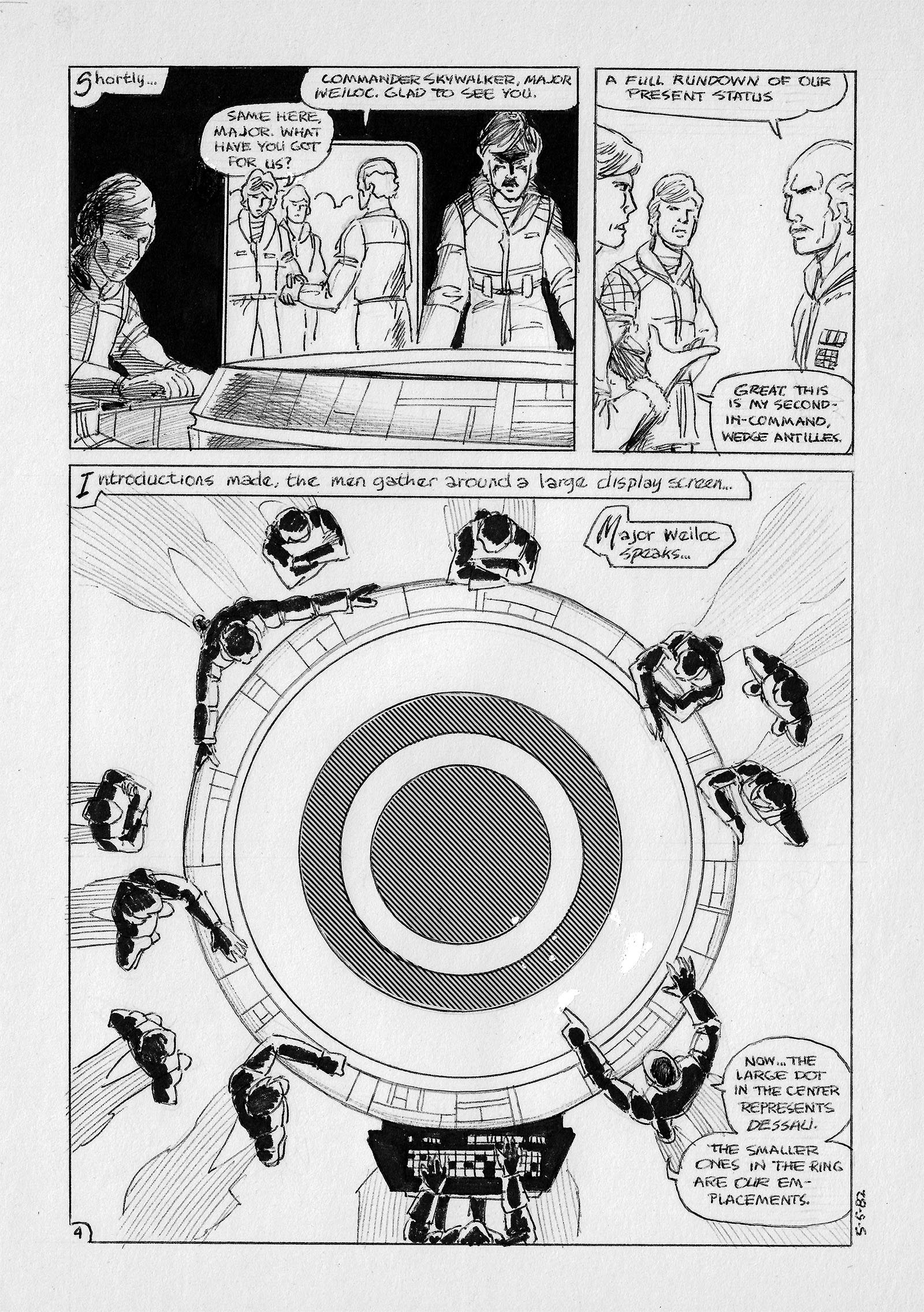

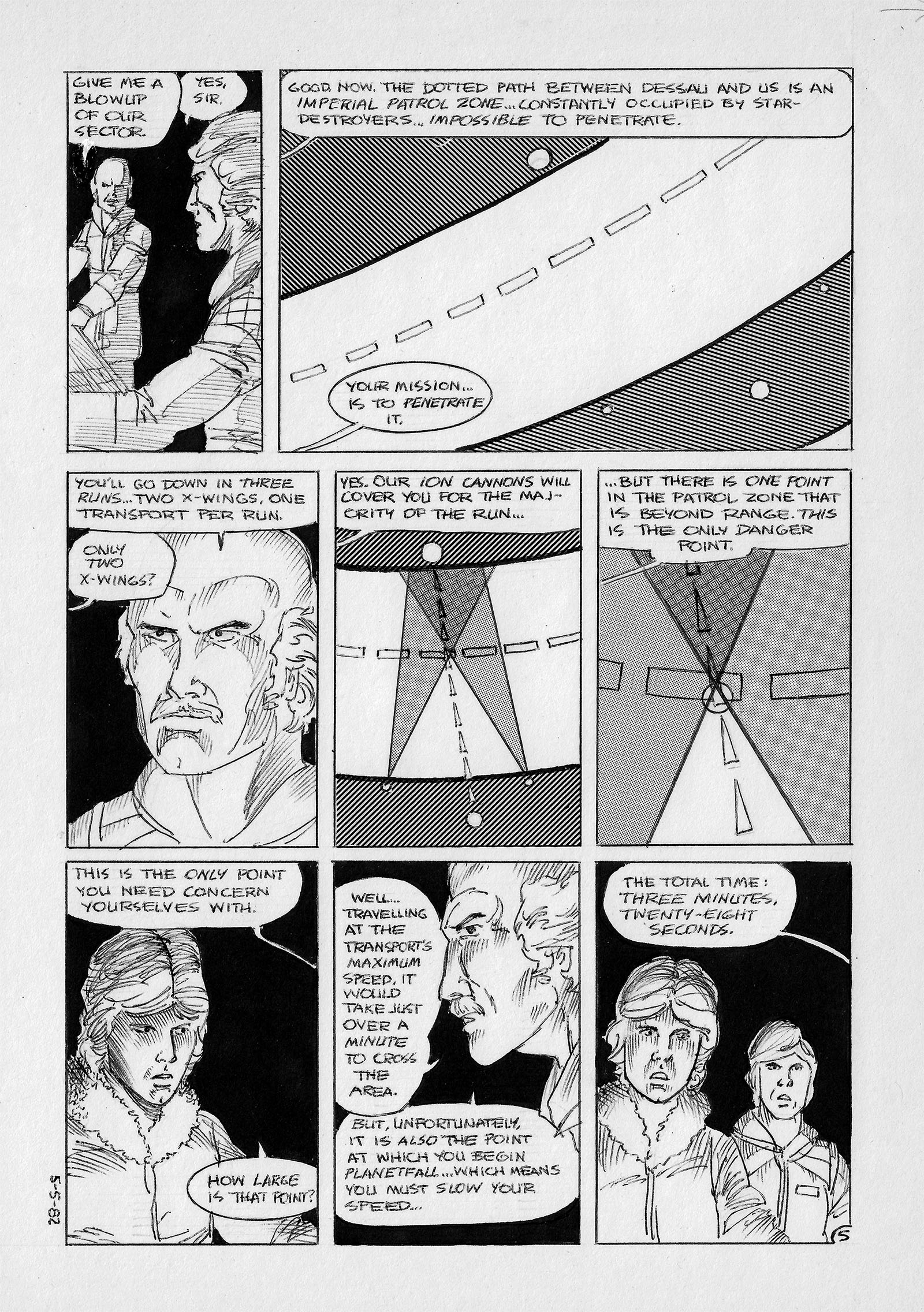

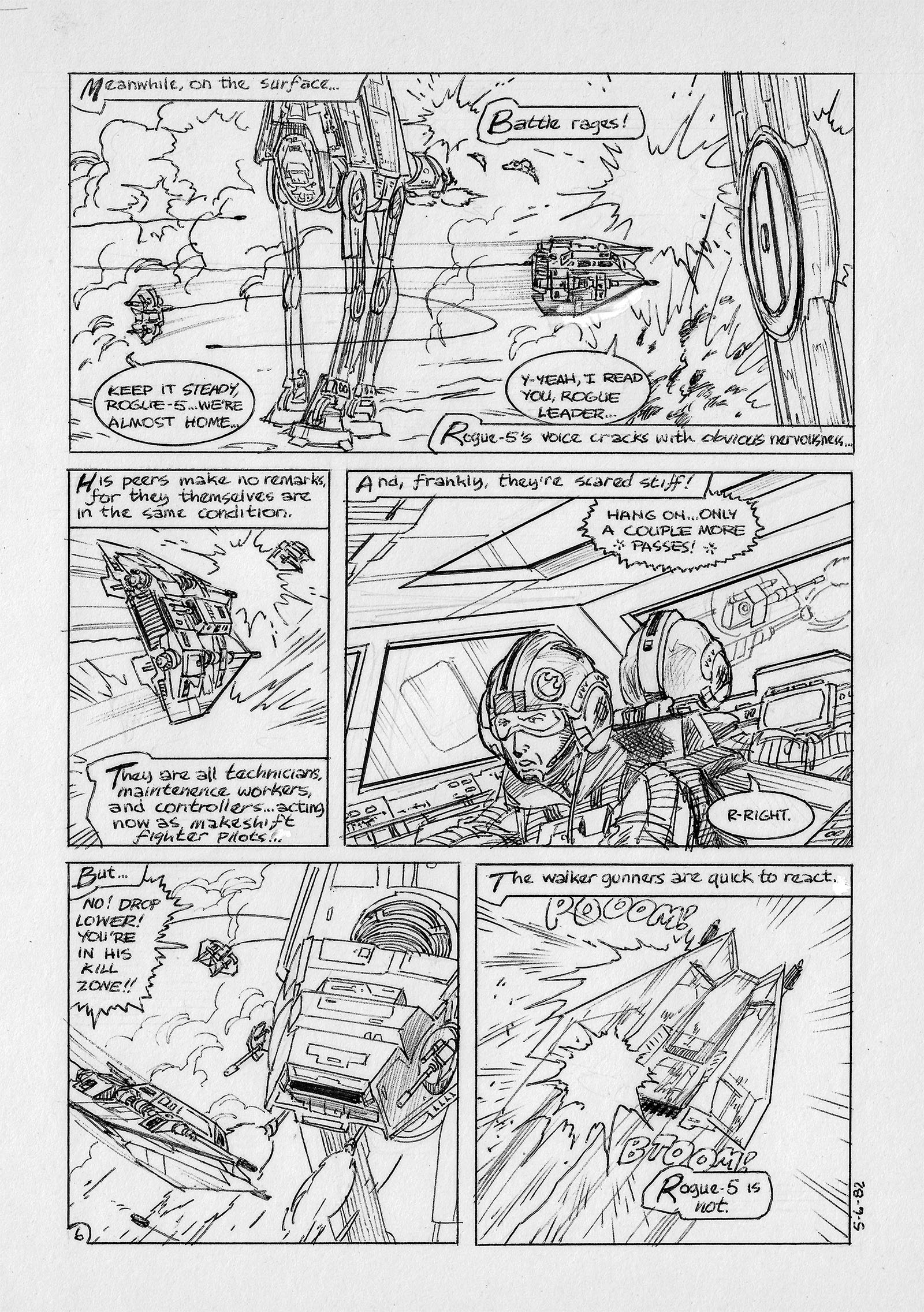

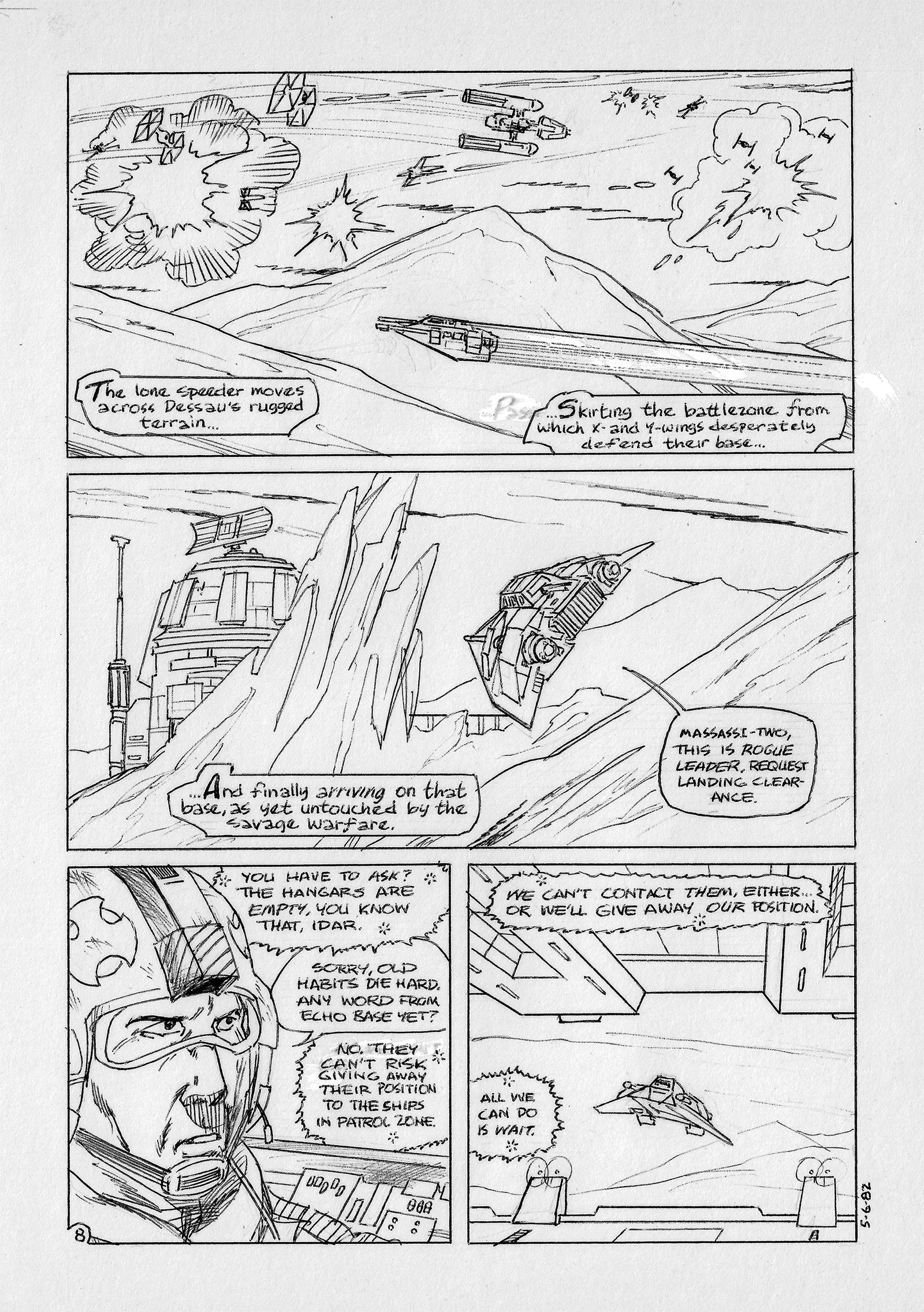

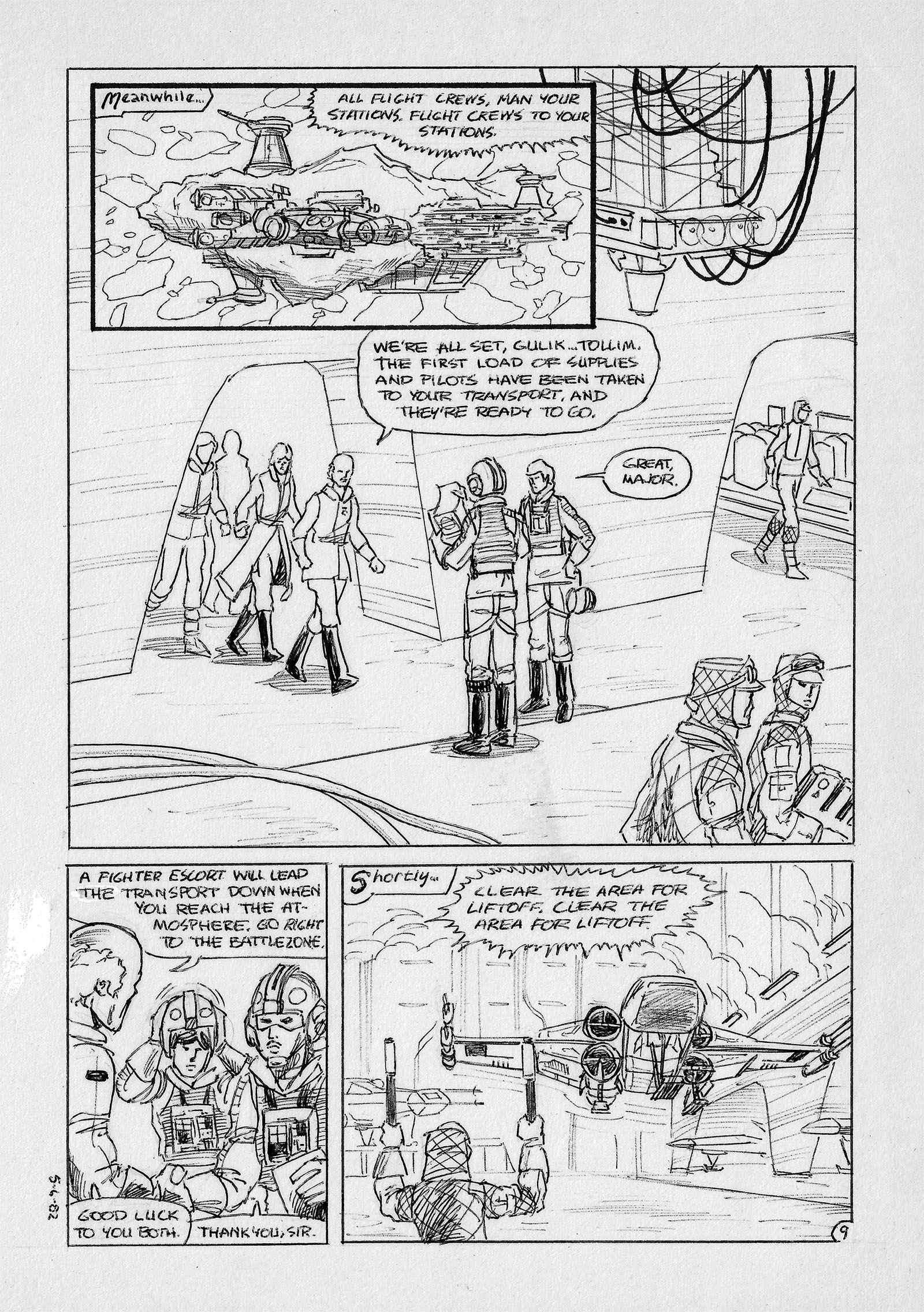

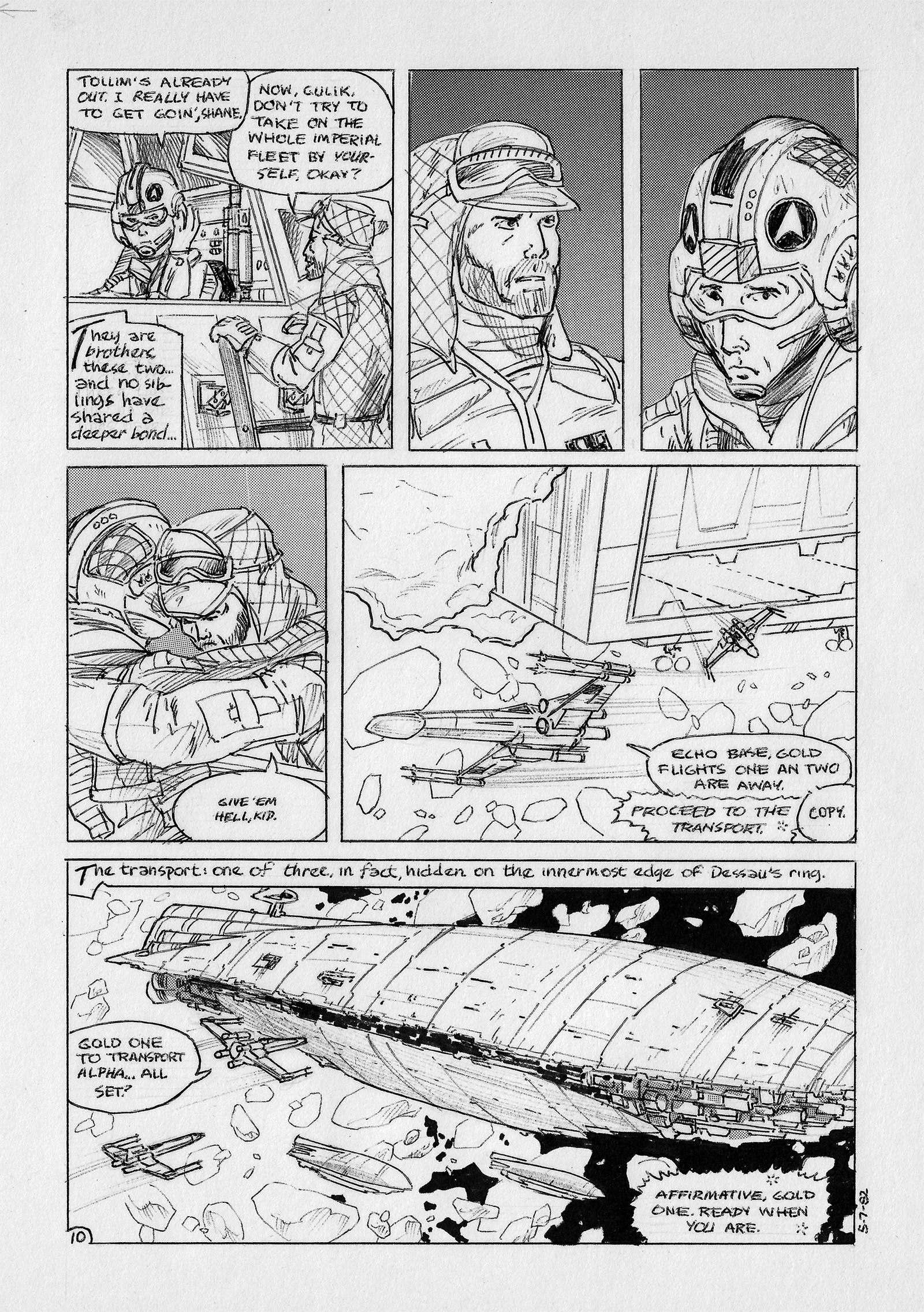

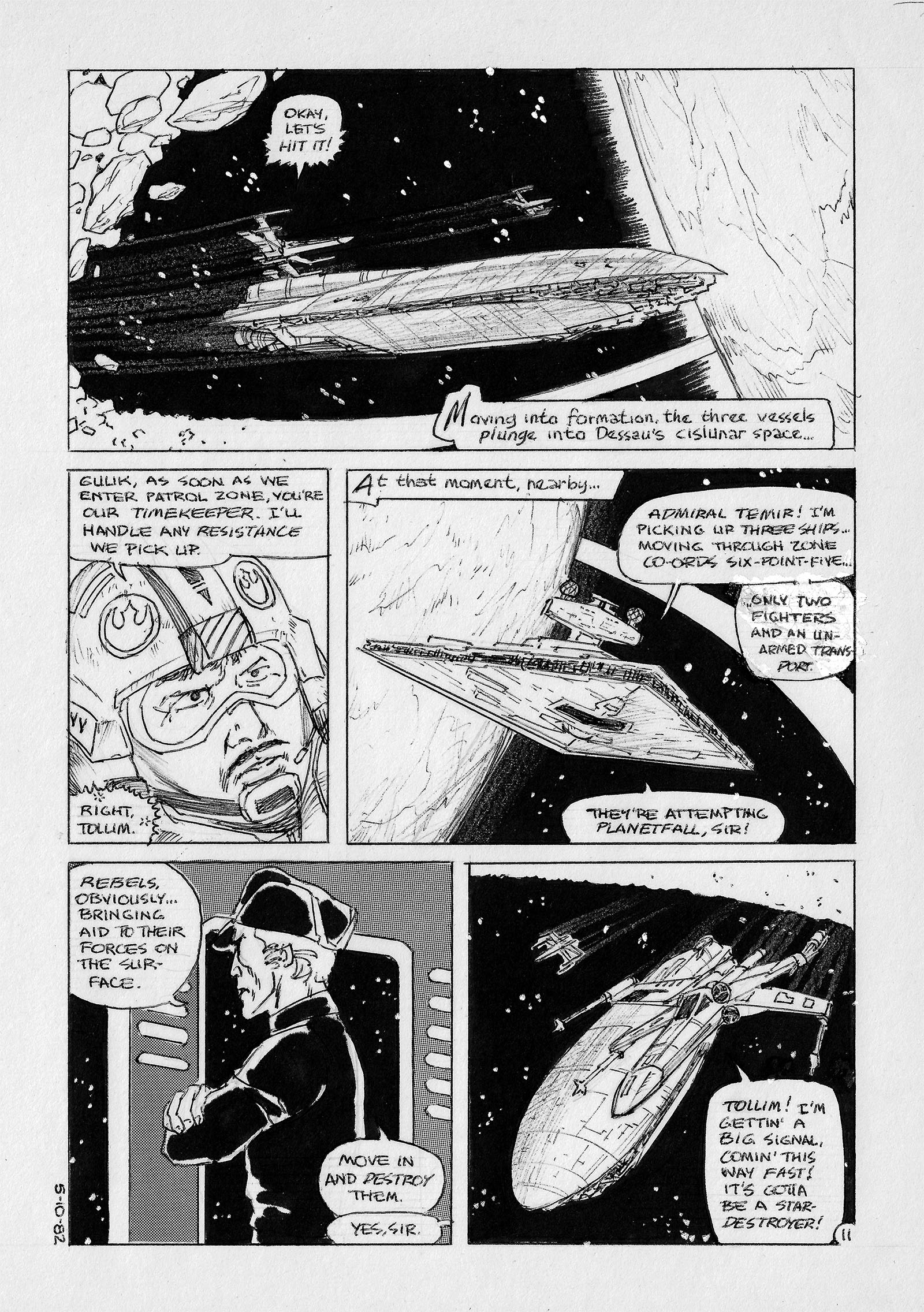

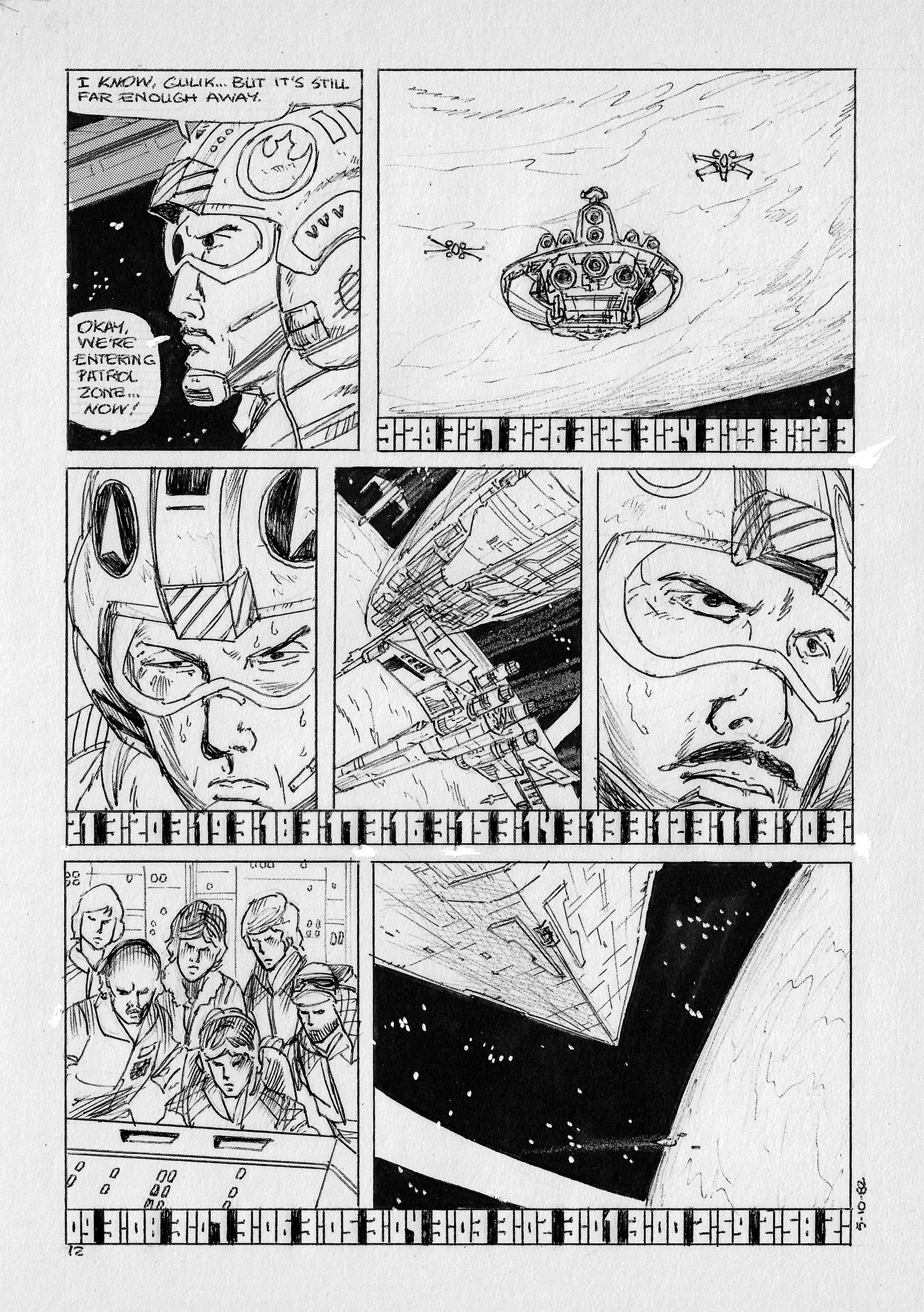

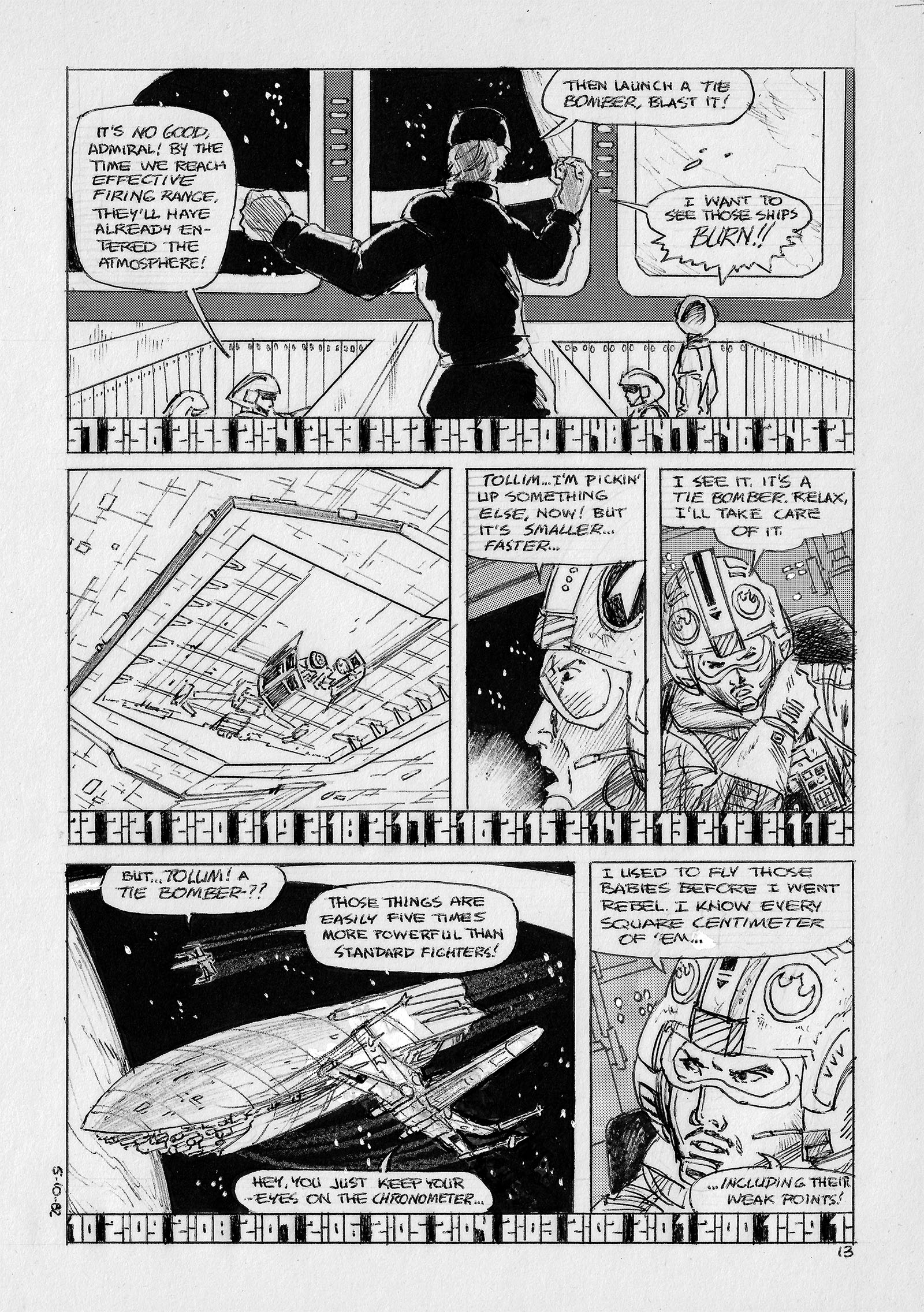

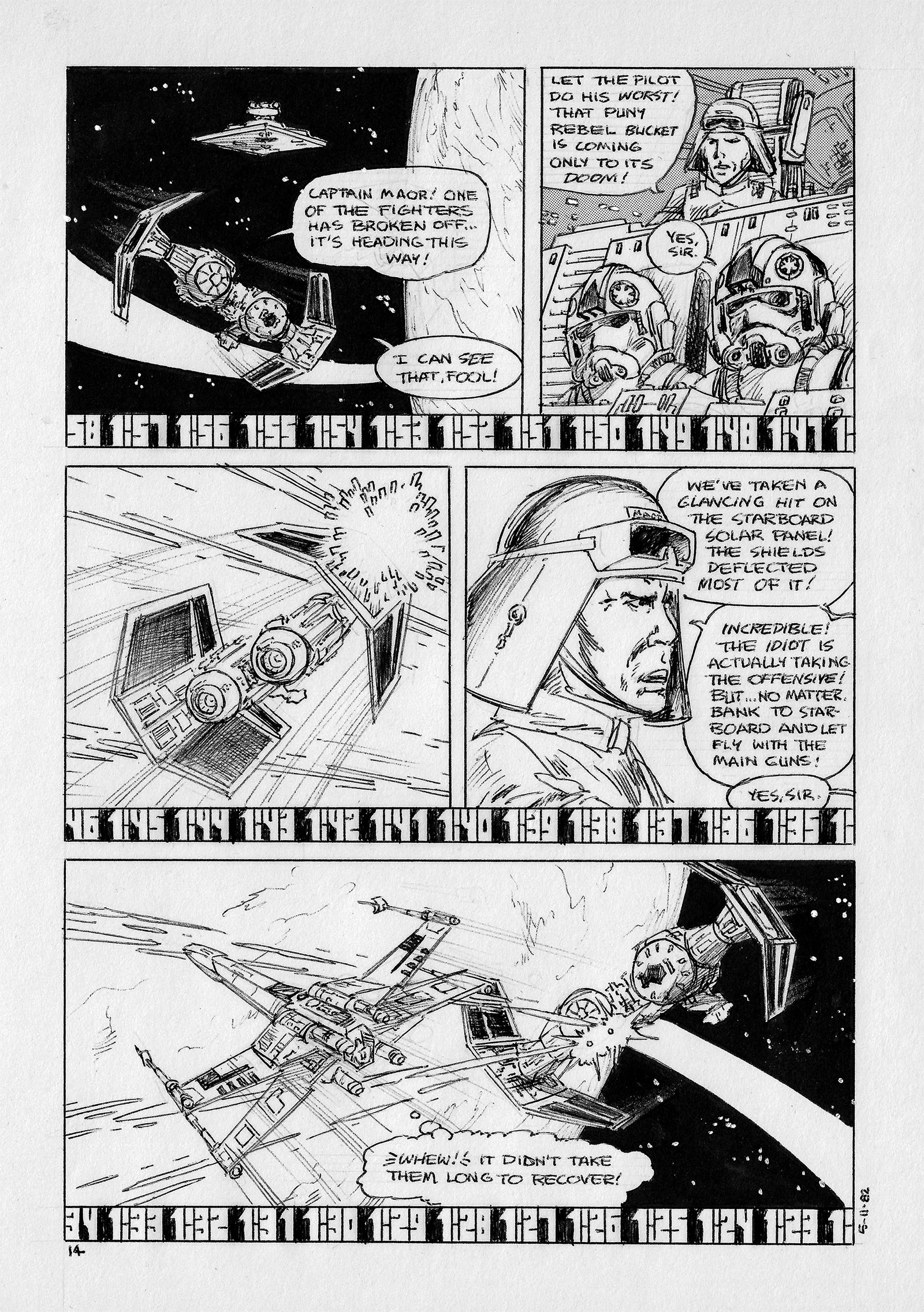

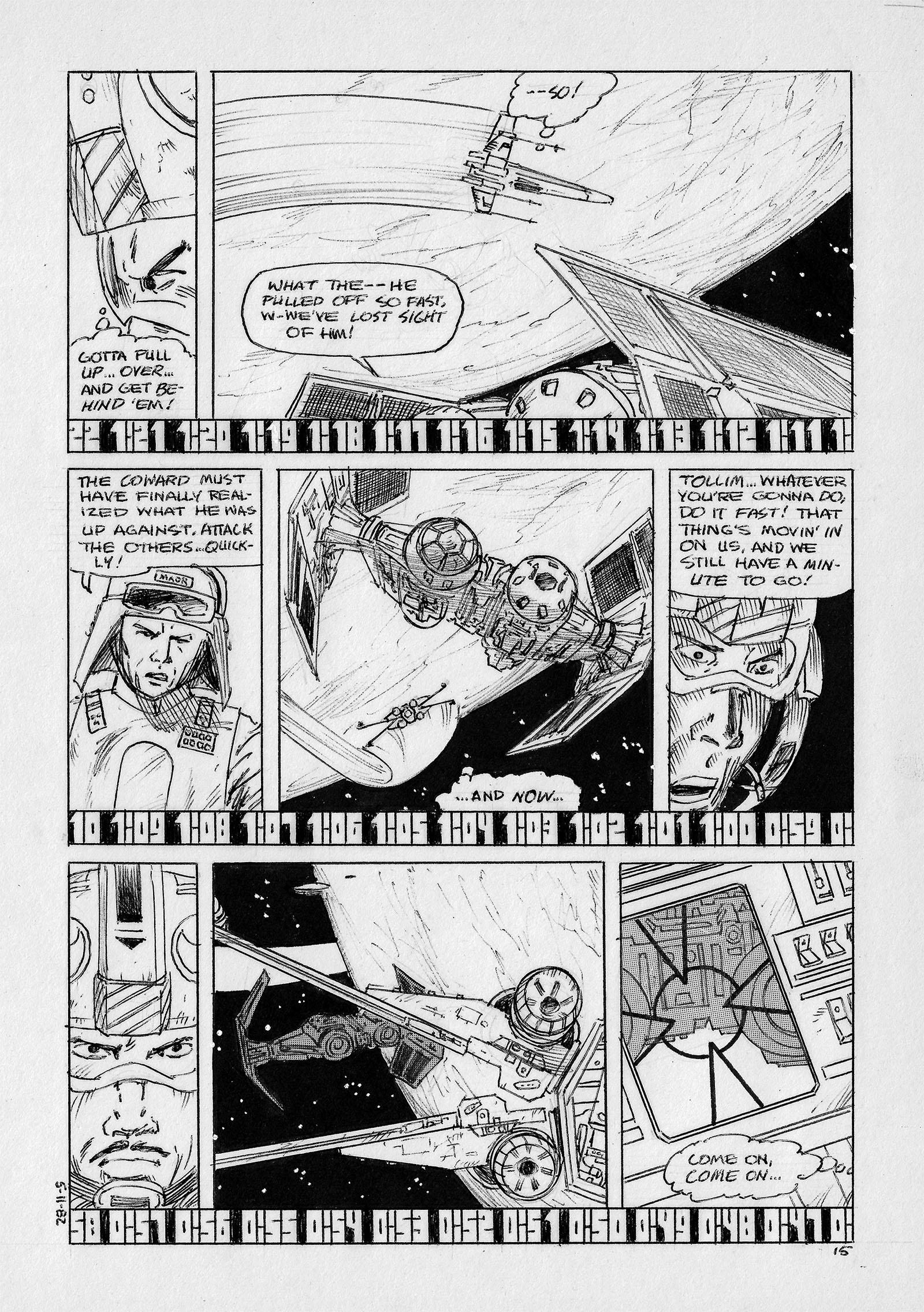

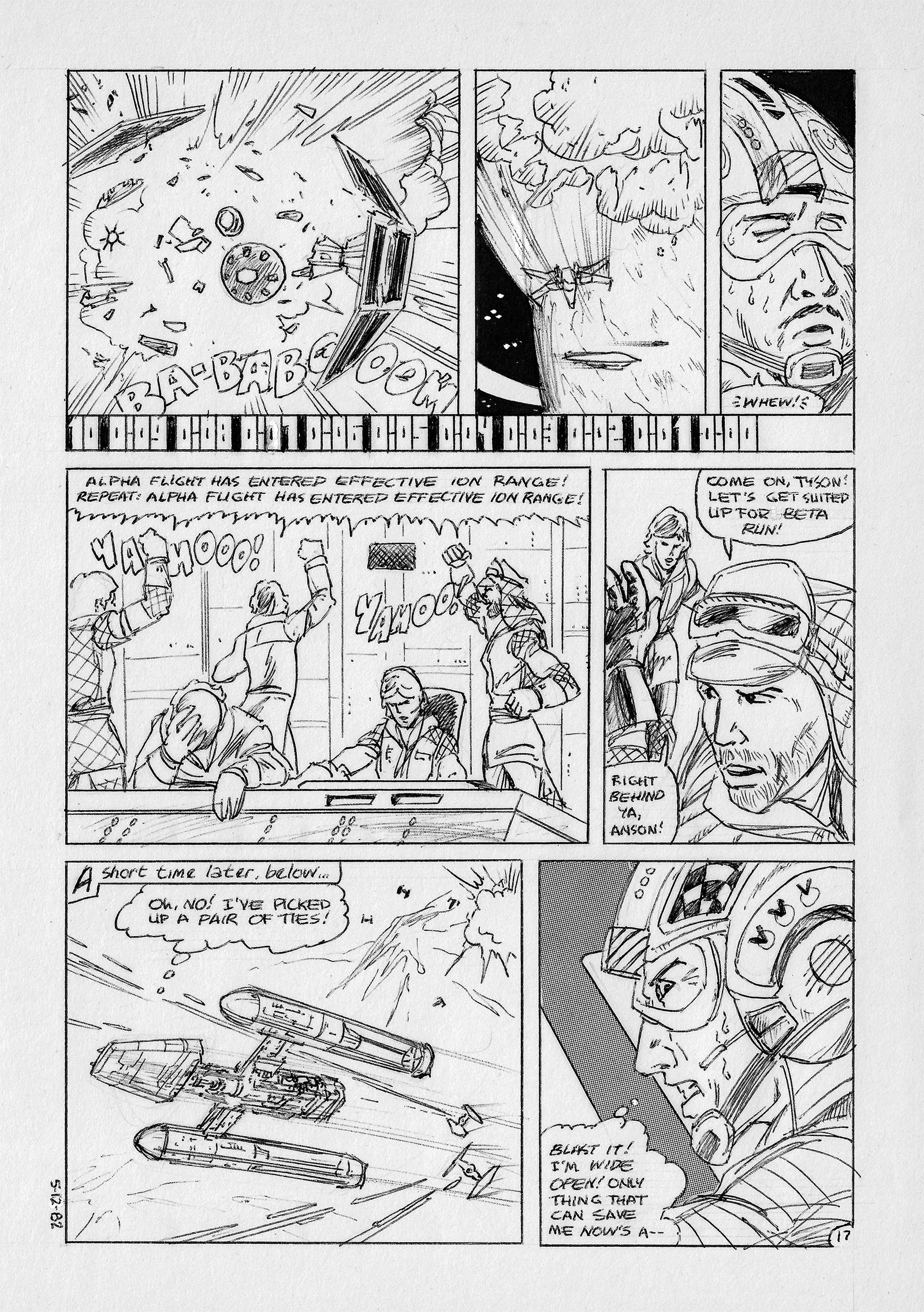

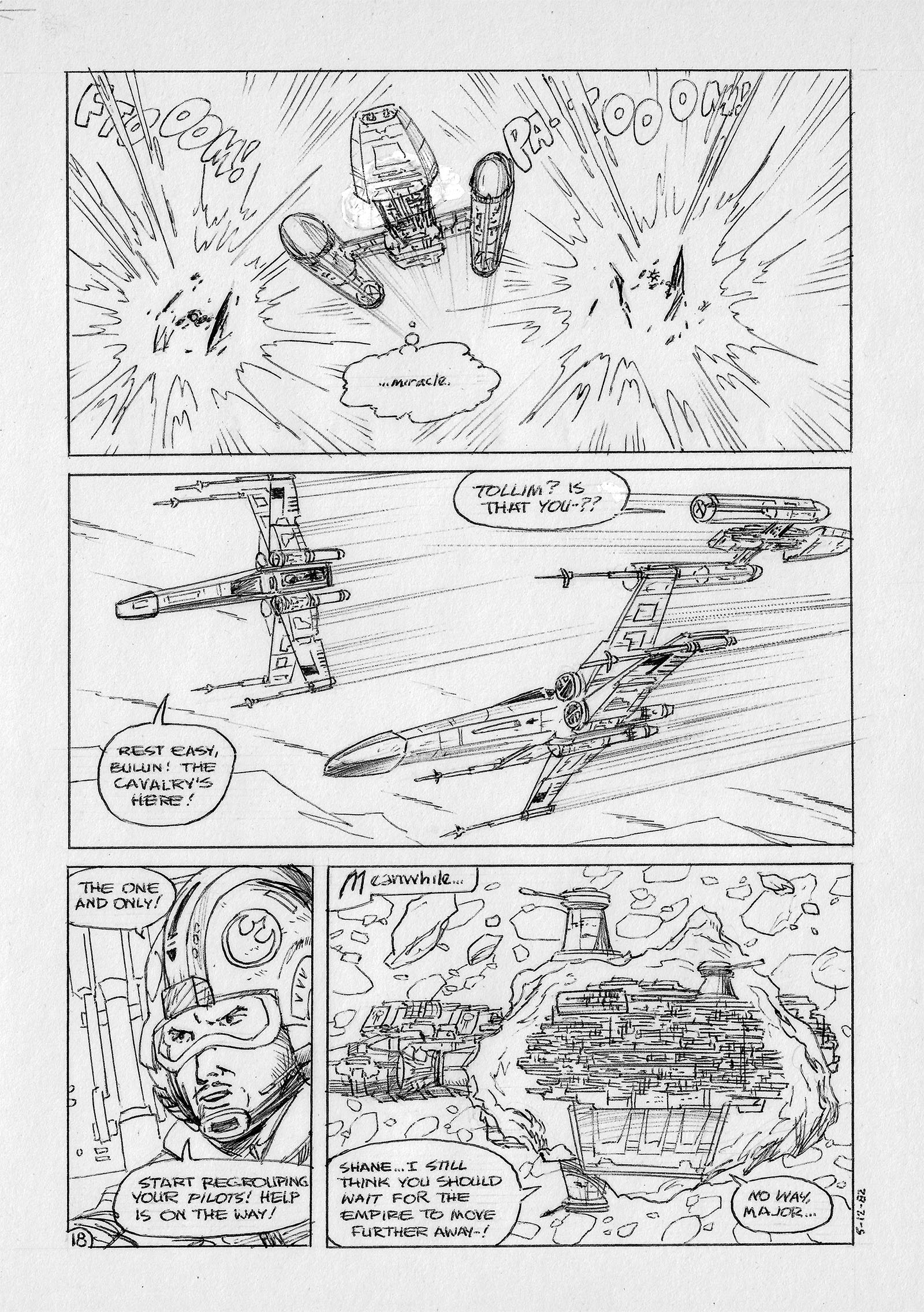

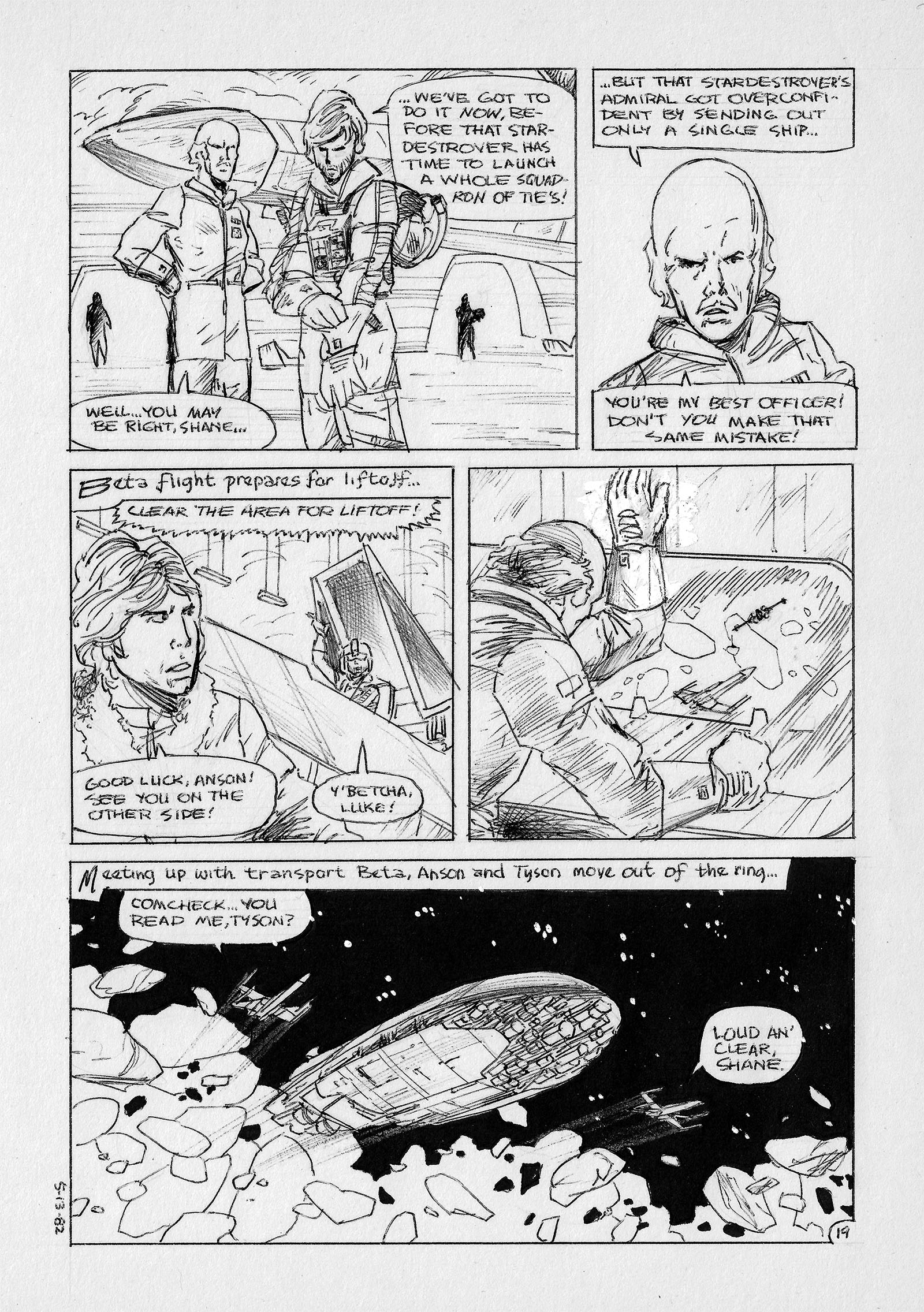

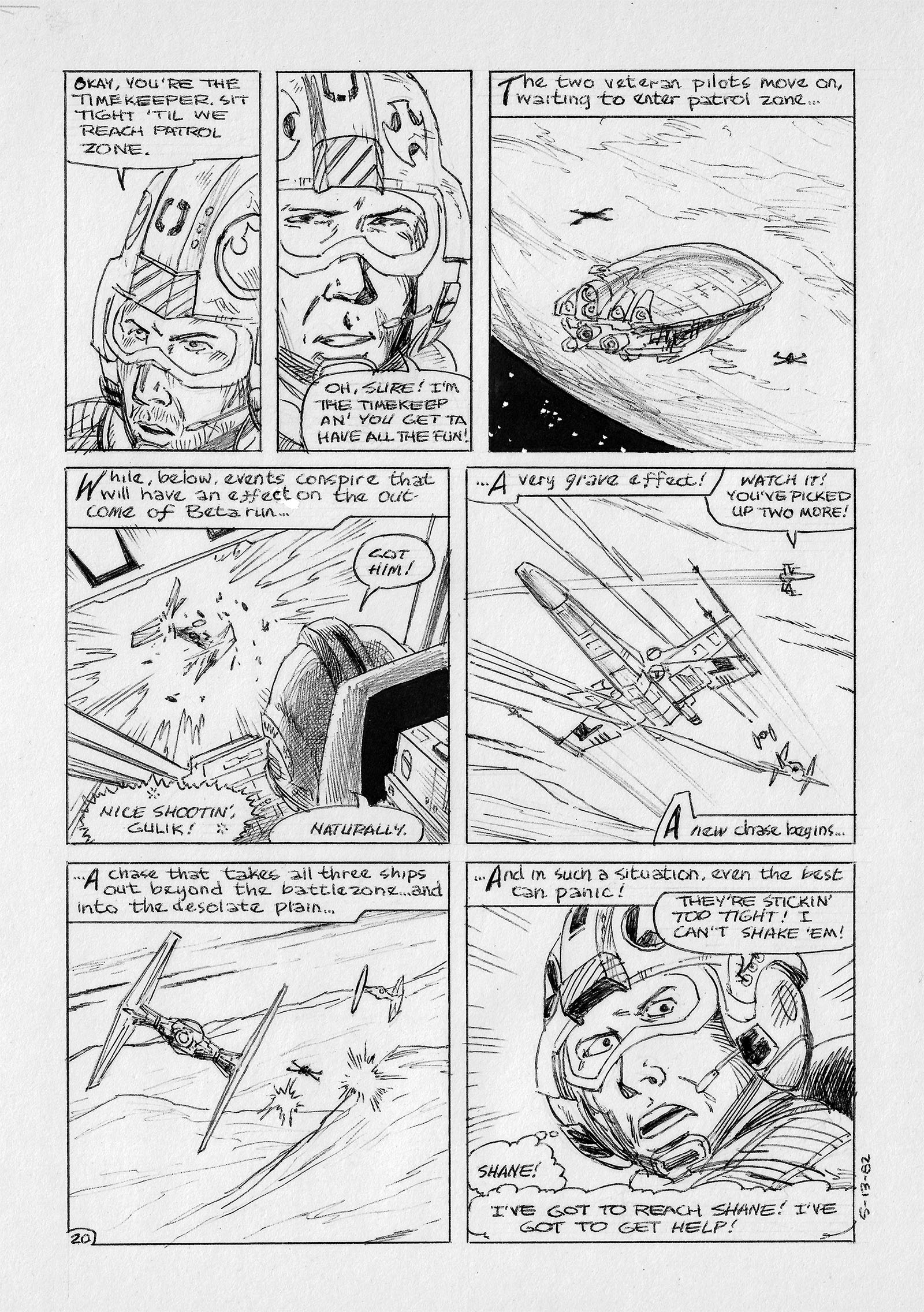

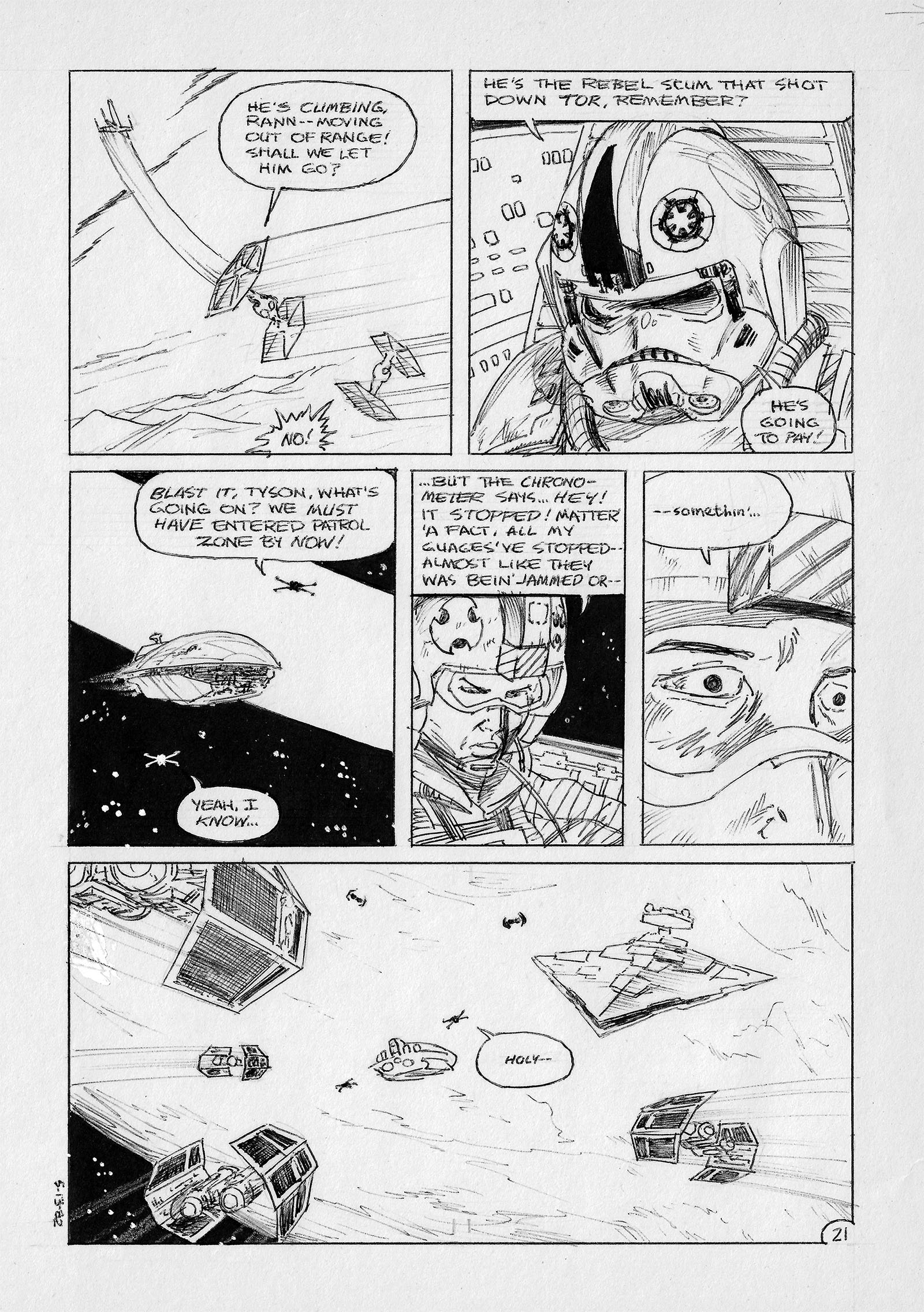

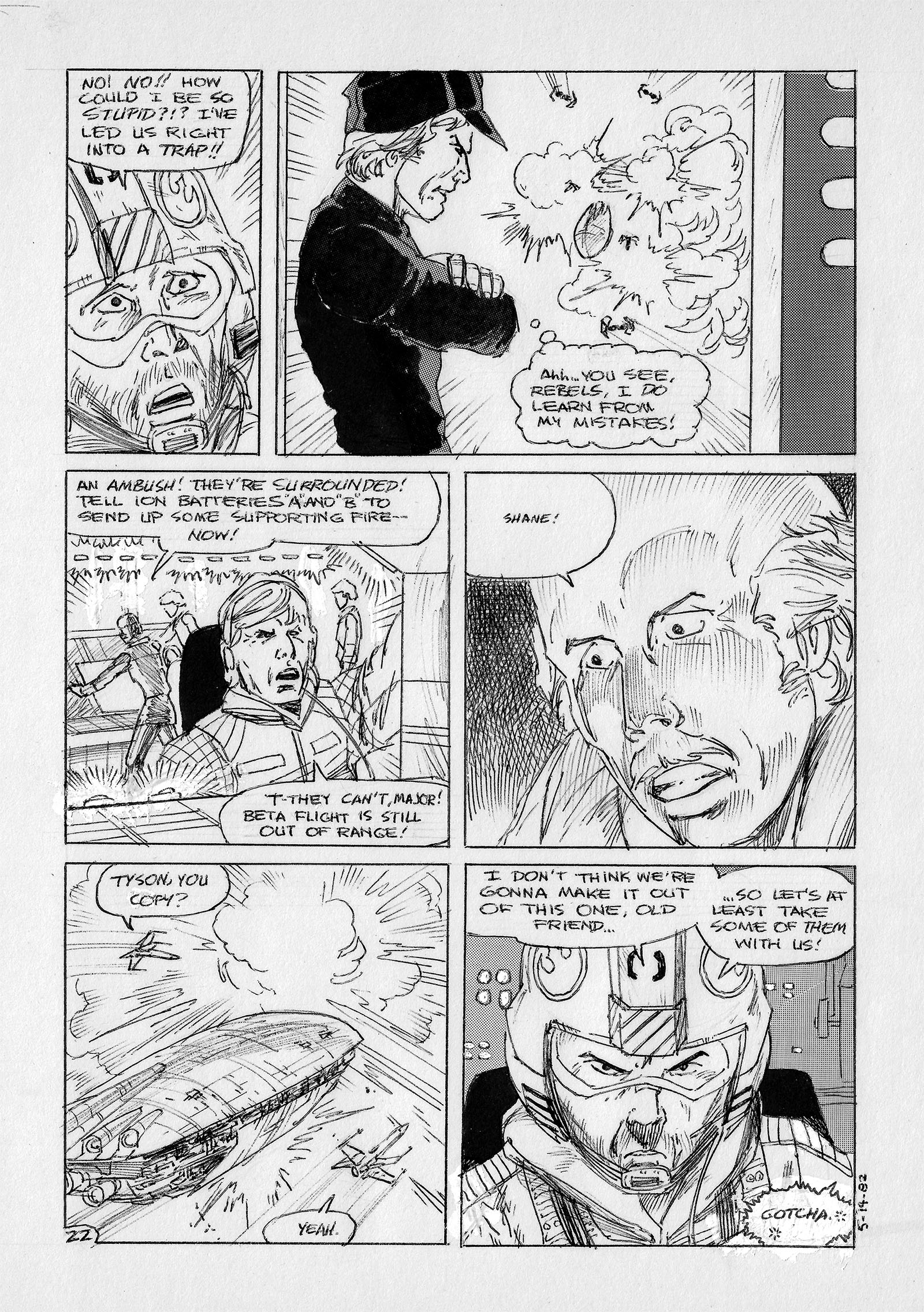

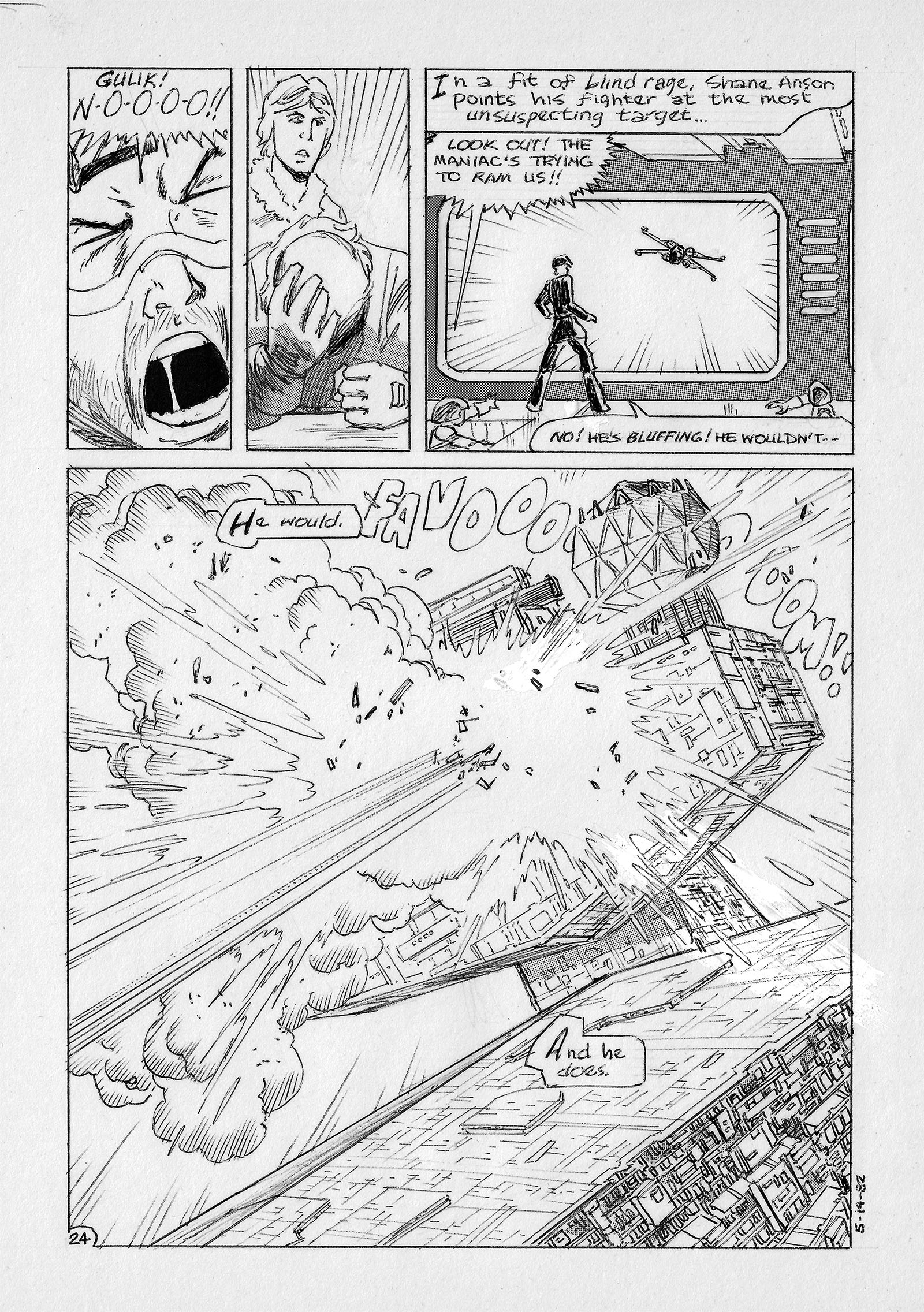

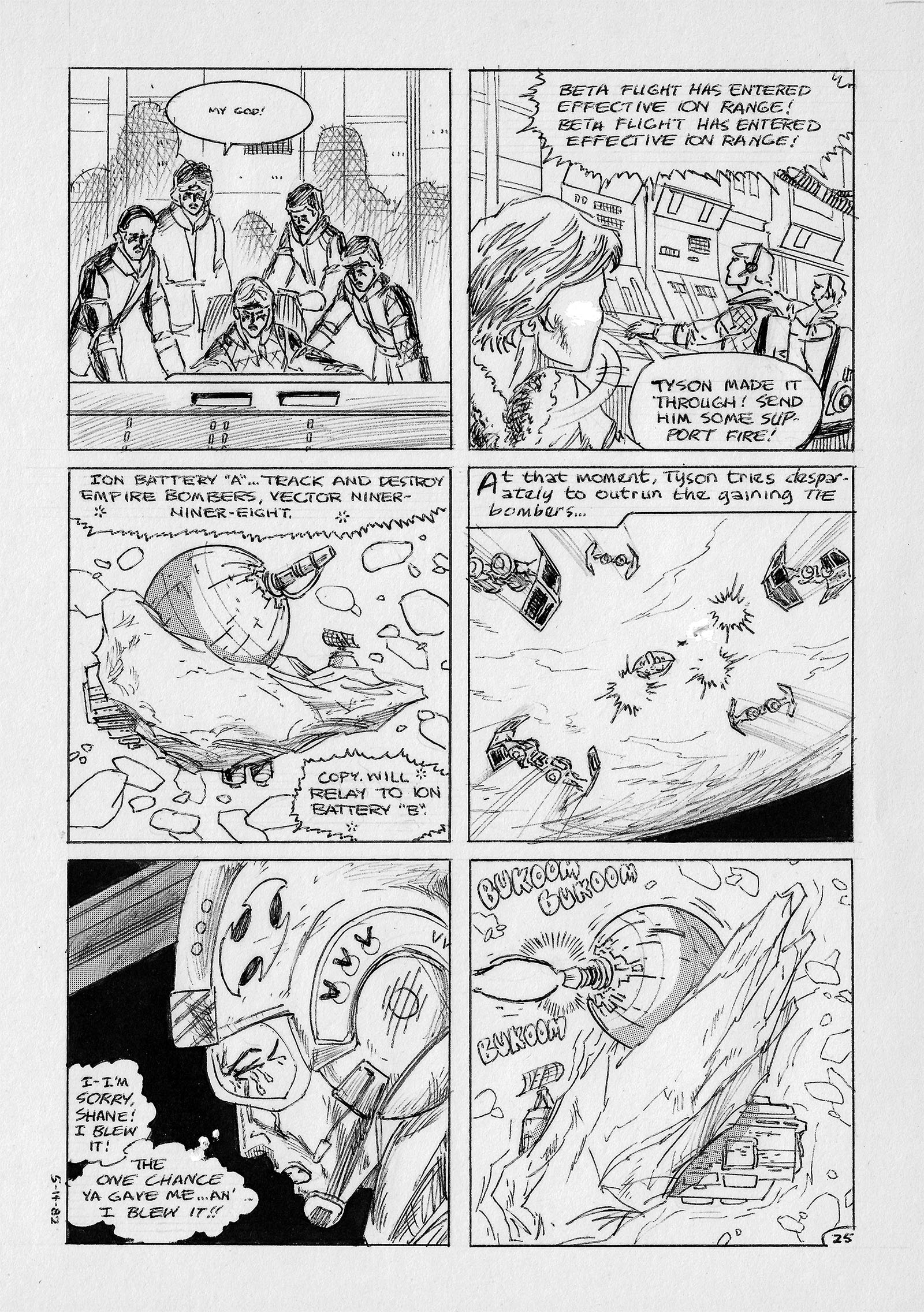

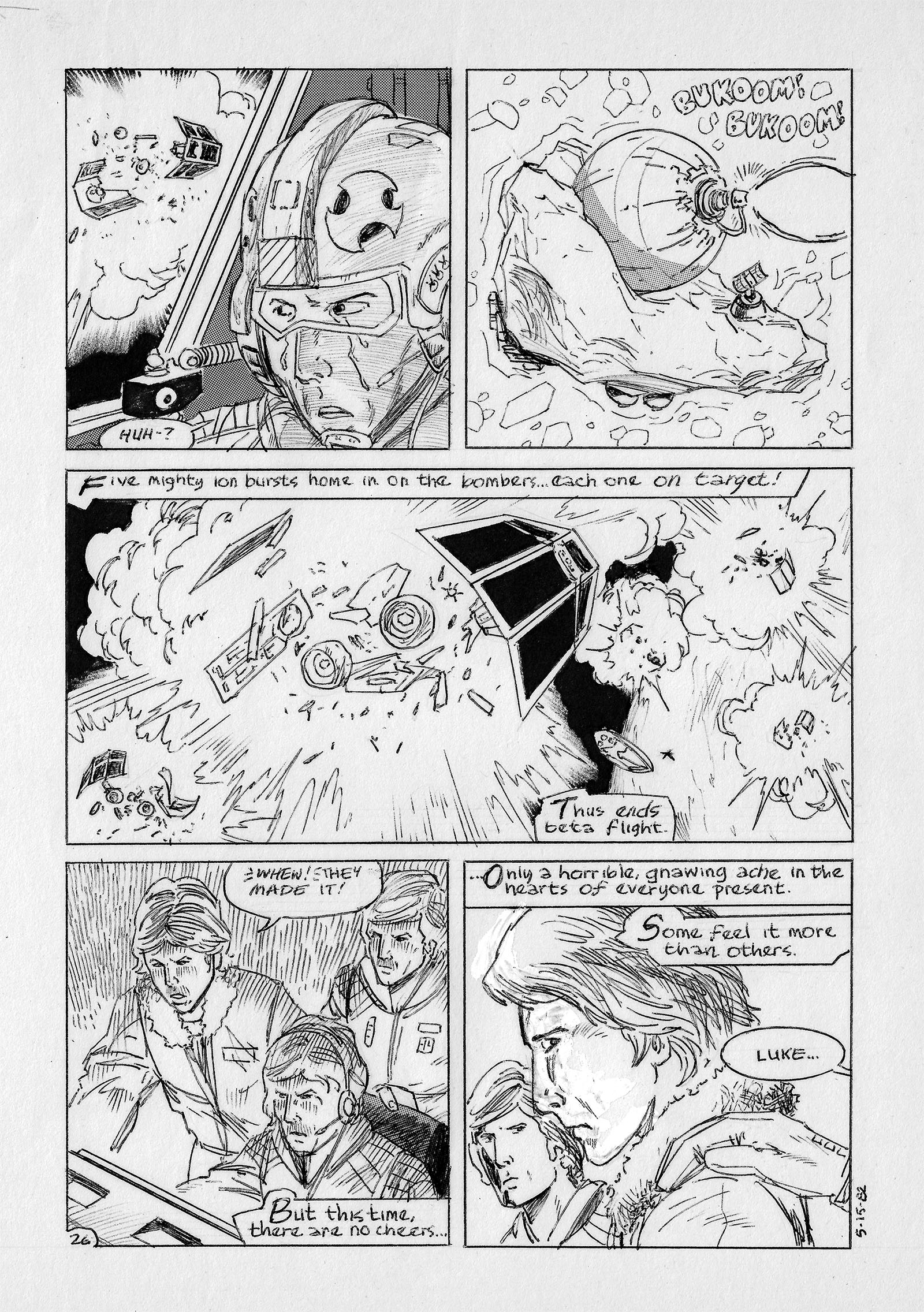

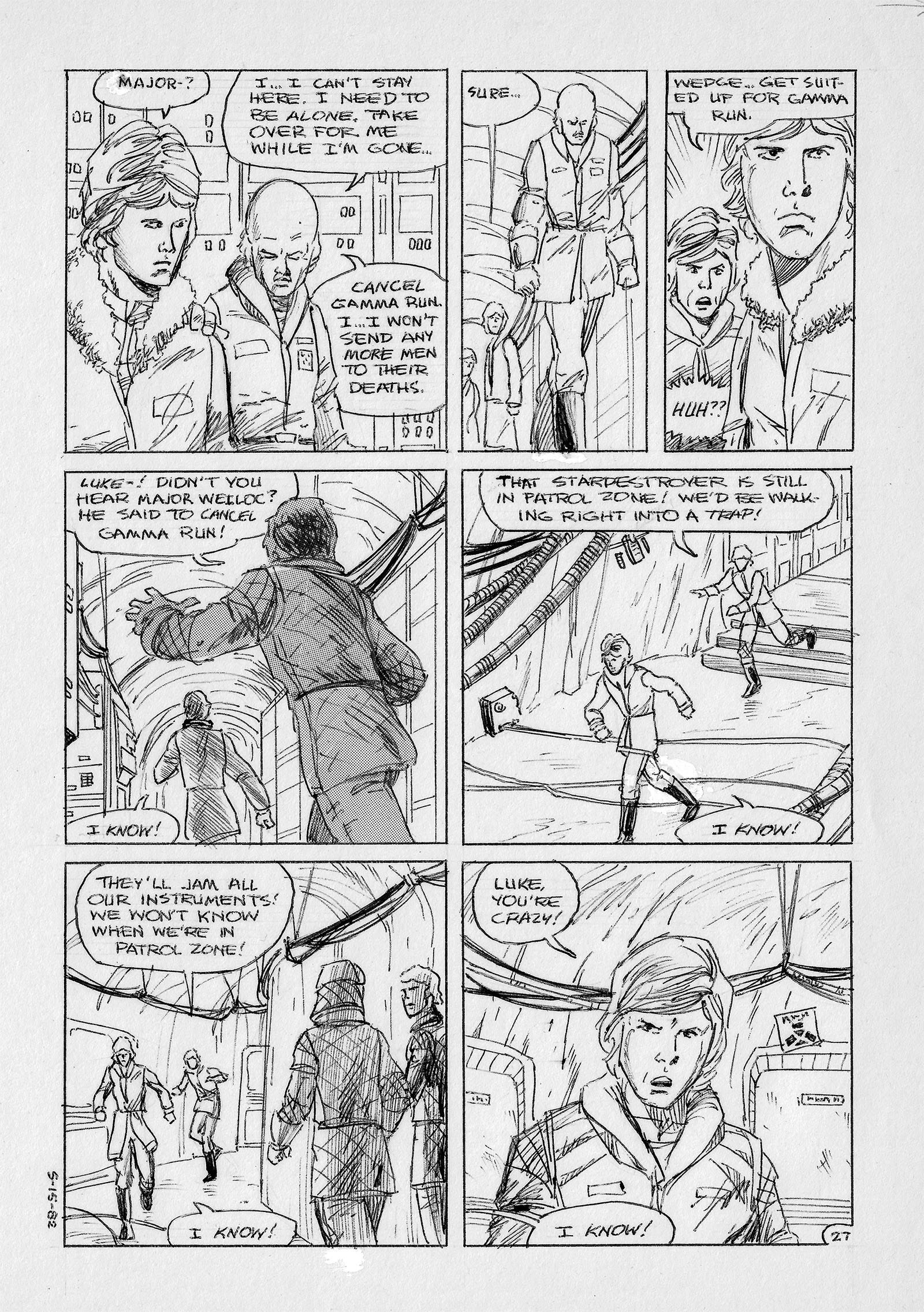

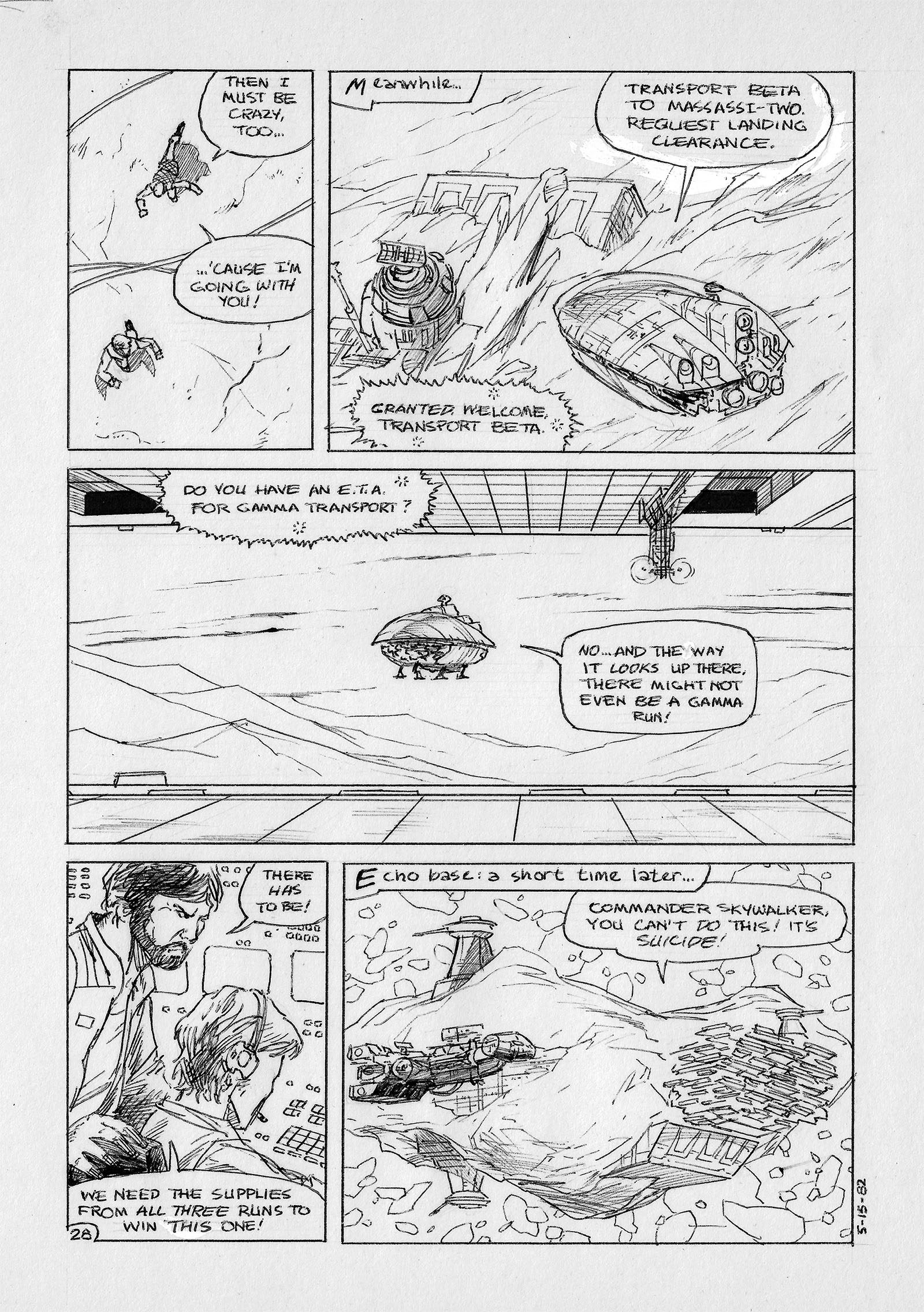

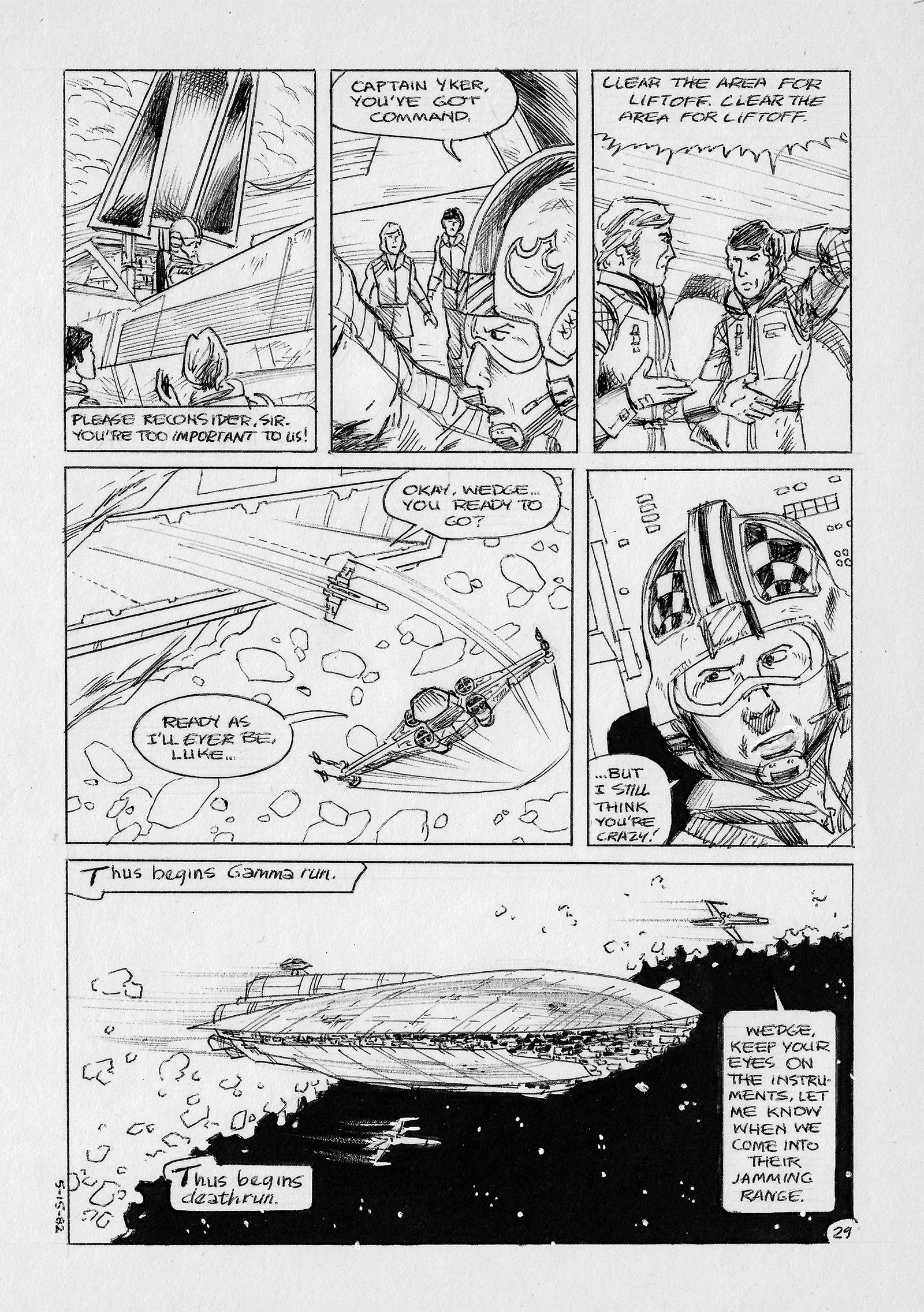

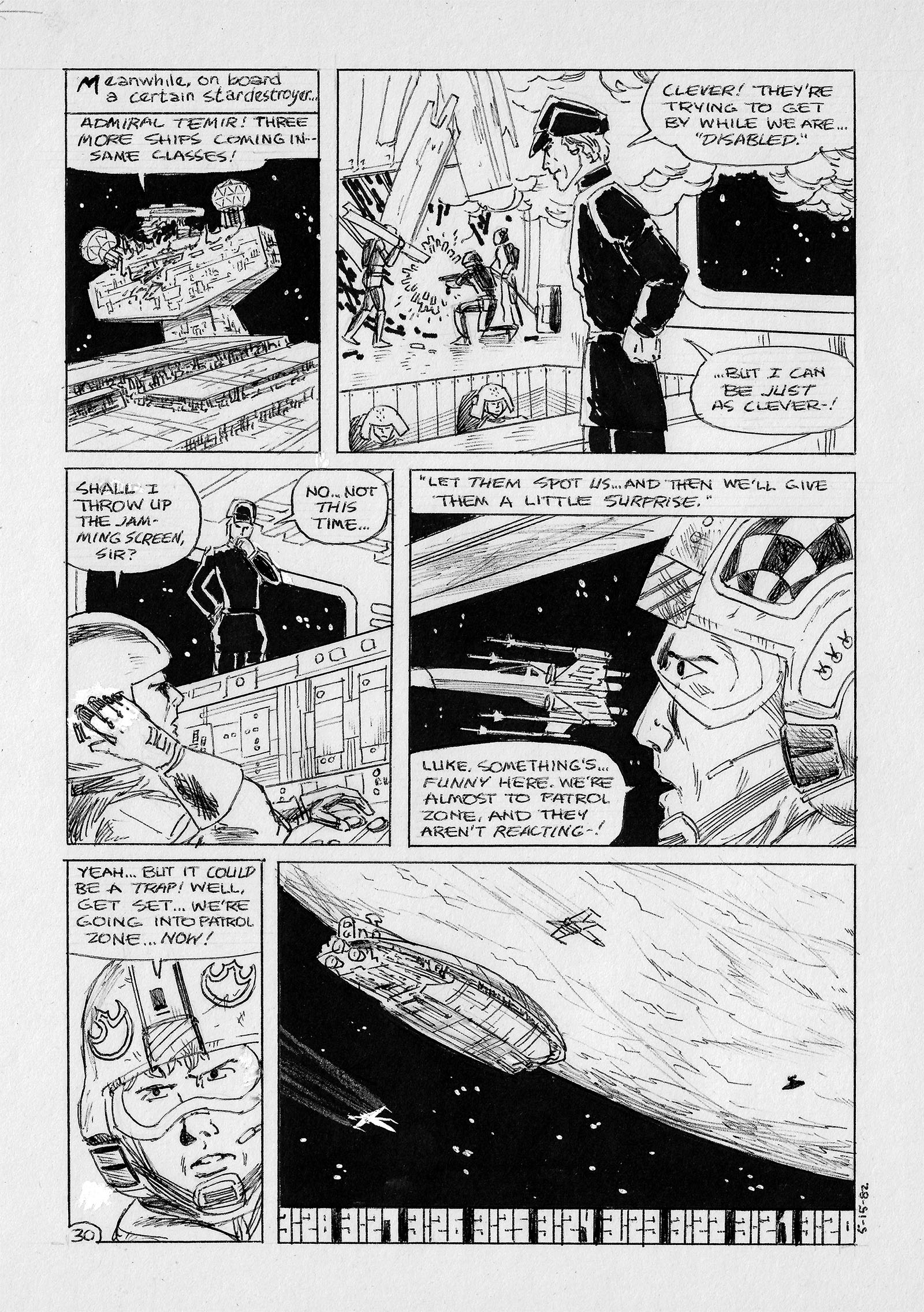

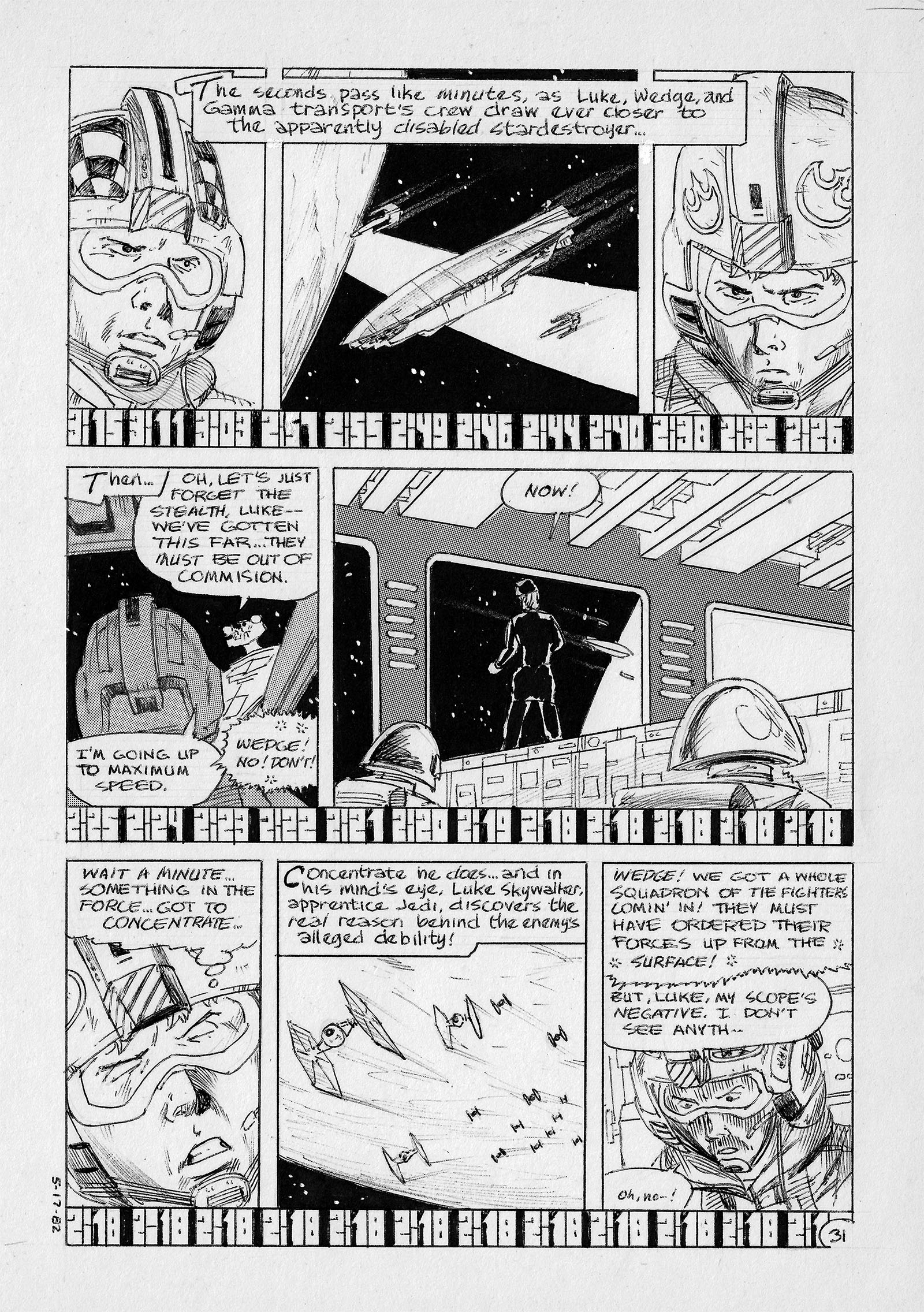

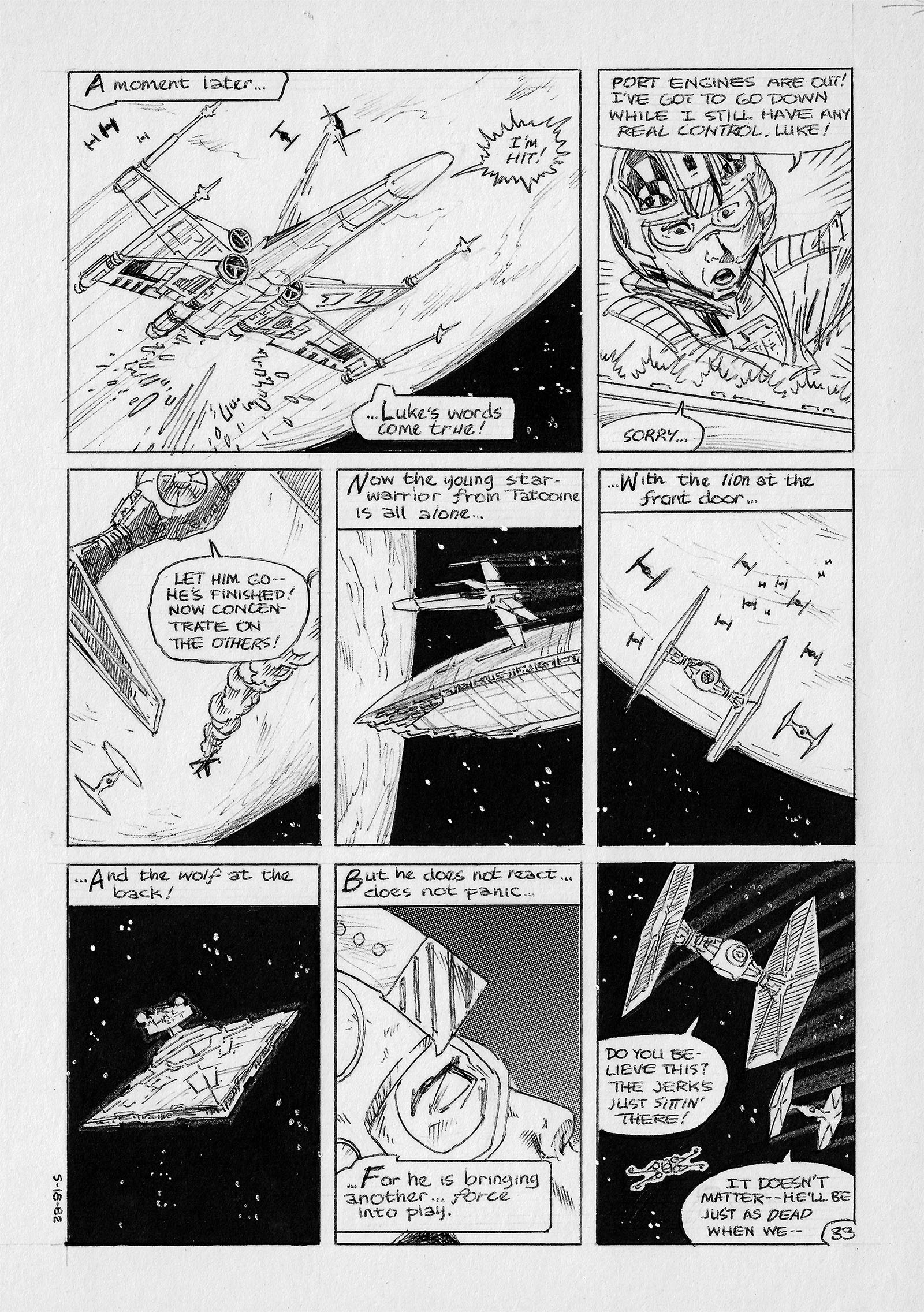

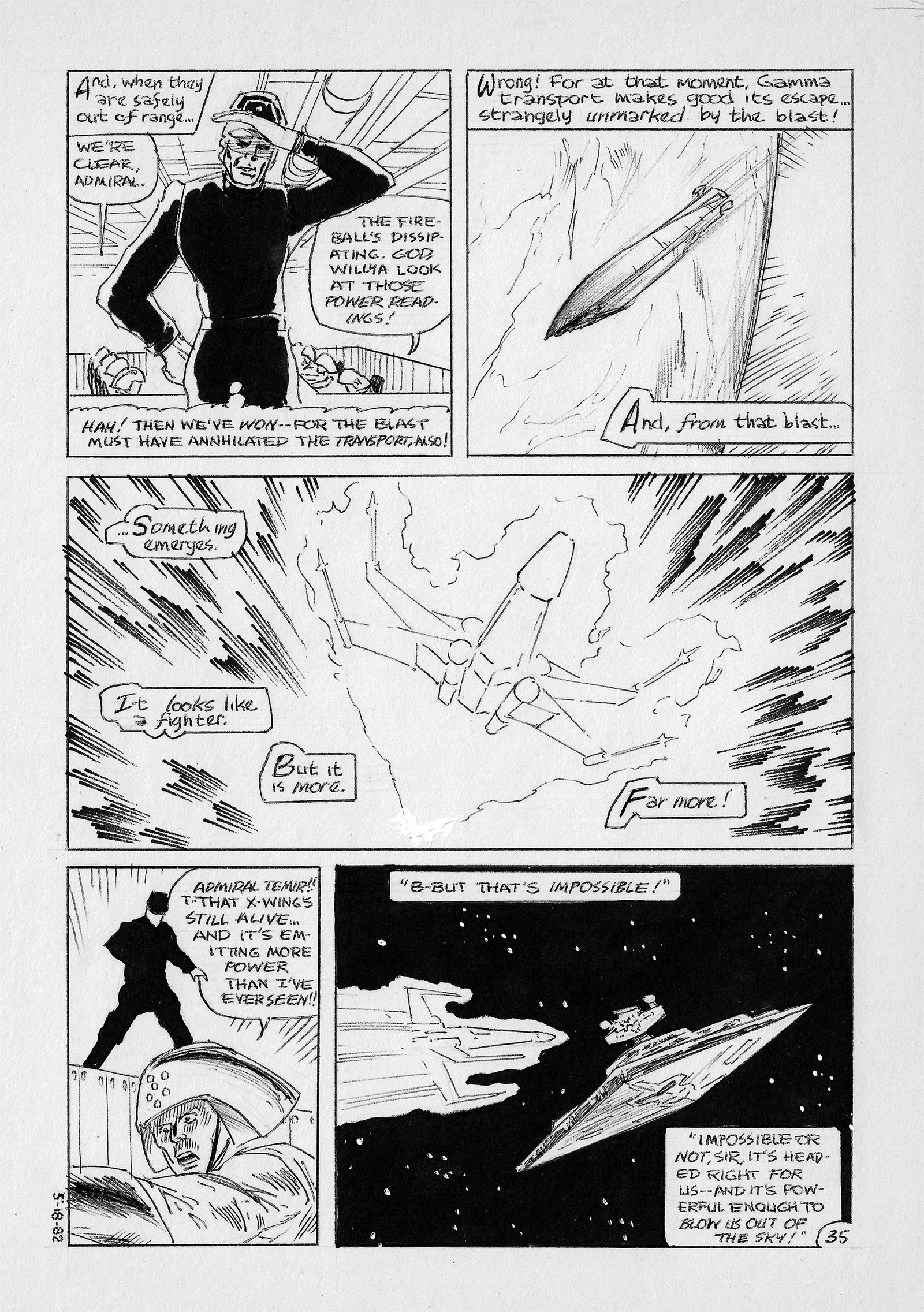

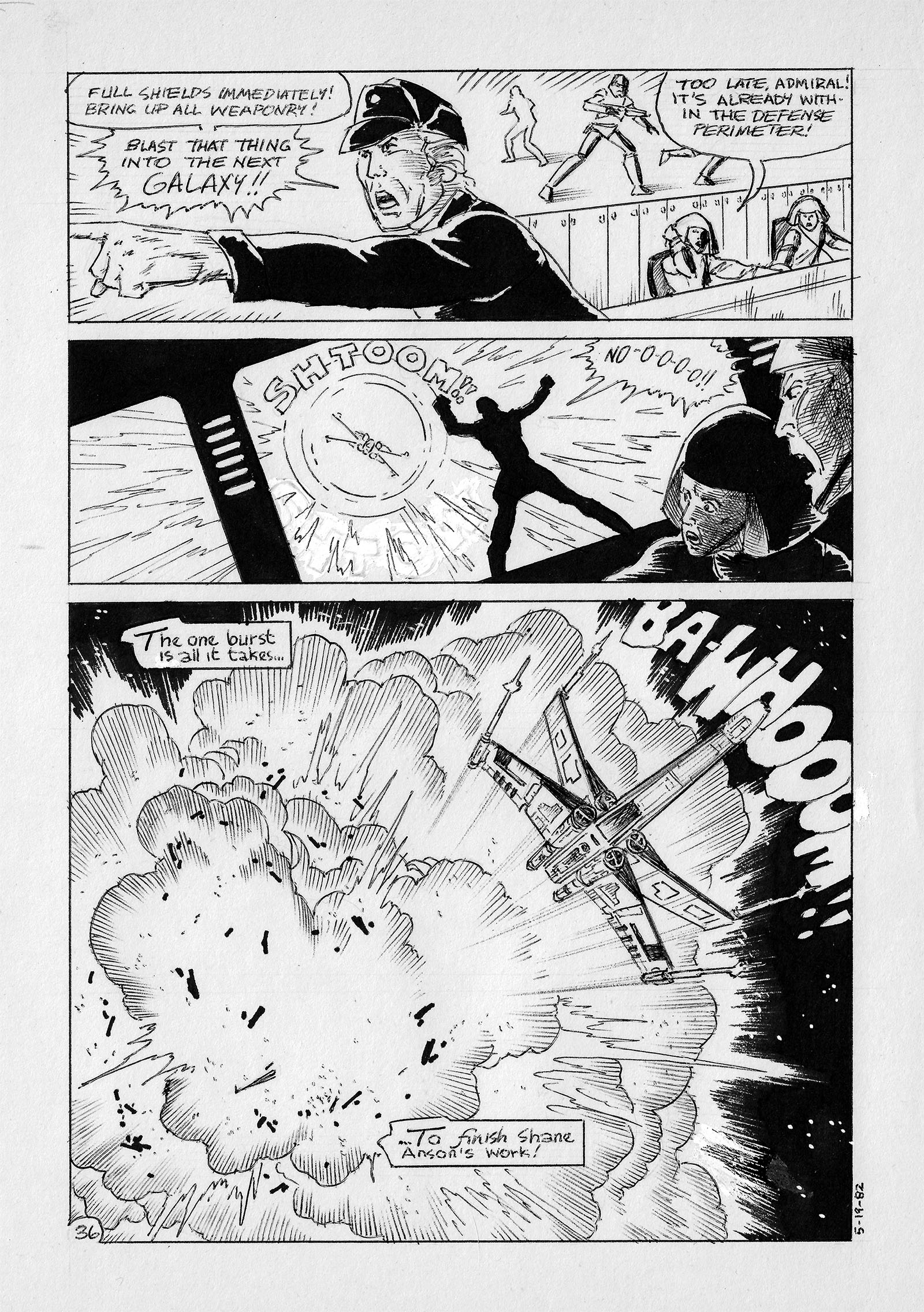

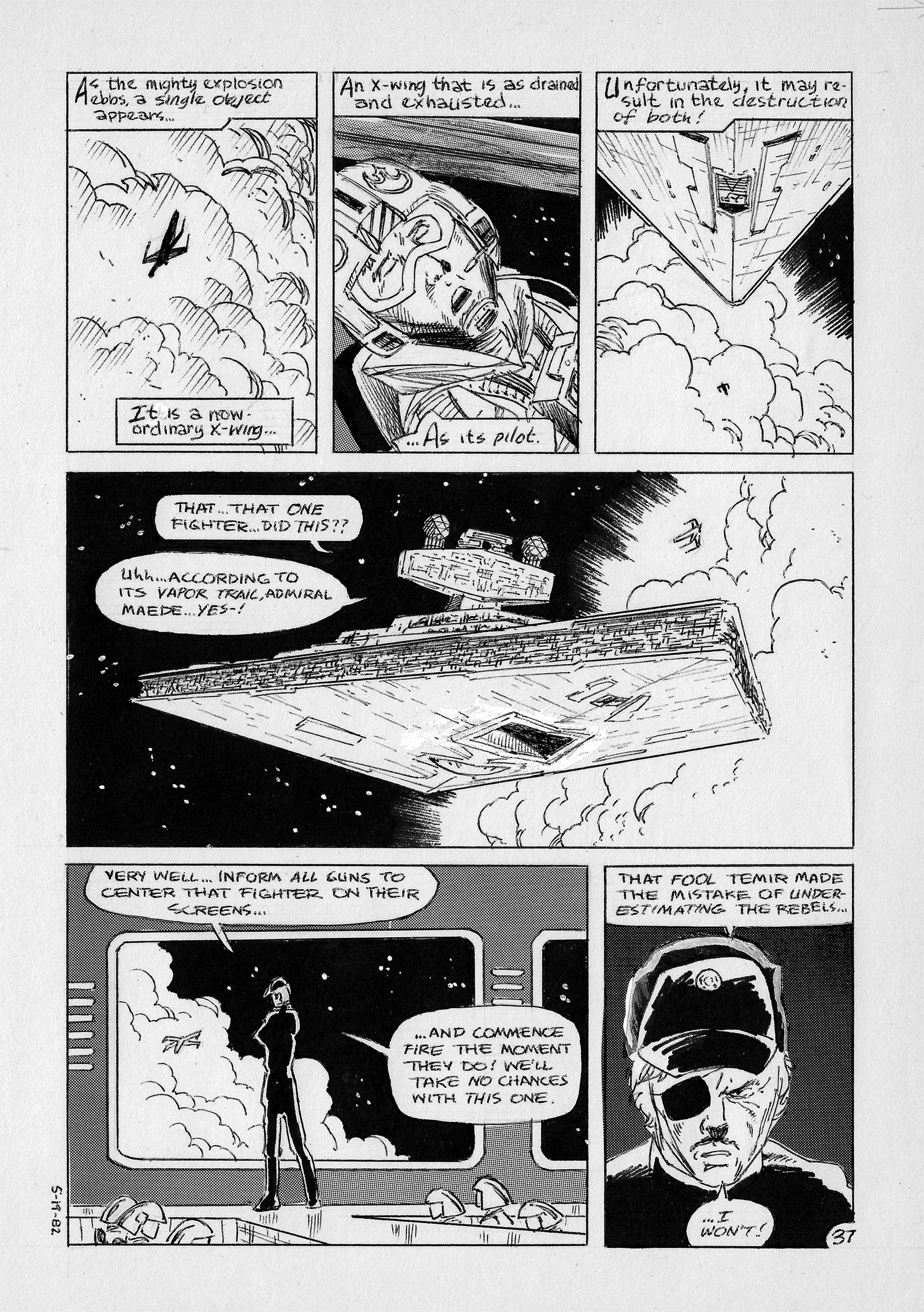

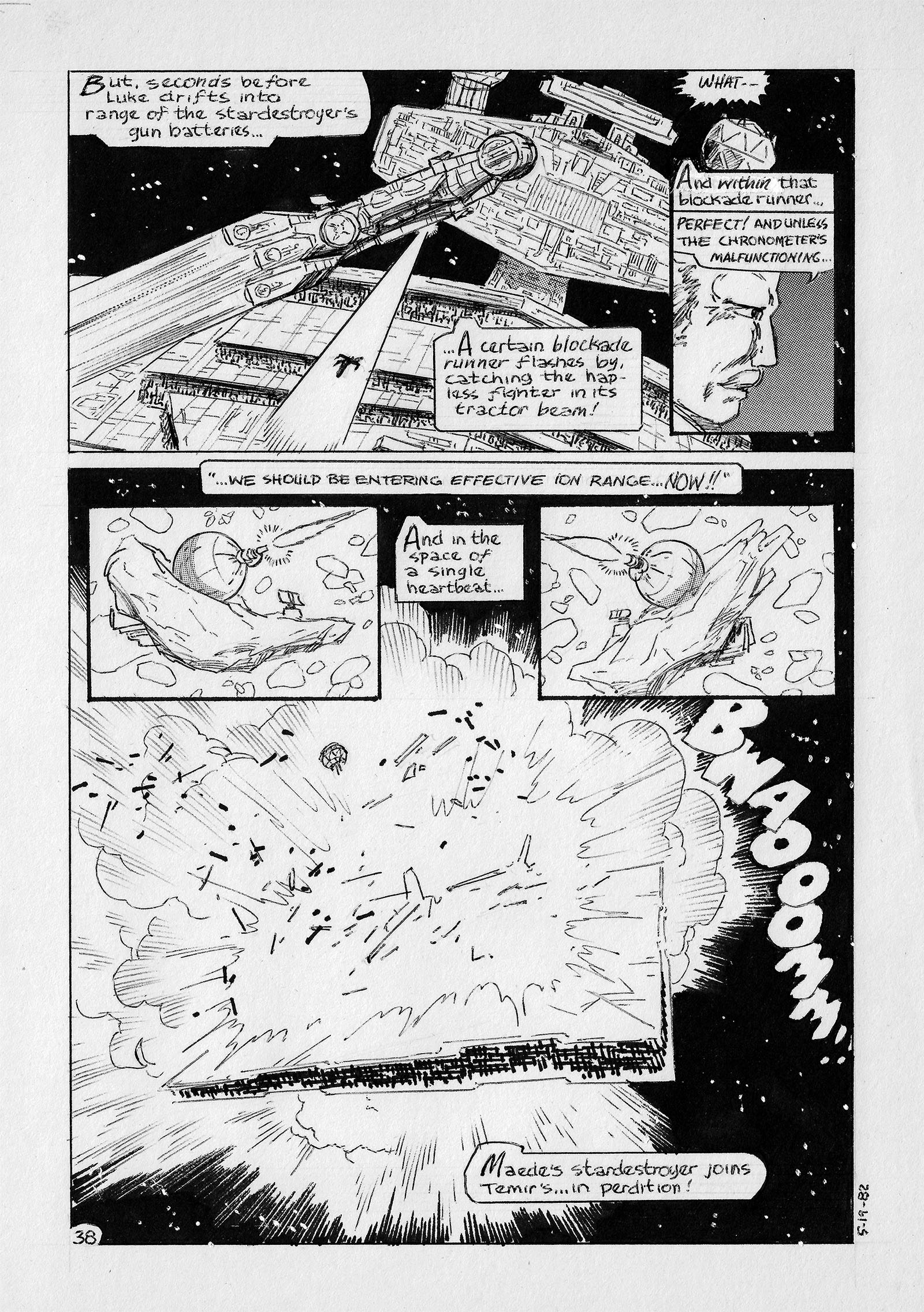

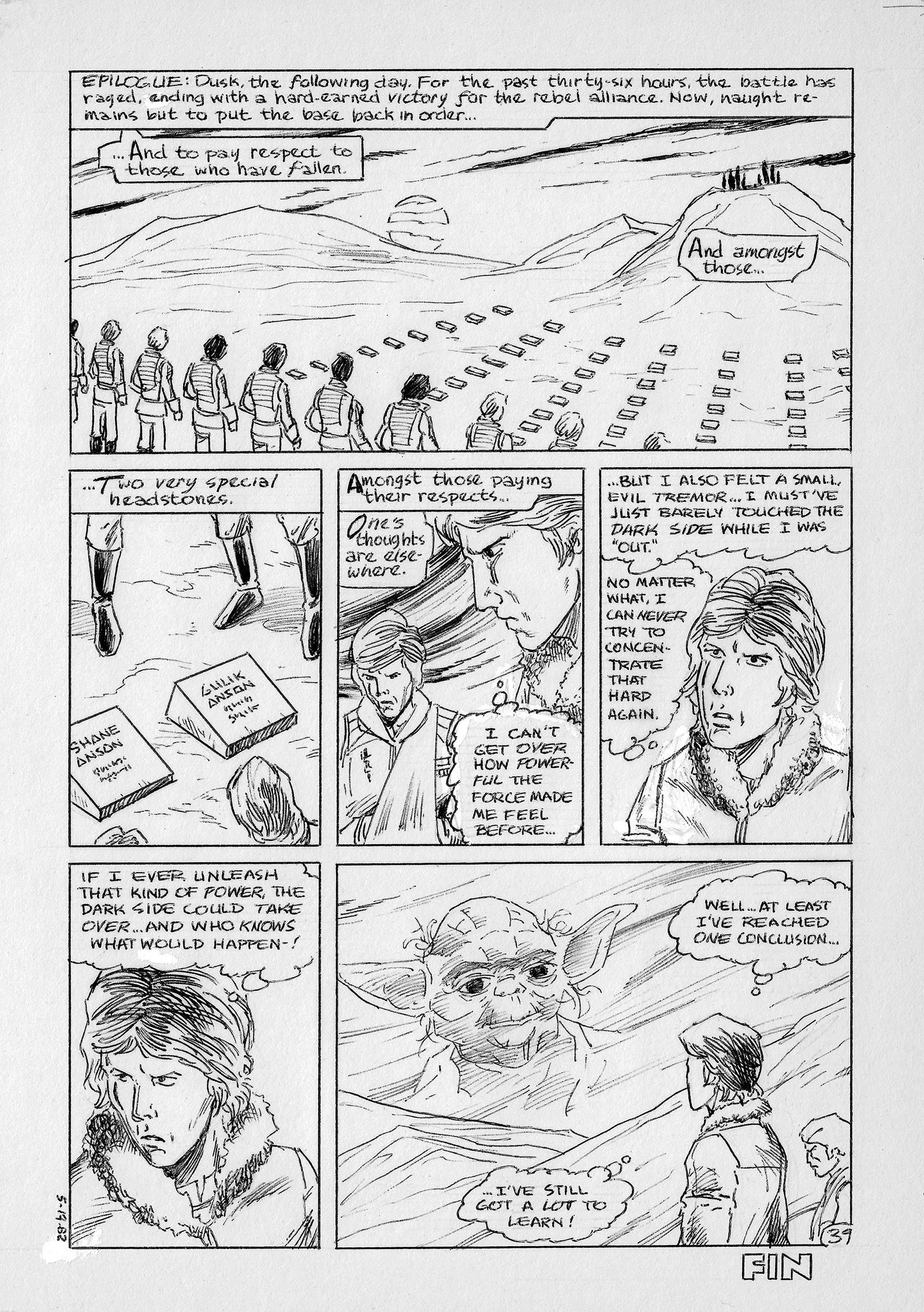

Star Wars: Deathrun, 1982

When I look back on this Star Wars comic, which I drew in May 1982, the word it evokes is “storytelling.” Not because of some artistic or narrative breakthrough, but a point in time where I finally came to intuitively understand what the word meant.

Backing up a bit, it had been about a year and a half since I got my first professional training in making comics. That was thanks to an actual published artist named Mike Gustovich who taught classes at a local arts college (which was like meeting a god when I was 15). Right from the start, he used the term “storytelling” a lot. I hadn’t heard it before in the context of comic books. I hadn’t realized that I’d seen it in action all along, and in fact had been studying it closely. I just didn’t have a word for it.

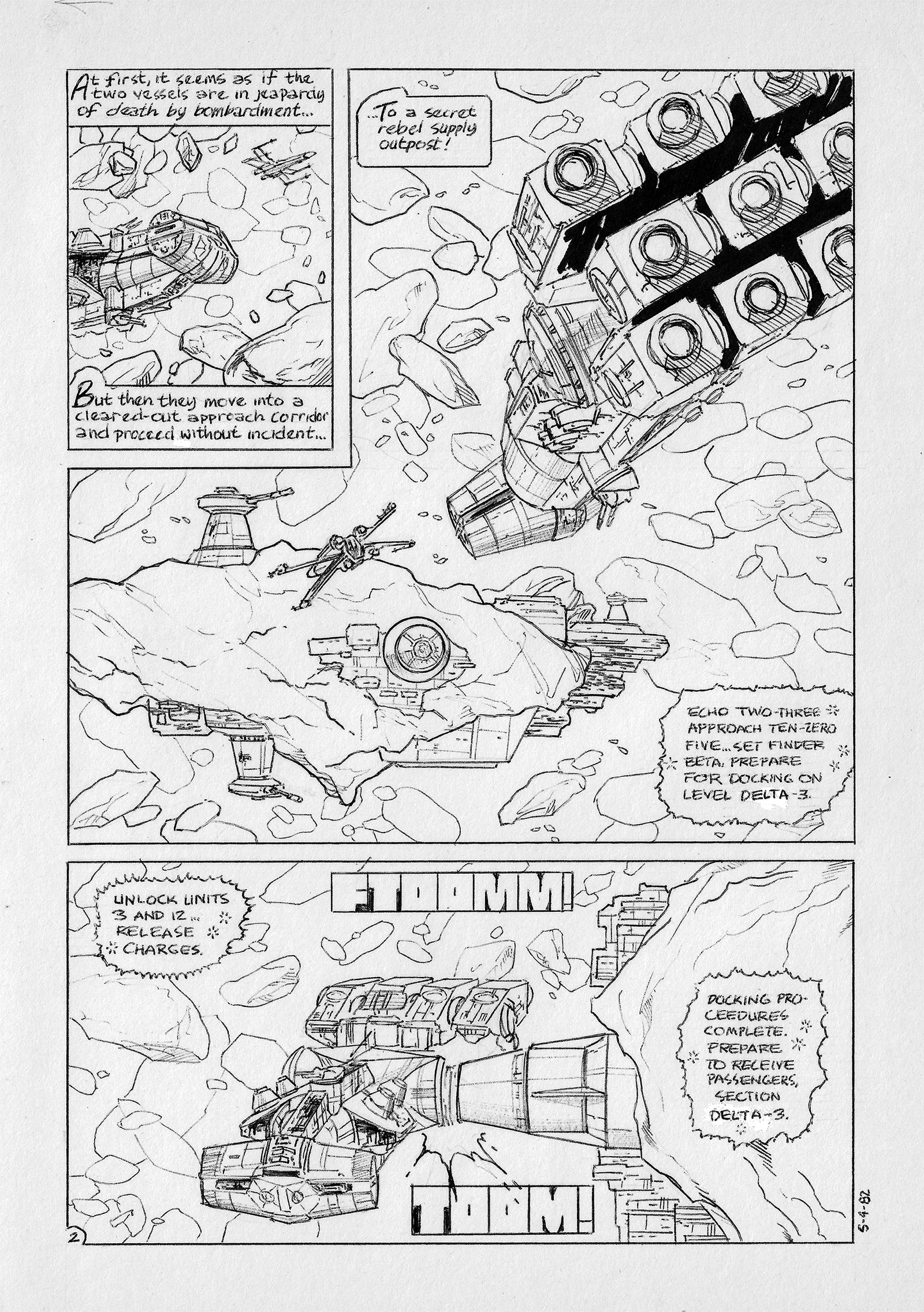

The broadest definition I can think of is this: the choosing of sequential moments to express an intentional narrative. Each word of that sentence carries a ton of weight and could fill its own book, so I’ll just settle on one: sequential.

Comics are sequential art. A series of pictures that expresses an intentional narrative. Comic book storytelling is the craft of deciding which pictures perform that function most effectively. The ability to make those decisions is more important than any other aspect of making comics. More important than writing, and even more important than drawing. If you choose exactly the right pictures, you don’t need to write a single word or even be able to draw well. You can still perfectly express an intentional narrative. Of course, it’s nice to have those other skills, but storytelling is the glue that holds them together.

The reason this story in particular evokes that word for me is because it gave me a vehicle to explore storytelling methods I hadn’t tried yet, and it brought me external validation from an unexpected source.

As you can imagine, consuming Star Wars comics was a priority for me around this time. The daily newspaper strips and the Marvel comics were essential reading. One of the writers who took on Star Wars at Marvel was a guy named David Michelinie. In one issue he dropped an idea that caught my attention for some reason (can’t remember what it was now, maybe just a made-up planet name) and I wanted to use it in a fanzine comic. I wrote him a letter (care of Marvel) to explain this and asked for permission. In retrospect, I can see that this was completely unnecessary, but it seemed like the courteous thing to do.

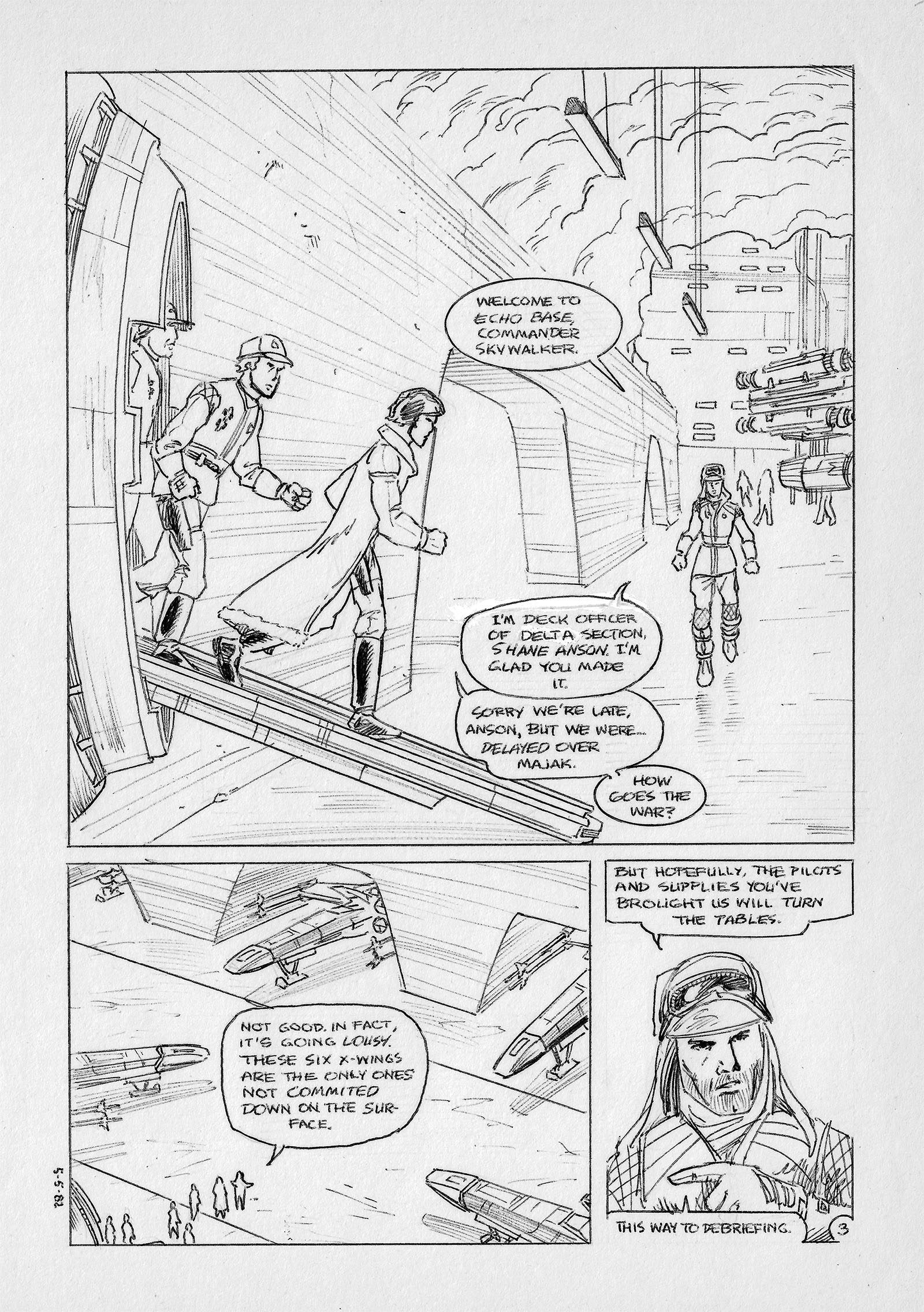

A short time later (less than a month), he wrote me back and said it was totally fine with him. And that he had “finished the Star Wars writing assignment” anyway. It sort of blew my mind that he called it an “assignment.” Like homework, or a temp job. To me, a 16-year-old kid who ate, breathed, and dreamed Star Wars 24/7, that was quite a perspective shift.

He included his address in the return letter, so as a thank-you gesture I mailed him a photocopy of the Star Wars fanzine comic I had just finished. That was this comic, Deathrun. Again, a short time later, he sent me another letter. I wish I still had it, because I’d post it right here in this spot.

David was the first professional comic writer I’d ever encountered, and he generously complimented my work. One line from that letter is etched into my memory: “You perhaps lack the polish of a seasoned pro, but you’re NOT a seasoned pro.” He suggested ways I could have made things clearer, or extra scenes that would have added information, all of which were helpful. But here’s the thing: he specifically complimented me on my storytelling.

There was that word again. Reading it in that letter locked it in for me. I had chosen sequential moments to express an intentional narrative, and a professional comic book writer approved my choices.

After honing that skill for another fourteen years, I found that it translated perfectly into an animation career. Drawing storyboards for TV cartoons used all the same creative muscles. Knowing intuitively which images to choose made me a natural, pleased my many bosses, and propelled me up the ladder faster than I expected.

Working as a storyboard artist brought me to another realization that built on top of the previous one: humans are natural puzzle solvers. It’s an evolutionary survival tool. It’s how we transform chaos into order, and we get a satisfying dopamine hit every time we succeed. Creating sequential art, whether for a comic book or a storyboard, is a form of puzzle solving. The end product is an intentional narrative. And here’s thing: what you show is just as important as what you leave out. Leaving things out turns your audience into a collaborator; give them a chance to find some puzzle pieces on their own, and they’ll be fully engaged in helping you to complete it. There’s plenty of dopamine to go around.

Each and every comic or storyboard I ever drew was a step forward in learning how to choose the best sequential moments. That will continue until the day I stop.

All that said, you’ll easily recognize the storytelling experiment I attempted in this story. It forced me to think about how time is compressed and expanded on a page, and how to work with the “rule of threes.” (Also known as thesis/antithesis/synthesis.) As you can imagine, it was quite empowering to get professional approval afterward.

Deathrun was published in issue 1 of a fanzine titled Legends of Light (Pooz Press, August 1982).

Side note: Luke drops the name “Majak” in the first panel. That refers to another story I was planning, but never actually started, called The Moons of Majak. In it, Luke and these pilots were on their way to this base and stopped for supplies on the planet Majak, which was surrounded by moons. The empire tracked them there and started bombarding the surface. The natives were unconcerned, saying their gods would protect them. No amount of reality-checking from the rebels would dissuade them. Finally, those “gods” were revealed in the form of the moons, which began to crush the invading Star Destroyers. In other words, the “moons” were living creatures. I can still see the climactic image in my head. It’s a shame I never got around to drawing it.