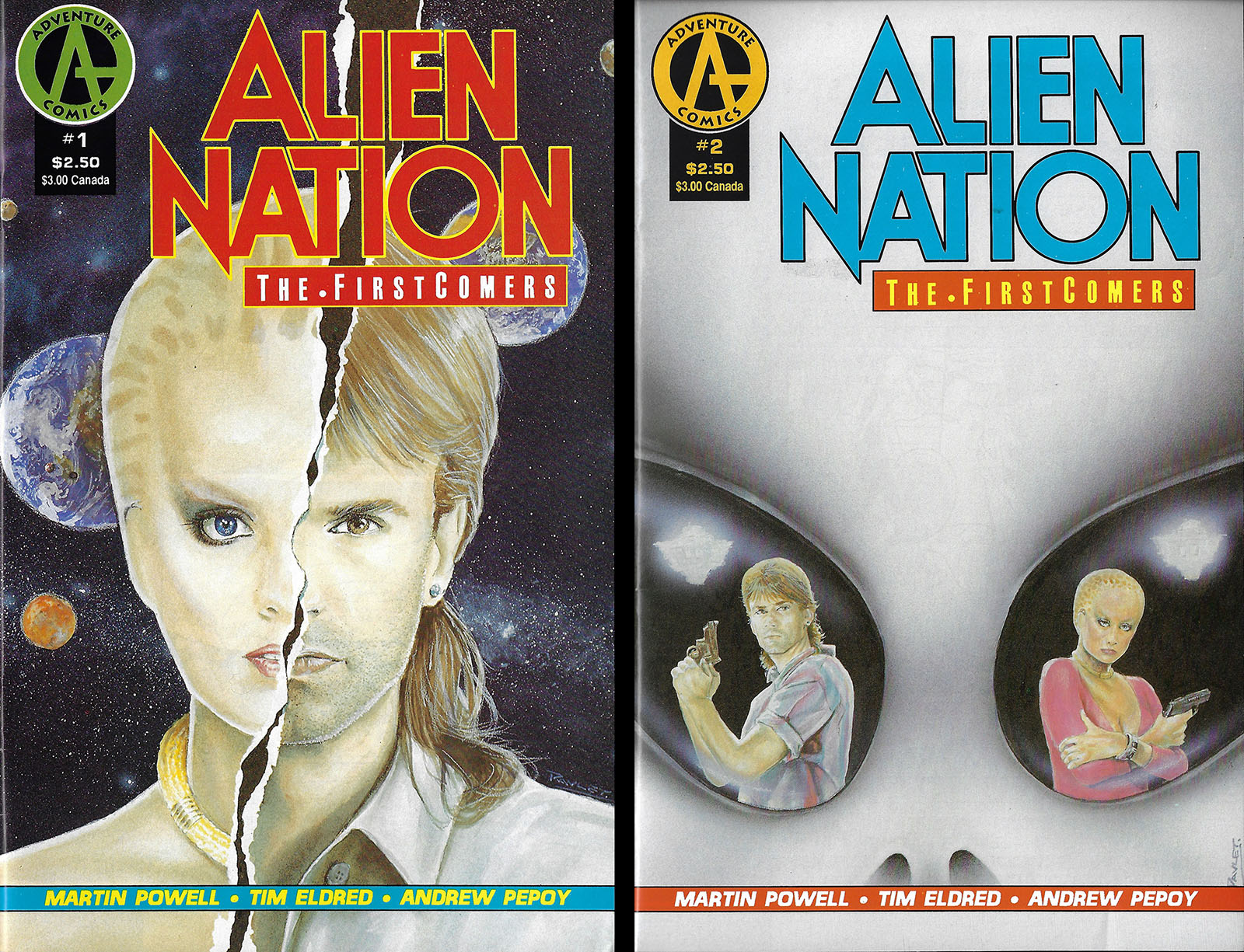

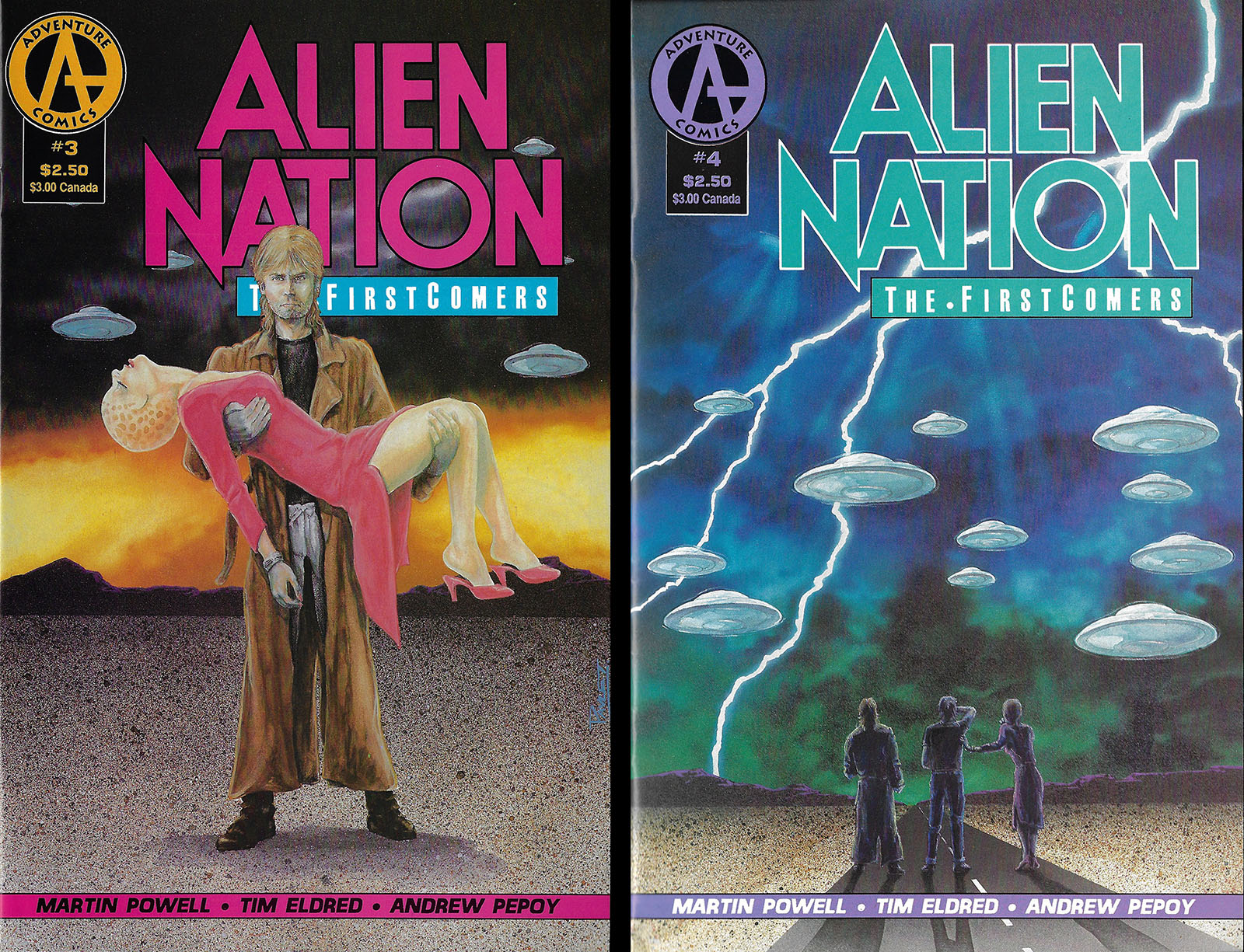

Alien Nation: Firstcomers, 1991

Most days, I forget that I spent a few months of my life drawing a 4-issue Alien Nation miniseries for Adventure Comics, an imprint of Malibu (which also published Eternity comics). I also tend to forget the Alien Nation movie and TV series that I watched back then. It was based on a 1988 movie, and lasted for one season from fall 1989 to spring 1990. It was yet another angle on a cop show, this time with human and alien cop partners. (More info here.)

That’s just how it is with some entertainment IP; it matters to you while it’s current, then it gets replaced by something else and fades into the background. In fact, before I dug into my archive, I completely forgot about this project. So I can’t blame the rest of the world for doing the same.

Malibu pumped out 7 miniseries between summer 1990 and 1992, one of which was a crazy crossover with Planet of the Apes called Ape Nation. Putting me on one of these minis was an attempt to get me drawing something that was going to make a profit. Owing to production lag time, the show had been canceled before any comic books appeared. So…another typical day at Malibu Comics.

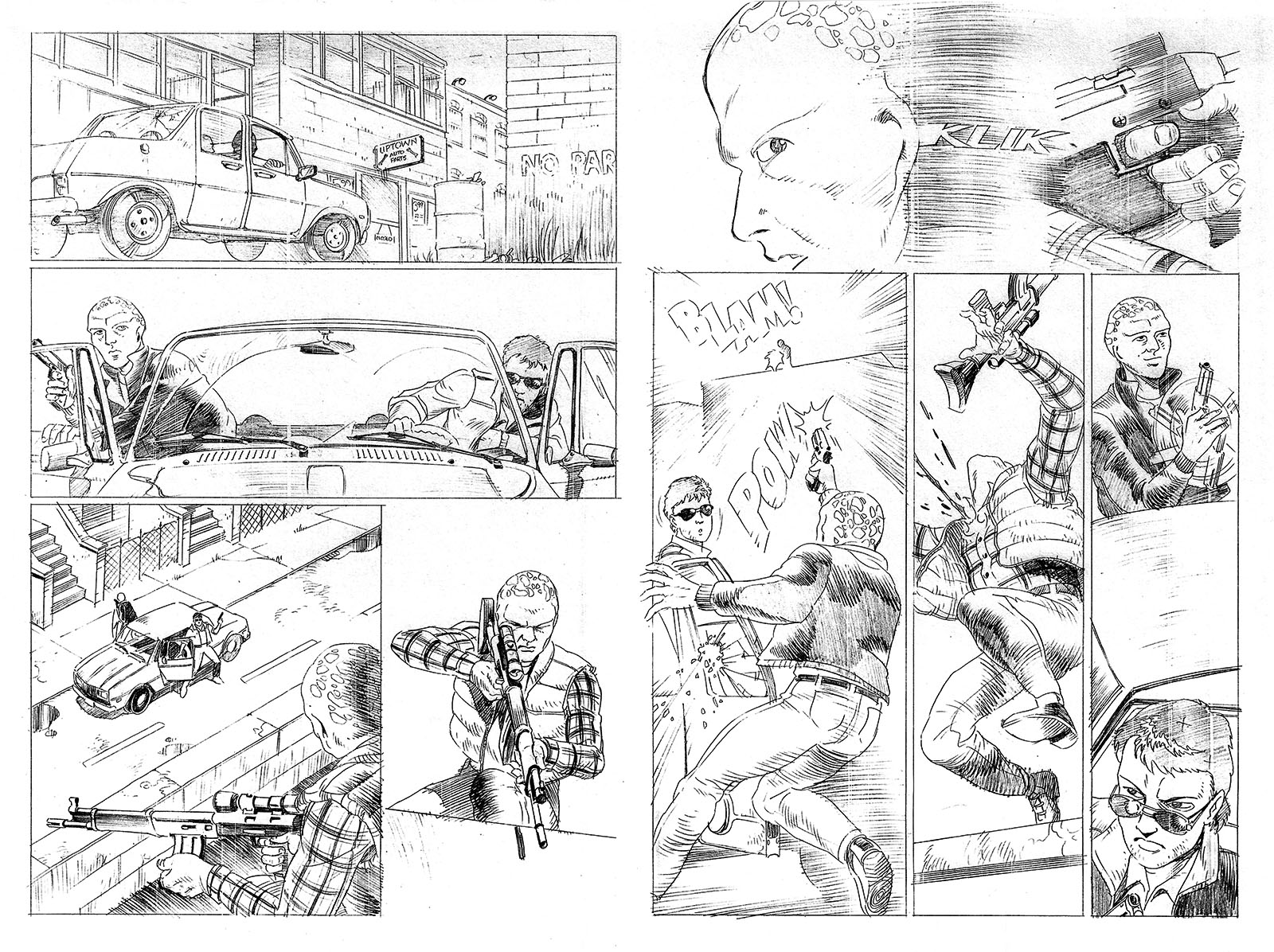

My first hurdle was to demonstrate that after a year of drawing nothing but sci-fi, I could actually render real-world objects convincingly. I passed that test in July 1990 with this 2-page sample. The main characters in the TV show were cops, and I didn’t know if we’d follow the same characters in the comic, so I drew stand-ins for them without worrying about capturing their likenesses. The editor was convinced, so I got the gig just in time to fill a slot in my schedule. I drew all four issues in fall 1990, concurrent with Emeraldas.

Every project you undertake has something new to teach you. With this one, it was the “Marvel method.” Stan Lee developed a unique system of writing comics where he would talk through the plot with an artist and describe what would happen in general terms. The artist would then draw it, deciding what needed to be seen in each panel to advance the story. When the art was turned in, Stan (or whoever) would then write a script for it, taking his cues from the pictures and any suggestions the artist came up with along the way.

That approach has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that the artist can start earlier, add their own ideas to the story, and maybe give the writer more to work with. The disadvantage is that an inexperienced artist may not know how to land all the right images to tell the story. Then the writer has to come up with workarounds, making their job harder. (Which may explain why so many Marvel comics I grew up on were SOOOOOO talky.)

Up to this point, I had only been given full scripts to work with, or created my own. So when the first “script” arrived from writer Martin Powell, and it was a description instead, that’s when I found out I’d be using the “Marvel method” on this title. Not quite what I was prepared for.

Fortunately, I had gained enough experience by then to figure it out. In fact, I found it liberating. Working without specific dialogue got me thinking more about the flow of pictures. Martin gave me just enough information to decide what should be communicated on each page, then I decided out how to break up that information into individual panels.

In fact, I discovered a few years later that it was akin to animation storyboarding. You get a script with dialogue in it, but the rest is just description in text form. You apply your storytelling and filmmaking instincts to decide which specific shots are needed. I first learned how to do that with this miniseries. I’m still of the opinion that you get a stronger end product if you start with a complete script, but there are always different ways of doing things.

On the other hand, when I look back at these comics, the deficits in my art are glaringly obvious. Backgrounds and props and compositions are okay, but the figure drawing is pretty awful. Heads were generally too big and faces were never quite “there.” Usually, your perception is in lockstep with your ability, so you’re unable to recognize your own flaws. But once in a while, I managed to render a body or a face that broke away from my bad habits, and I understood that something had improved. So that was encouraging.

After I finished, Martin Powell did the actual scripting based on what I drew. I offered some dialogue suggestions that occurred to me along the way (I had to imagine what they were saying, of course), and he took it from there. I didn’t actually know what he’d written until the finished comic arrived with all the lettering and inking in place. (Ditto with the cover art by Terry Pavlet.) It was gratifying to see my suggestions incorporated into the end product.

Another gratifying thing was that I got a friend on board, a fellow Michigander named Andrew Pepoy. We met in the life-changing “comic book production” classes given by local pro Mike Gustovich, and we both had similar ambitions. I made it to pro-ville before Andrew did, and when my editor at Malibu asked for inking candidates, I gave him Andrew’s name. Next thing I knew, he was hired. I’m pretty sure it was his first professional comic book work, and he’s been in the biz ever since. (Visit his website here.) Like me, Andrew probably looks back at this miniseries like a cringey high school yearbook. But we’re cut from the same Michigan cloth, so I’m certain that he knows the value of humility.

Here are all four issues from cover to cover. Enjoy.