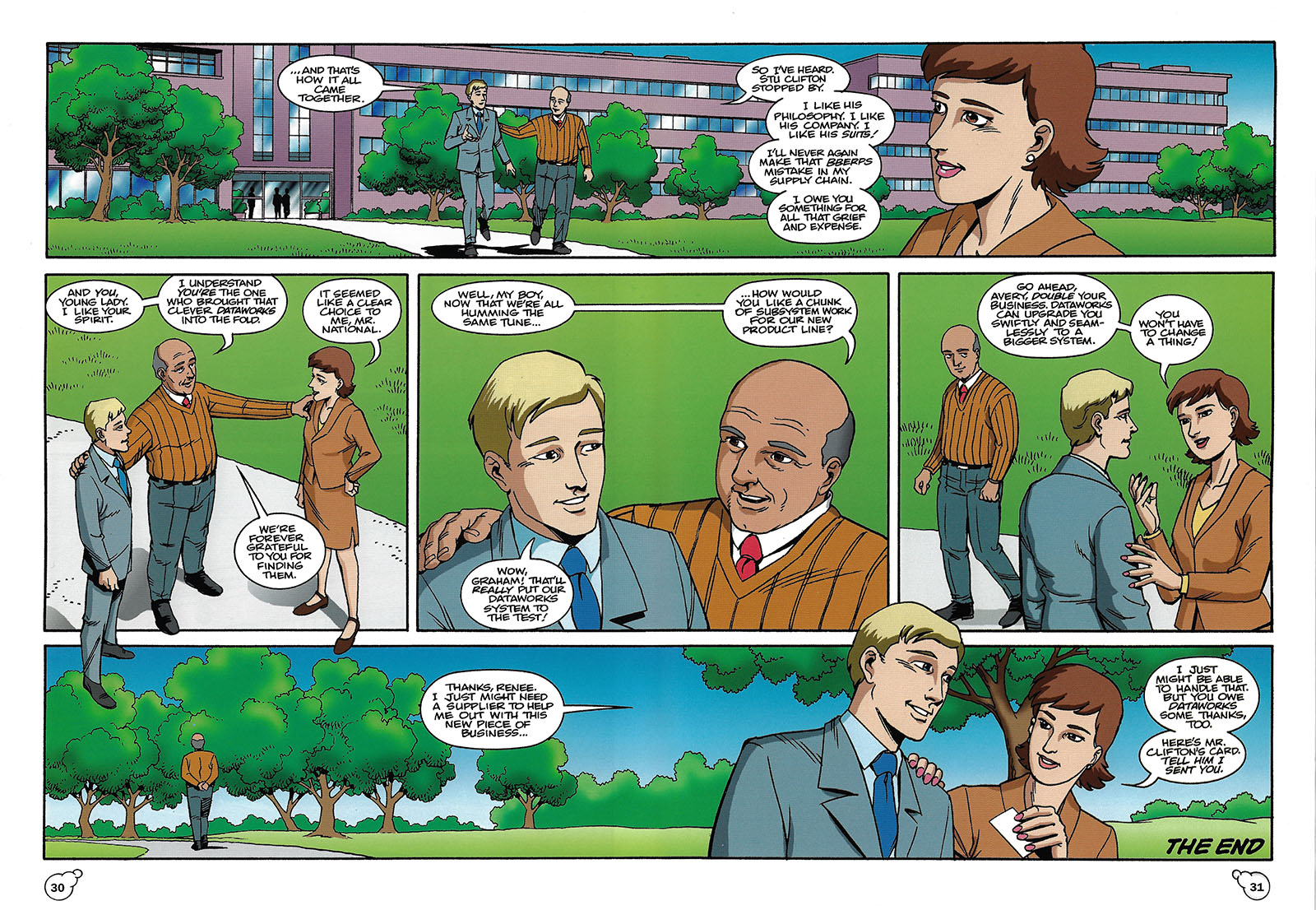

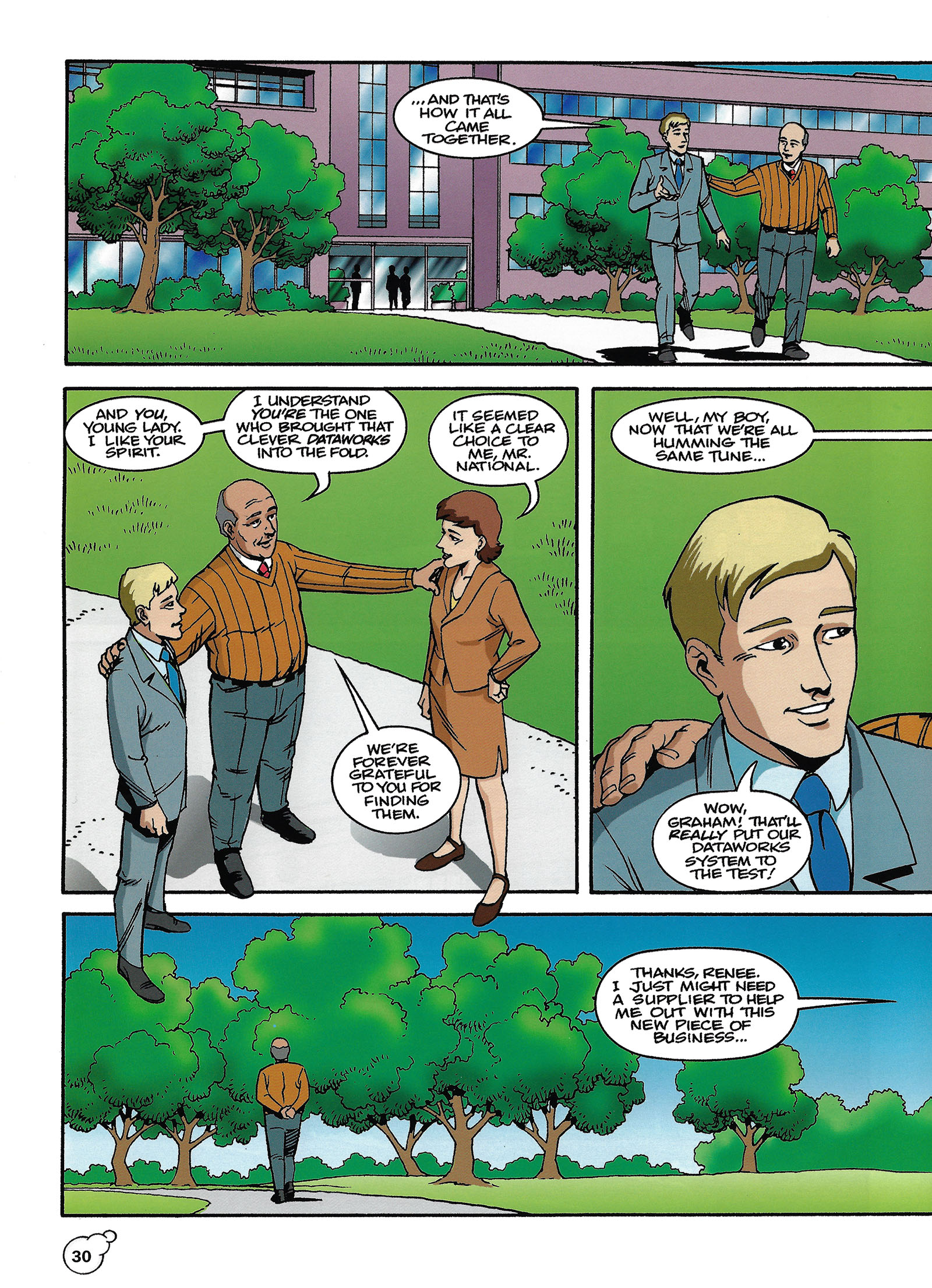

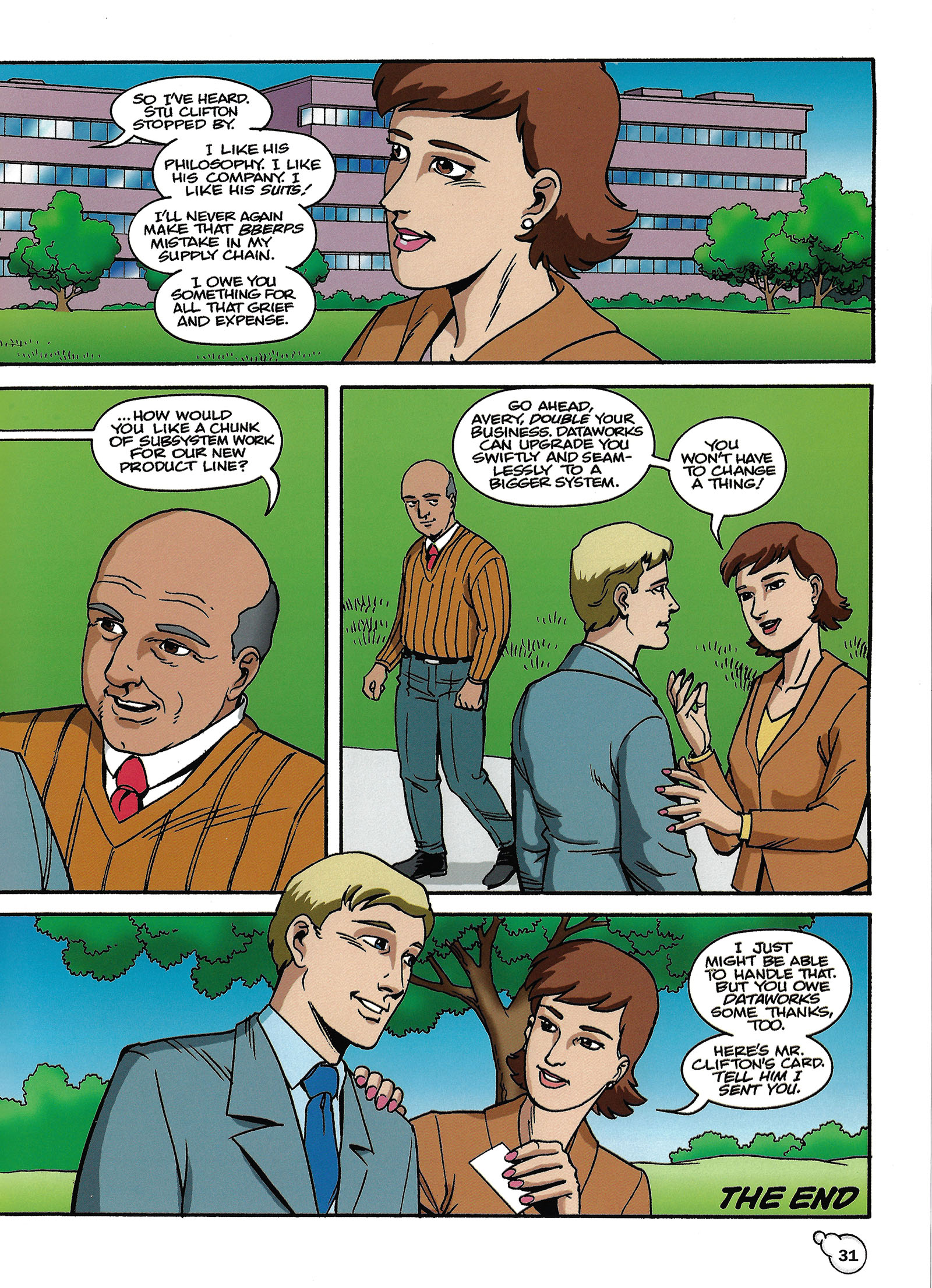

Secret Comics: Dataworks 1997 Annual Report

I’ve said it before in these pages, but it bears repeating: if you really want to draw comics, don’t be picky about where your opportunities come from. When left to our own devices, we draw what we love, whether it’s spaceships or horses or monsters. Which is just fine. But there’s a limit to what you can learn from what’s already inside your own head. And the potential for comics as a learning tool is practically limitless.

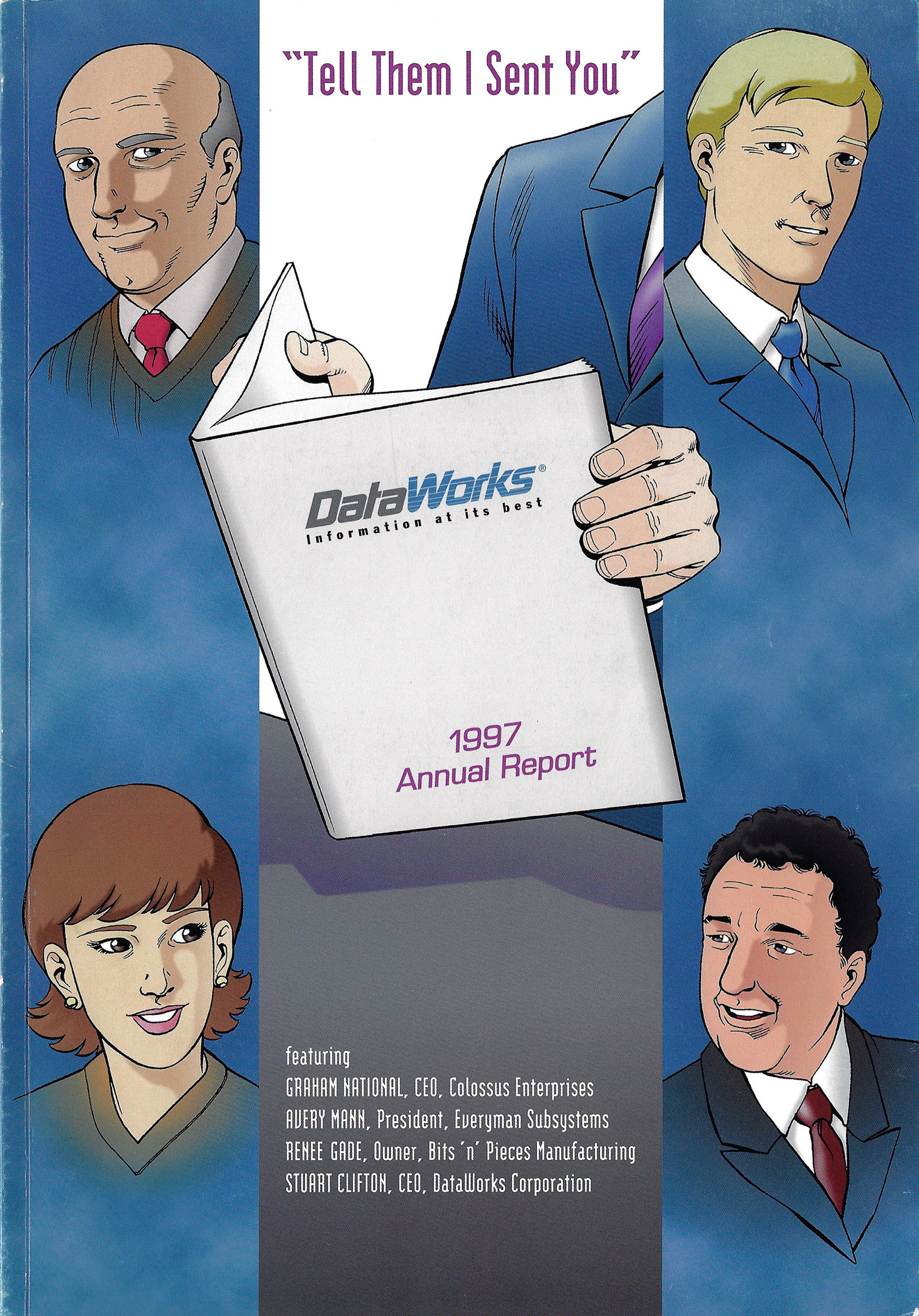

In 1997, I was getting comfortable in my new TV animation career (directing episodes of Extreme Ghostbusters for Sony) but still drawing comics on the side. I’d refined my process to be as fast as possible, which was a good thing since I couldn’t draw comics full time any more. I’d eliminated the inking process entirely, drawing in pencil and strengthening the line work in Photoshop before adding color and effects.

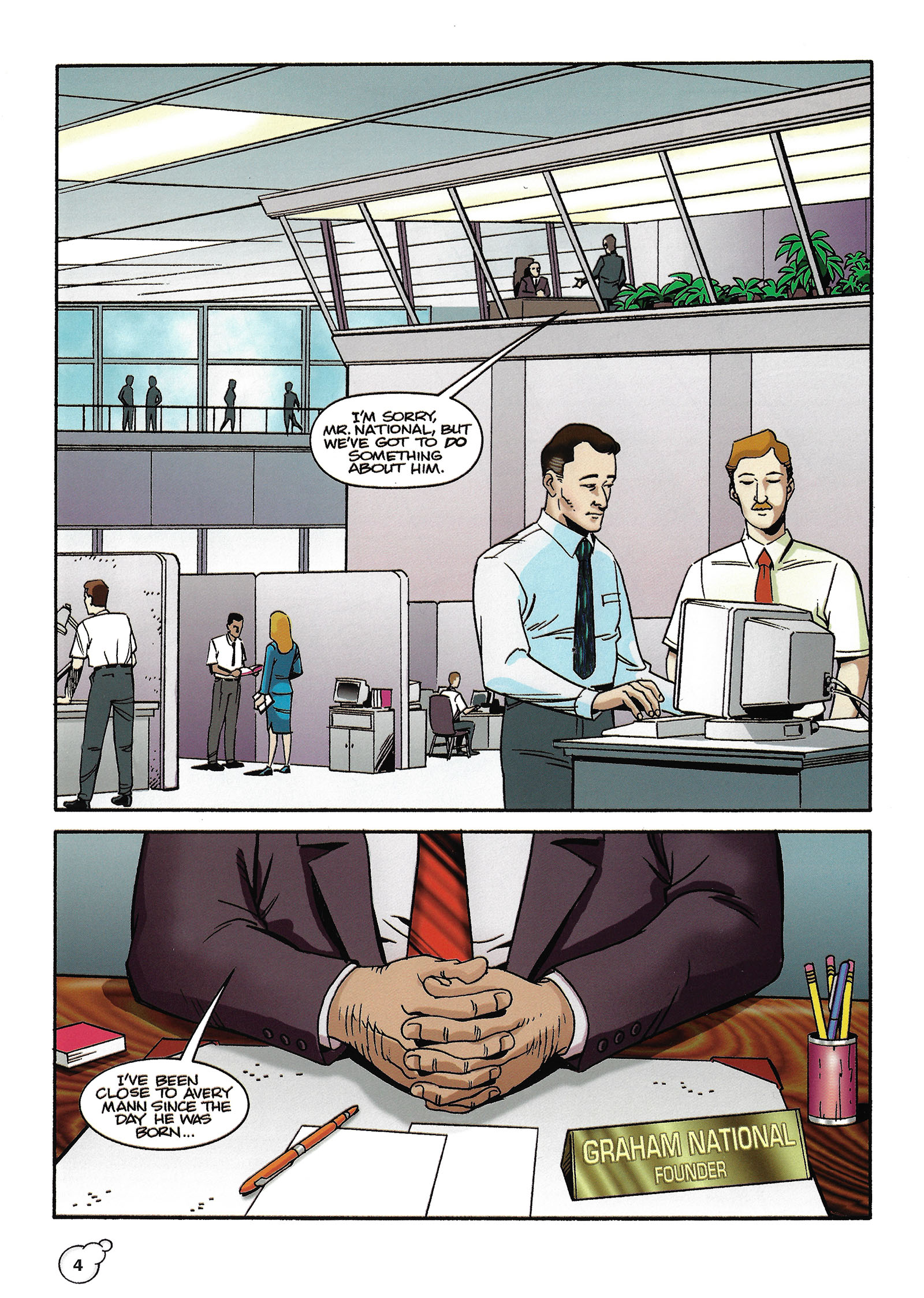

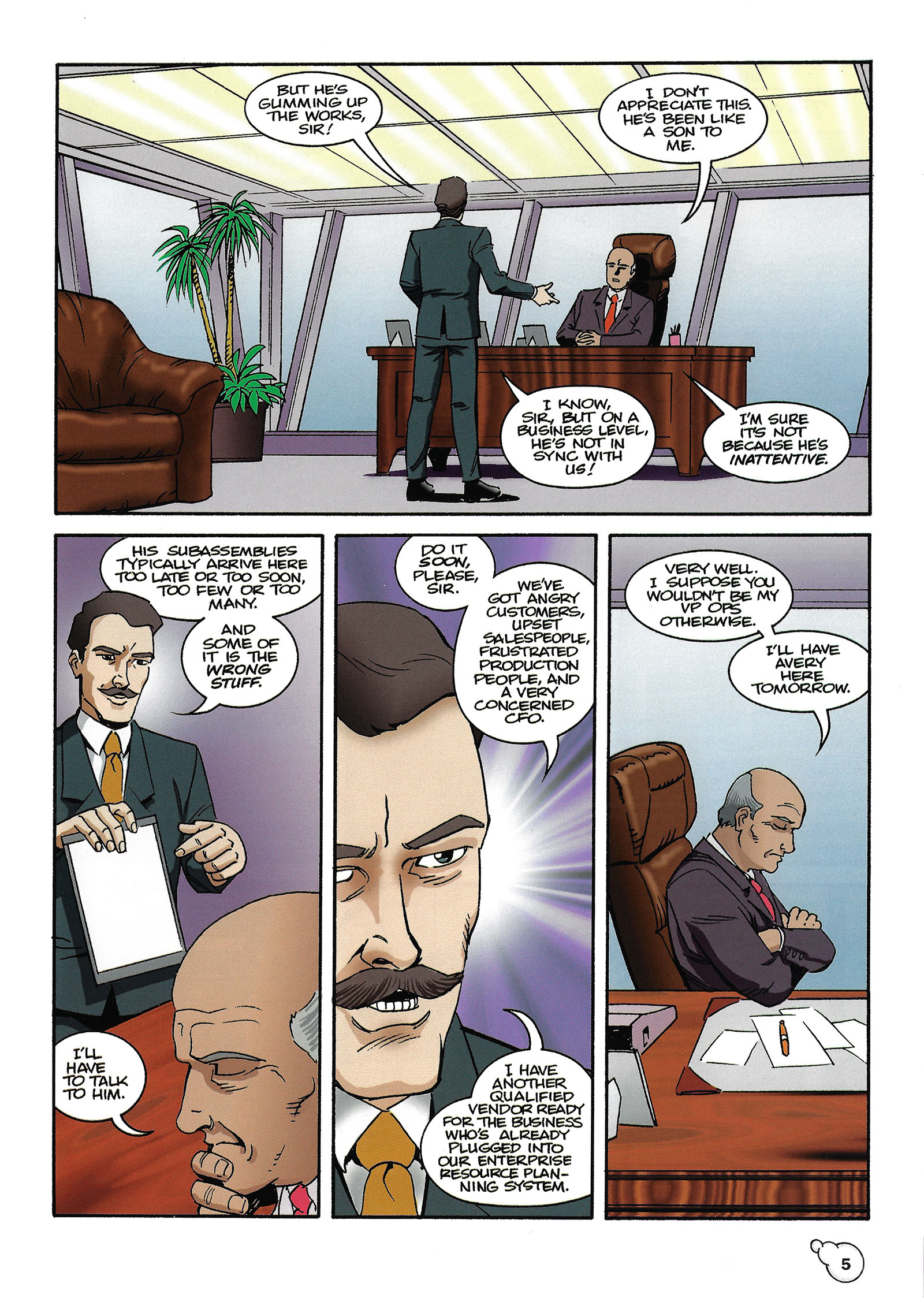

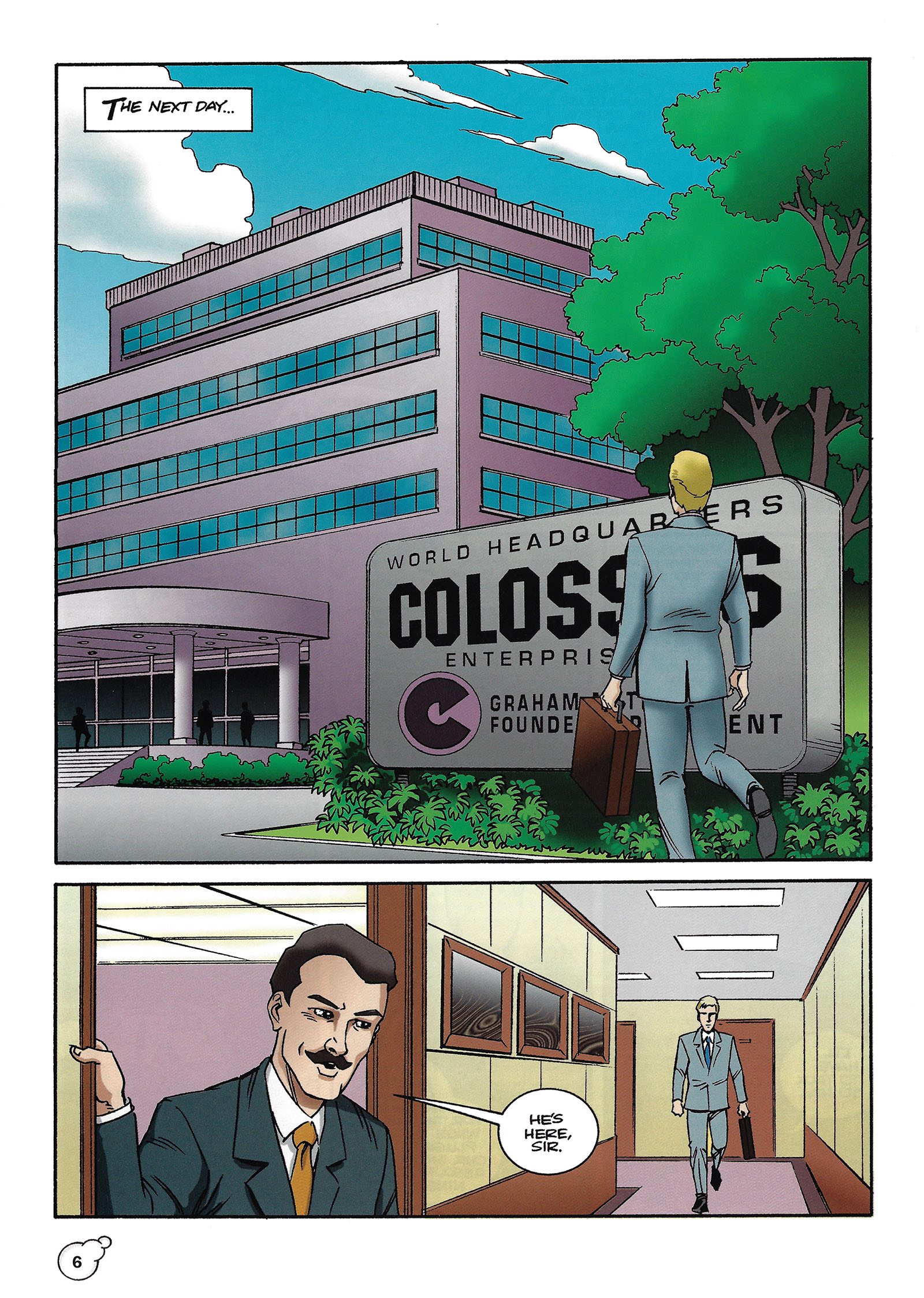

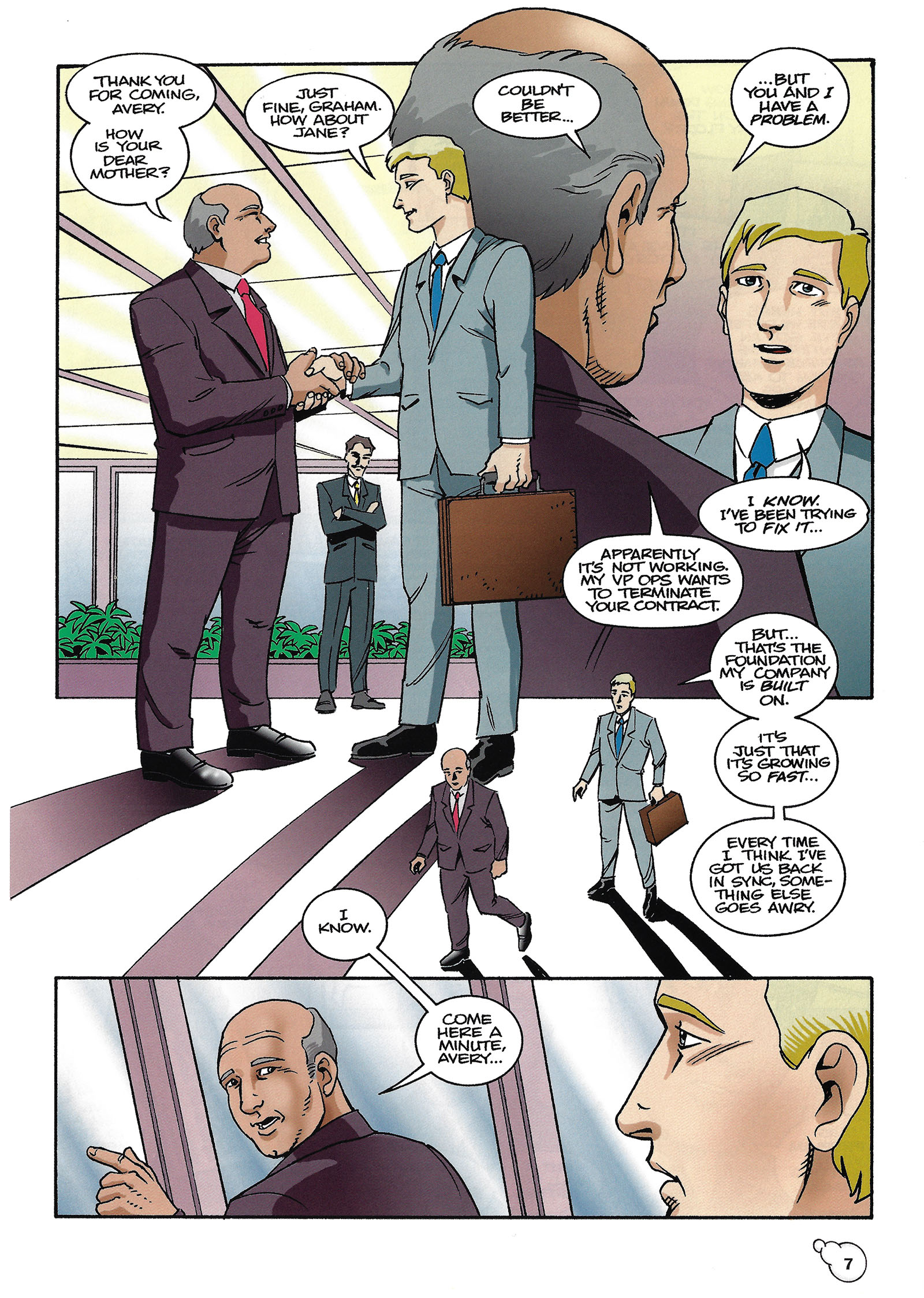

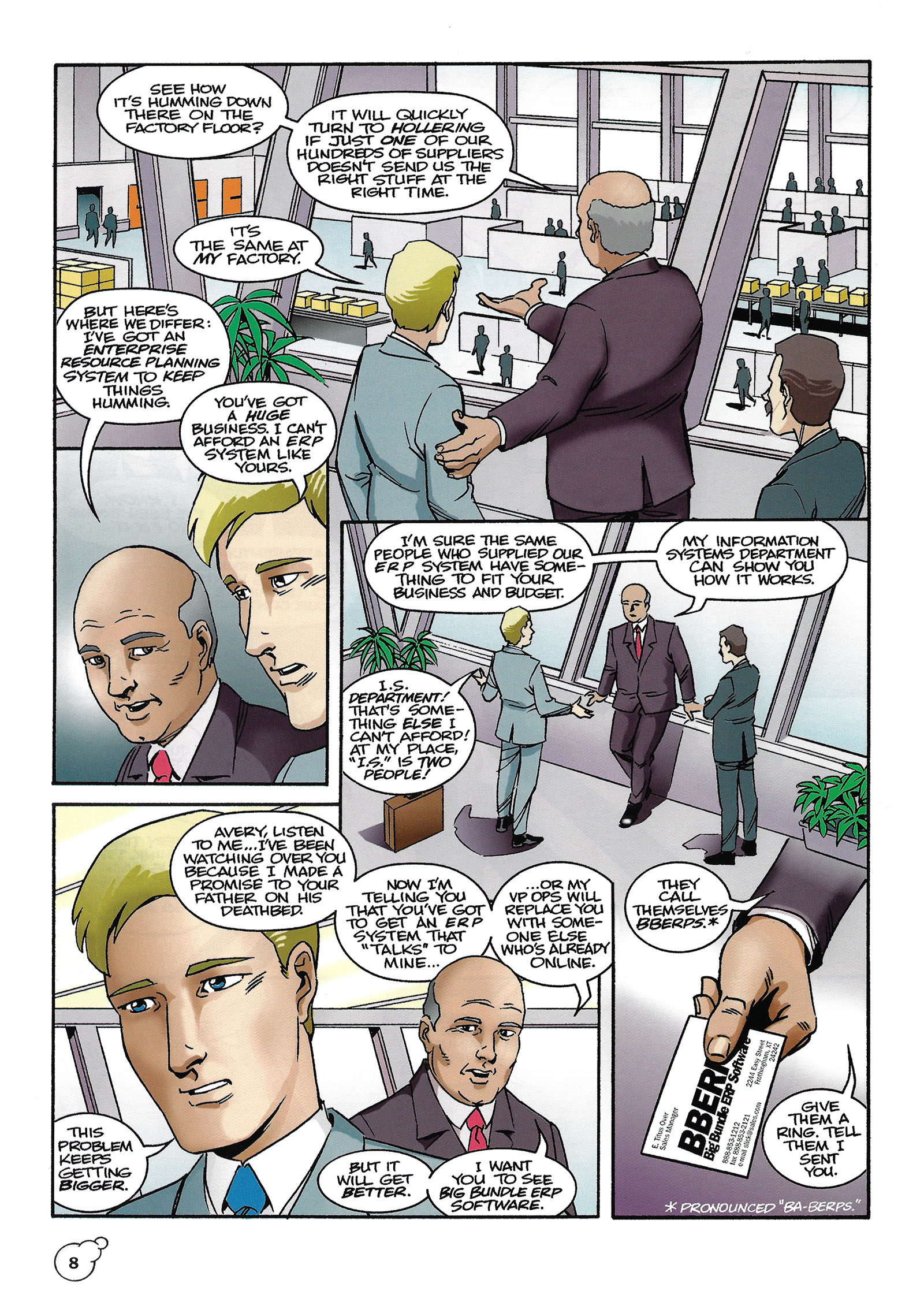

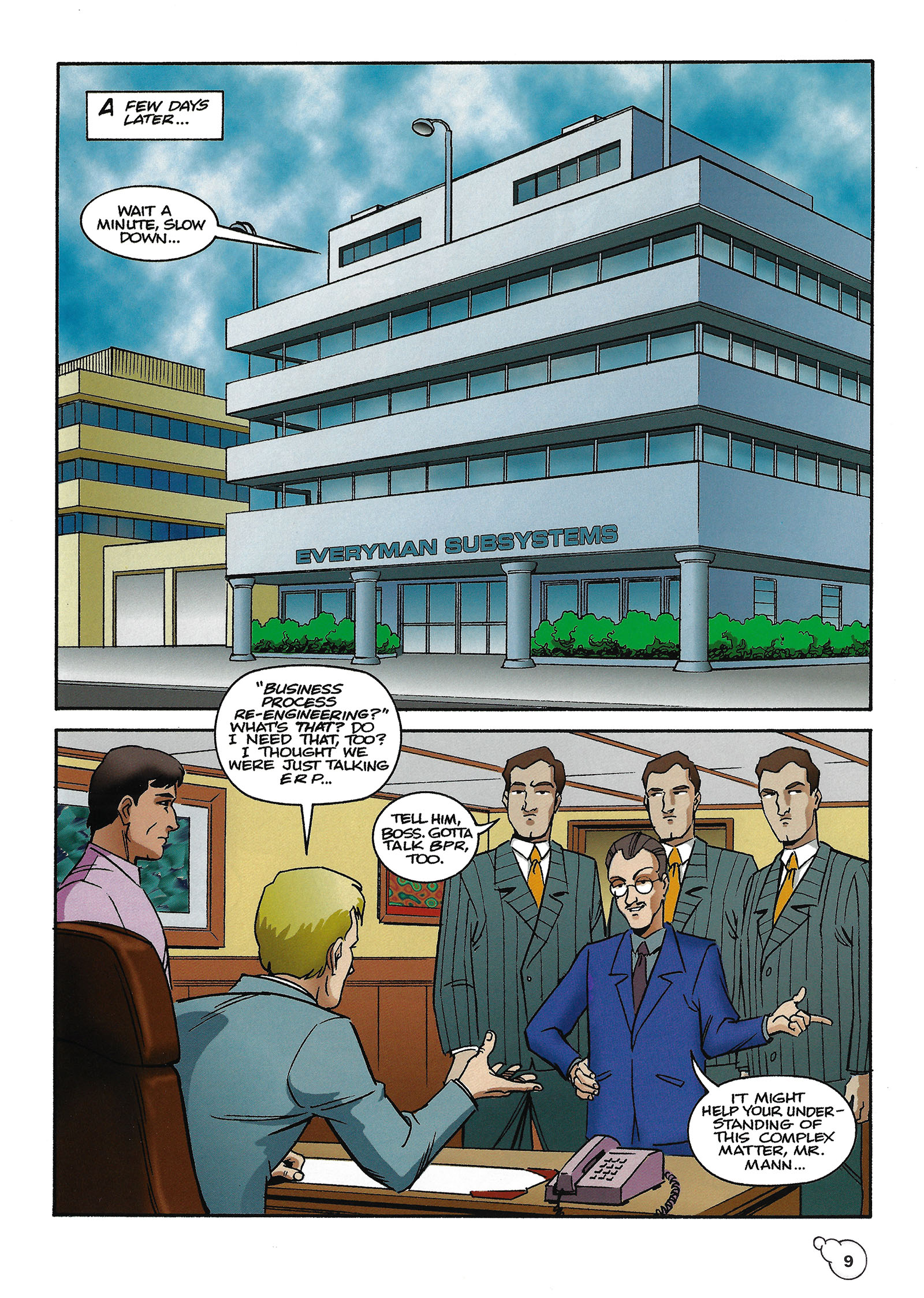

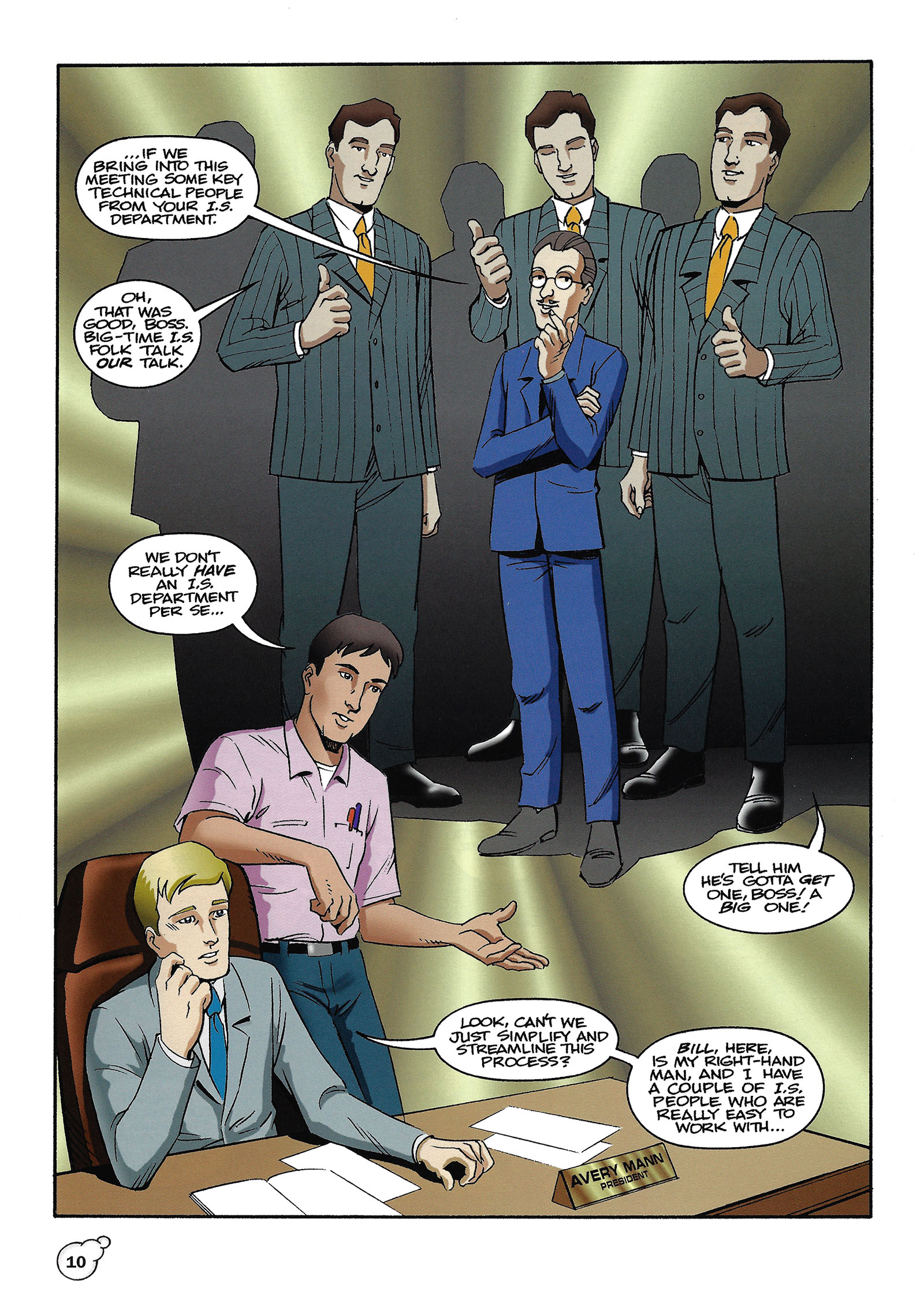

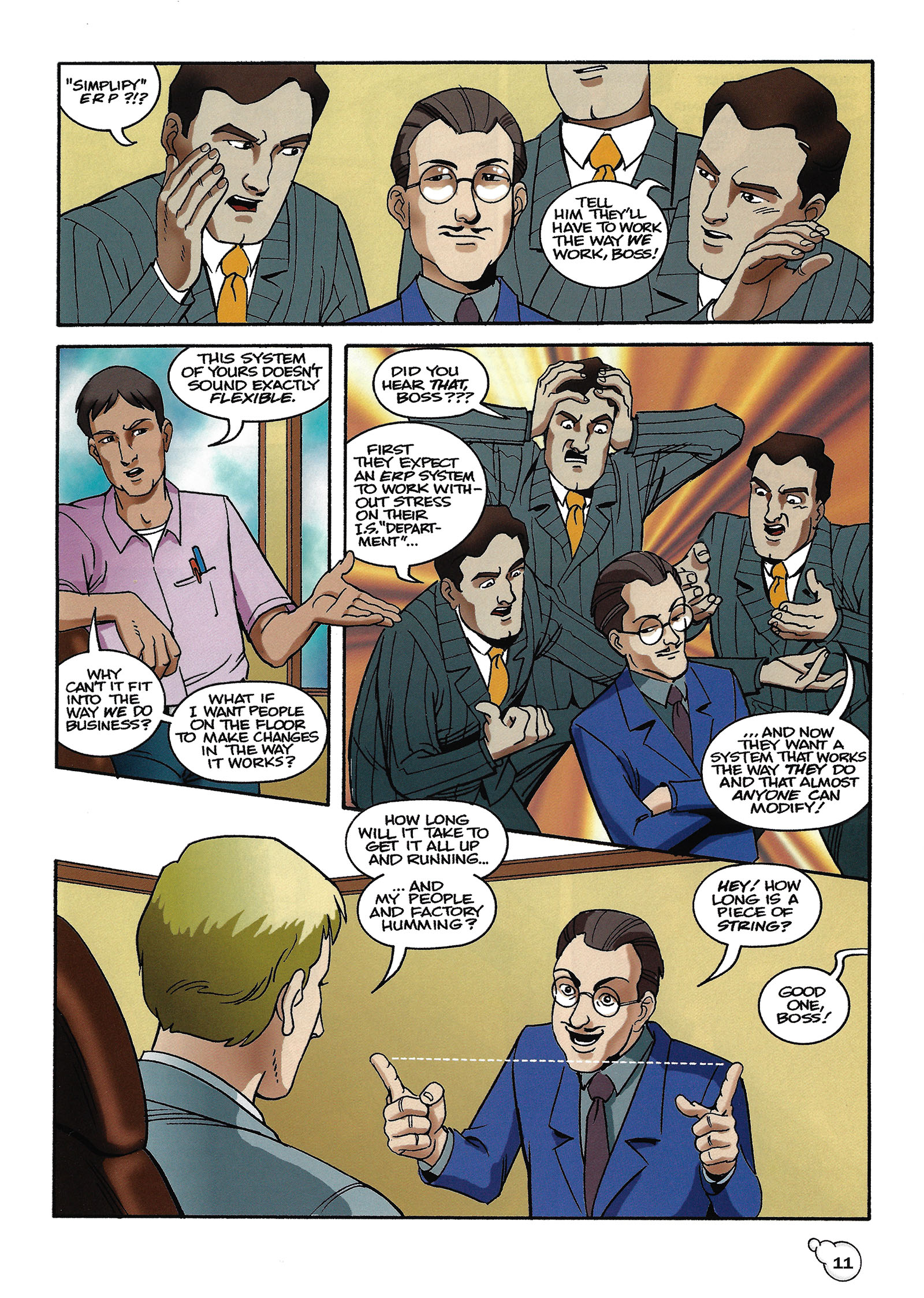

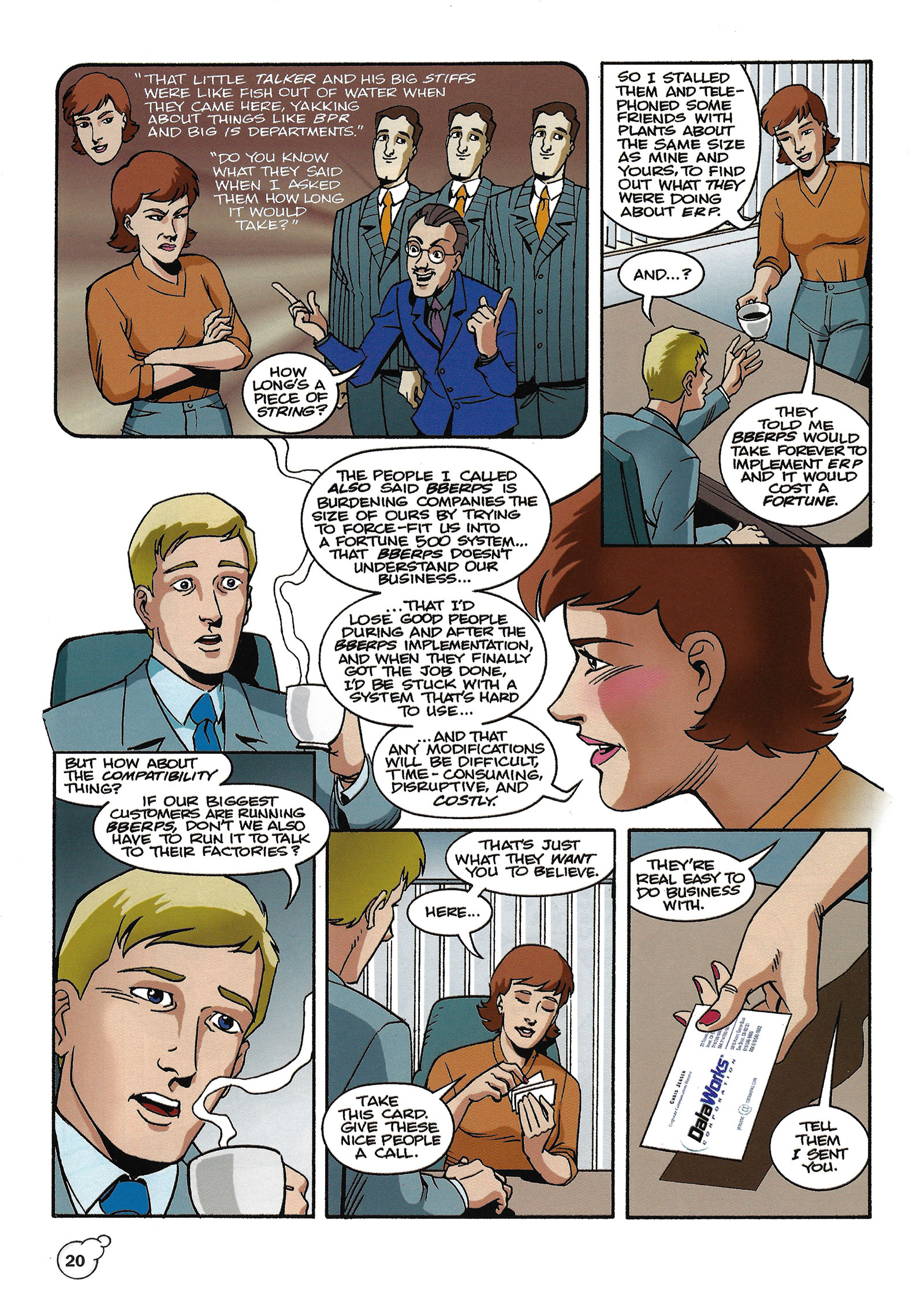

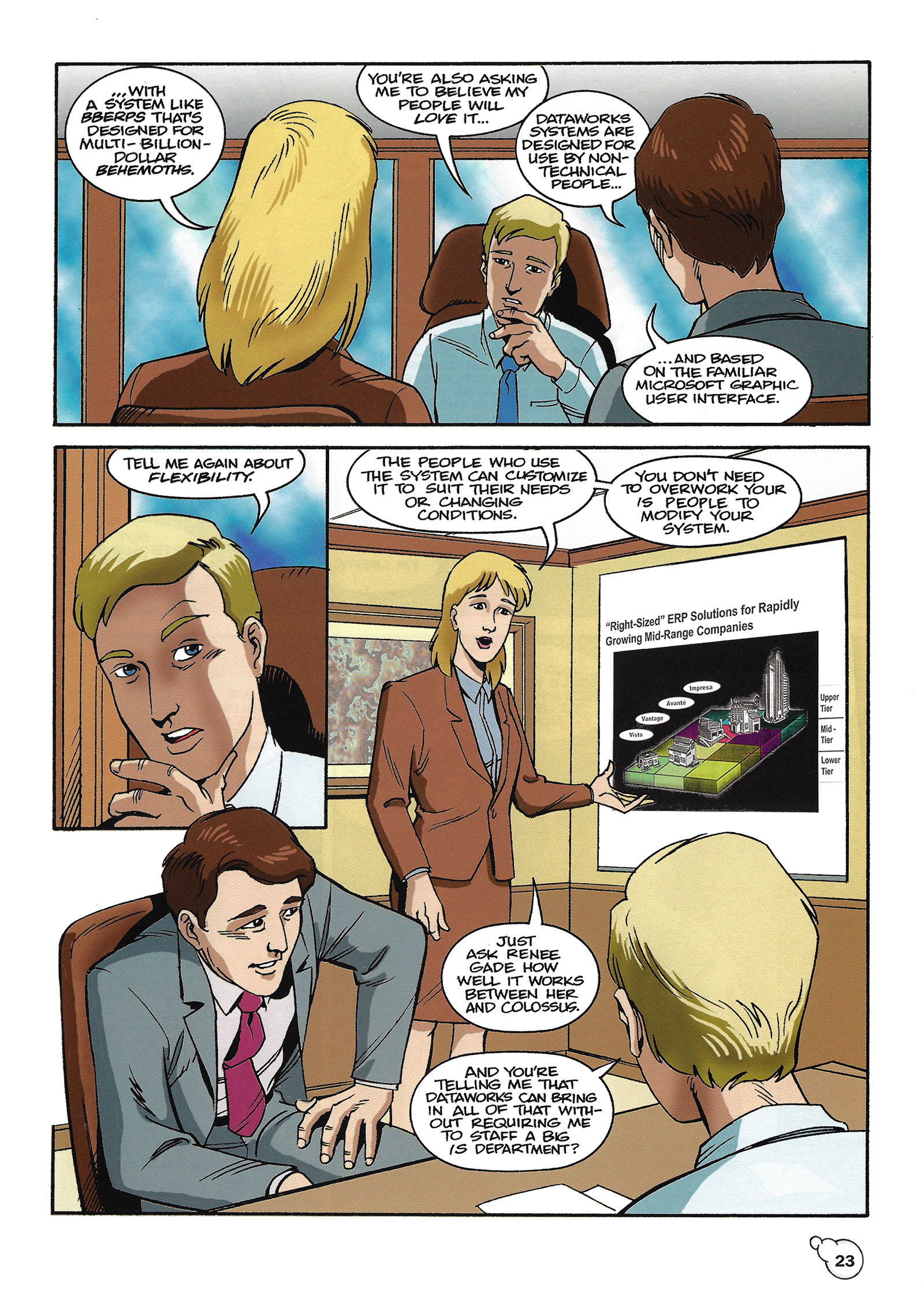

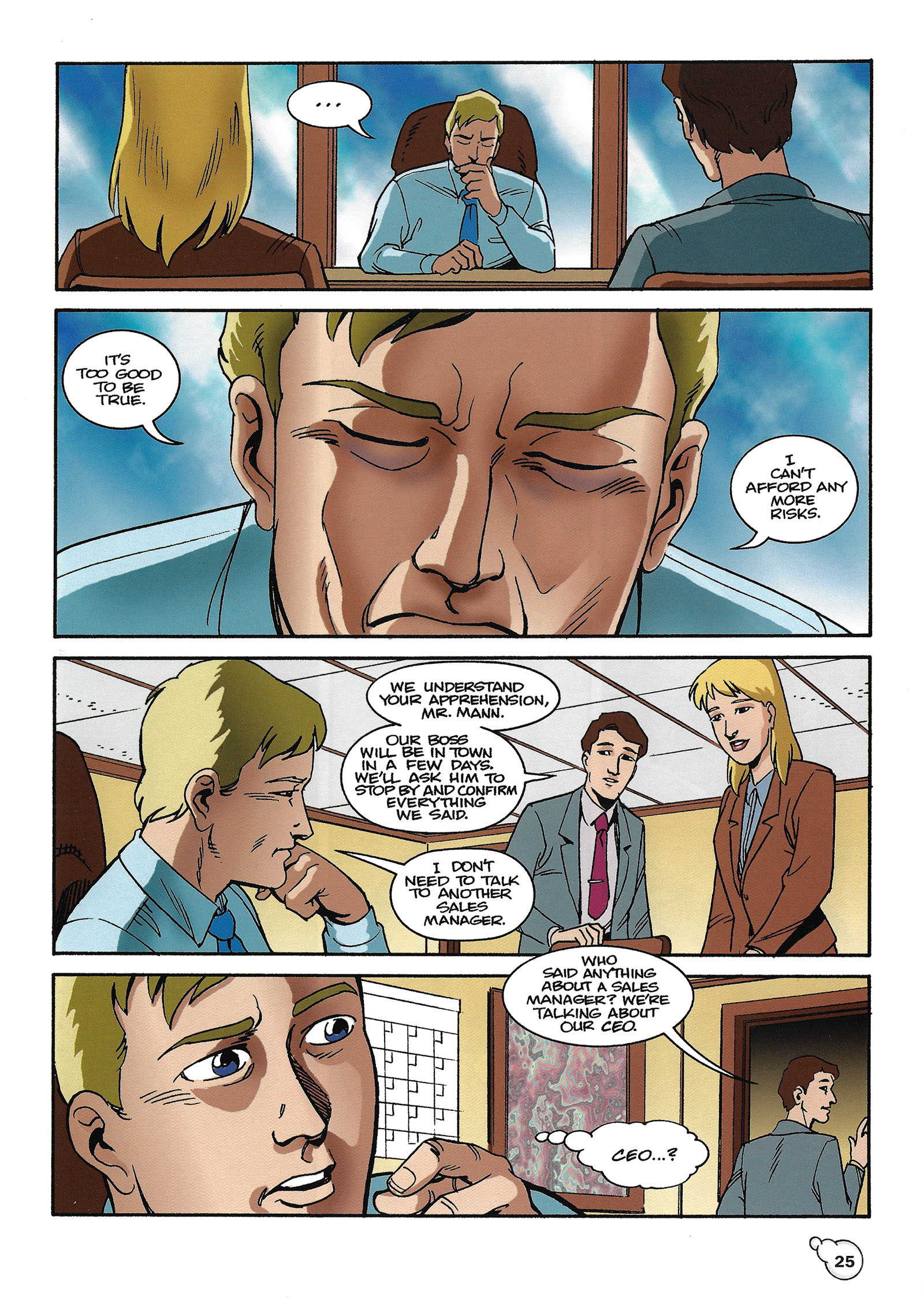

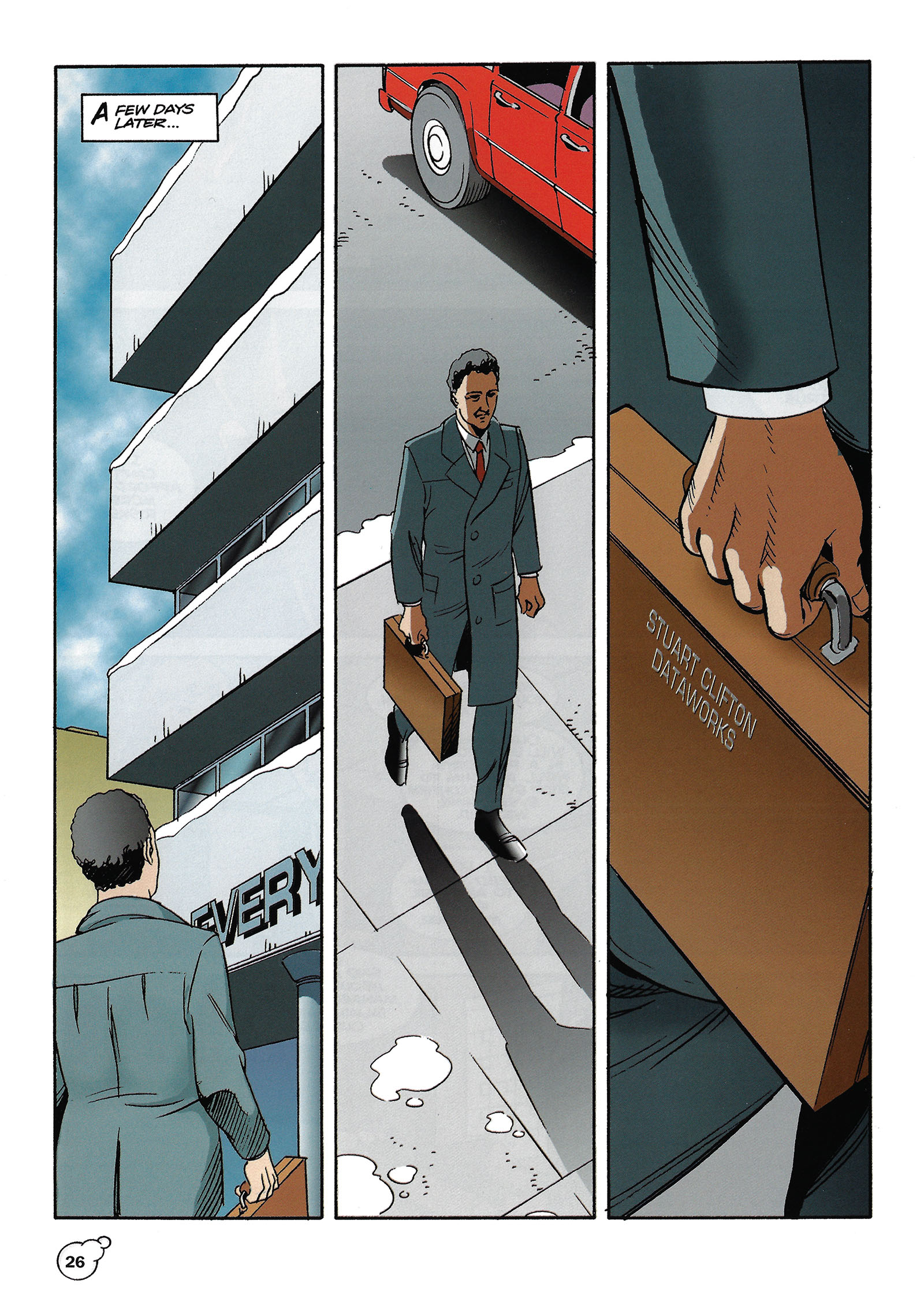

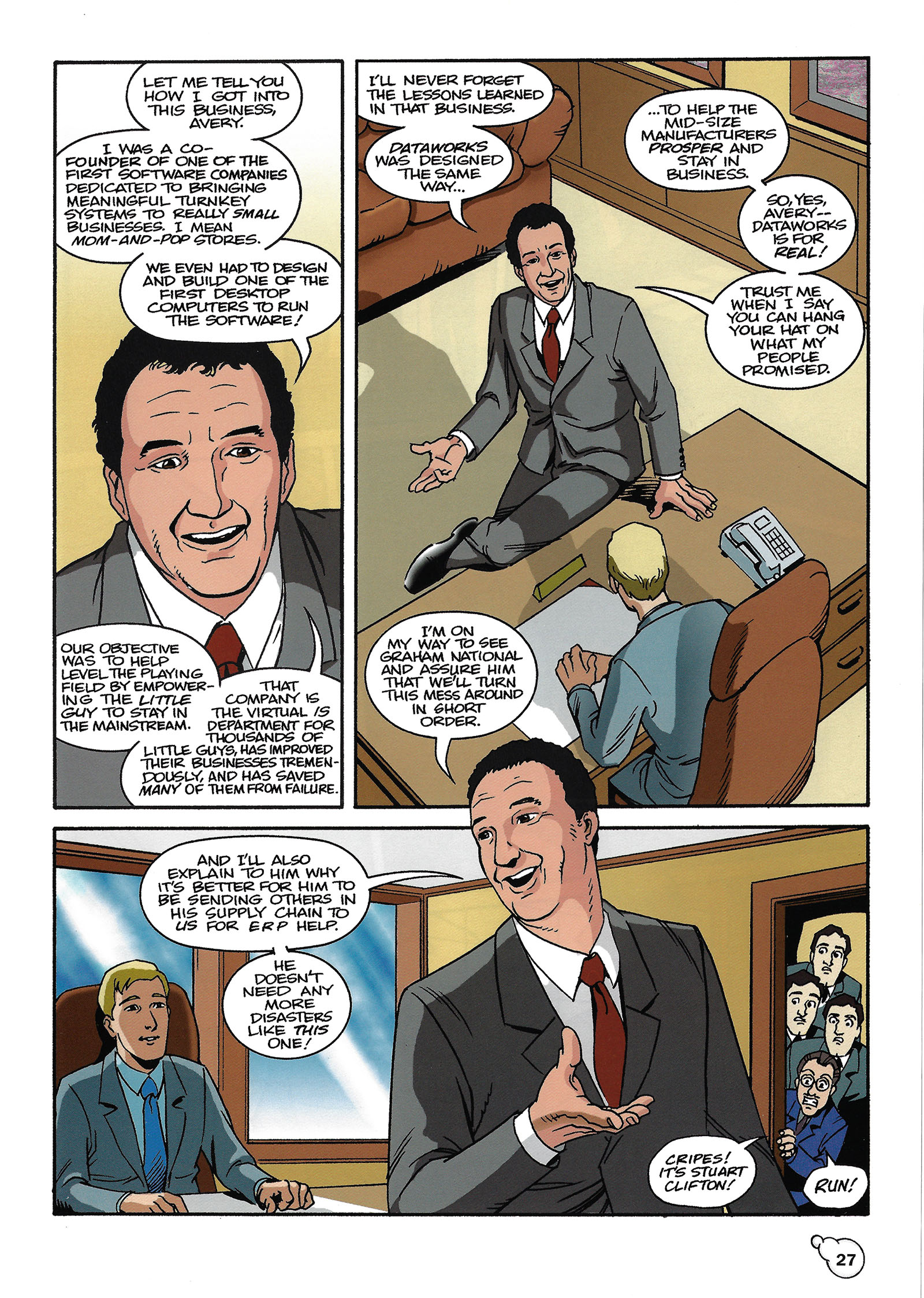

I got a call out of the blue one day from a guy who ran his own commercial art studio. I really wish I could remember his name, but I can’t. So I’ll call him Pete. Pete was looking for a comic book artist to help him with a wild idea he’d pitched to a company called Dataworks. Their jam was data management for product and asset trafficking, called ERPS in the business world (Enterprise Resource Planning Systems). One of Pete’s jams was designing annual reports for corporations, which are about as dry as a Martian desert. He thought there must be a way to make one more interesting.

He knew about comic books already, but I think he’d only recently learned about manga – specifically how it was used everywhere in Japan, even in the business world. So he thought, “why not turn the next Dataworks annual report into a manga?”

He got in touch with Toren Smith, who at the time was heavily involved in importing manga to America, and asked for some advice on how to proceed. Toren knew me, so he gave Pete my number. When Pete proposed the idea to me, the name Will Eisner instantly flashed into my head.

Along with Jack Kirby, Will Eisner was the godfather of the American comic book. But where Jack pretty much stuck to drama and fantasy, Will took comics in every possible direction, even US Army training manuals during WWII (see one here). Plus, he’s credited with originating the term “graphic novel.” Will would have accepted a corporate job without hesitation. So I had no business turning it down.

It was interesting to me that Pete came to this concept through “manga” rather than “comics.” For all intents and purposes, they are the same thing. They just use different visual vocabularies. I don’t think he quite understood that distinction. He was just fascinated by the idea that “manga” could be a new, unique approach to communicating a company’s message and I had no desire to contradict him.

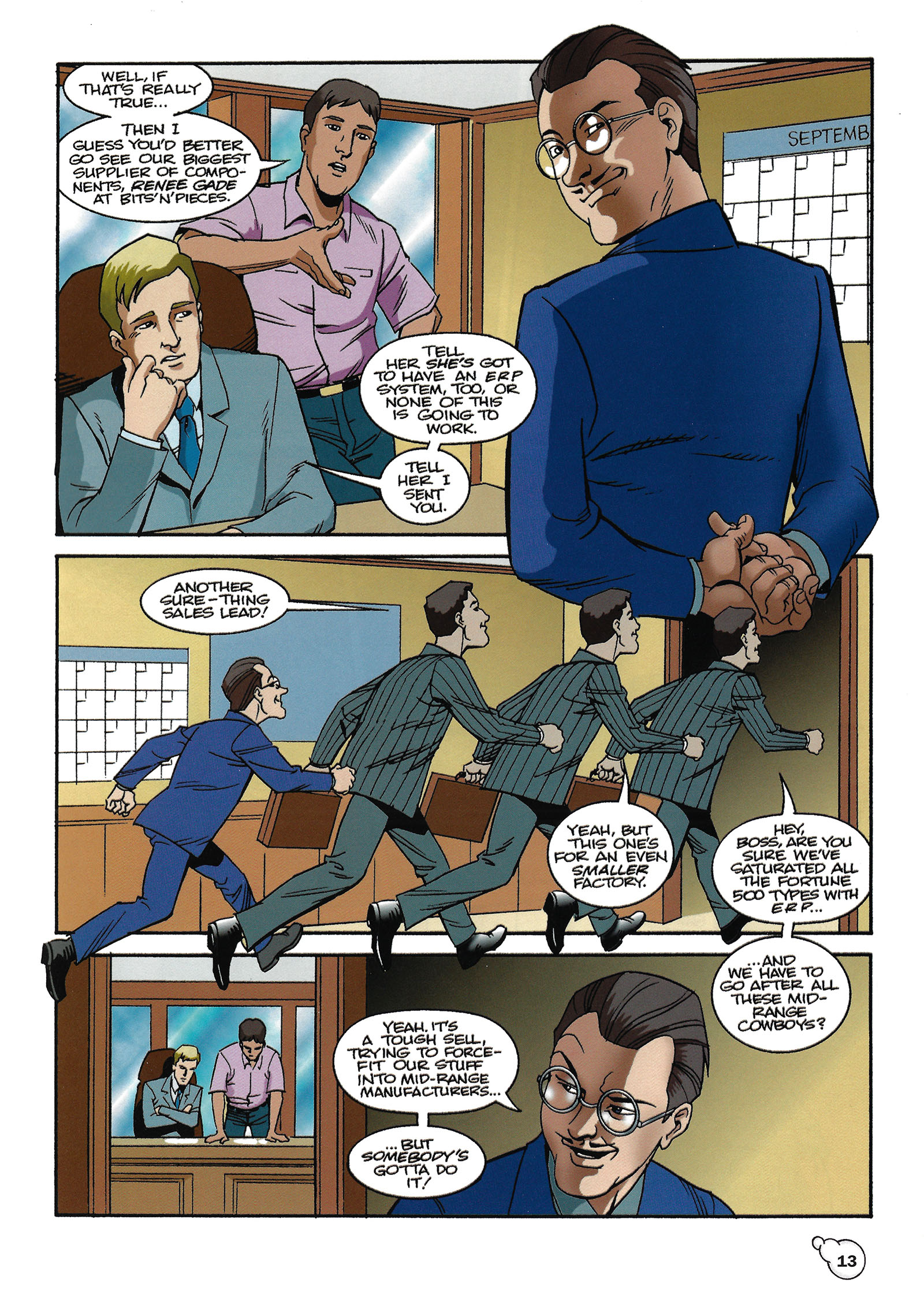

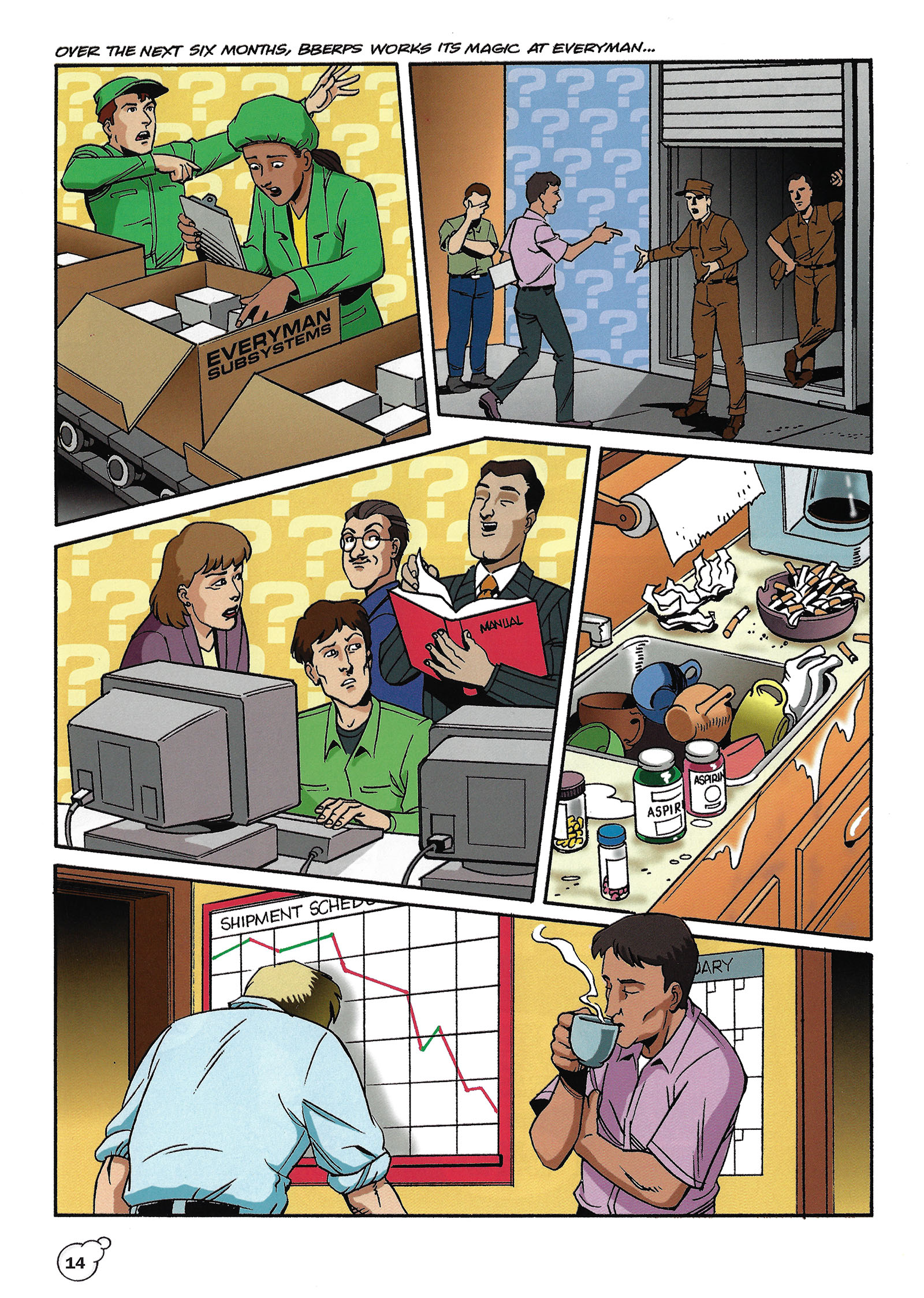

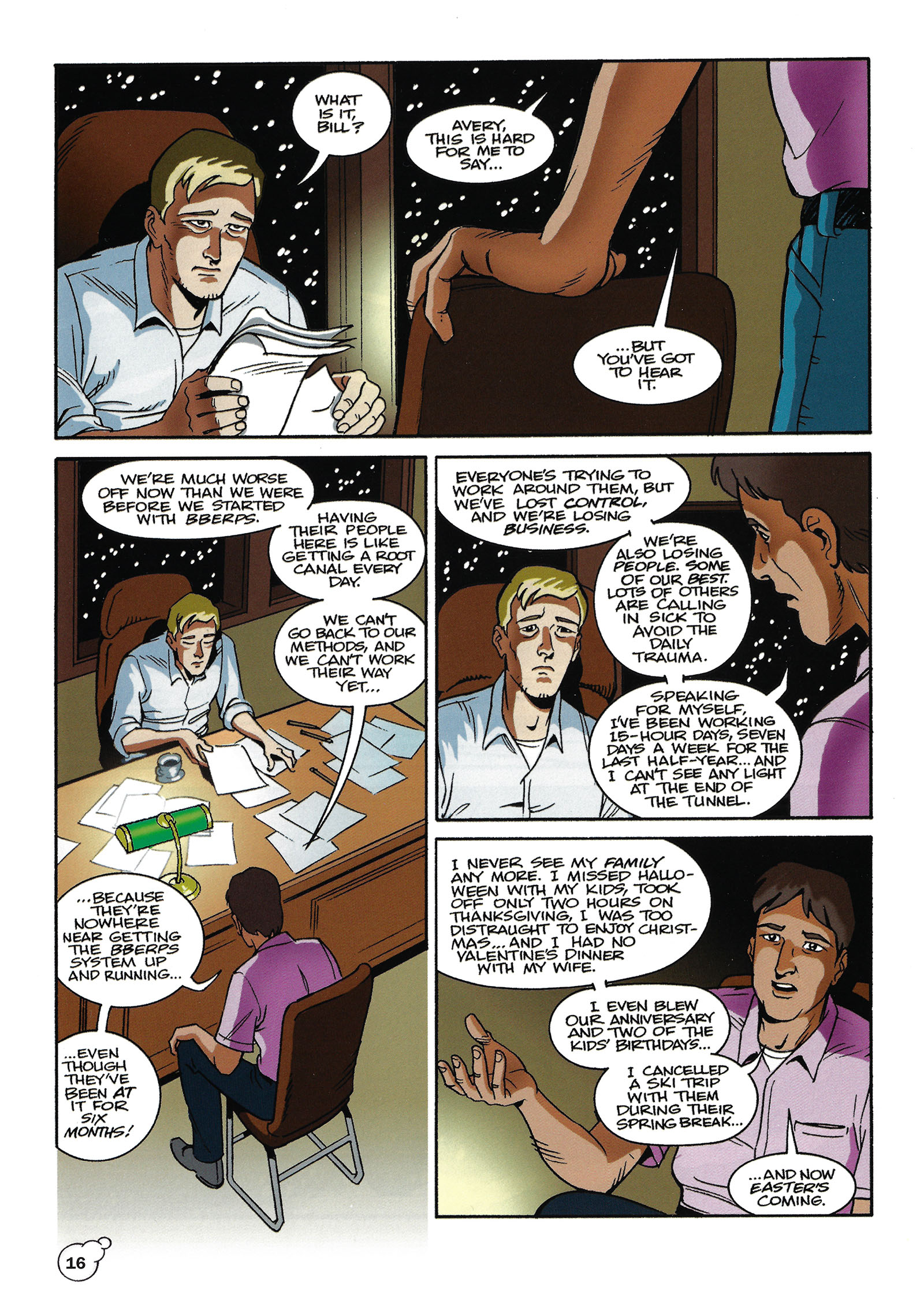

On the other hand, manga was still quite new to the American scene, and I didn’t think an annual report was the right platform to go hog wild with wacky, kinetic manga techniques. They wouldn’t mesh well with Pete’s story, which was about a company falling on hard times and needing to be rescued by Dataworks. No mecha, no energy blasts, no cute teenage girls. The audience for the project would be Dataworks shareholders, who probably wouldn’t understand “manga style,” and certainly wouldn’t take it seriously. My advice was that we stick to a visual language anyone could follow, more in keeping with a Will Eisner graphic novel. Pete could still call it manga if he wanted. The important part was that it communicated clearly to its intended audience.

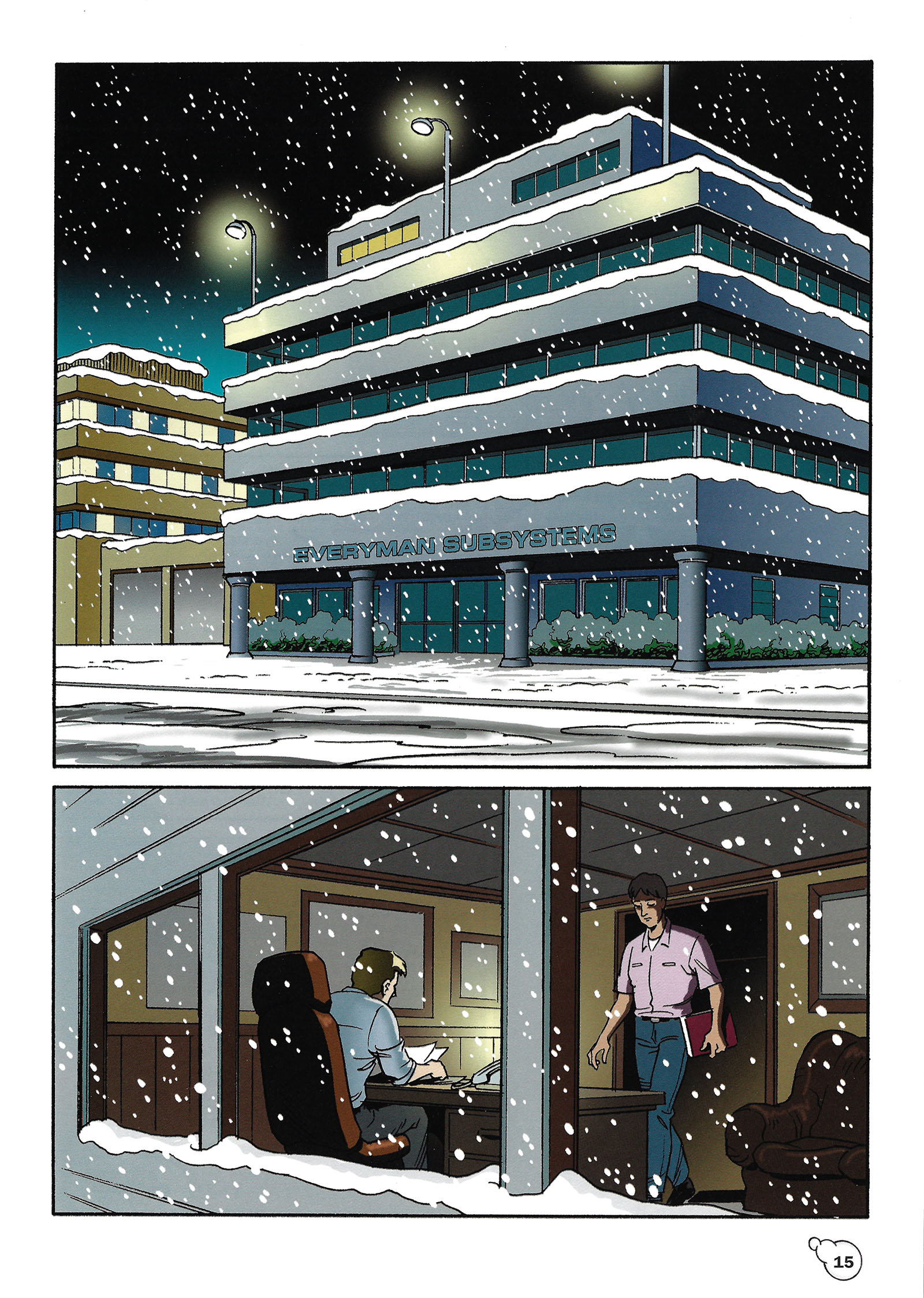

Pete wrote a solid story. I just needed to adapt his work into a script and start drawing. It came to 29 pages with me drawing and lettering, and my friend John Ott handling the color (my stuff always looks better in color). Realistically, I figured shareholders might skim it (amused), then hand it over to their kids, who would zone out after three pages. But it was a chance to draw a kind of comic I’d never drawn before. That would be my reward. And the page rate was WAY better than in the “real” comic book world.

What I liked most about the finished product was the print quality. Annual reports are a big deal, made to impress, and this was hands-down the best my work ever looked on the finished page up to that point. After all the junk printing I endured with indie comics, it was like finally being treated like an adult. (We who spend days and nights at the drawing board obsess mightily over how our labors look in the end.) The only disappointment was that my name didn’t appear anywhere on it. Neither did Pete’s, which is why I can’t remember it any more. That’s just how things go in the commercial art world.

With that, I’ll step aside and present the finished work. It’s not electrifying reading, but if you’re not careful you may learn something before it’s done.