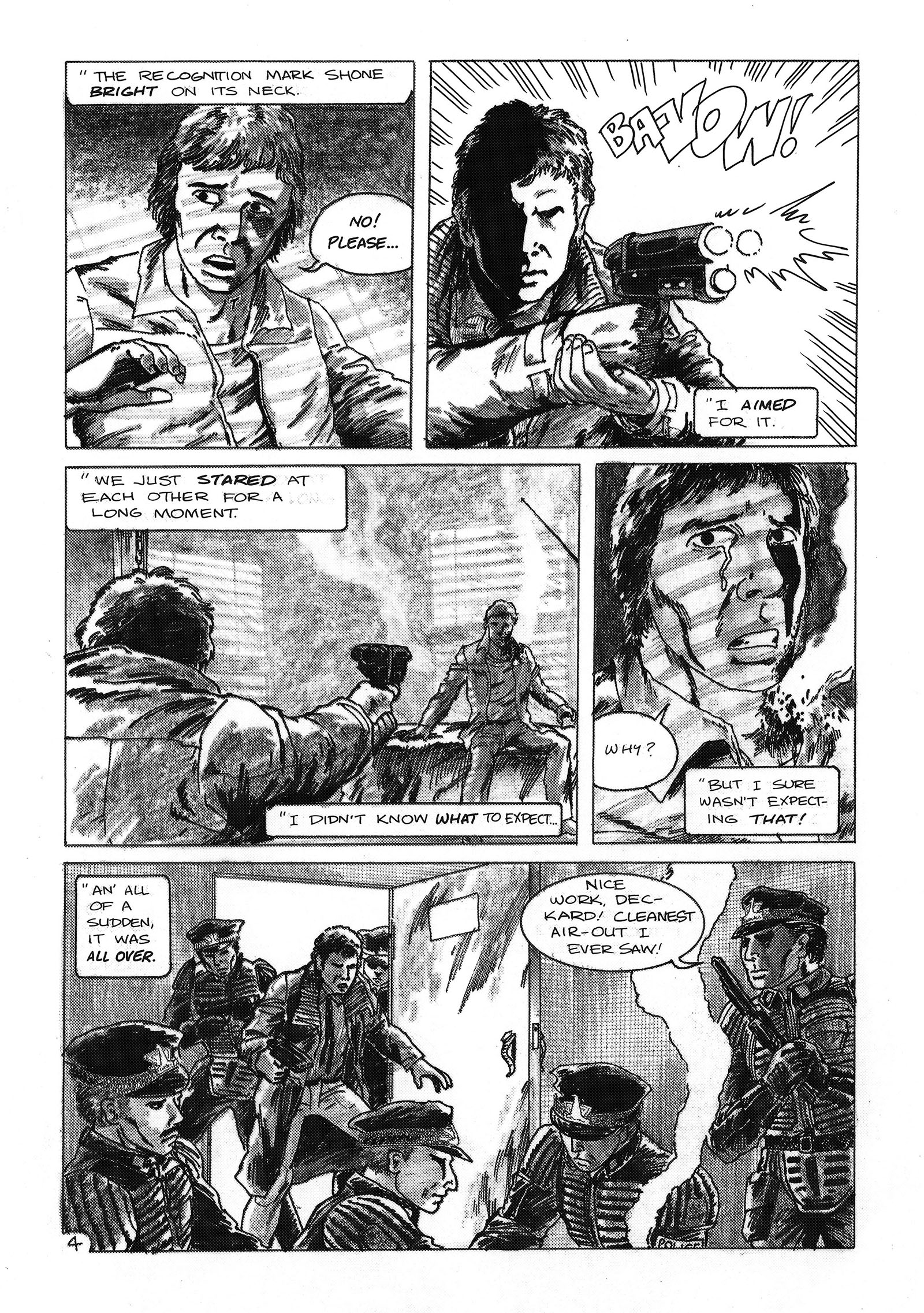

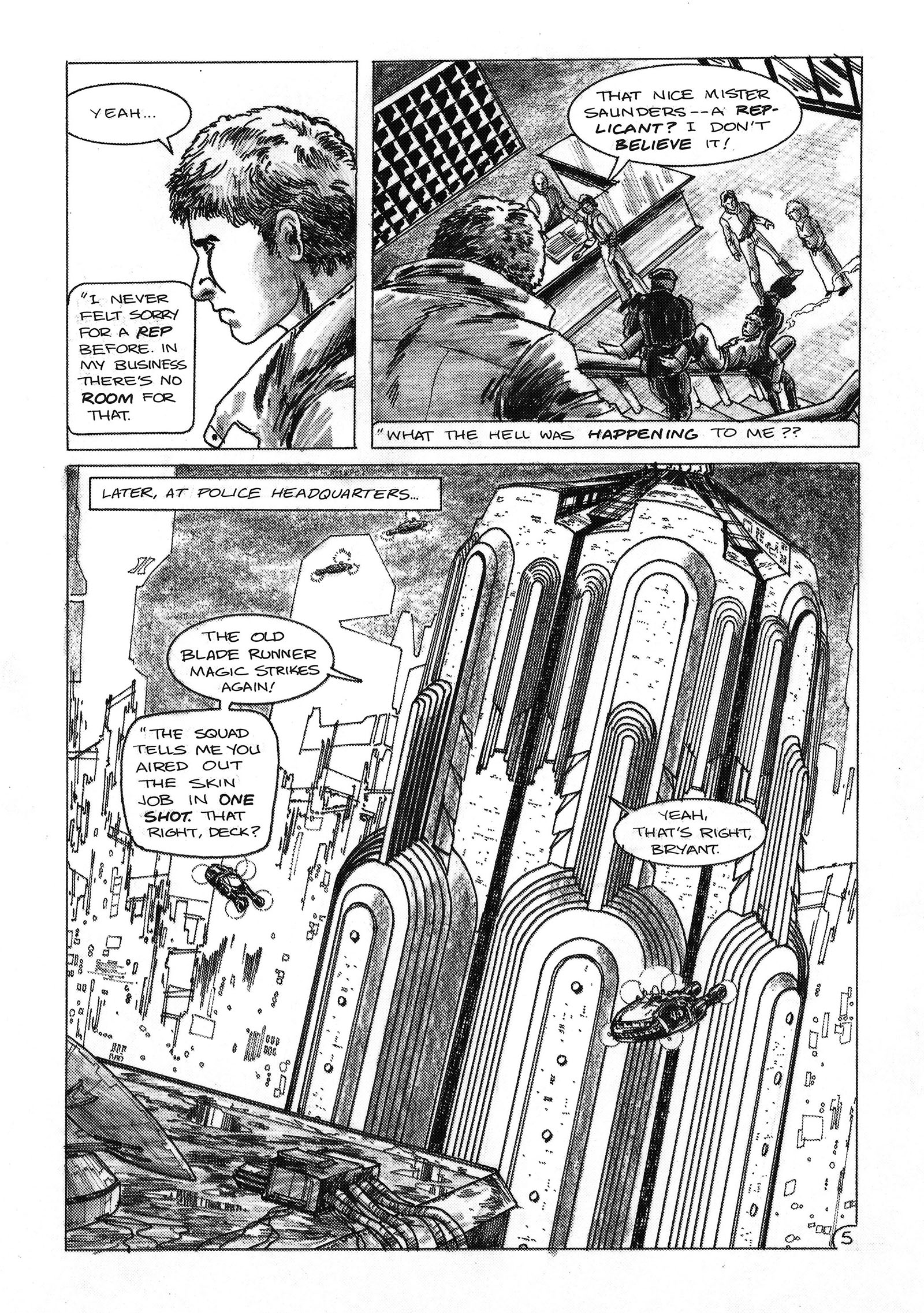

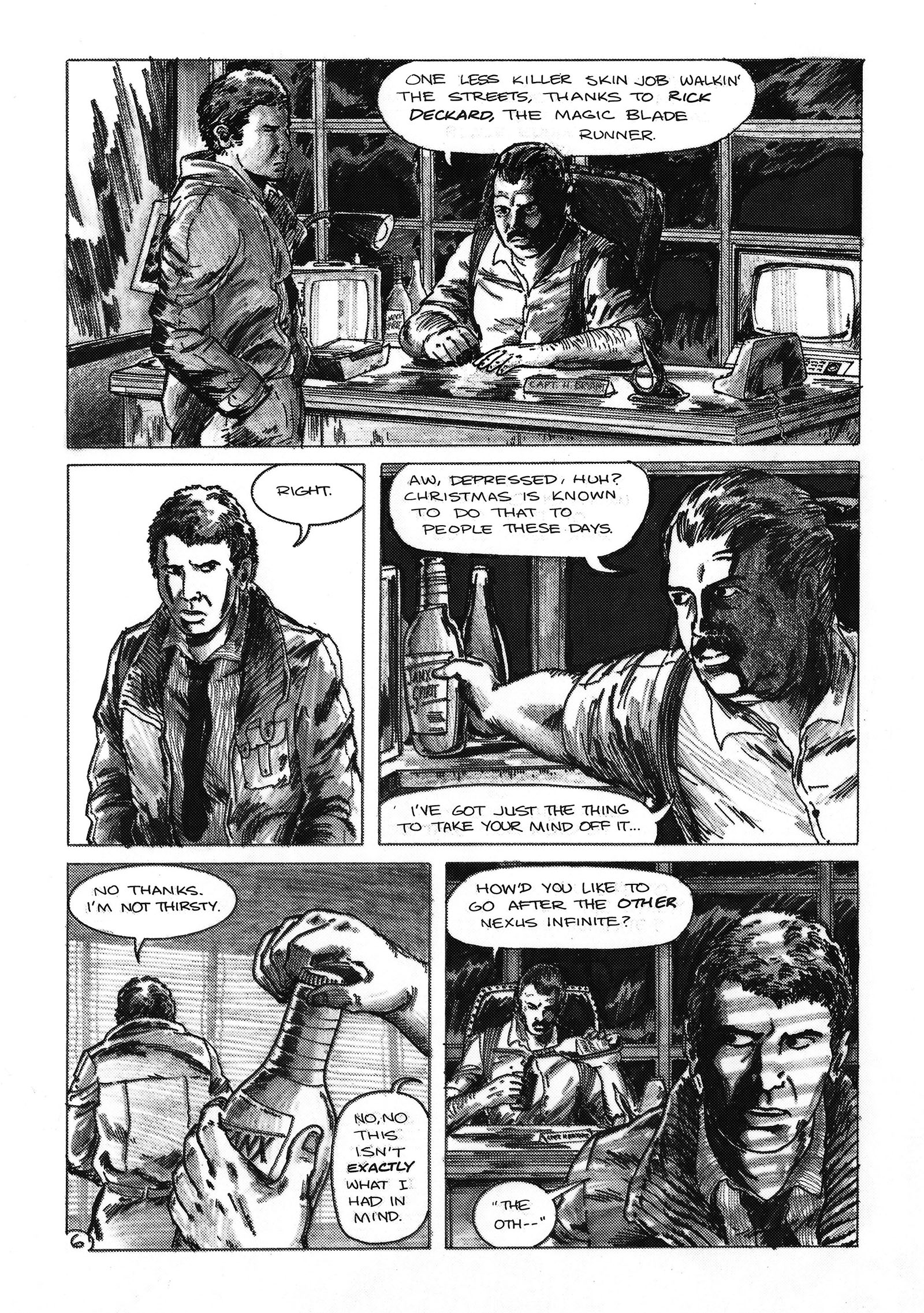

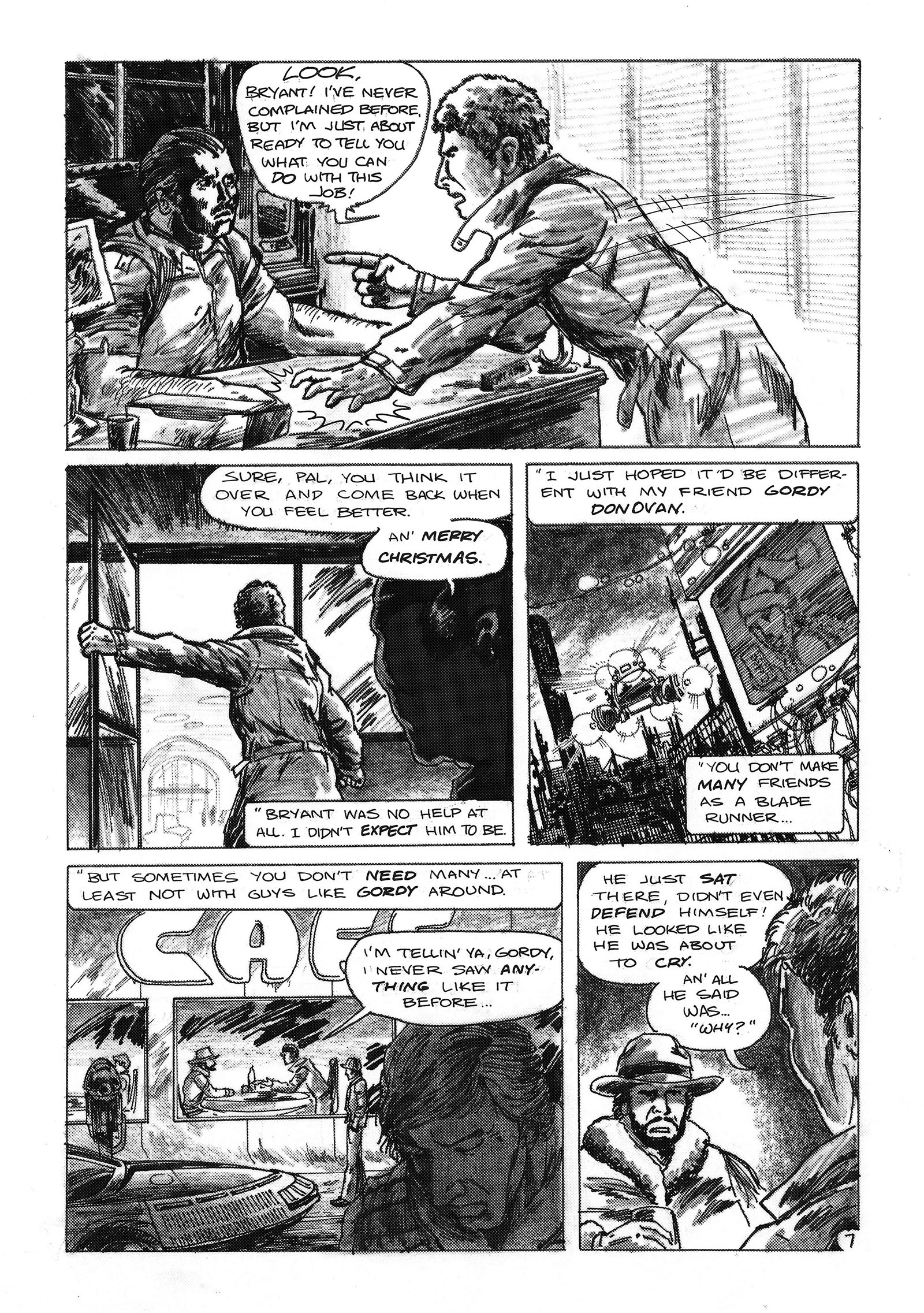

Blade Runner: Will a Soul Survive, 1983

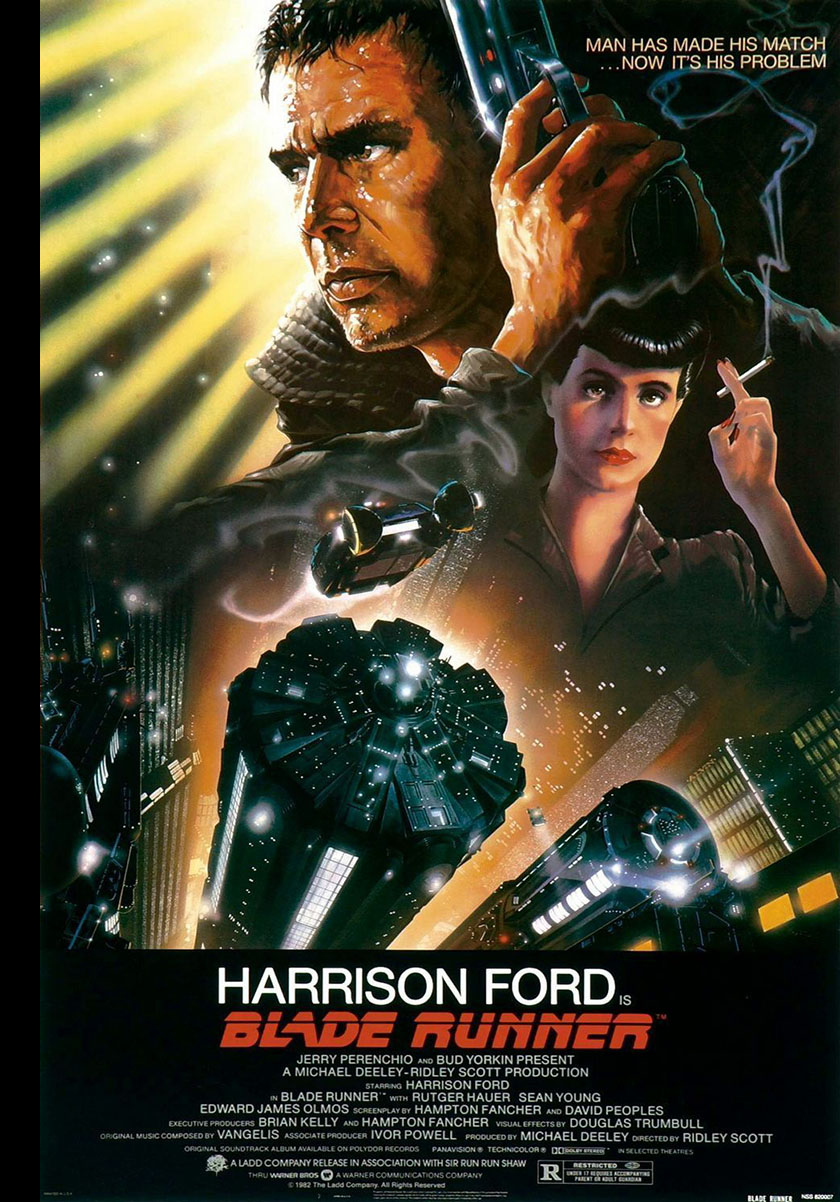

It’s hard to overstate what a breakthrough year 1982 was, for both myself and the movie biz. That was the summer I turned 17 and got my first job/car/girlfriend. It was also the year that truly paid off the gambles taken by Lucas and Spielberg in the 70s. In just a short, 4-month period, we got more A-level fantasy and SF movies than we’d ever seen before. For me, the one that rose above all the others was Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

I can still remember exactly what it felt like to see it for the first time. It was transformative, like the first taste of a meal or the first chord in a song you know is going to be a favorite for the rest of your life. In an instant, it enlarged my understanding of what visual storytelling could accomplish. It did what all the best things in life do: it made my world bigger.

When I went back to high school that fall for my senior year, I felt like a different person. Because I’d spent the summer in the company of adults rather than teenagers, both at work (in an animation studio) and in movie theaters, I saw completely past my immediate horizon into the future that was waiting for me. High school had shrunk from an infuriating obstacle course to a tedious setback.

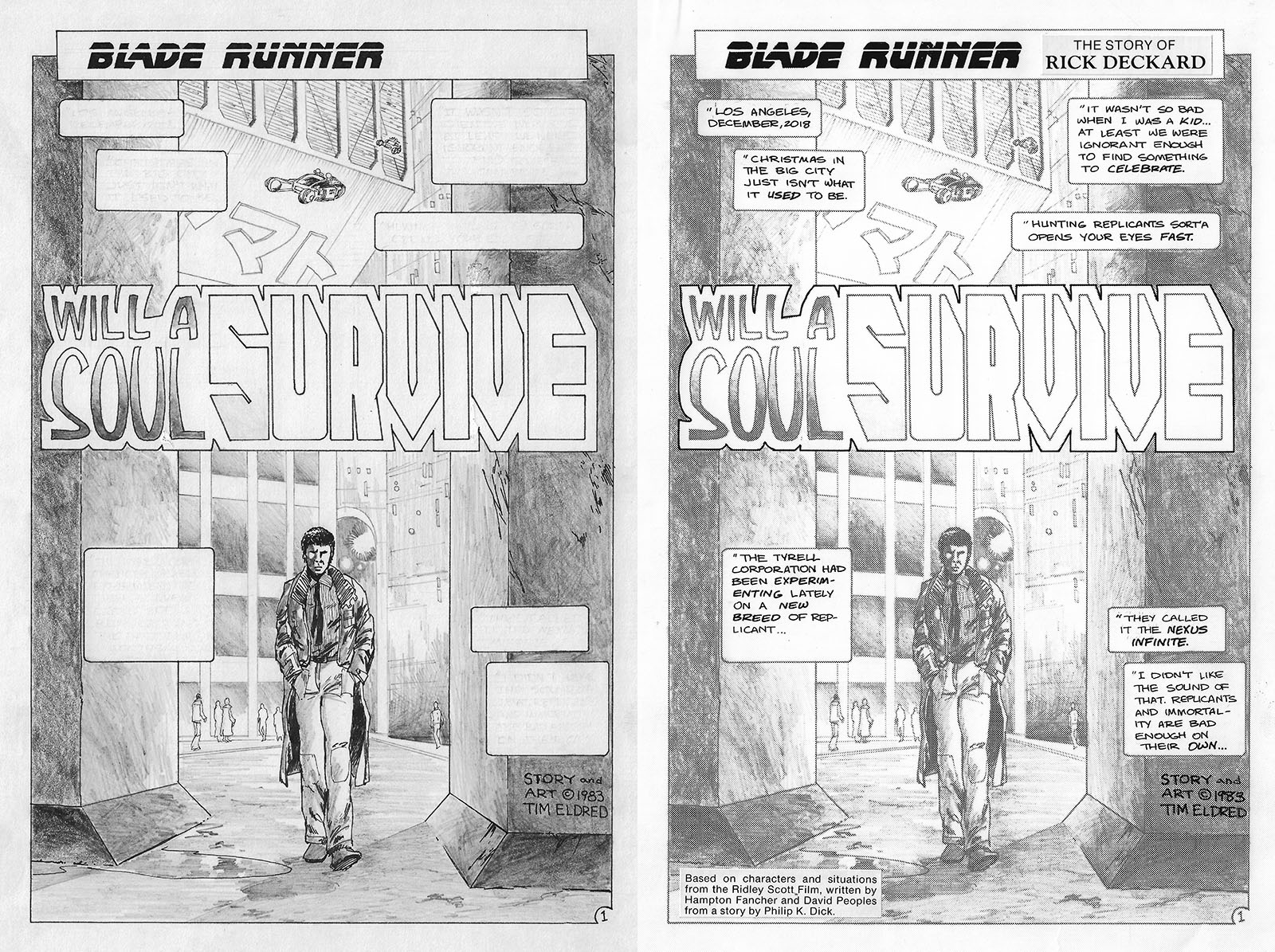

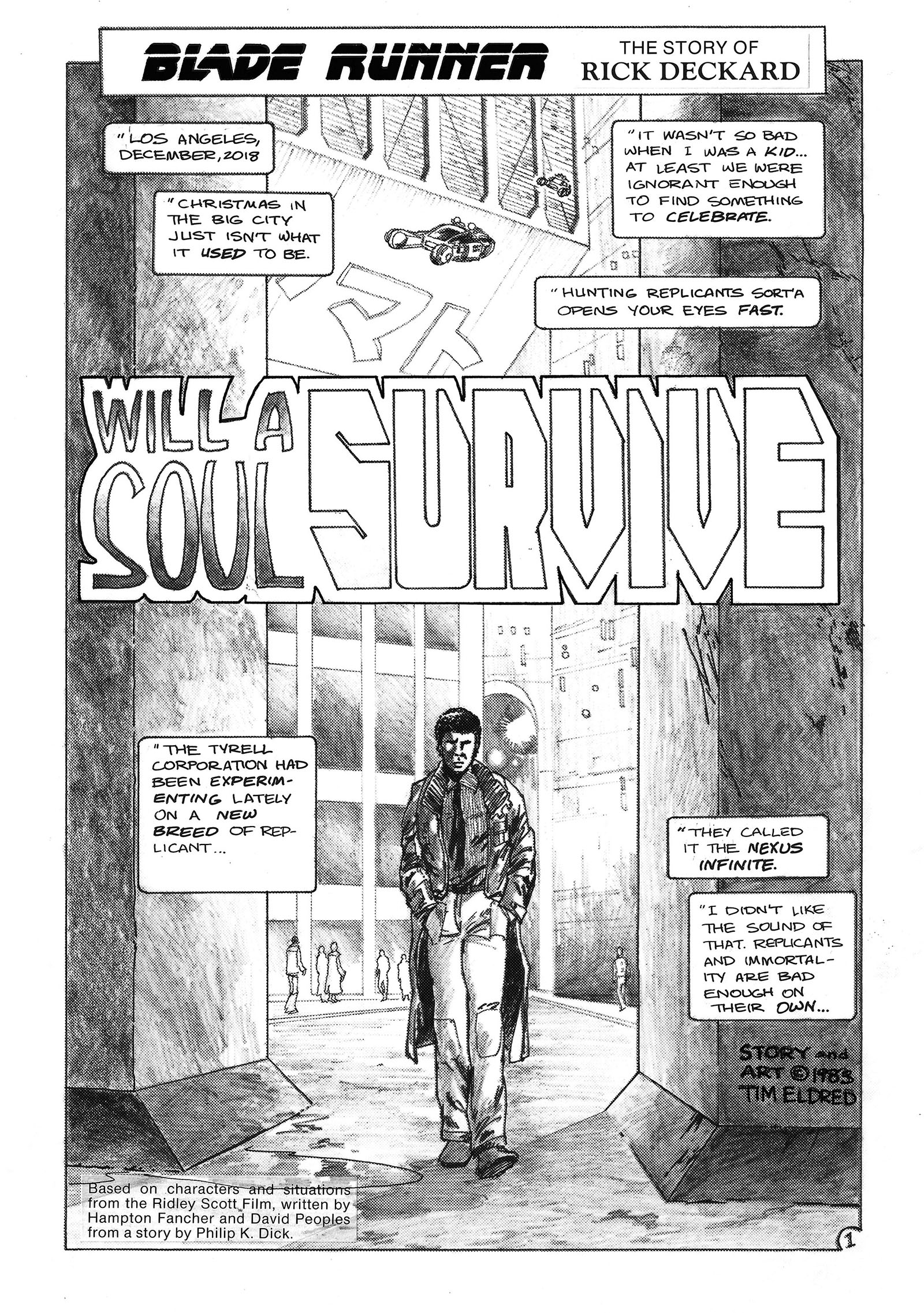

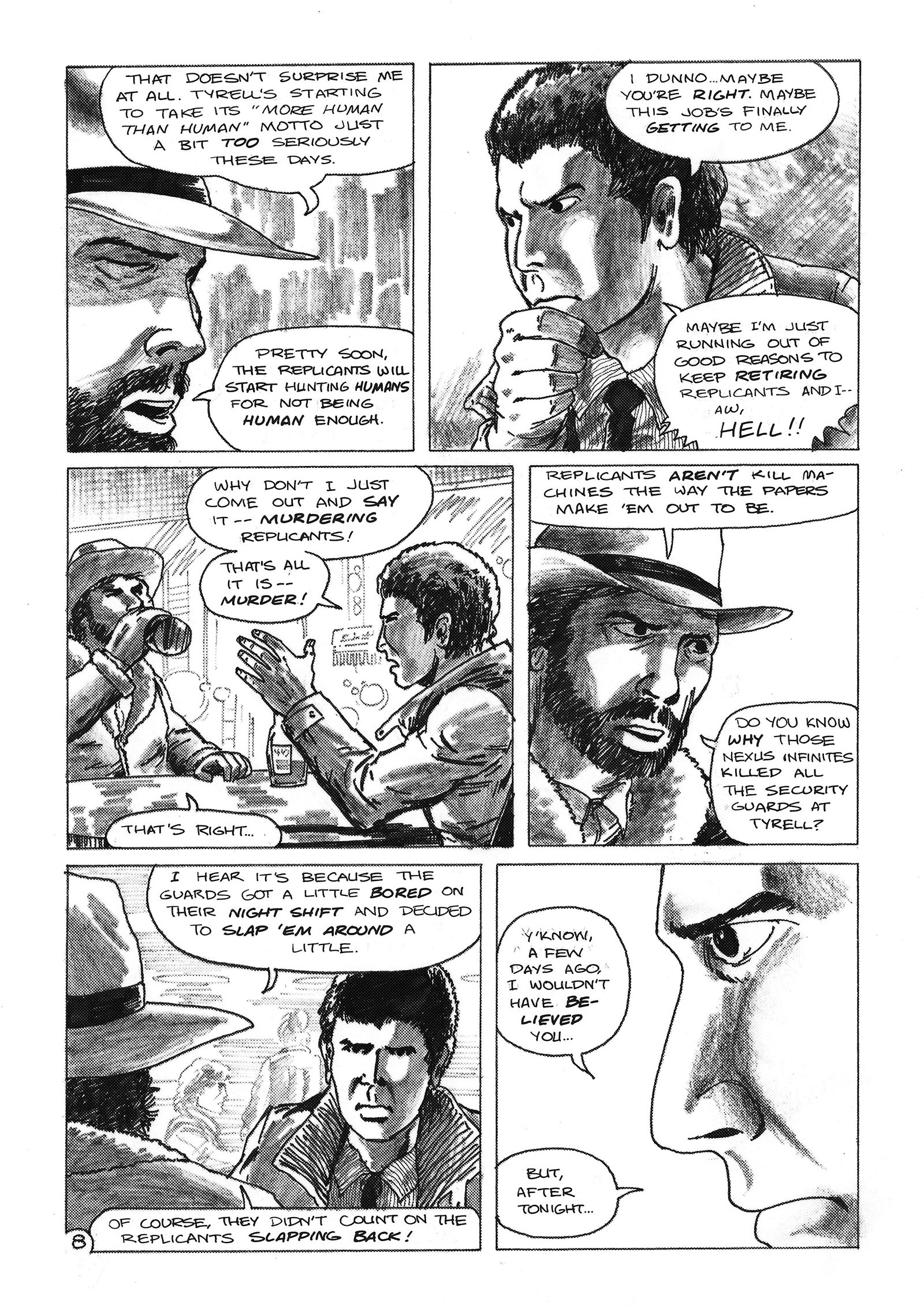

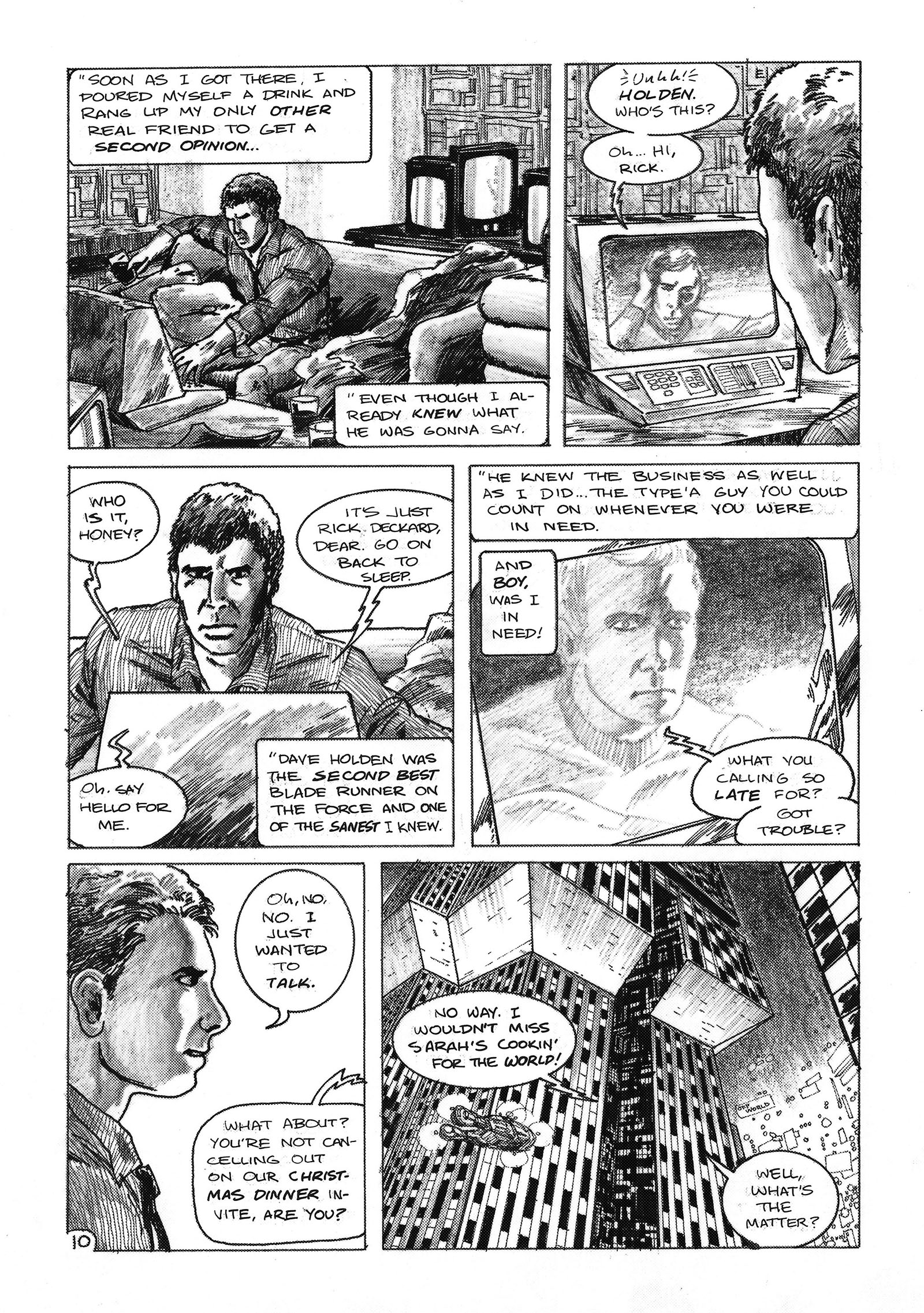

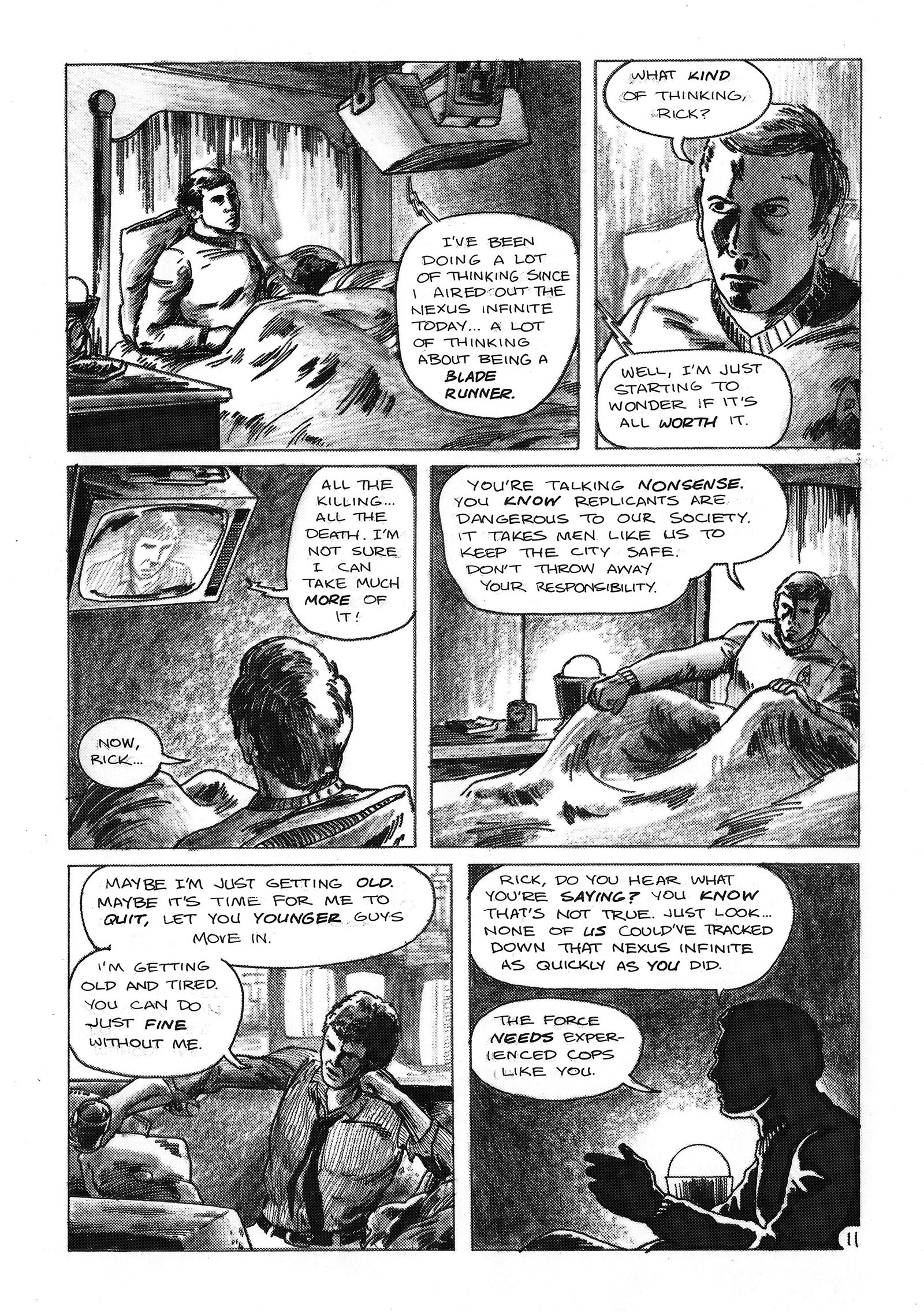

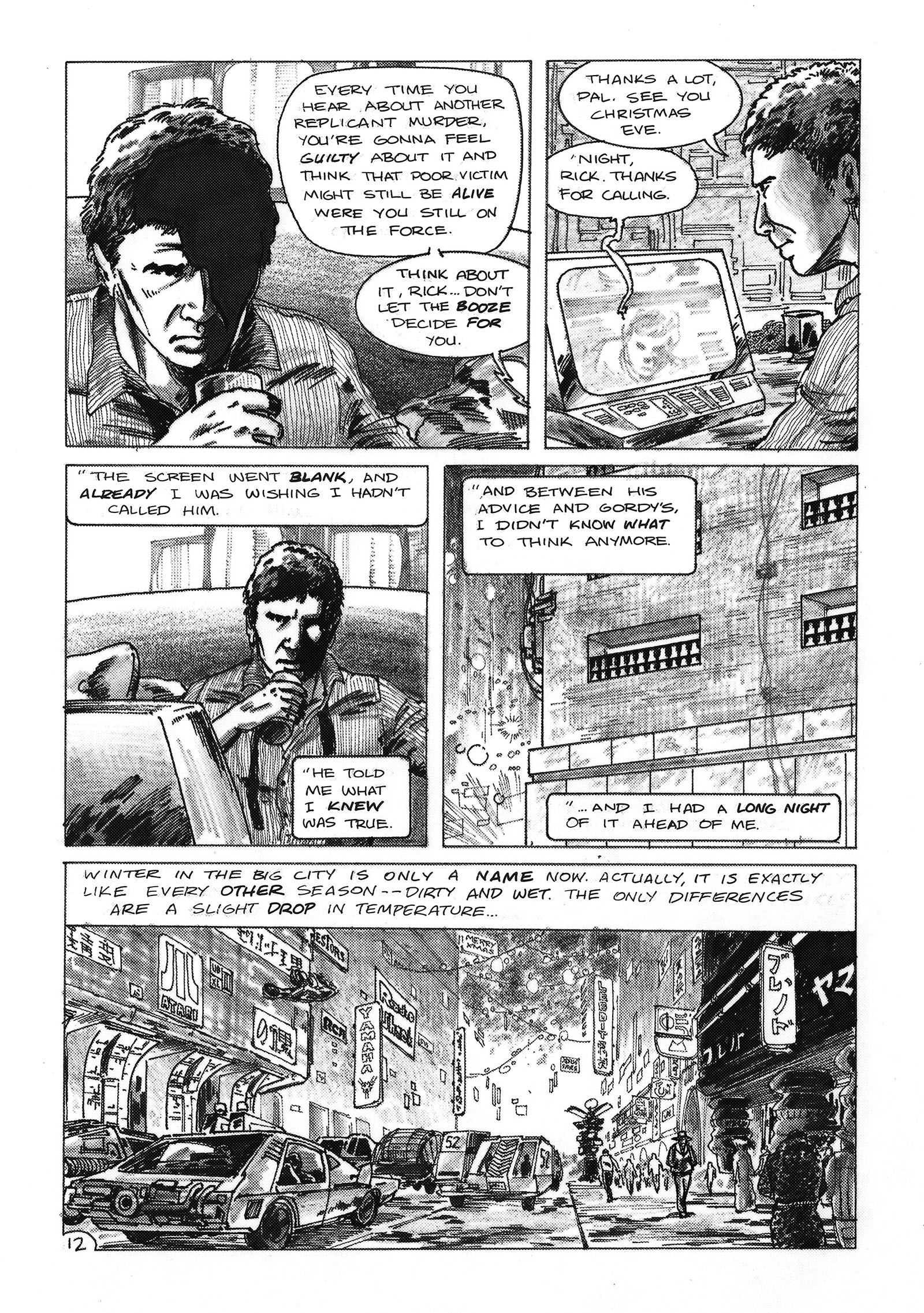

Meditating on Blade Runner was one of things that propelled me through that final year, and it had gotten so deep into my bloodstream that it had to come out as a fanzine comic. But it couldn’t look like another Star Wars story; It had to honor the texture and depth that made it so unique. I was still drawing Star Wars and wouldn’t give it up any time soon (Return of the Jedi was still coming, after all), but a Blade Runner comic had to be different somehow. Thanks to a full year of commercial art training and my mother’s day job in print media, I had an idea for how to accomplish this.

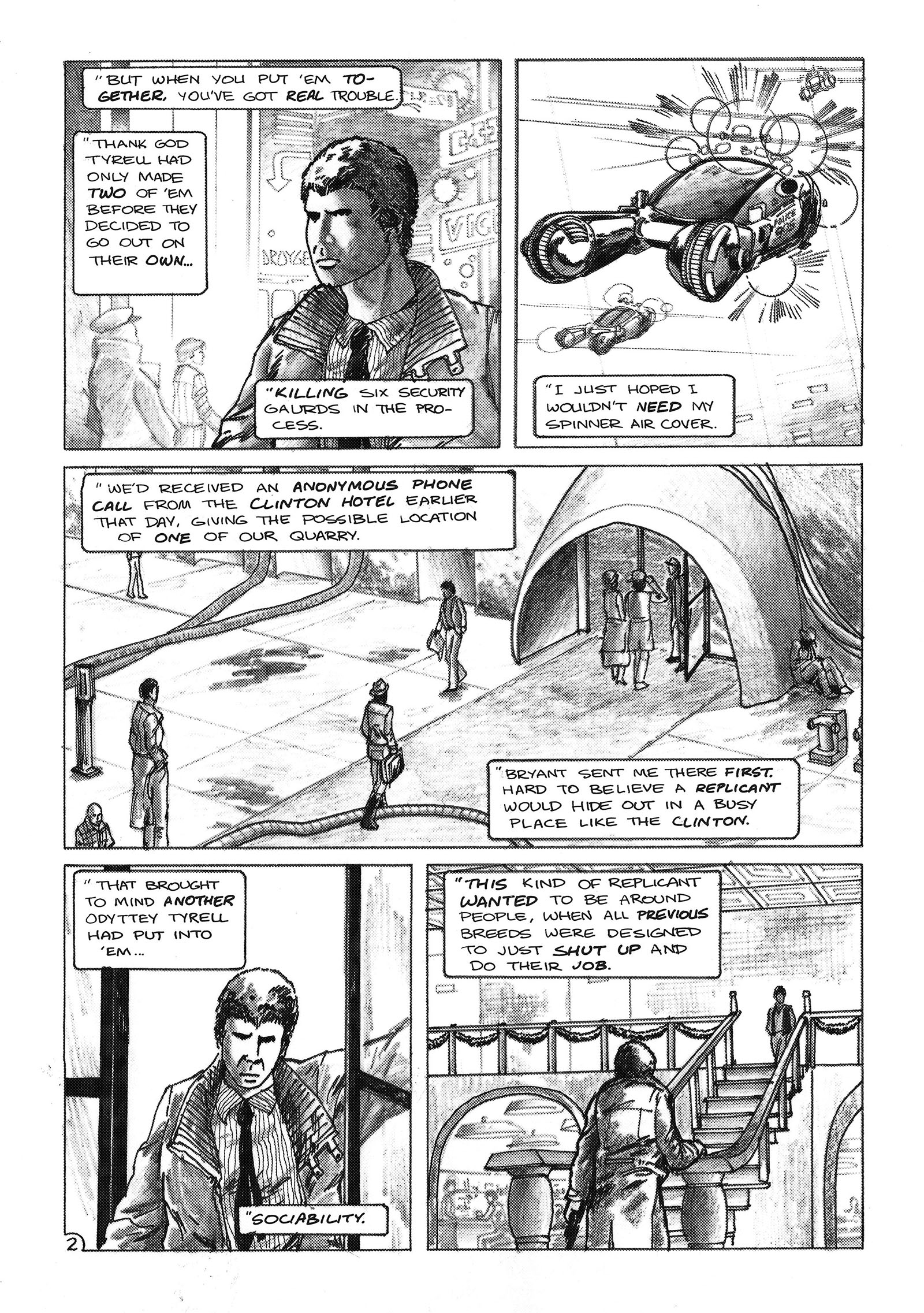

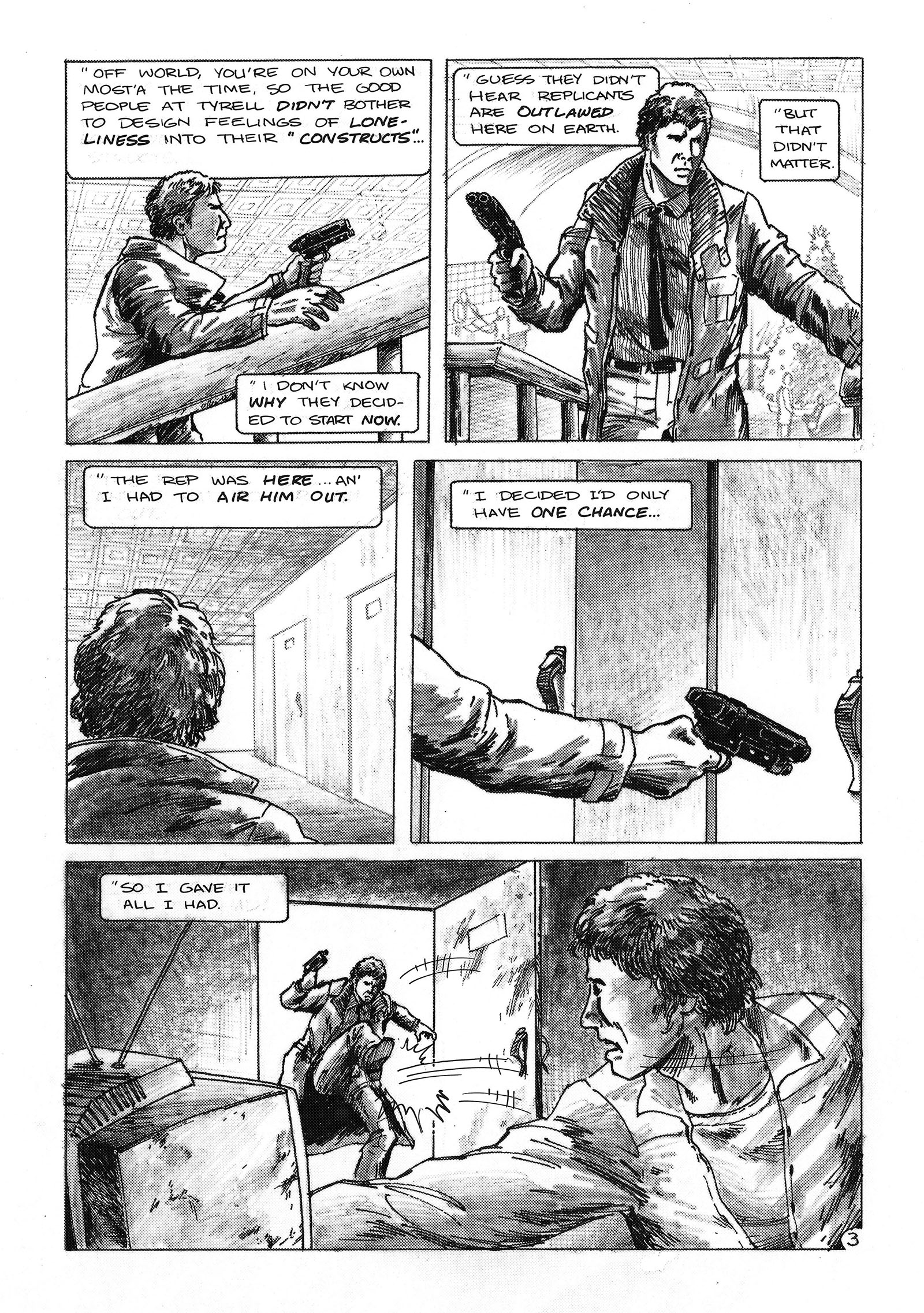

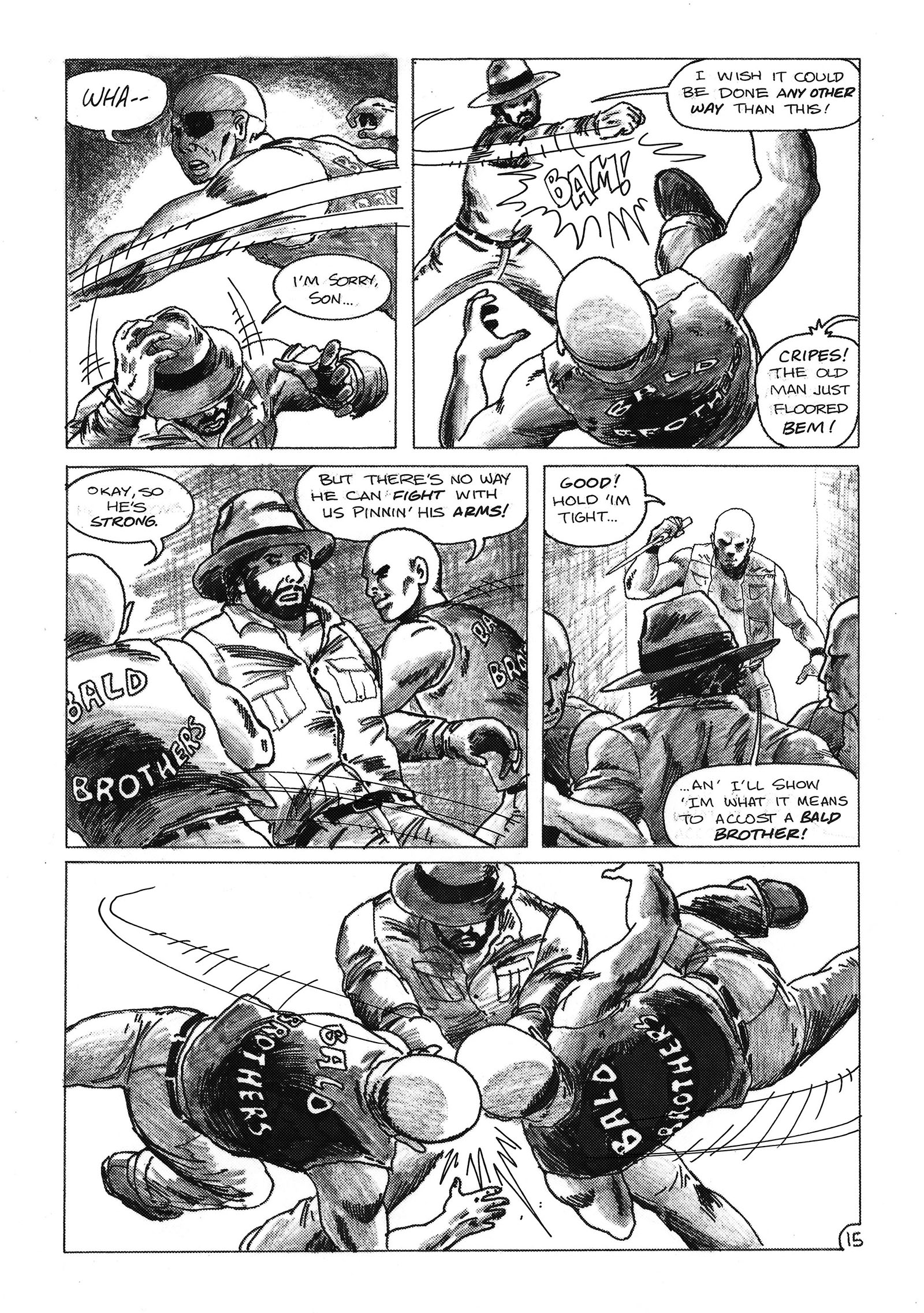

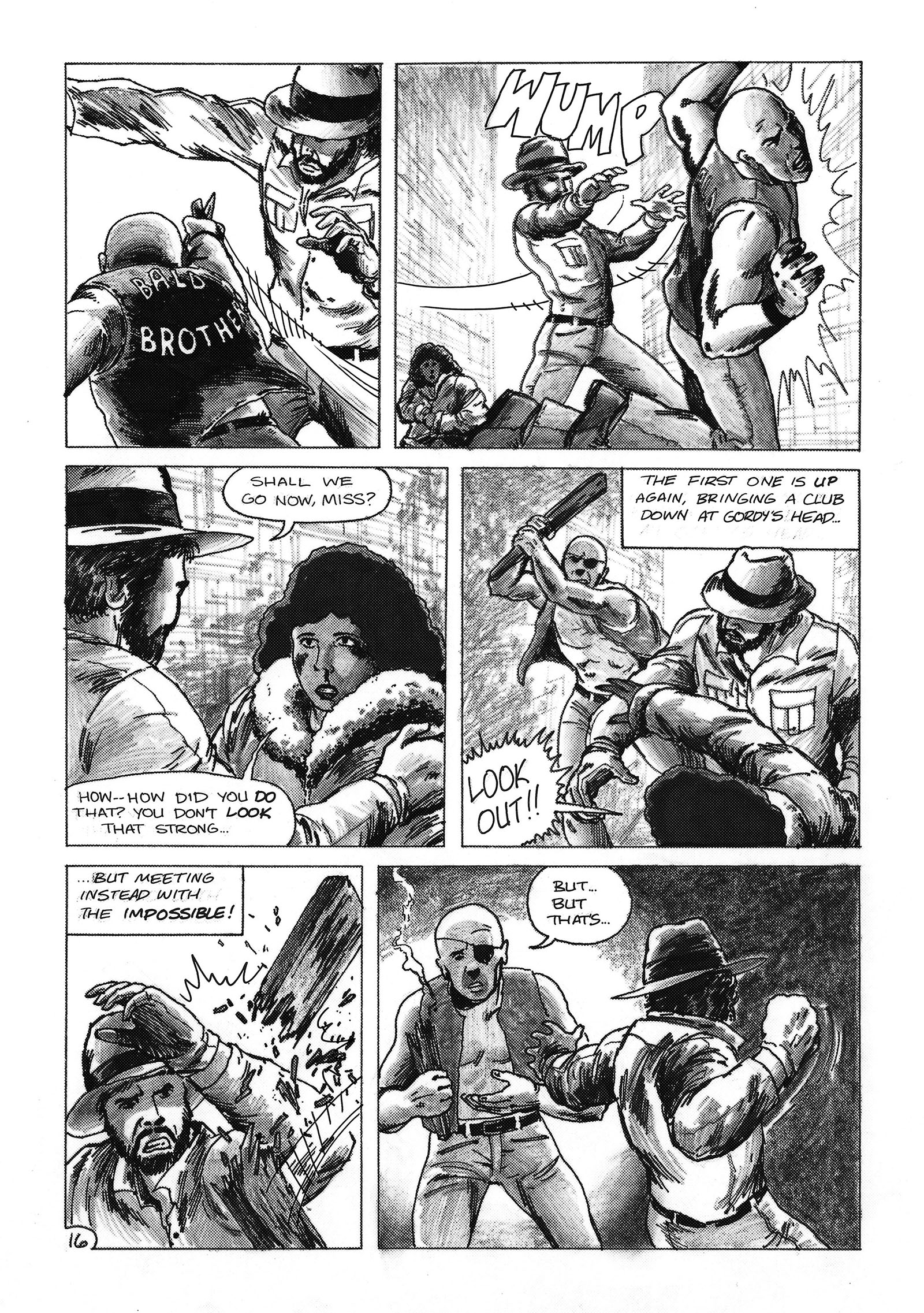

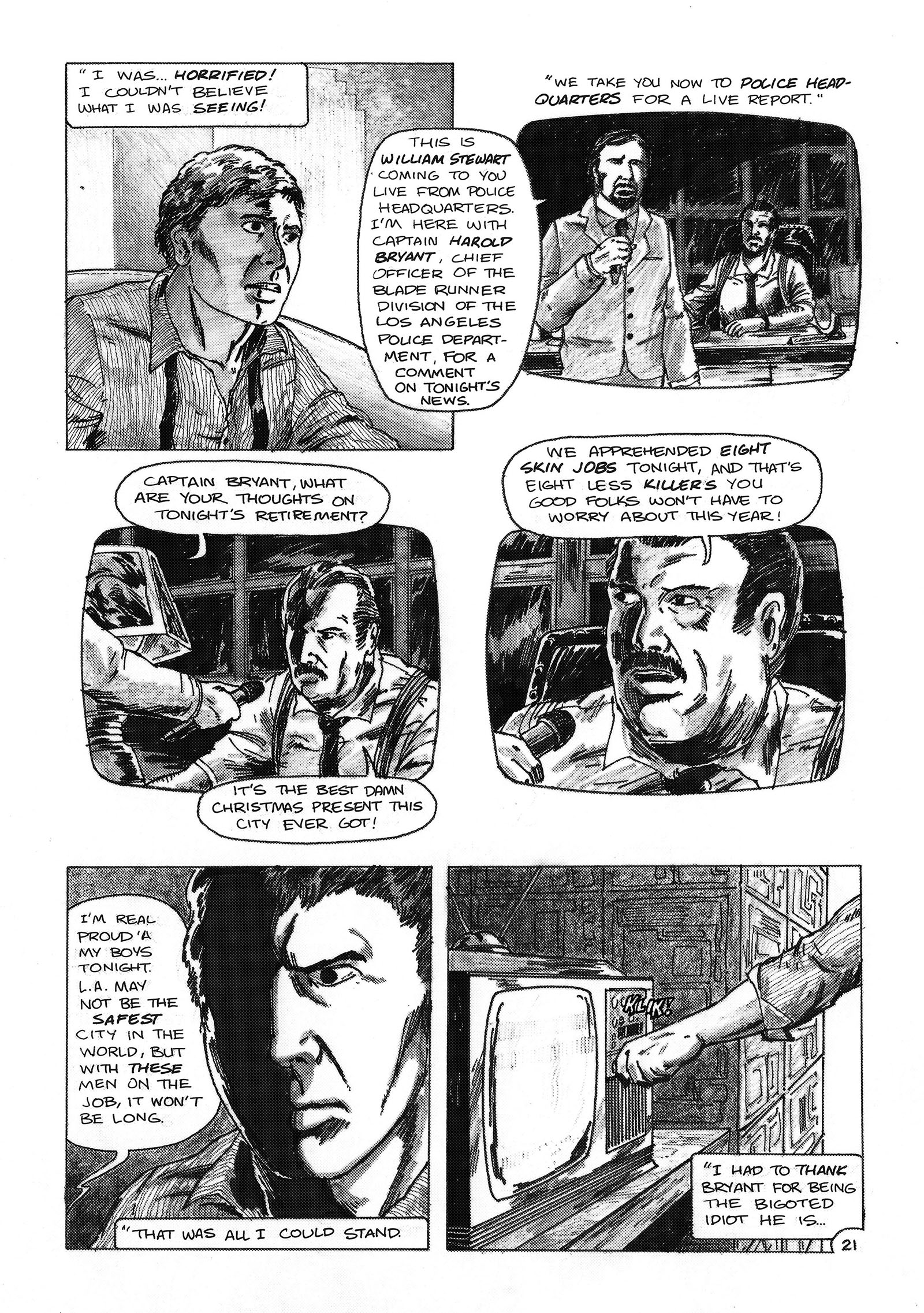

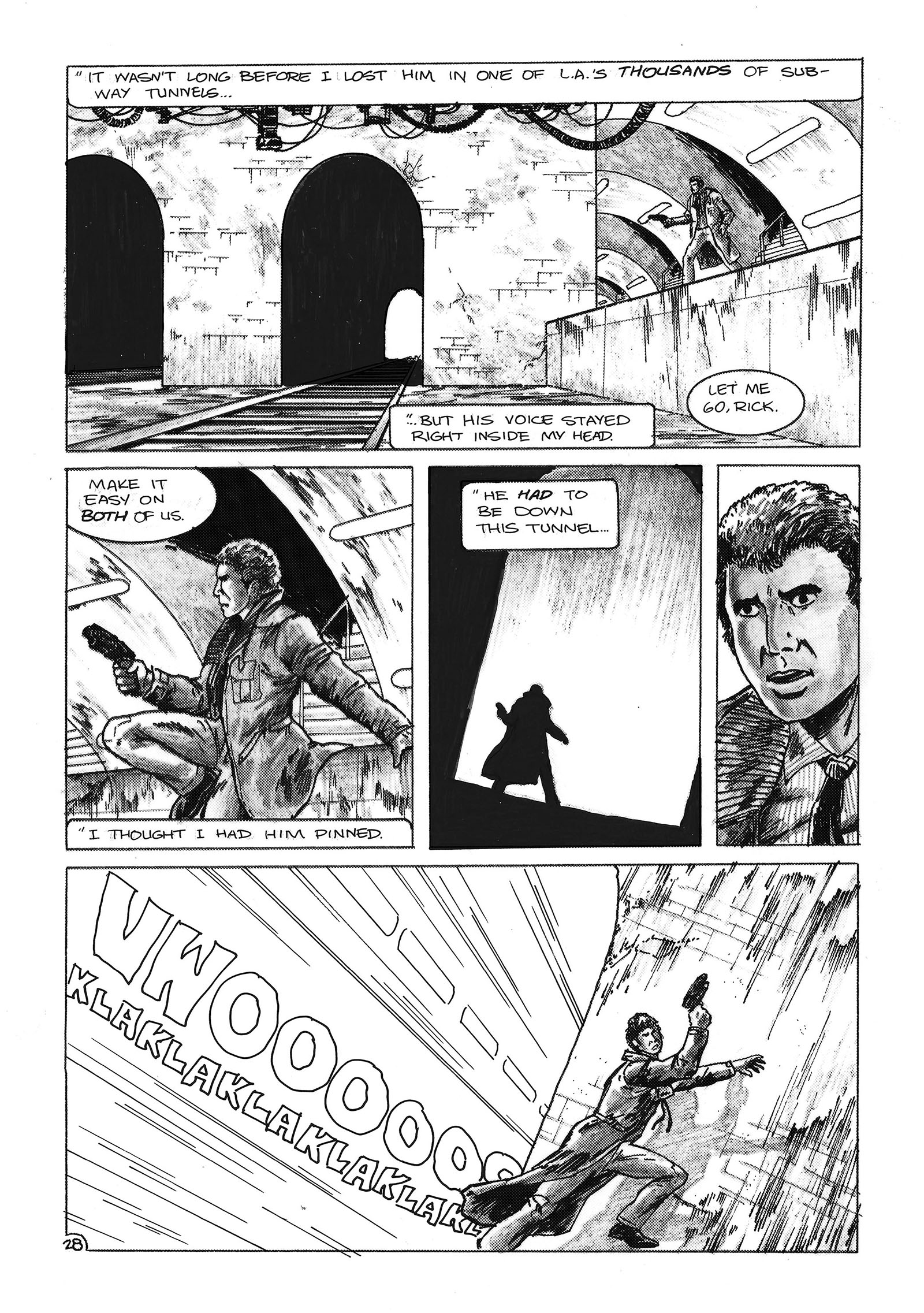

I couldn’t just draw with ink. For texture and shading, you need a pencil. The problem was, to capture the subtlety of grey tones in the cheap offset printing of a fanzine, they had to be converted into black and white screen tones. This process is called “halftoning.” The simplest way I can explain it is this: you put a transparent dot-pattern screen between your original art and a camera lens (I’m talking about a photostat camera here), then expose the image onto photo paper for a specific amount of time. This turns tones into dots. Dark grey becomes large dots, light grey becomes smaller dots. When you look closely at a photo in a newspaper, you’ll see all the dots. It’s a non-issue for computer screens, but when you want to put ink on paper, This Is The Way.

My mom agreed to take my art to her office and have it converted into halftone photostats, seeing it as a way to support my continued education, so that was my green light. As I drew this story, I put much more time and thought into lighting and texture than usual. I can’t say the writing was transcendent, or that I was anywhere close to mastering my figure drawing, but adding these new flavors made this project unlike anything else I did during those years.

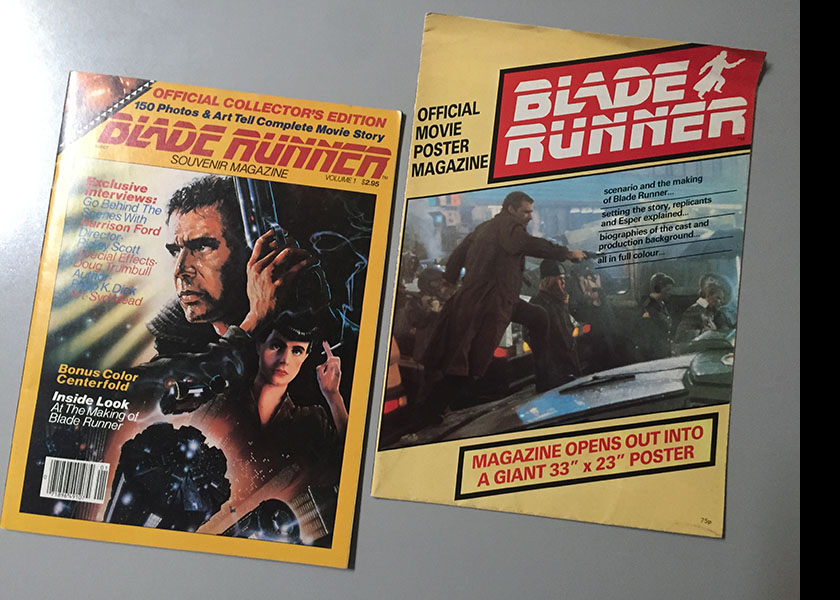

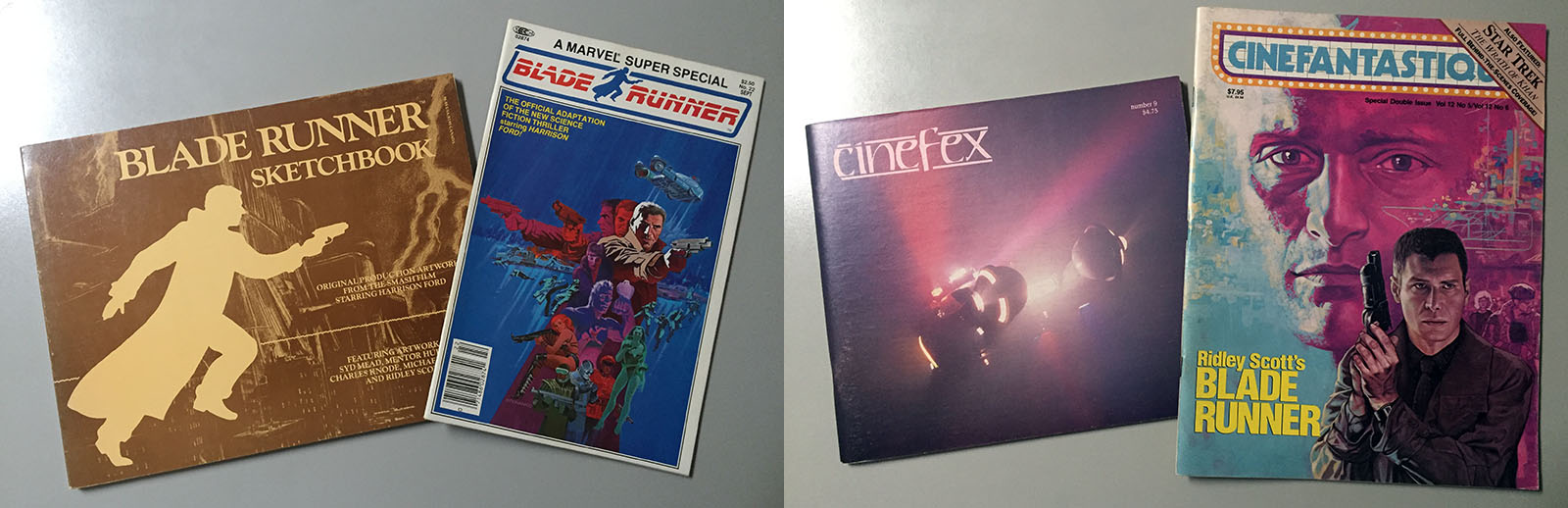

Above and below: the magazines that got me through 1982 after the film closed. But home video wasn’t far away.

Of course, nothing this experimental is going to meet 100% of your expectations. The halftoning preserved the greys, but also turned solid black into greys. So all the solid black silhouettes had to be filled in later. And the lettering would no longer be readable, so that had to be added in the final stage. This meant I couldn’t letter it with as much precision as I was used to, so it came out a bit sloppy. But it was readable, and that’s what counted.

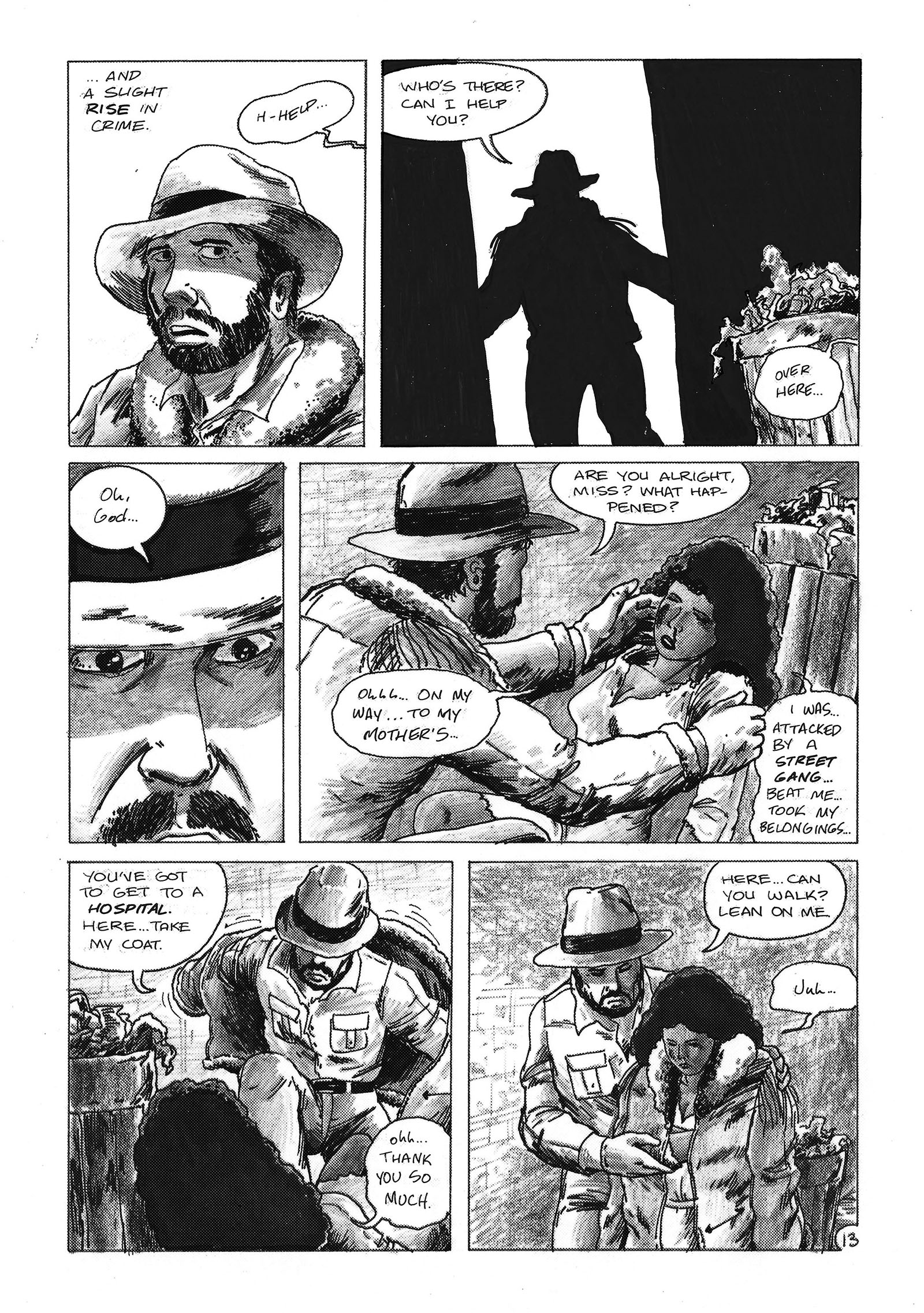

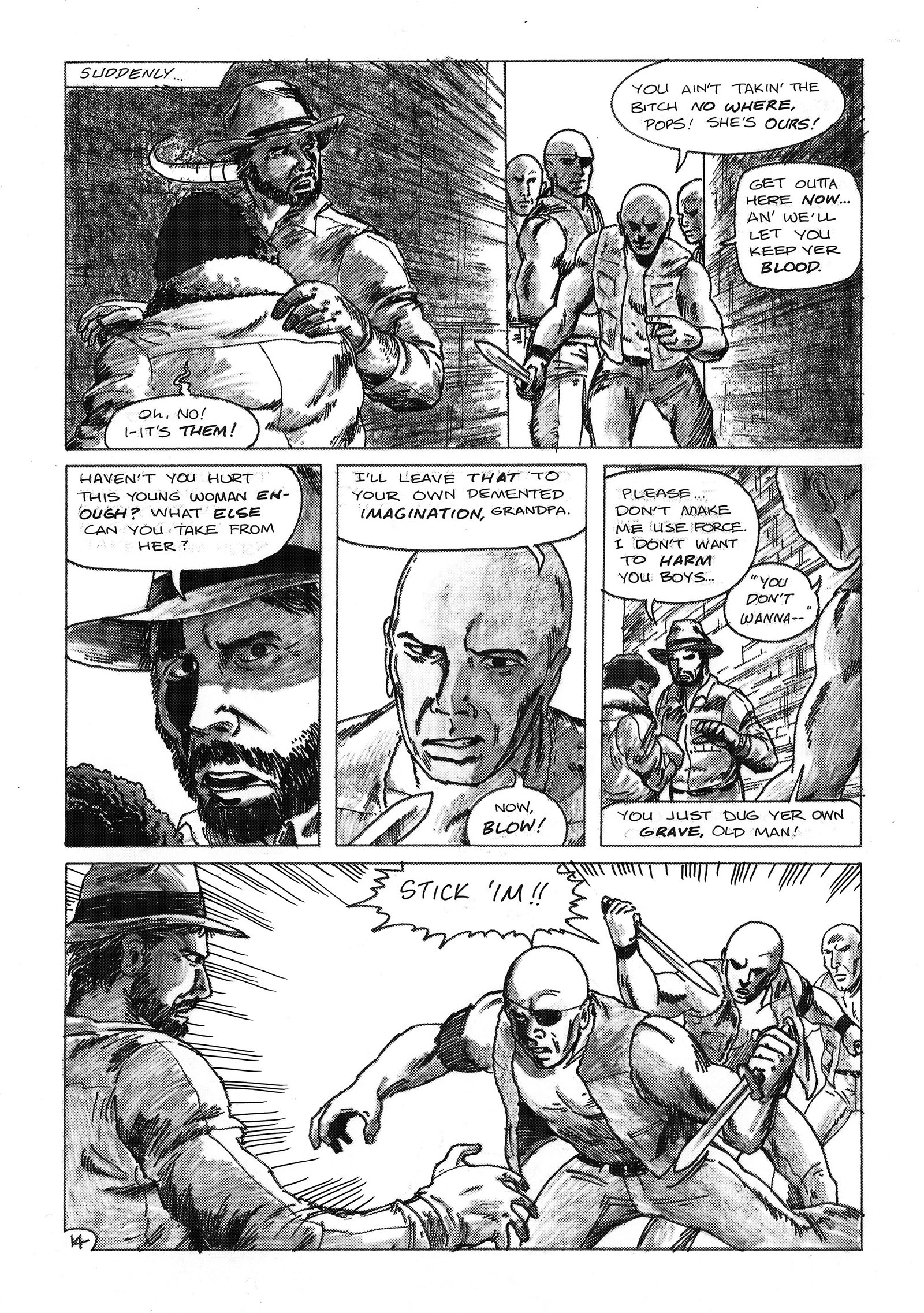

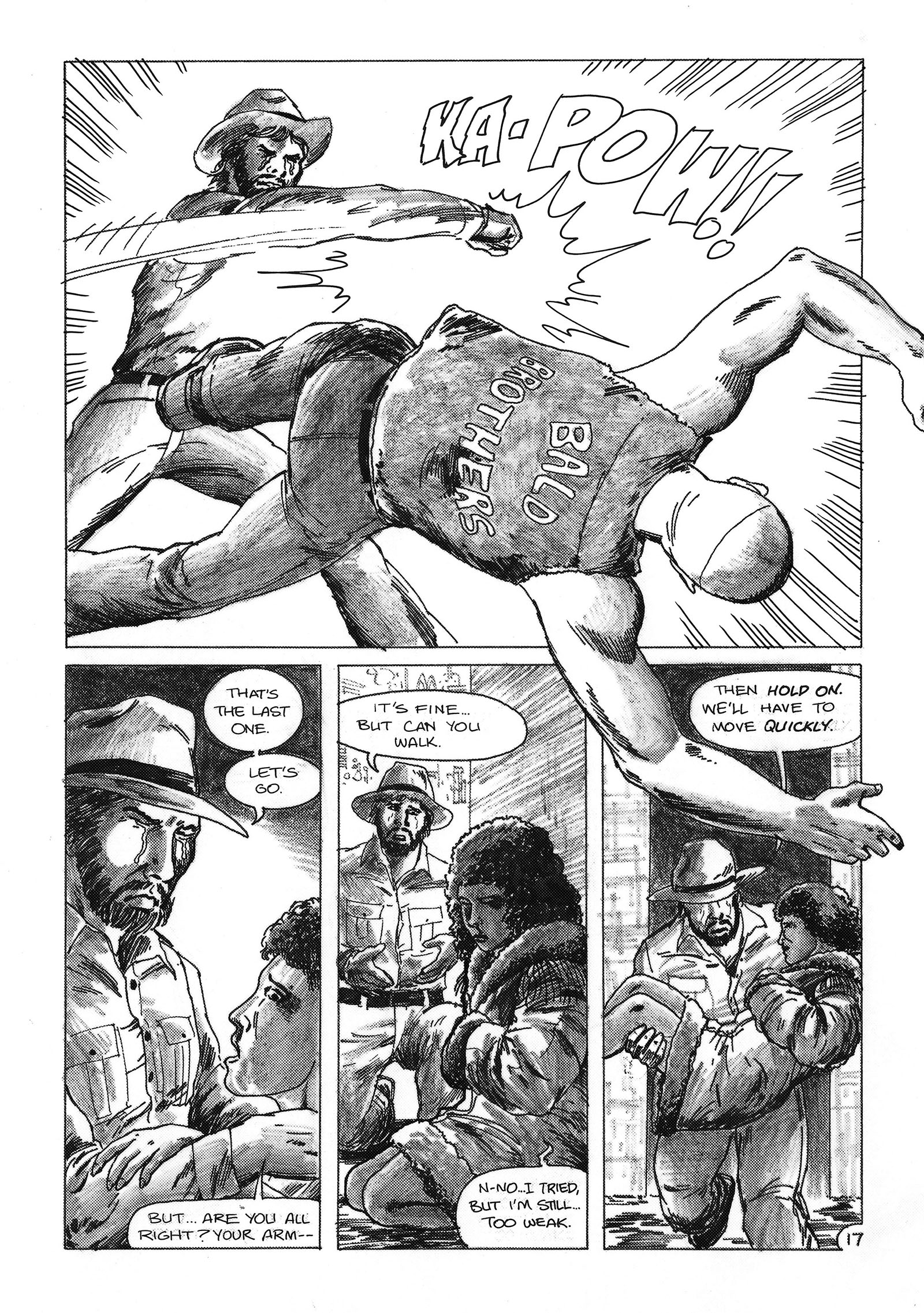

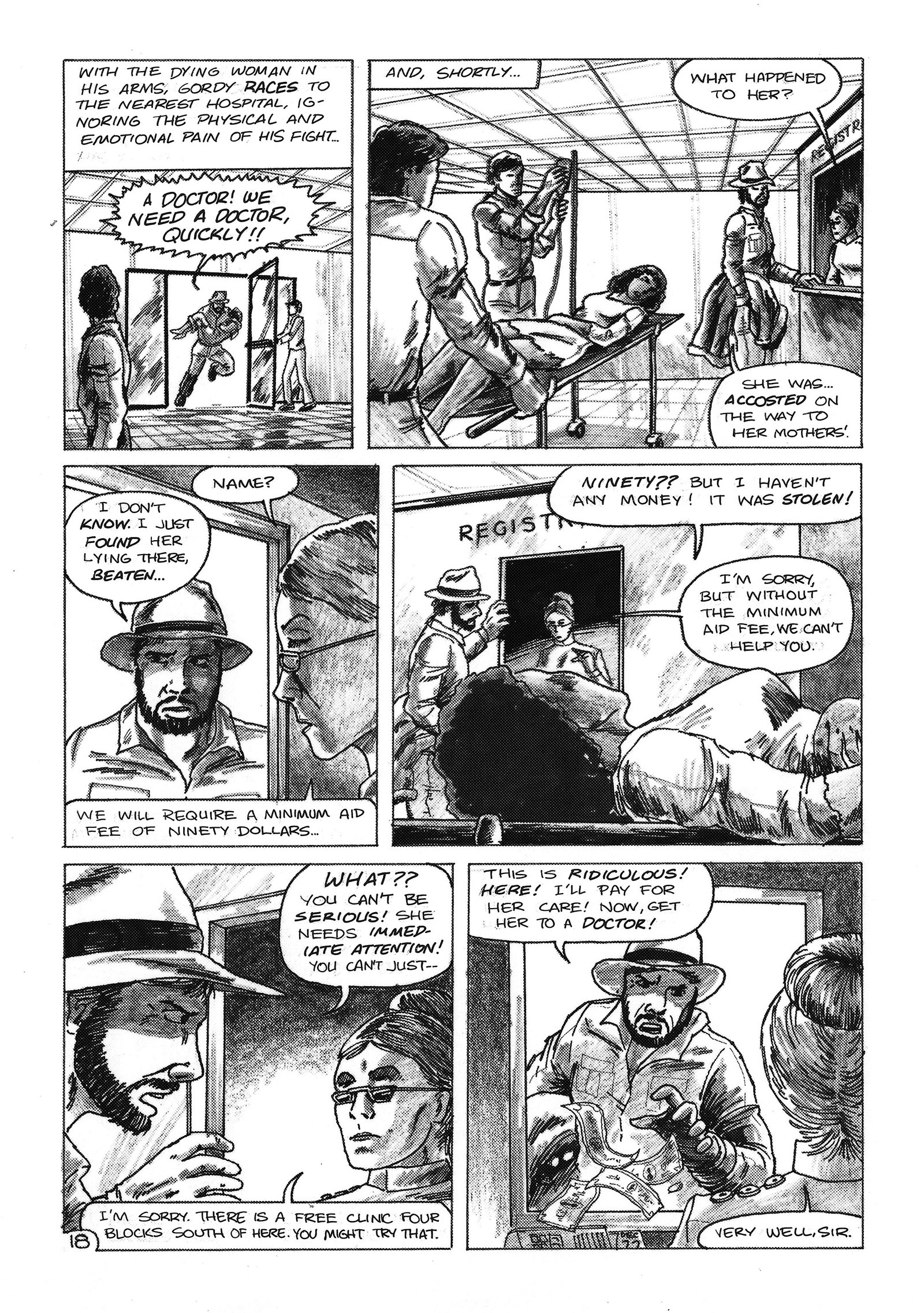

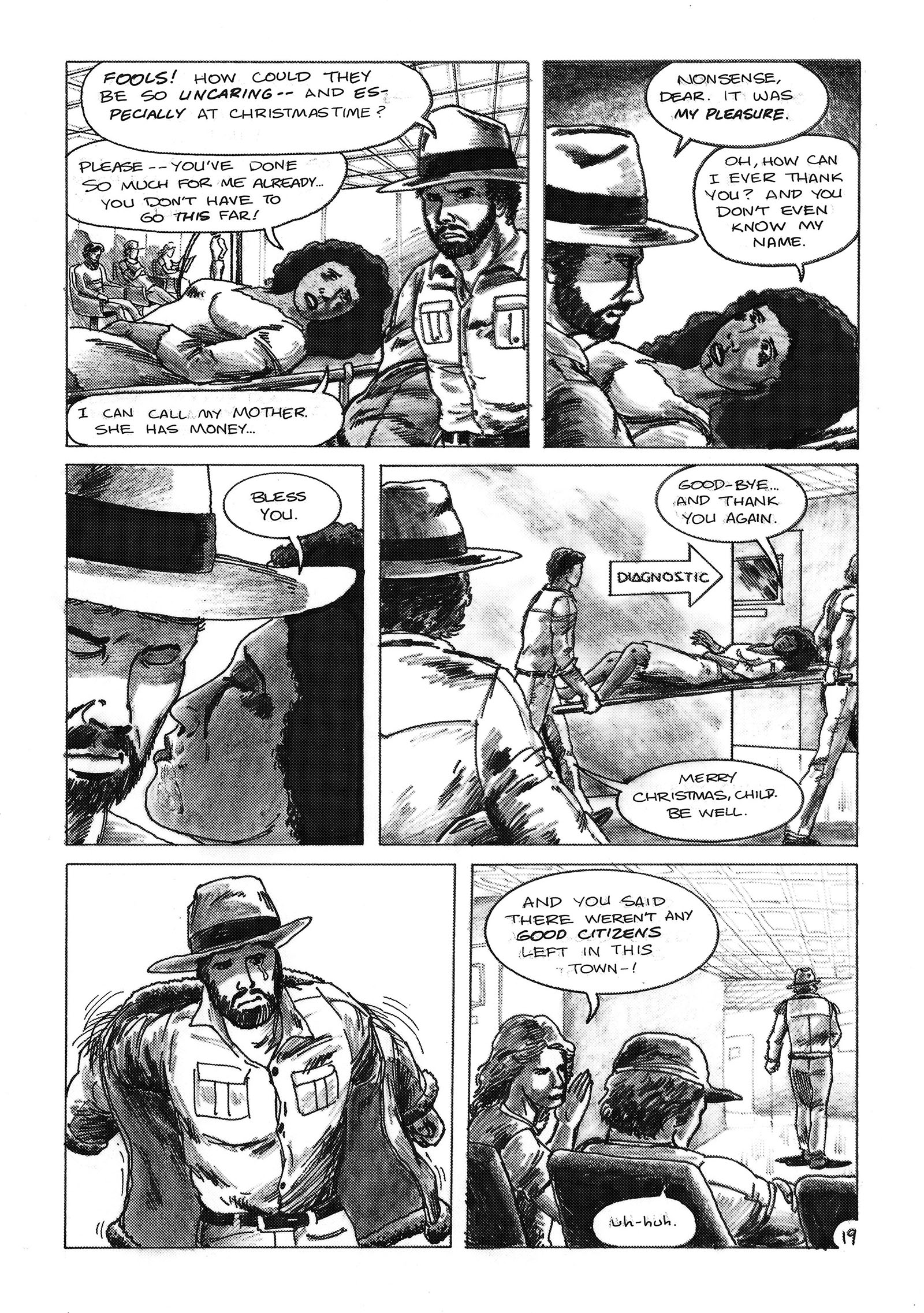

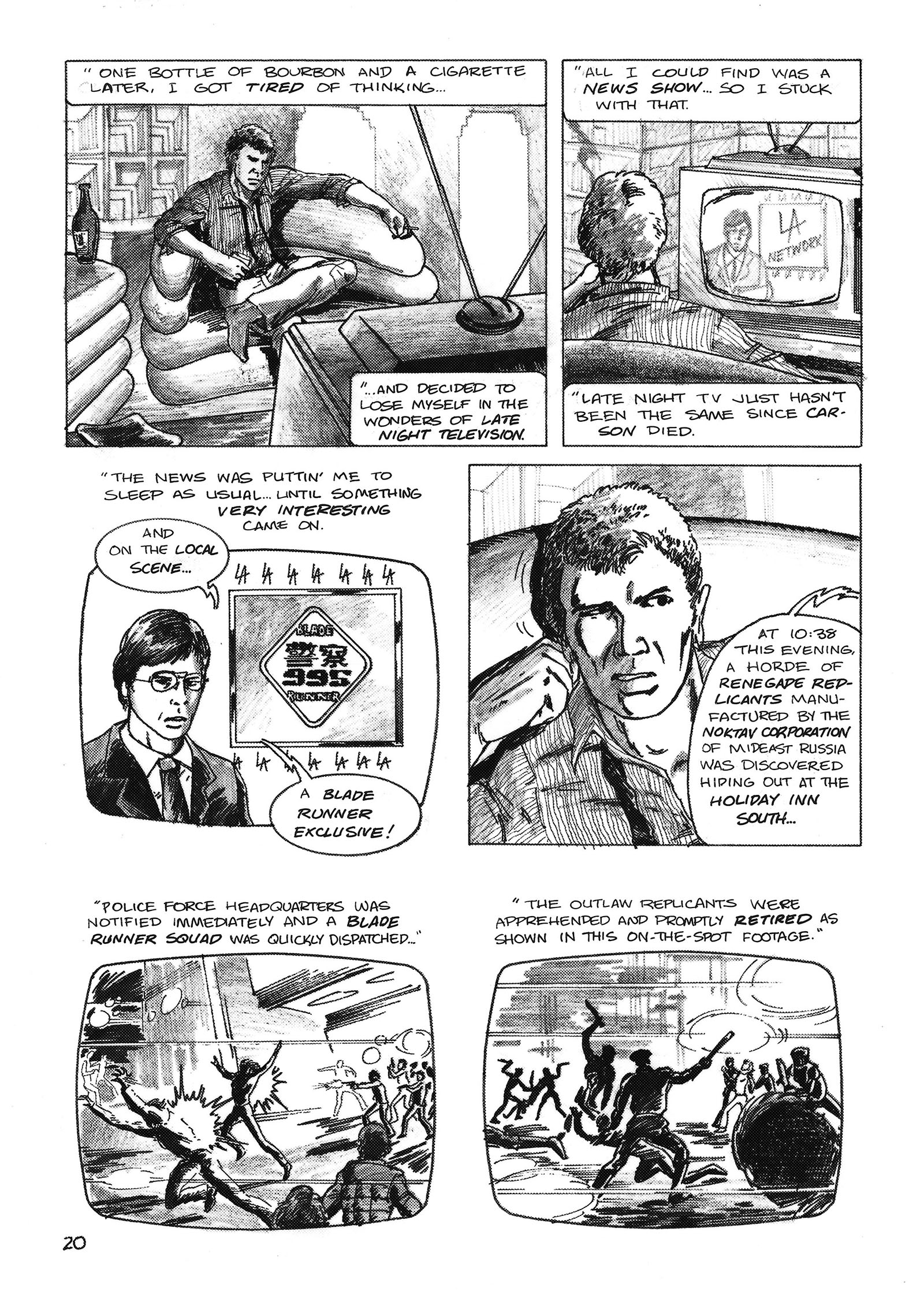

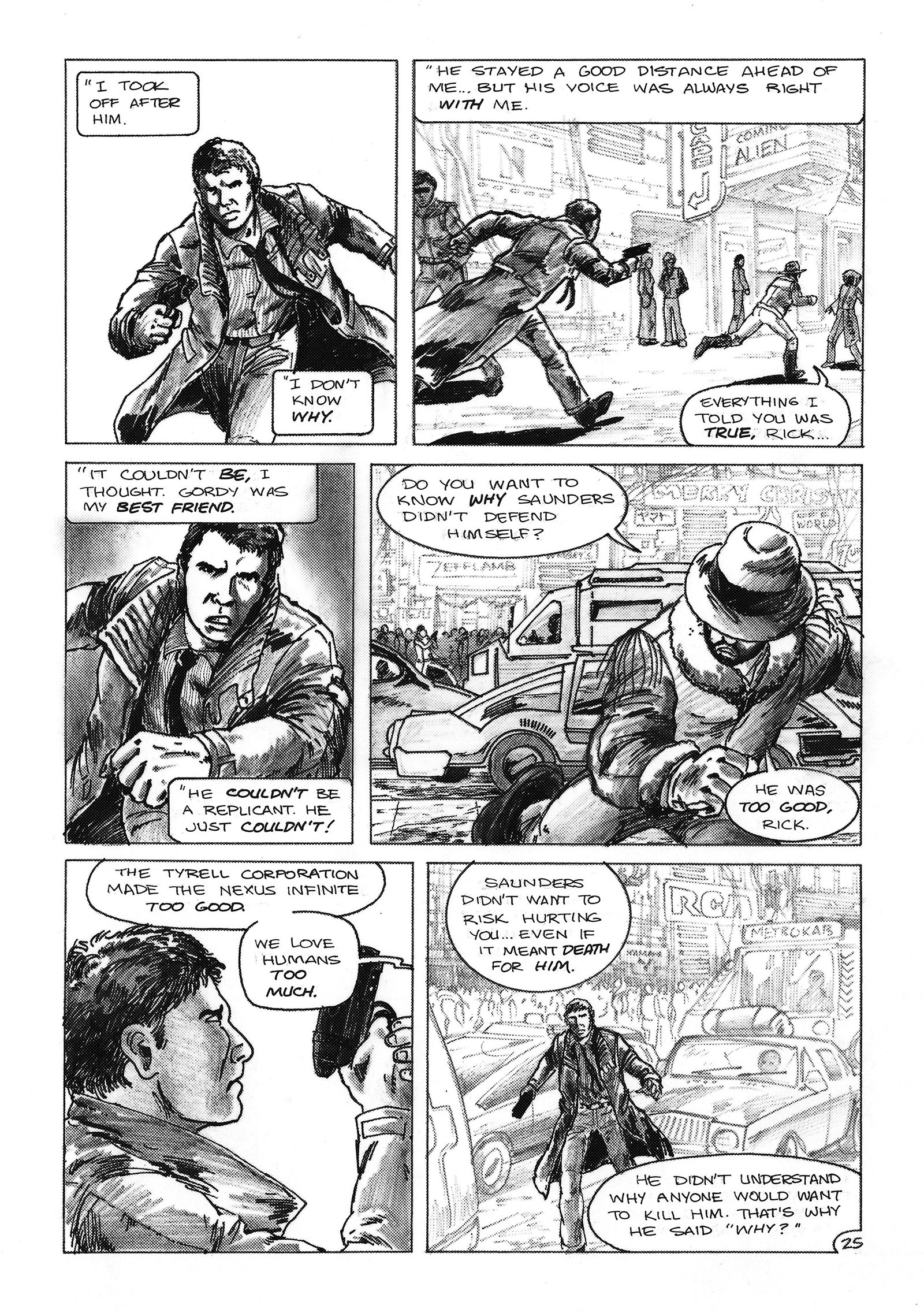

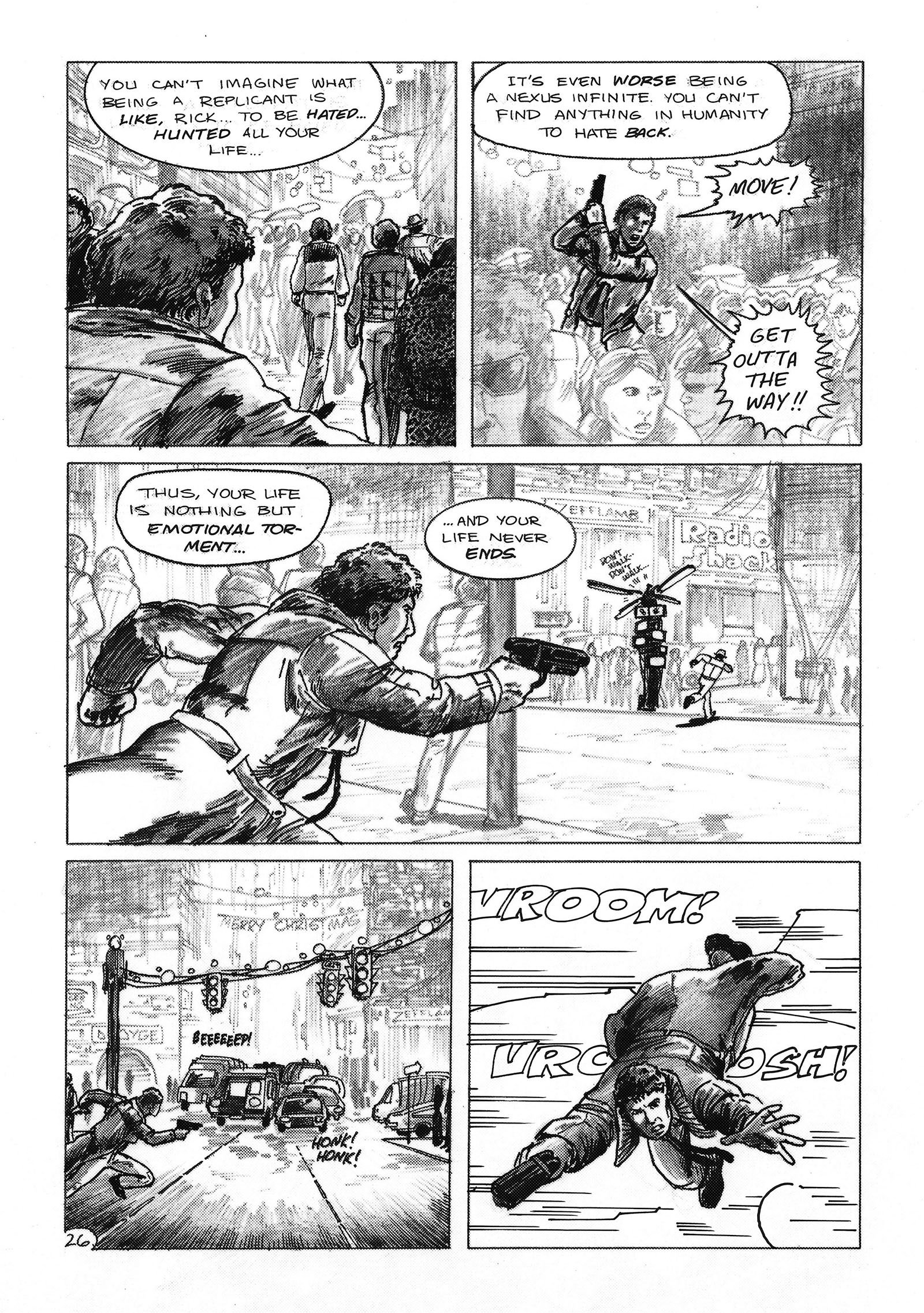

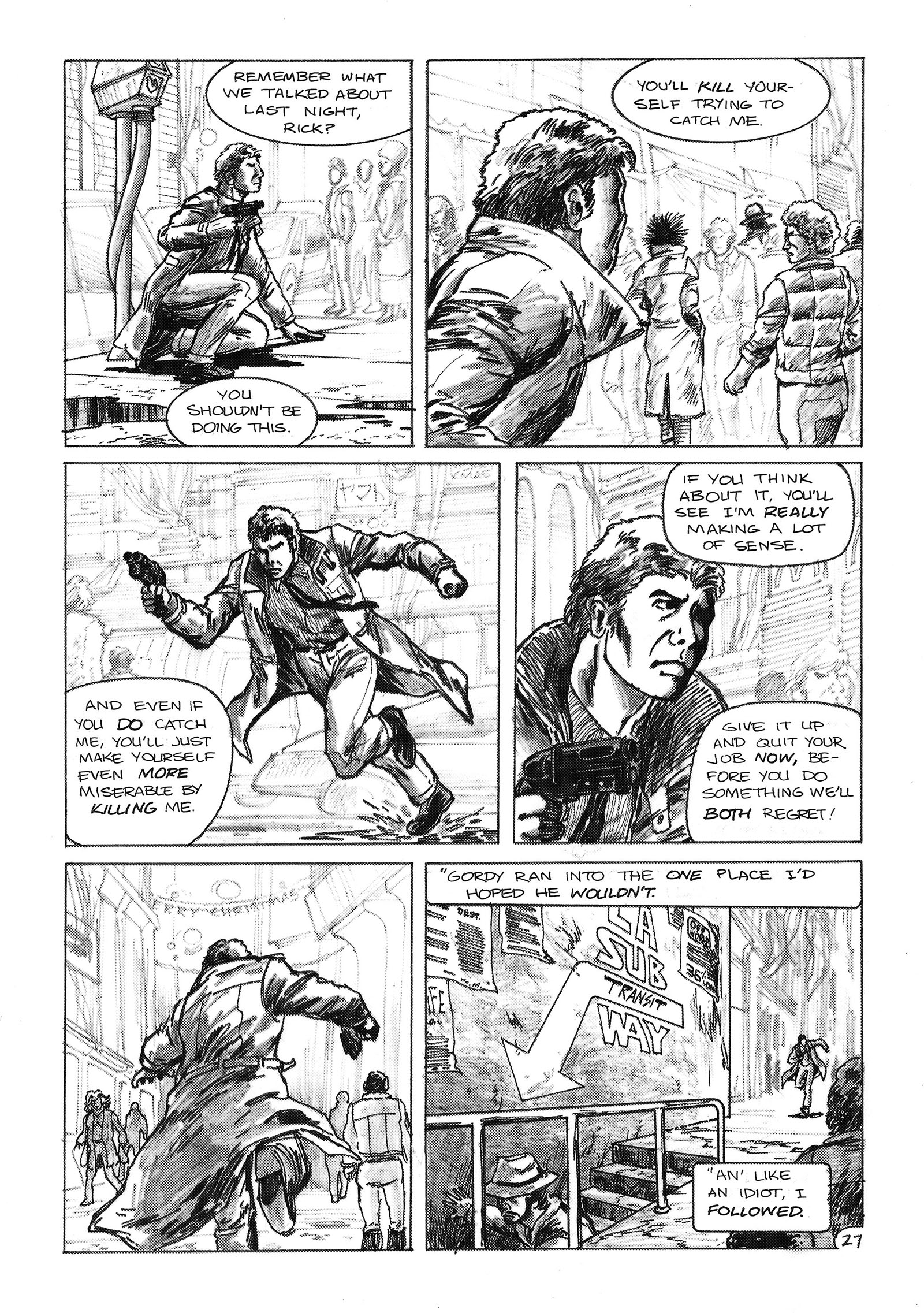

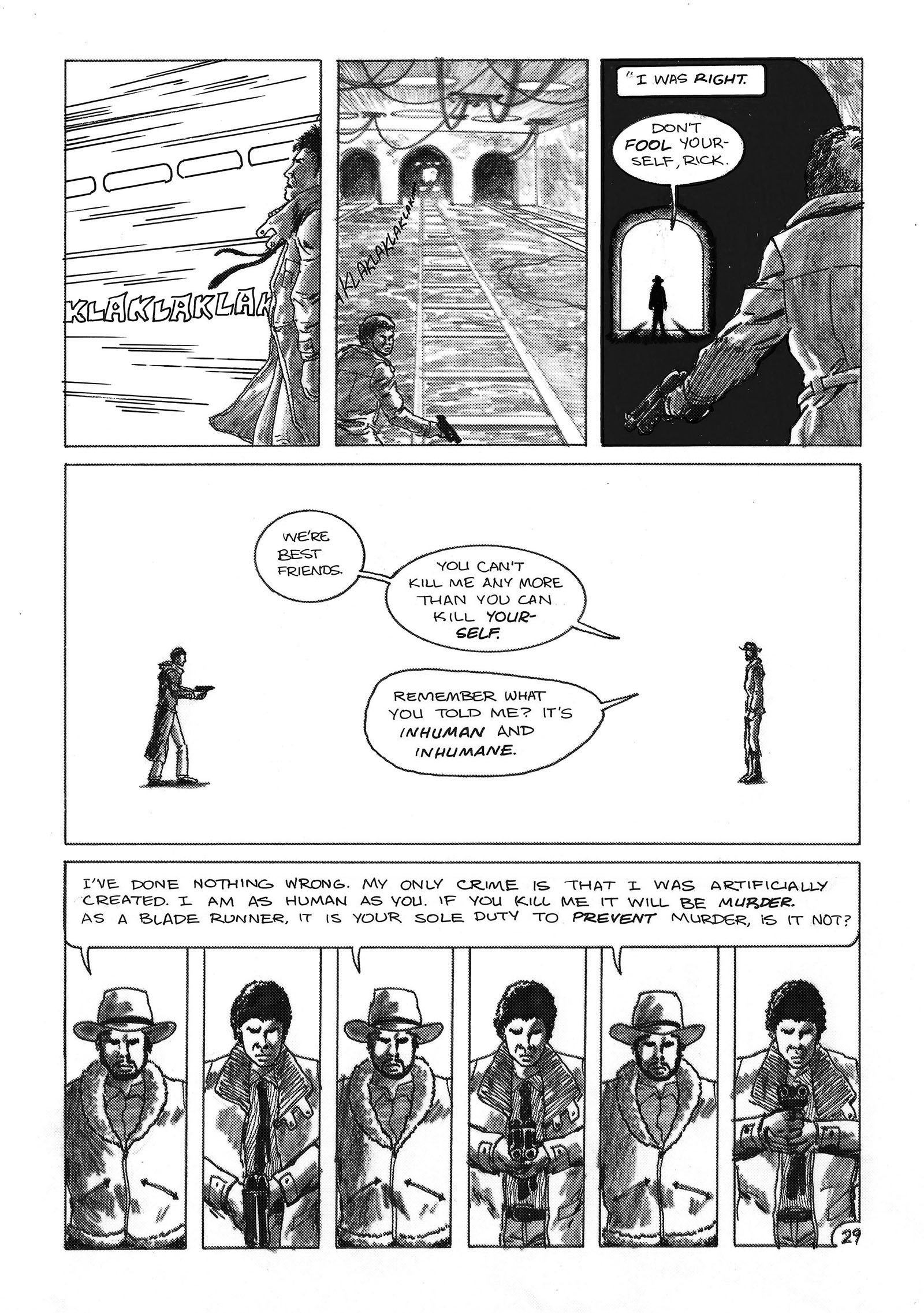

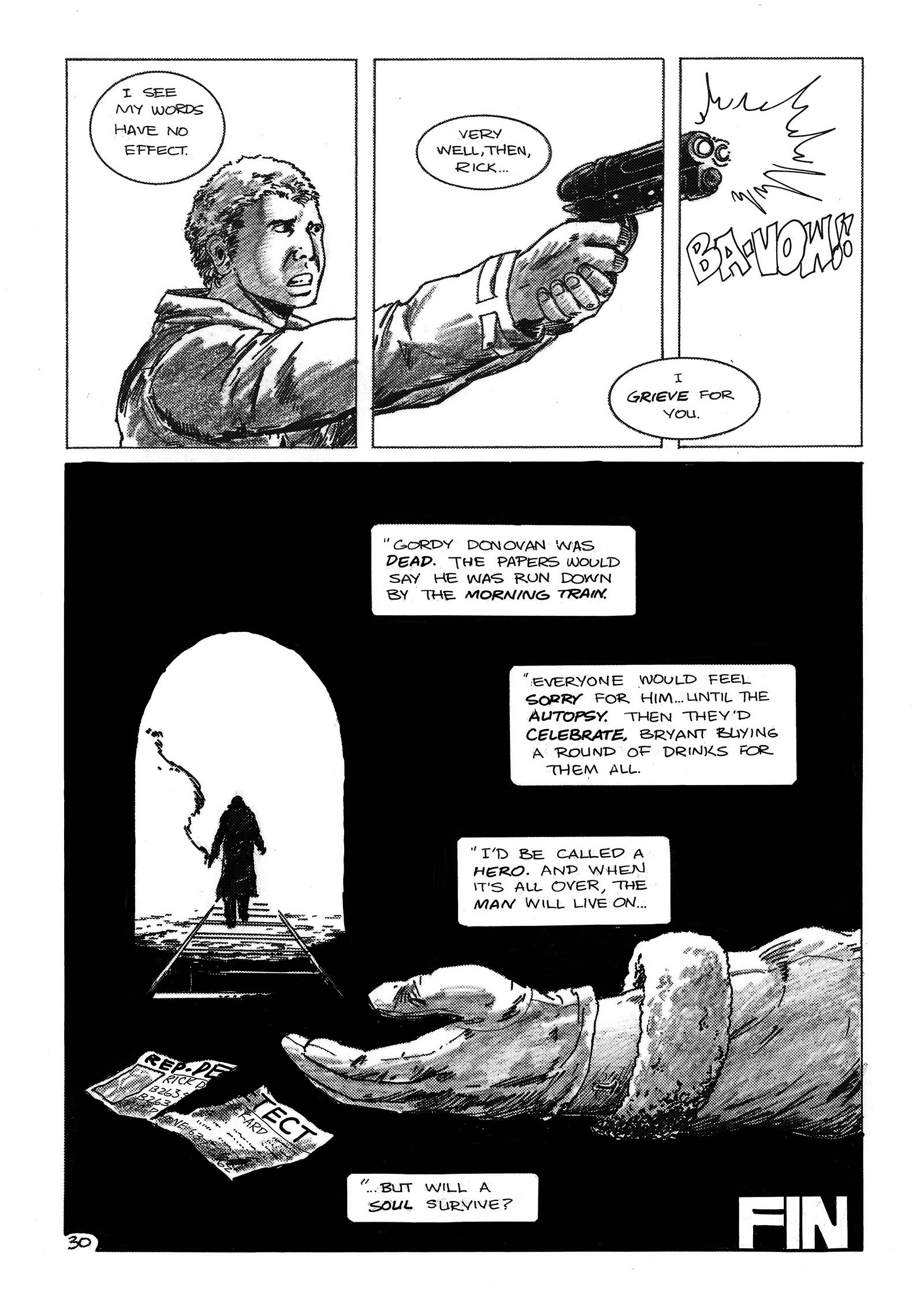

The story I came up with was suggested by the movie itself: what moved Rick Deckard to quit the Blade Runner unit before Bryant drafted him back into service? It had to be something gut-wrenching. So I came up with a prequel to explain it, set about year earlier.

In creating that story, I learned a valuable writing lesson. This was about human beings (and Replicants) on solid ground, not hurtling through space. I couldn’t fall back on spaceships, gunfights, or lightsabers. When I got to the end of the story (in penciled form), I realized that it needed a middle act to function.

We meet Deckard’s friend Gordy in the first act, then follow Deckard through an existential crisis until we meet Gordy again for a revelation in the last act. Gordy was the most important character, but had almost no presence. To fix this, I needed to break away from Deckard and follow Gordy for a while. Thus, pages 13-19 were written after everything else and plugged in to fill the hole. The lesson: if you want a reader to care about a character, give them a reason that doesn’t fall back on spaceships, gunfights, or lightsabers.

I offered the finished story to a Blade Runner fanzine called Cityspeak, and they loved it, but their publishing plans sort of fizzled out in 1983. Instead, it sat on the shelf until it could appear in the 5th issue of ‘Noids ‘n’ Droids, which came out in May 1984. And it didn’t look great. Budget printing turned it into mud. So it went back into my files and I moved on.

When I pulled all the pages out again for this article, I found ways of enhancing the art in Photoshop to finally achieve what I was going for 40 years ago. I can truthfully say this is the best it has ever looked, and it restores some faith in my 17-year-old self. That kid was on his way to better places.