Comics go to the movies: Outland (1981)

You might have heard that the members of Generation X (born in the 60s and 70s) experienced a LOT of changes in the world of entertainment media. Speaking as someone born on the leading edge (1965), I can personally attest that the changes were vast. I’ve been a consumer of books, comics, animation, TV, and film for as long as I can remember, and the media world we’re in now has evolved to closely match the one I wished for. And of course, it came with unforeseen consequences.

As a teenager from ’77 to ’85, I feel like I was perfectly aligned to absorb all the things I was supposed to see in all my favorite media. I watched techniques, expertise, and technology grow year by year. There was always a breakthrough just around the corner to build upon the previous one. This was true in every medium I followed. New tools and methods for telling stories were in constant development, and the ever-expanding field of media merchandising gave everyone something to chase after.

A popular movie, for example, would often arrive with a host of support media. You could usually rely on a spinoff book, a novelization, a comic book adaptation, and a soundtrack album. When home video worked its way into the mix (starting in the early 80s), a VHS tape would follow. Back then, a movie would usually be in theaters for a few months, and a VHS would appear maybe a year later. This gave all the licensors a comfortable window for sell-through of the merch. After all, once the tape was available, demand for other versions of the film would drop.

In the time since then, of course, things have changed dramatically. The window between theater and home viewing is much shorter, so the demand for support media is much lower. Spinoff books, novelizations, and comic adaptations for today’s films are scarce if not extinct. Do we really need all that stuff? Probably not. But after experiencing what they had to offer, I feel like we’ve lost something special.

To better communicate my point, I’ll use this platform to provide a look at the gifts that were made for media hounds like me before they fell into the memory hole. And I’ll start with a movie that itself is now barely remembered: 1981’s Outland.

To be brutally honest, it wasn’t great. I should have seen it in a theater, but when it came out in May 1981 (the “golden month” for event movies hoping to lead the summer season) I wasn’t yet driving. Thank god that got sorted out before the next summer, which was one of the greatest movie years ever. But since I was still reliant on my parents in the first half of ’81, I rarely got to see anything in theaters unless they wanted to see it, too. And they had zero interest in “my” movies.

Thus, all I saw of Outland in the early days were the TV commercials, which made it feel like the next Alien. But outside the confines of a theater, spinoff merch appeared in all the usual categories. This, in itself, gives you one example of why this stuff was made; it was a way to capture those of us who (for whatever reason) couldn’t see the movie itself.

The home video took a year and a half to show up (unthinkable today), finally appearing November 1982. So, by the time I saw Outland, other movies had already surpassed it. If I’d seen it when it was fresh, I would have been more impressed. But it ended up being just OK. Nice production values, but definitely locked into the context of its time. No one should be surprised by its obscurity today.

So, why am I focusing on a not-great movie here? To demonstrate that a not-great movie could still generate something great in its wake. Let’s check off the categories.

Novelization by Alan Dean Foster

Soundtrack album (LP) by Jerry Goldsmith

Right away, two of the biggest names in the SF sphere float to the top. Alan Dean Foster was an accomplished novelist in his own right and ran the table on adapting the top films of the 70s, including Star Trek, Star Wars and Alien. Jerry Goldsmith had been scoring for film and TV since the 50s with countless credits that only kept growing until we lost him in 2004. I first heard his work on Alien.

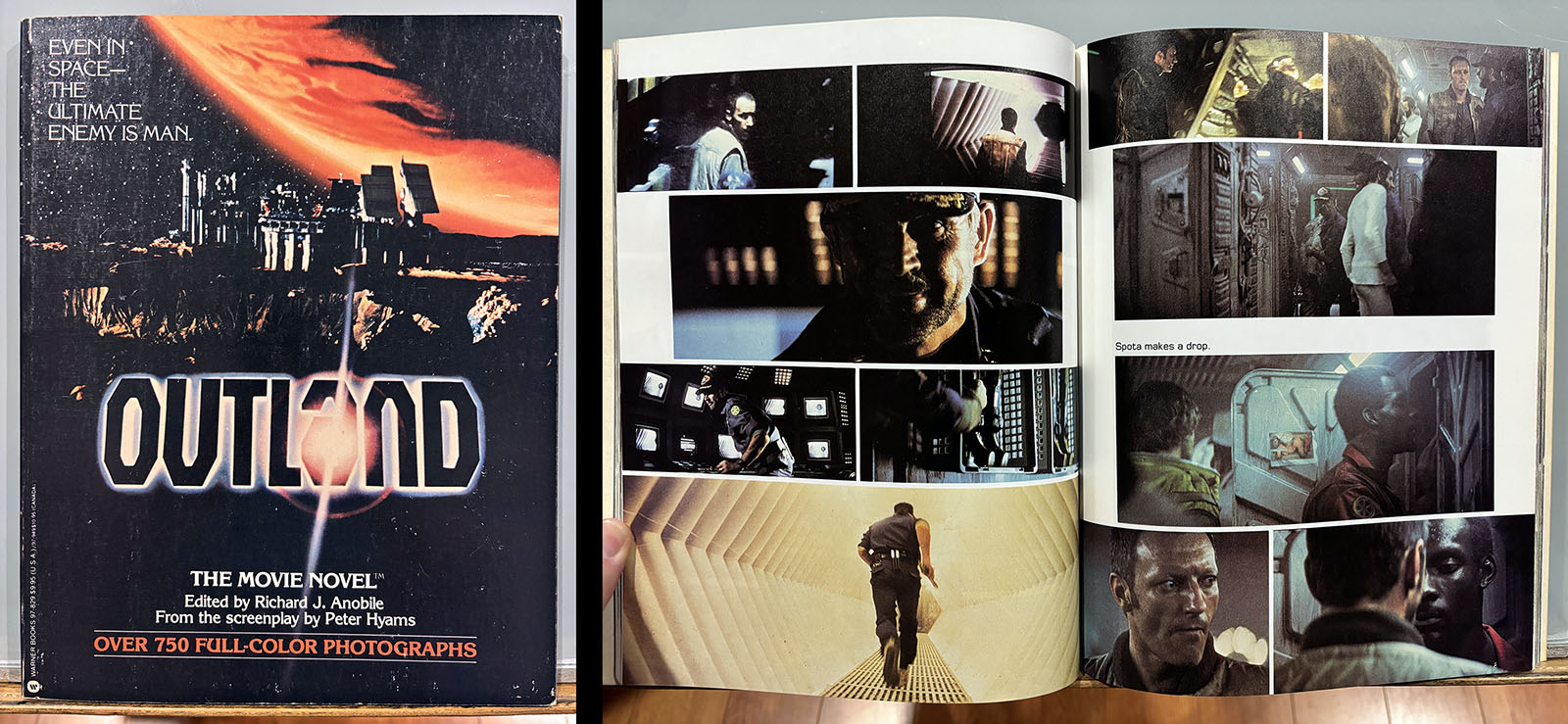

Movie Novel by Richard J. Anobile

Now we step into a rarified realm of publishing that was solid gold to me in the pre-video era. “Movie novels” were the next best thing to a film itself, a huge collection of stills used to retell the story. Filmmaker and movie book author Richard J. Anobile mastered the format with Alien and also applied it to the first two Star Trek movies, among other titles.

Others dabbled in the concept under the branding of “Fotonovels,” bringing still images to the page in a time long before you could screenshot any frame at any time. I kept waiting and praying for someone to do the same with Star Wars, which seemed like a no-brainer to me, but it never happened.

These went way beyond the standard publicity photos that were shot on a movie set by a photographer who wasn’t actually behind the movie camera. If you read movie magazines like I did, you’d see those photos over and over. But they weren’t the “real thing” the way an actual frame blowup was. Before home video, it was the closest you could get to on-demand viewing.

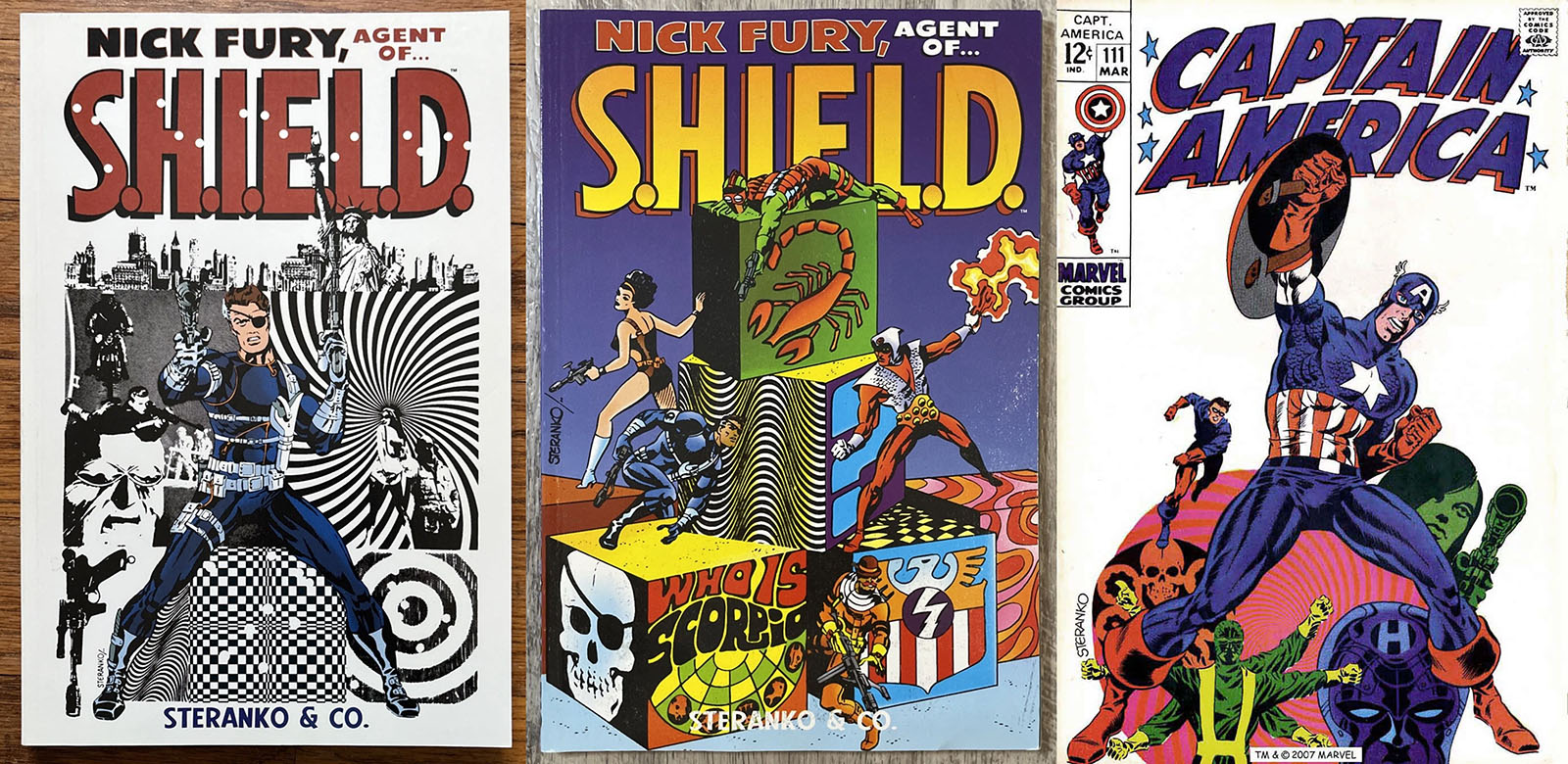

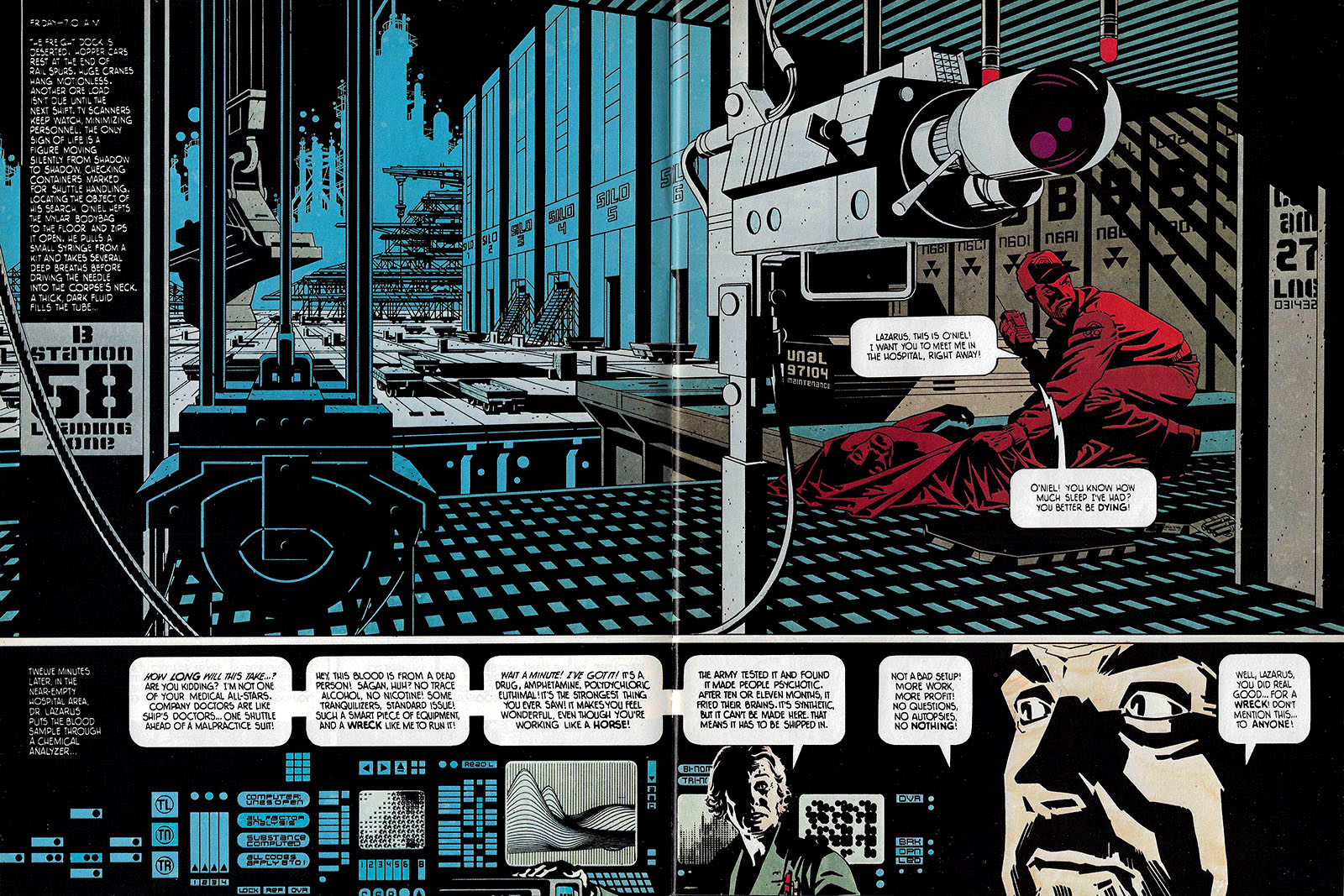

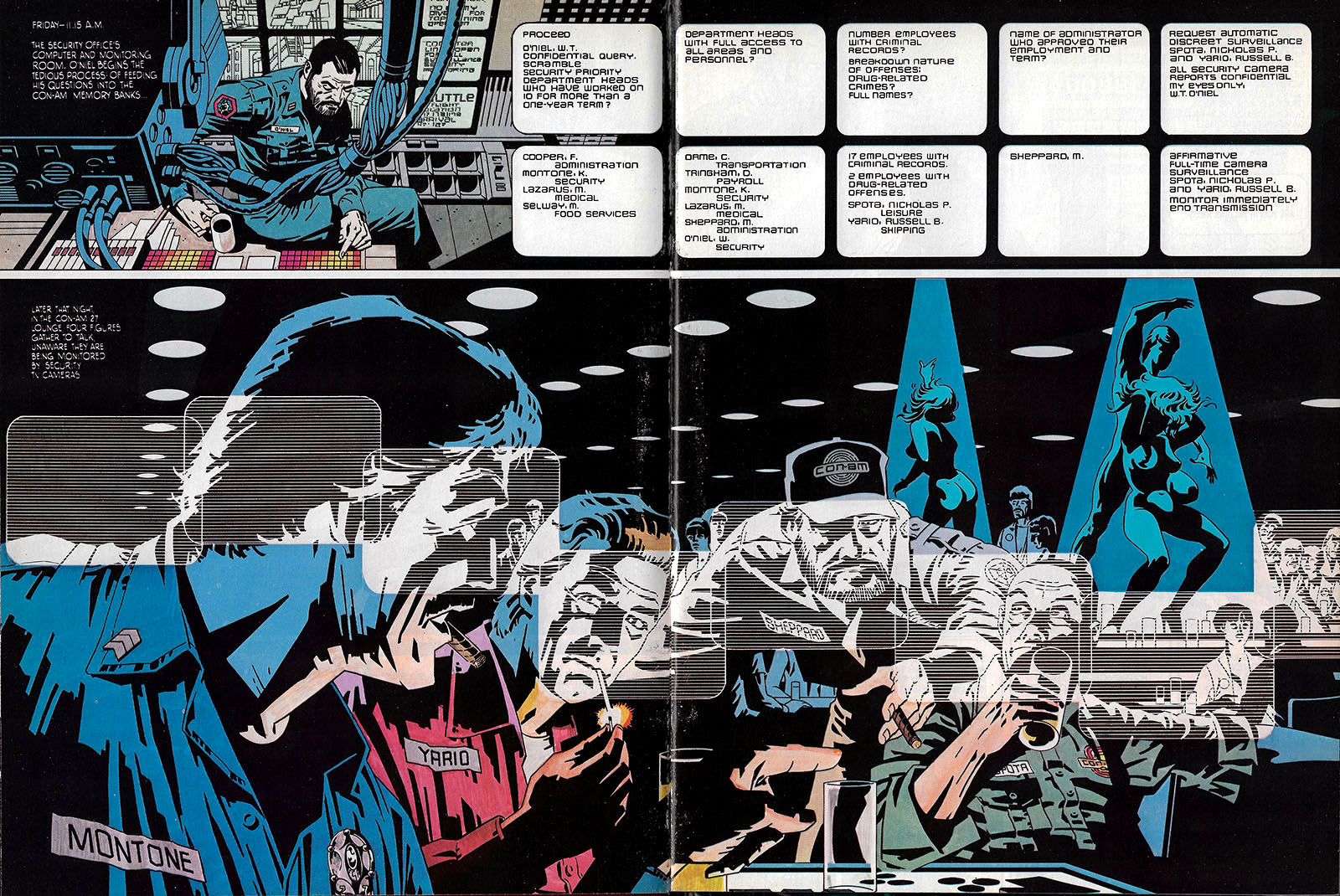

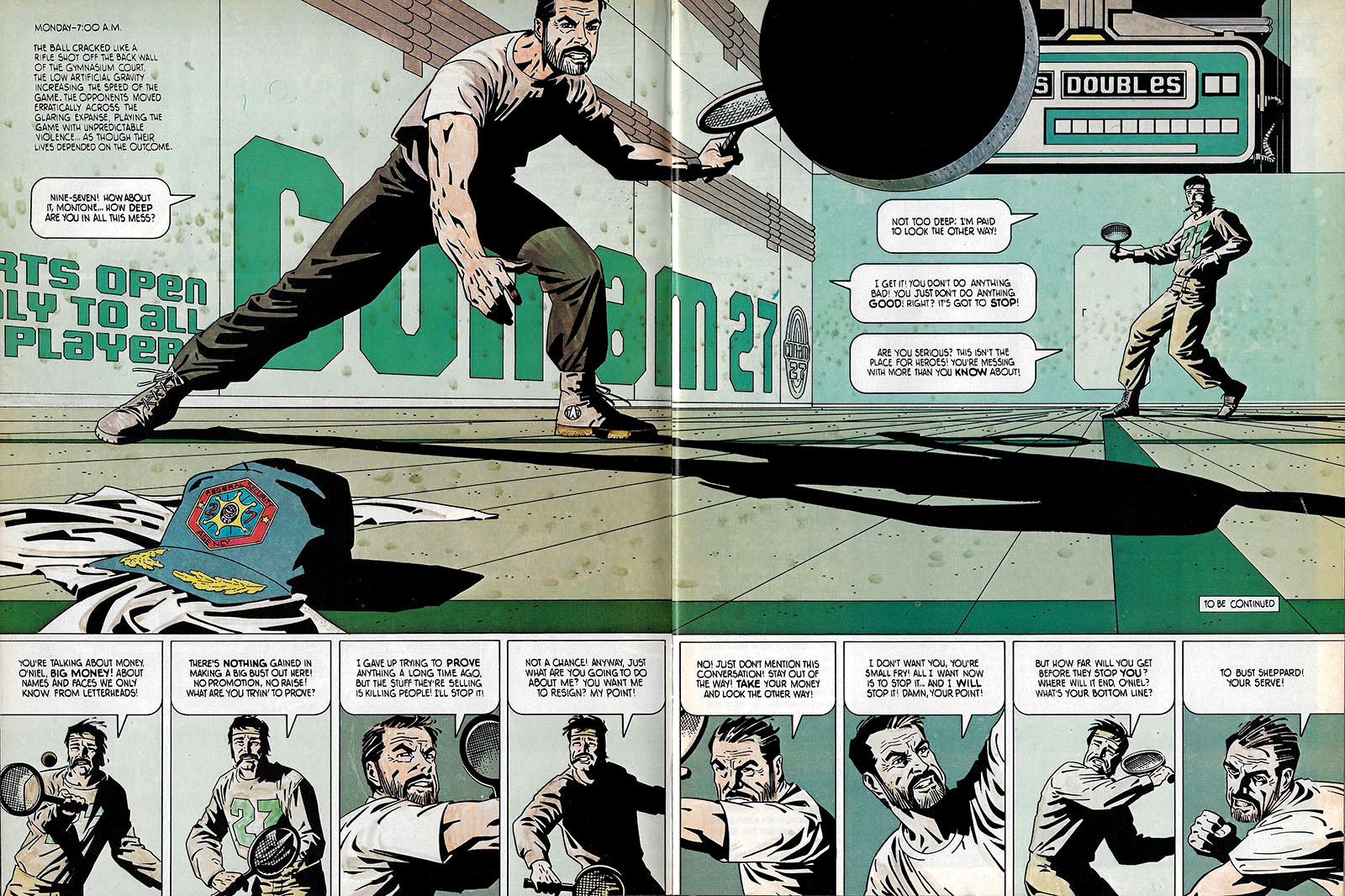

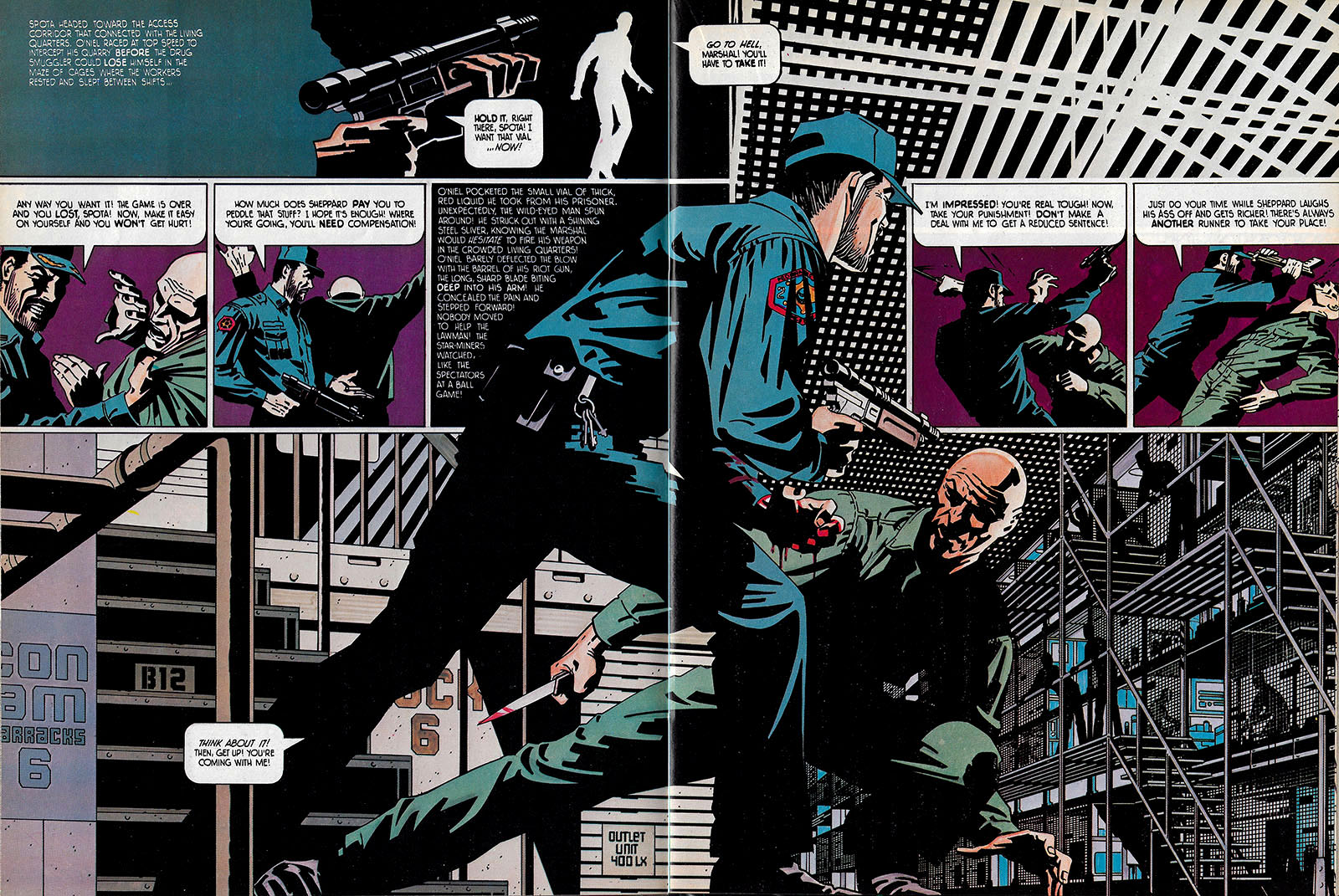

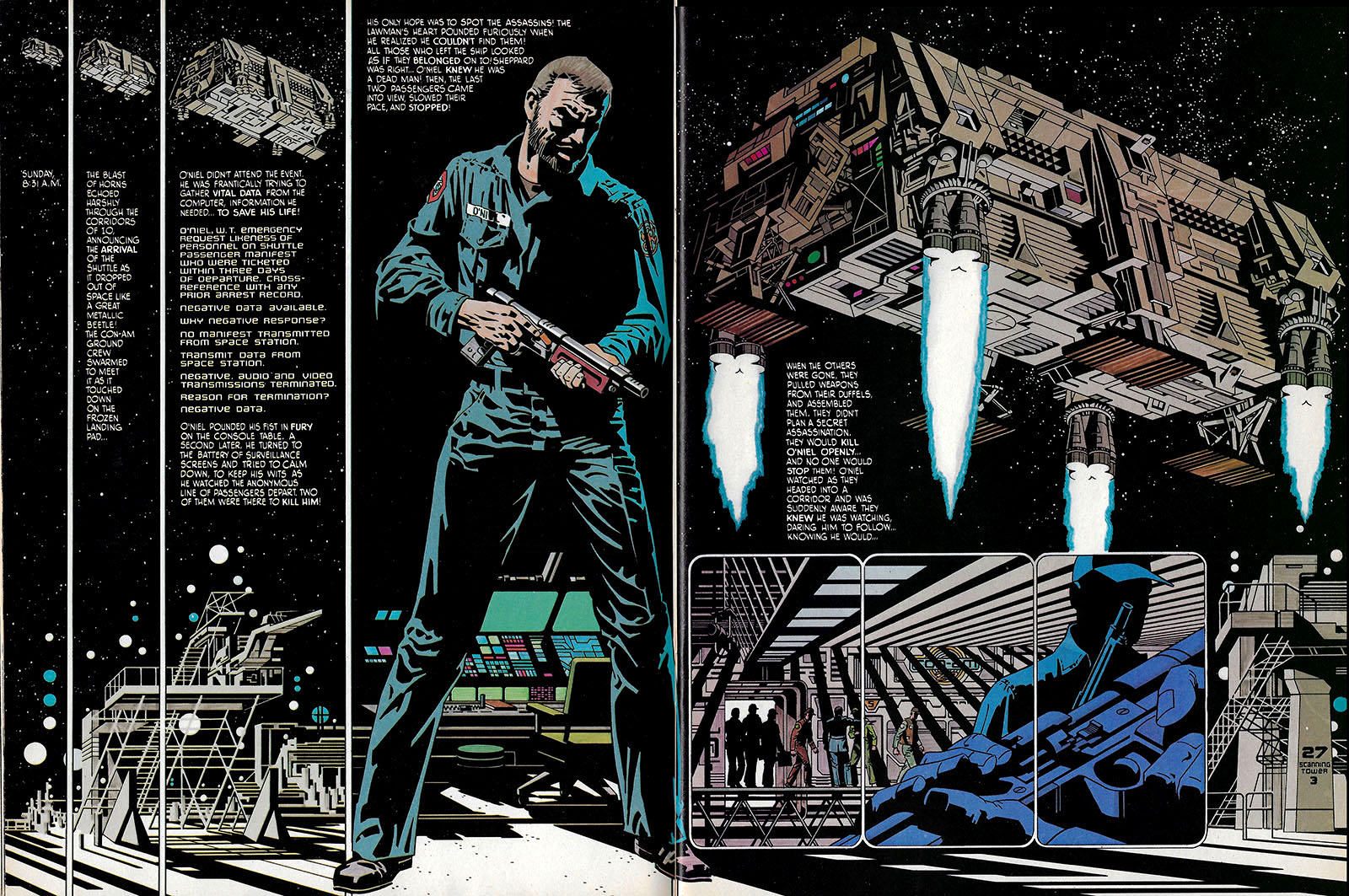

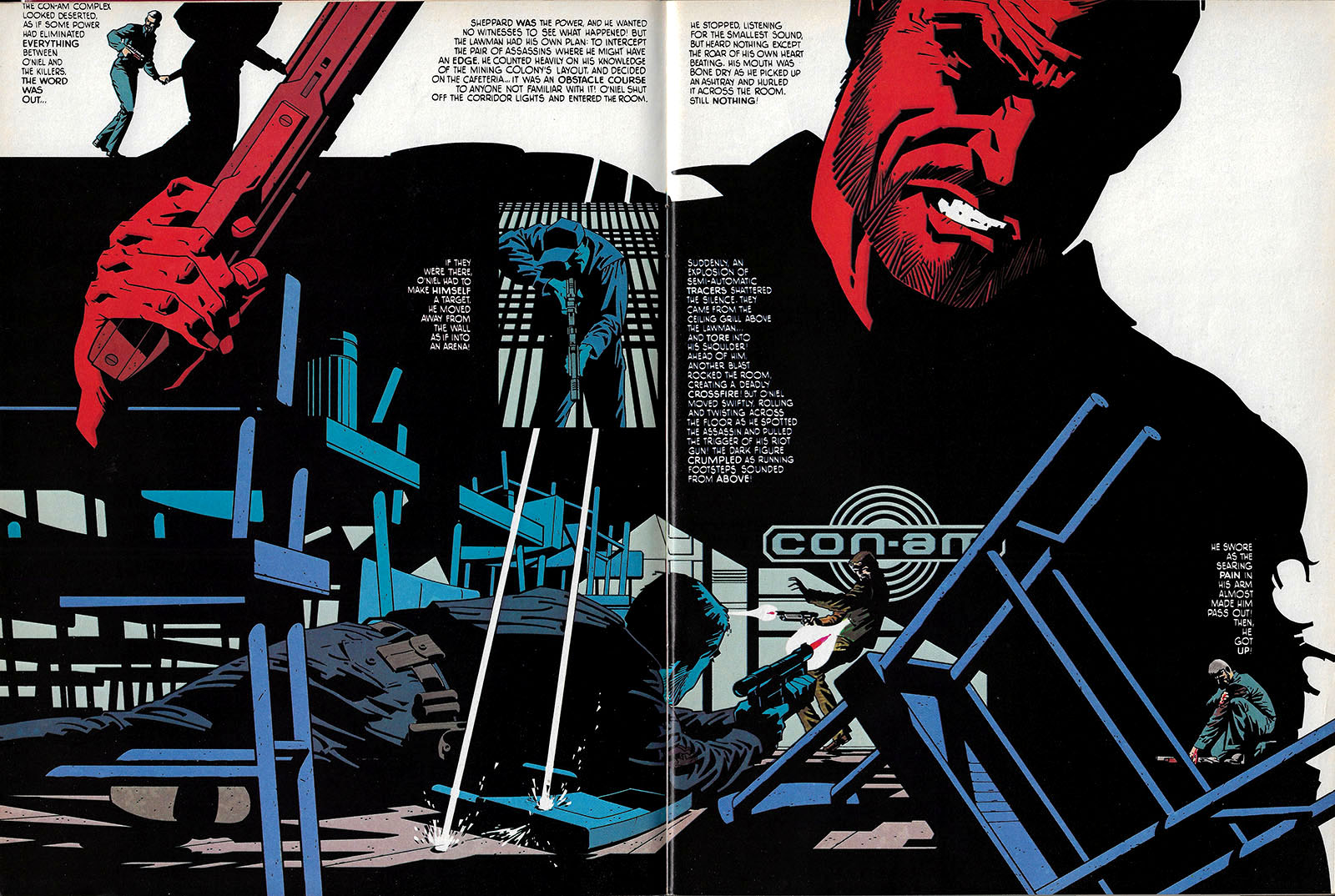

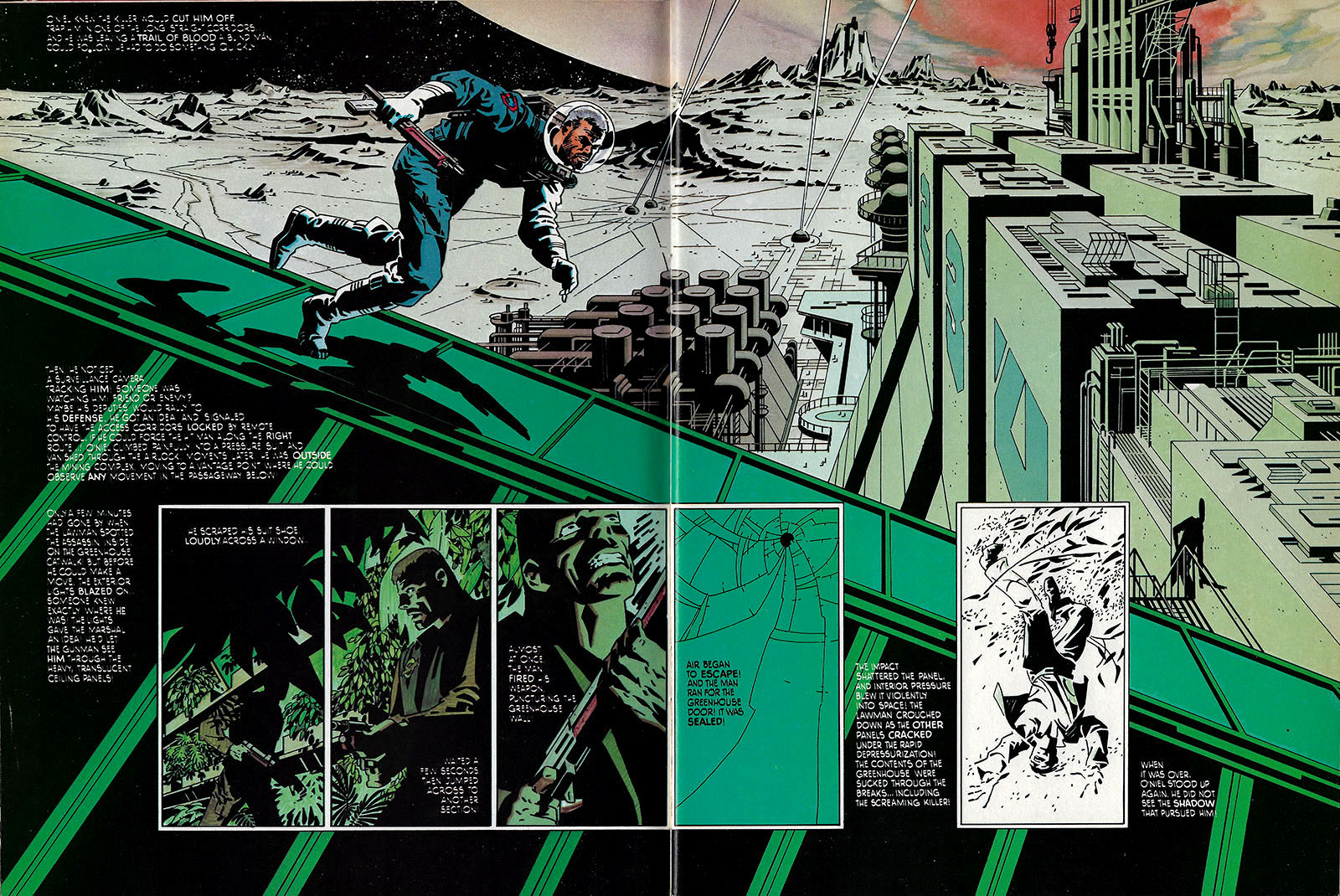

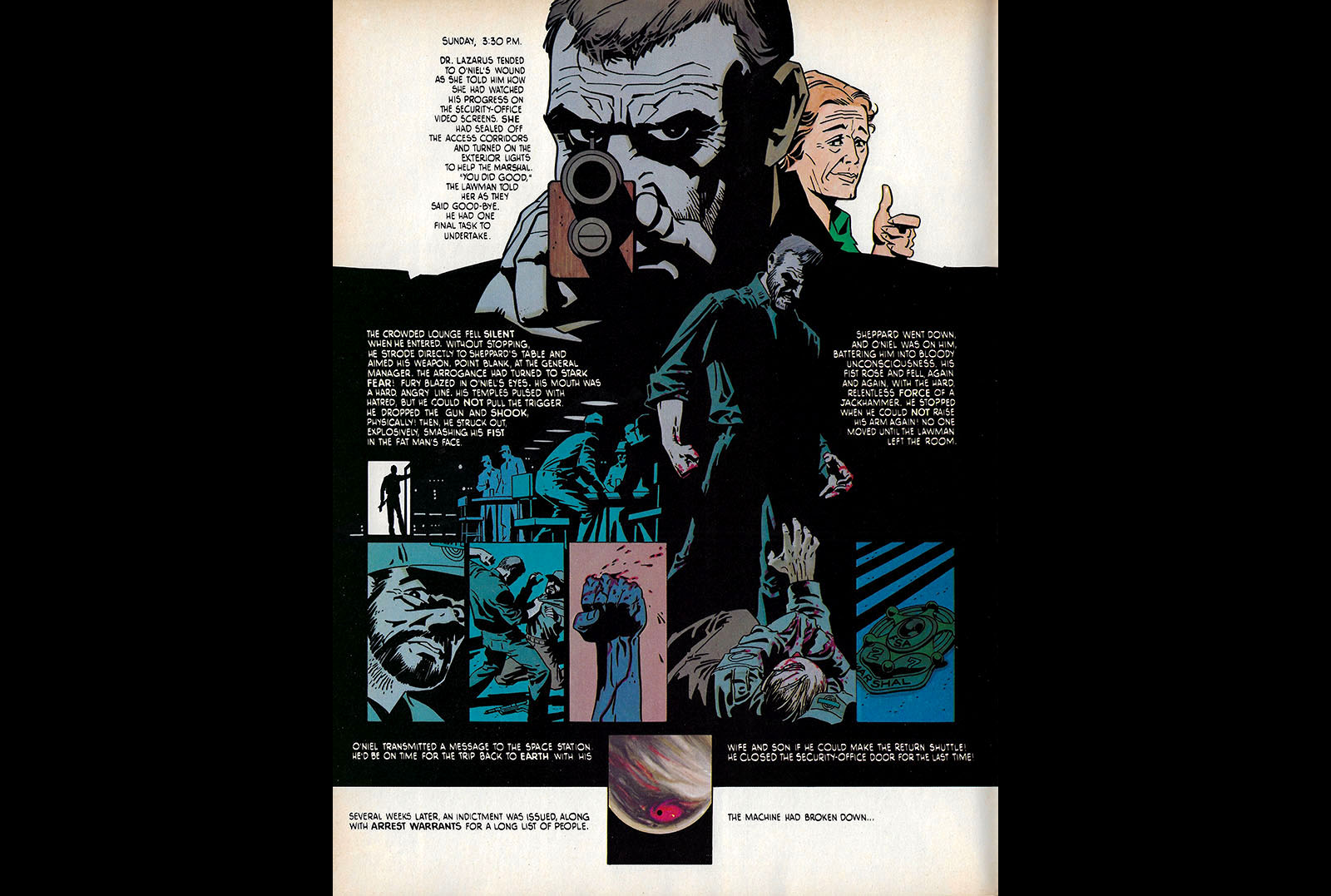

Comic adaptation by Jim Steranko

And here we are at the core reason I decided to write an article about a not-great film from 1981. It came with a truly exceptional comic. The key to this was a truly exceptional artist.

Jim Steranko single-handedly built a bridge between two worlds in the 60s and 70s: comic books and graphic design (for advertising). This informed his creative choices in a truly unique way, bringing dynamism to his ad designs and graphic experimentation to his comics. He quickly earned his stripes at Marvel with layouts that broke new ground in storytelling by making the page itself a piece of art in concert with the individual panels that told a story.

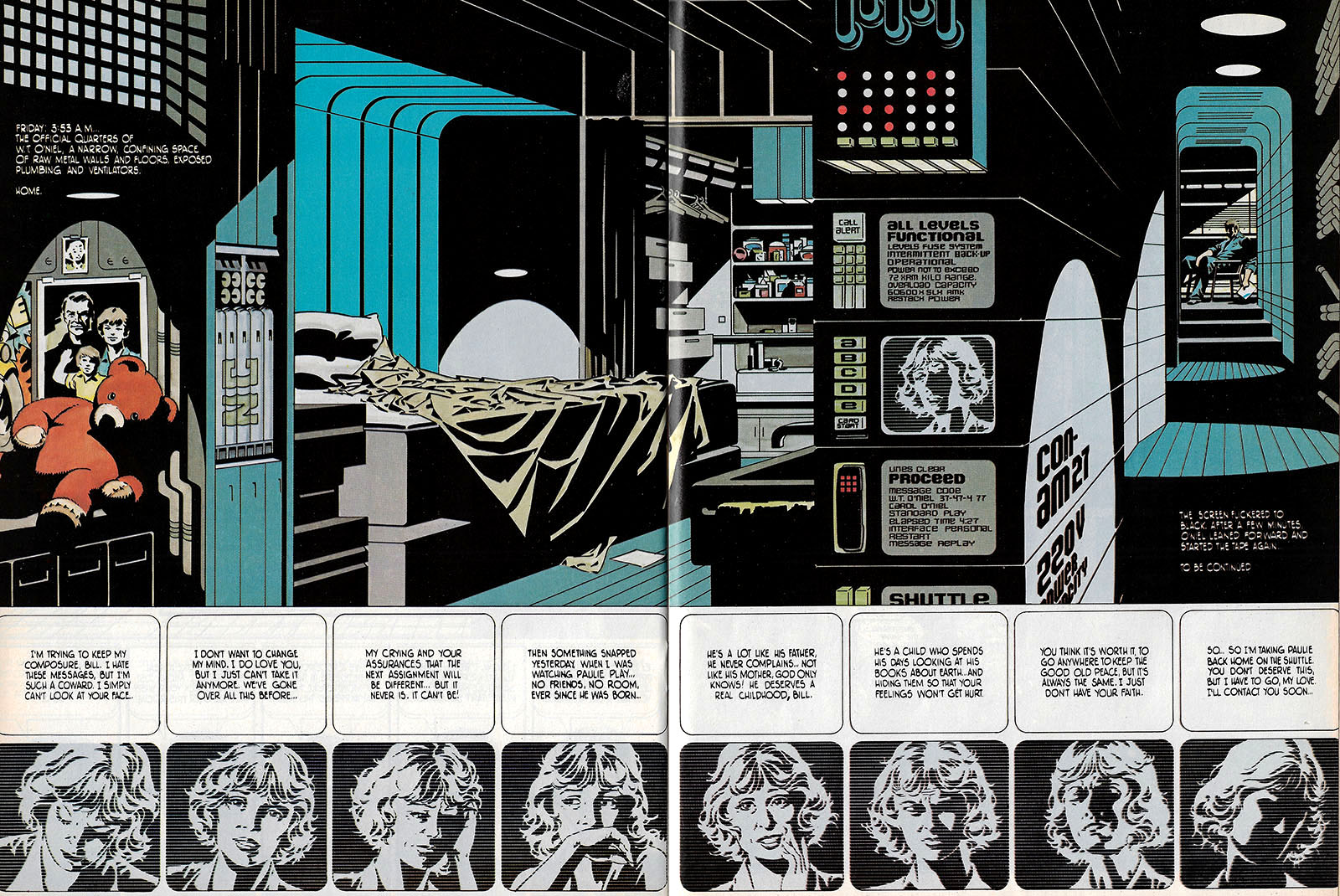

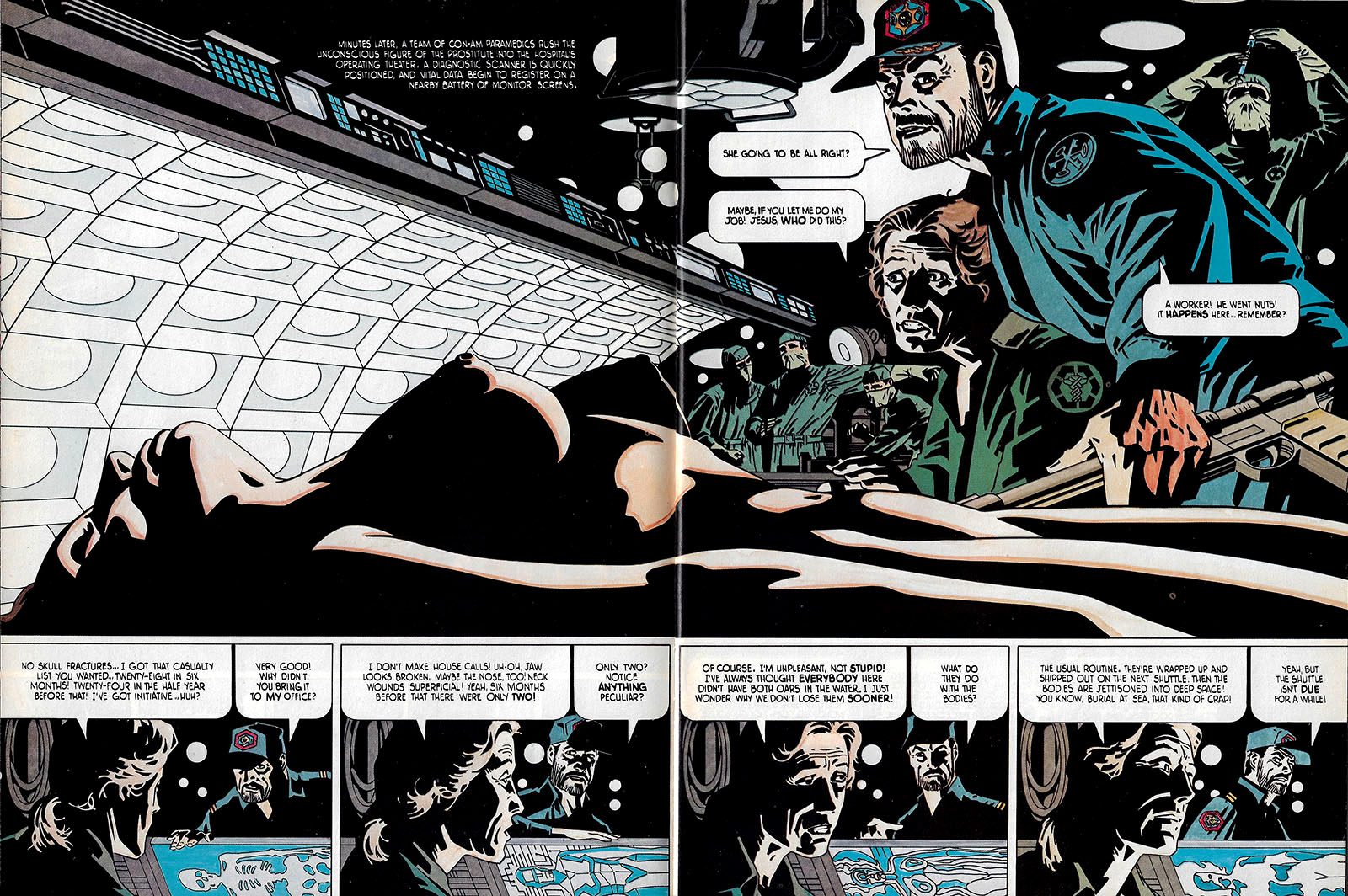

In 1981, Steranko crossed paths with Outland, and the results were unlike anything seen before or since. Whereas most comic book adaptations require 4-6 issues (100 to 150 pages), Steranko captured Outland in just 44 pages. They were serialized over five issues of Heavy Metal magazine, which specialized in experimental storytelling. Rather than attempting to reproduce complex action in his scenes (which always explode the page count), Steranko stayed on that bridge he built, delivering an illustrated narrative that blended graphic design with comics to expertly capture the visual tone of the film. It’s about as close as anyone has gotten to engineering a “widescreen” experience on the page.

It’s something you need to see for yourself, and for me to say more would be to rob you of the experience. So I’ll close by making my main point, which is that this lucky confluence of talent and subject was a direct result of the media environment of its time. It’s an inescapable fact that the evolution of media since then has, ironically, resulted in…less media. With it went opportunities for craftsmanship like this. We can only wonder what visual treasures we might have seen if those conditions still existed today.

Introduction from Heavy Metal June 1981 issue

Outland is adapted and illustrated by award-winning author and artist Jim Steranko. Based on the science-fiction thriller film written and directed by Peter Hyams, the graphic story version of Outland will be presented in four full-color installments, each eleven pages in length, beginning in the next issue of Heavy Metal.

Outland will showcase Steranko’s first comics work since his highly acclaimed Nick Fury and Captain America series for Marvel in the late 1960s. The style and format used in this adaptation are highly experimental, and designed to specifically complement the story. Outland is a Ladd Company production, released through Warner Brothers.

RELATED LINKS