Secret movie project, 2004 (part 2)

As I said in part 1, Twin Princes started out as a dream. Out of nowhere, the chance to visualize an entire 90-minute fantasy adventure movie that would be animated in realistic CG. At the beginning, I felt like I had accumulated exactly the right skills and experience to direct it. And just as importantly, I had found friends who I trusted to help.

I also had a client who told me something no one else ever did, before or since. When we signed the contract to get the engine running, he said, “Do what only you can do. Bring your dream to life.”

Those may not be the exact words spoken to me by In-Hyung Hwang, the Korean exec producer who had originated the project, but that was the exact sentiment. It filled me with inspiration and confidence. From there, he deputized his LA-based producer, Youngman Kang, to interact with me and my team in weekly meetings as things took shape.

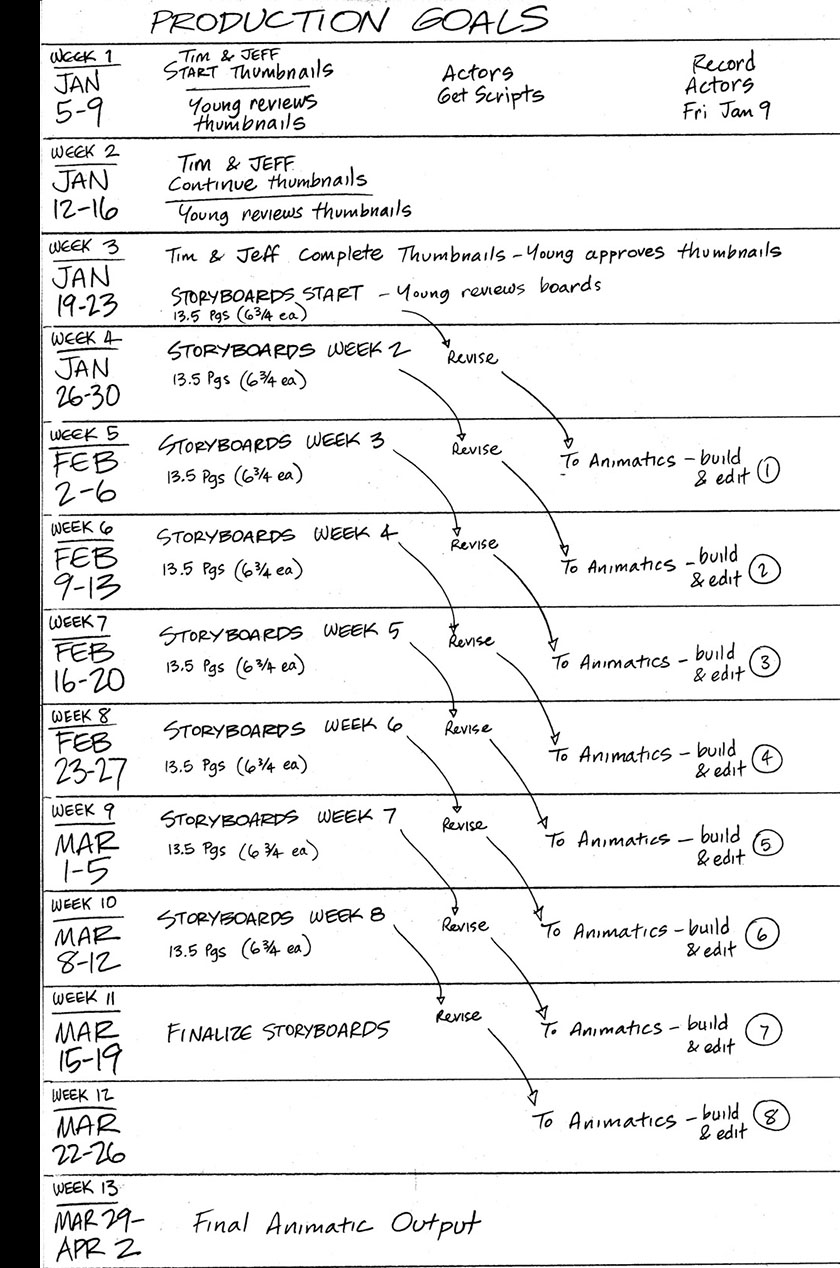

In the biz, this roadmap is called a “cascading schedule.”

I created a schedule that mapped out what we had to do for the 13 weeks we would be in production. At the end of that stretch, we would have the finished animatic with a temp soundtrack of voice actors, music, and some sound effects. We would be paid upon startup and then at the 1/3 and 2/3 points. We got the voice recording done on time and I found an animatic editor who agreed to my budget and schedule, so all systems were go.

How, then, did this turn into a nightmare?

There were two fail points that I didn’t see coming. The first was my fault, the second was impossible to anticipate.

Point 1 was that I assumed my allies on the storyboard side (artists Jeff Allen and Don Hudson) would be available to work with me all the way through. Instead, they both got other offers and had to bail. I couldn’t blame them. This was only a 3-month project and they were being hired to work on TV shows that would last much longer. TV work was seasonal back then, and the first quarter of the year was when new shows went into production. Before we even got to the halfway point of the movie, Jeff and Don were both off the map.

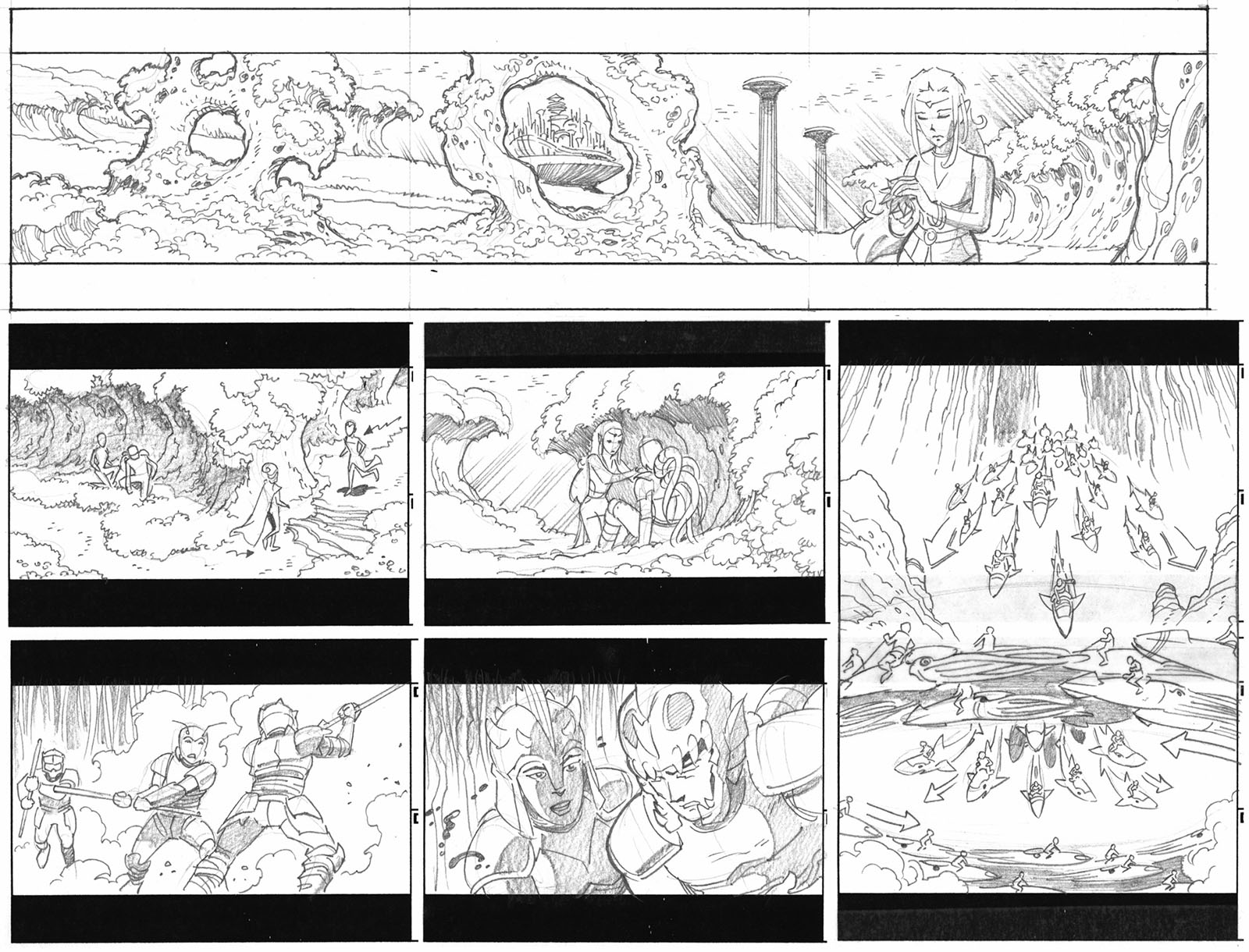

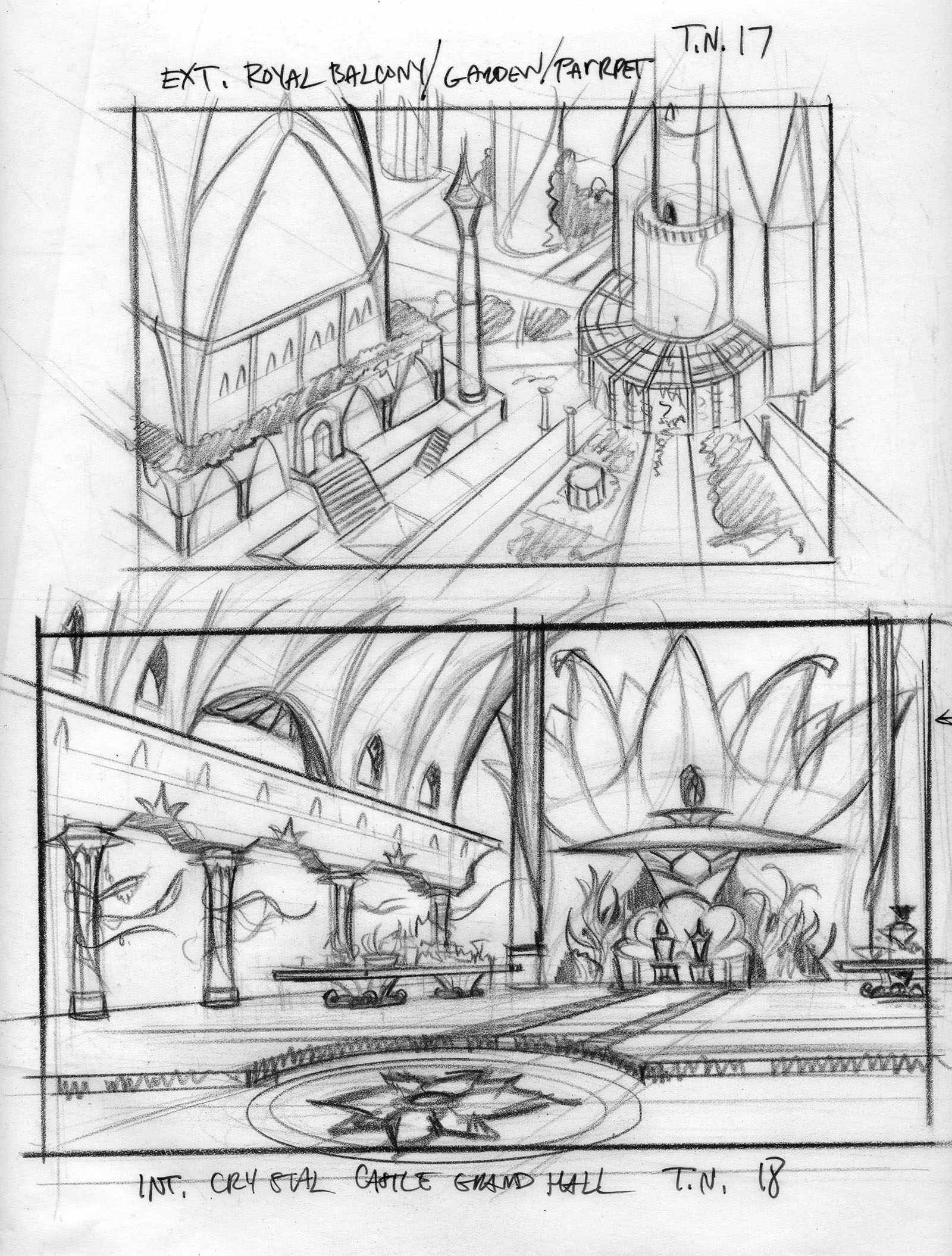

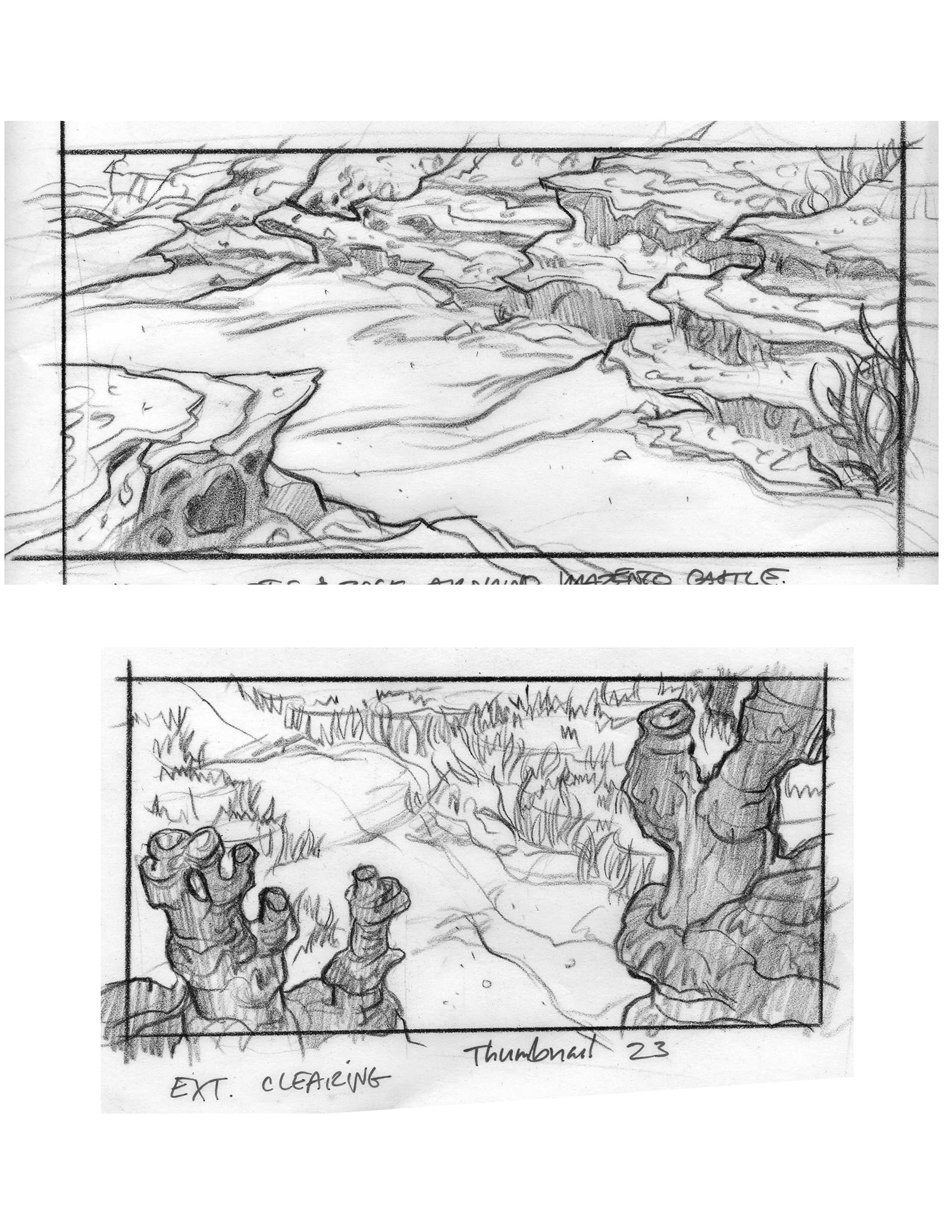

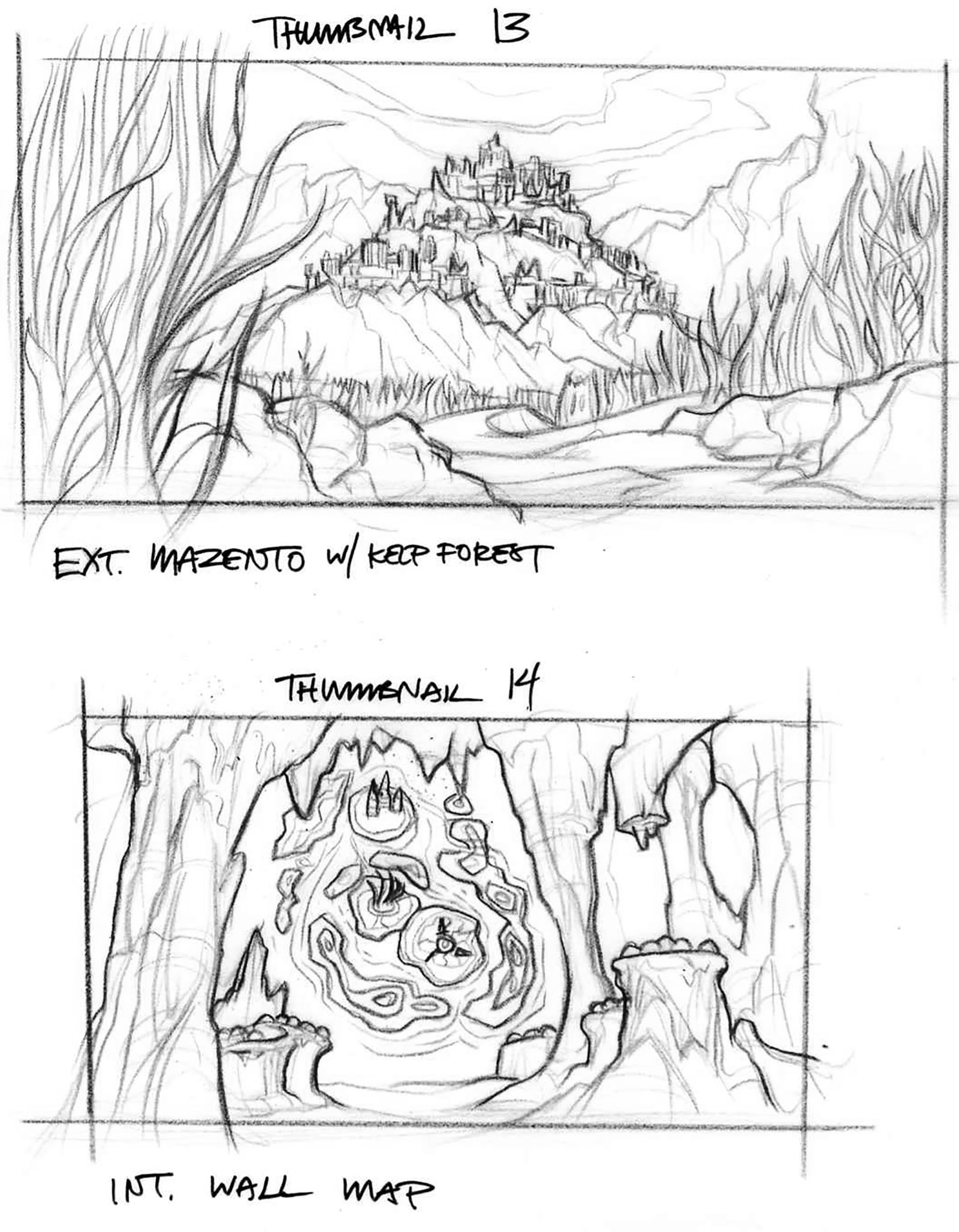

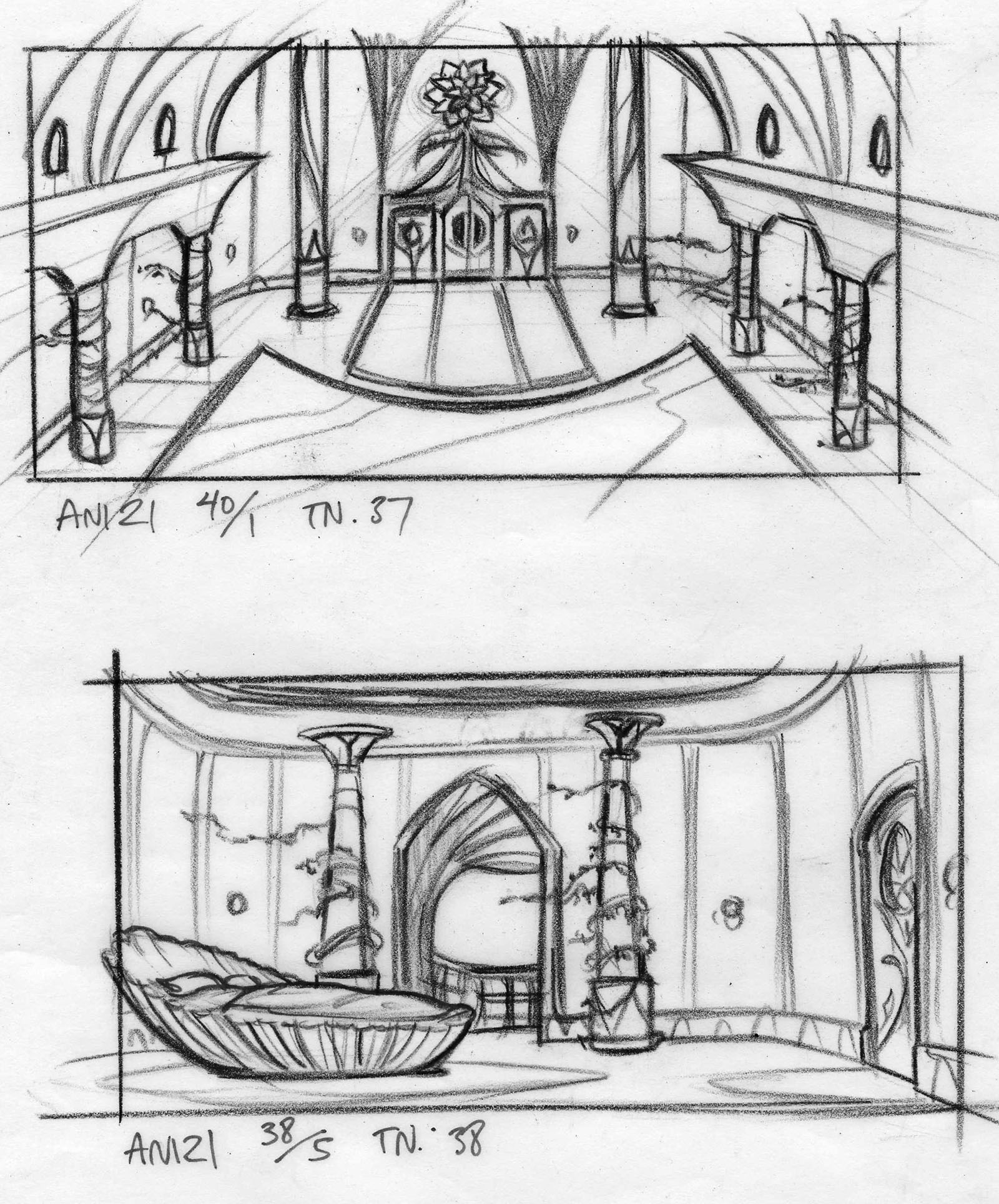

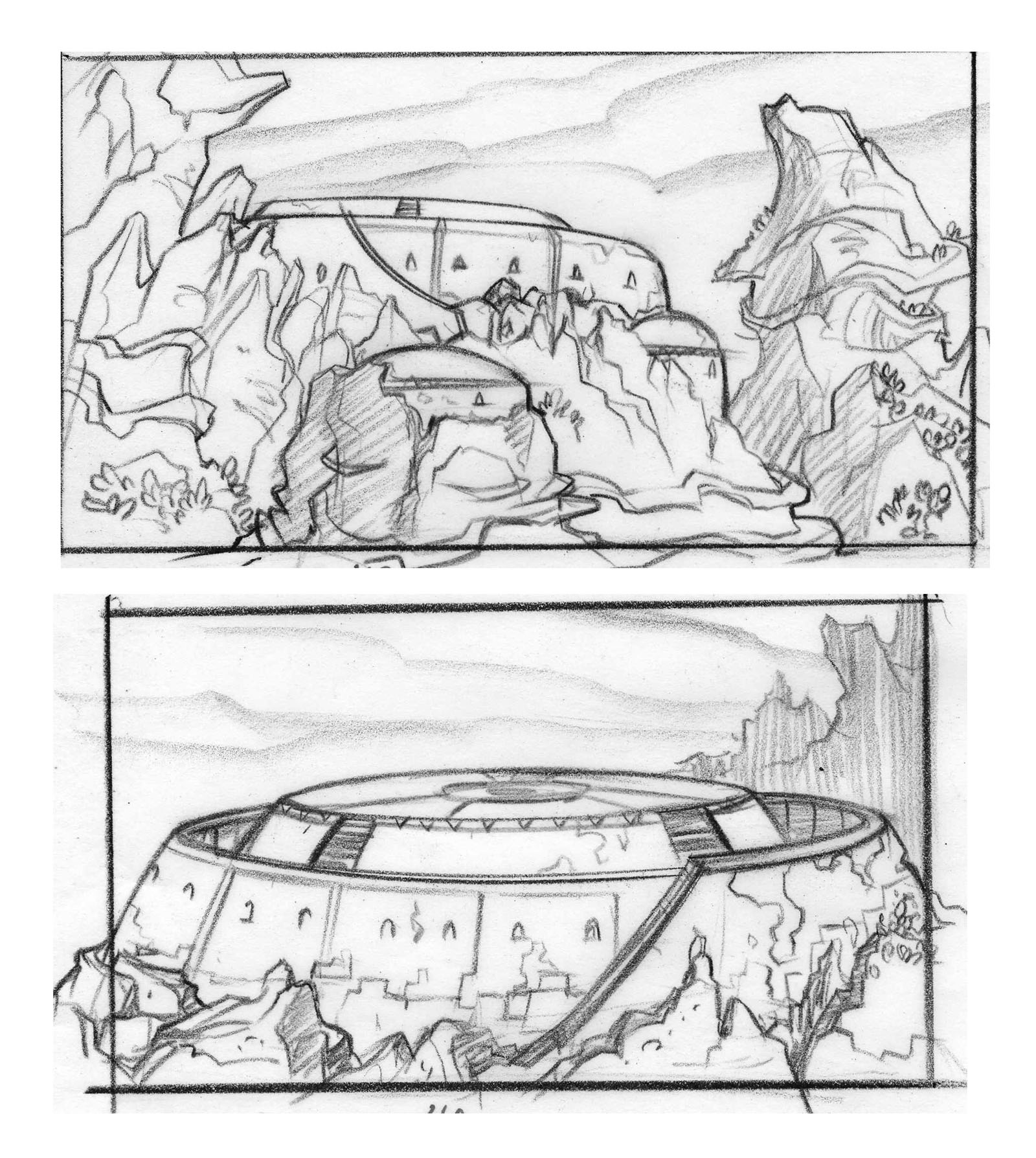

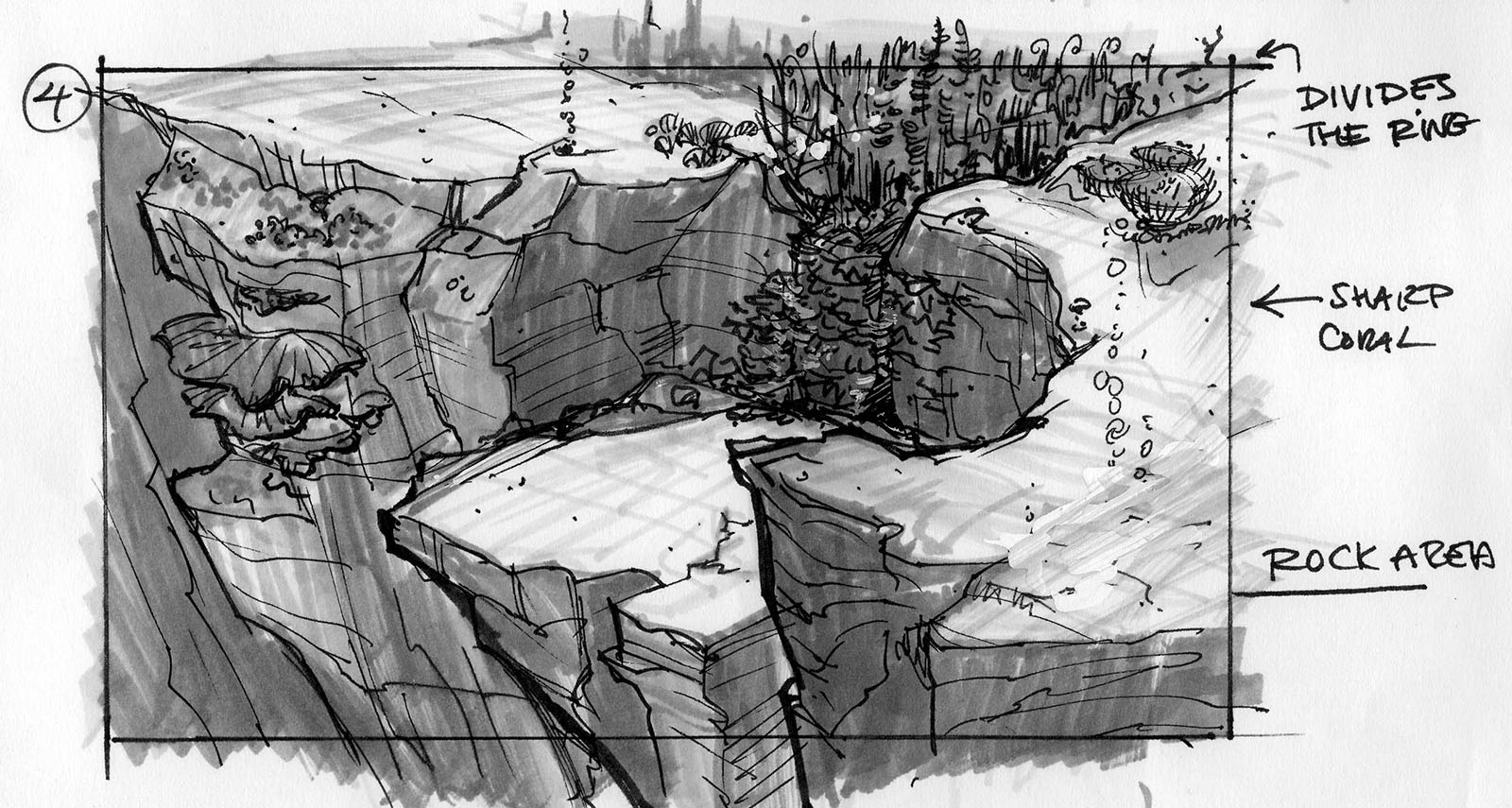

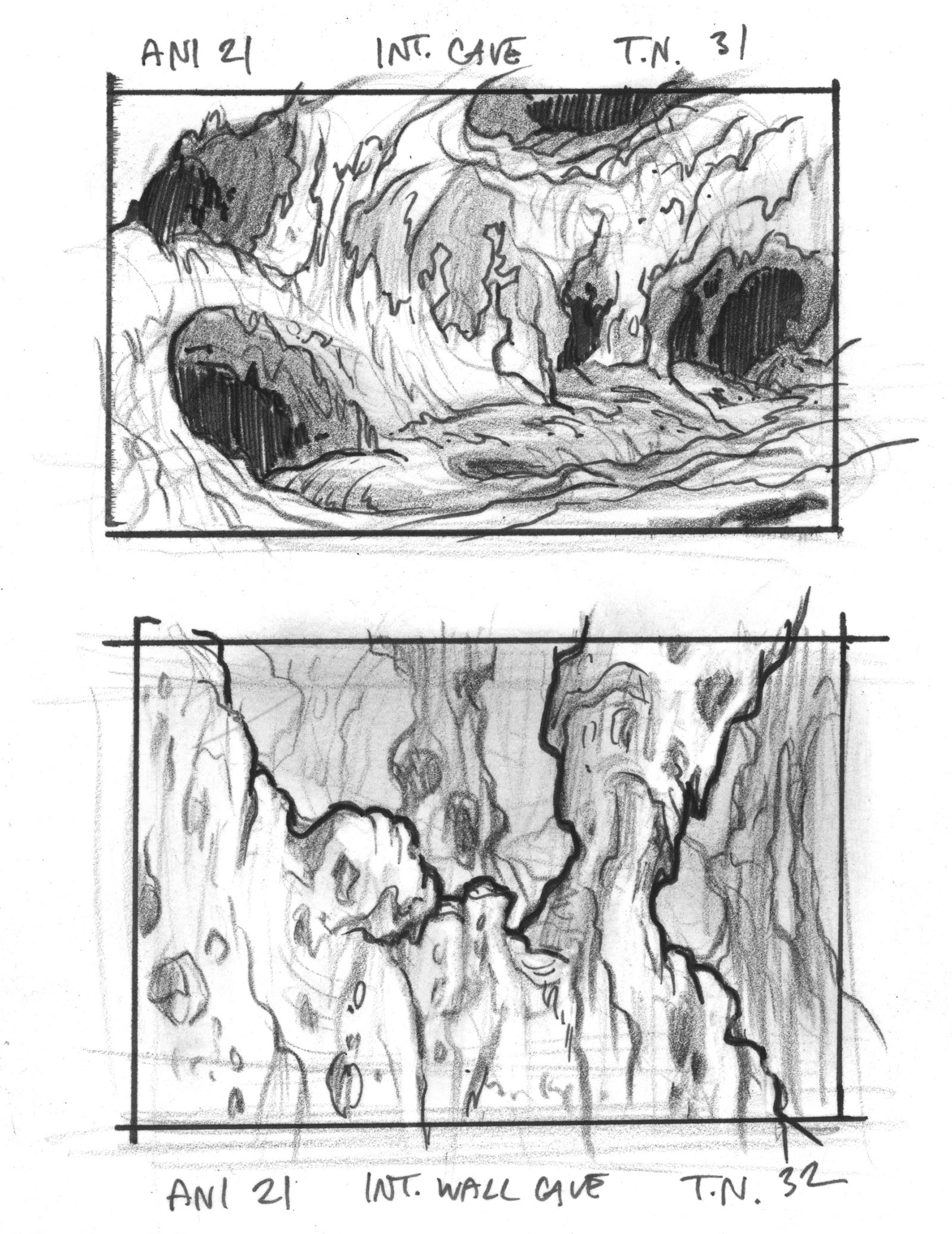

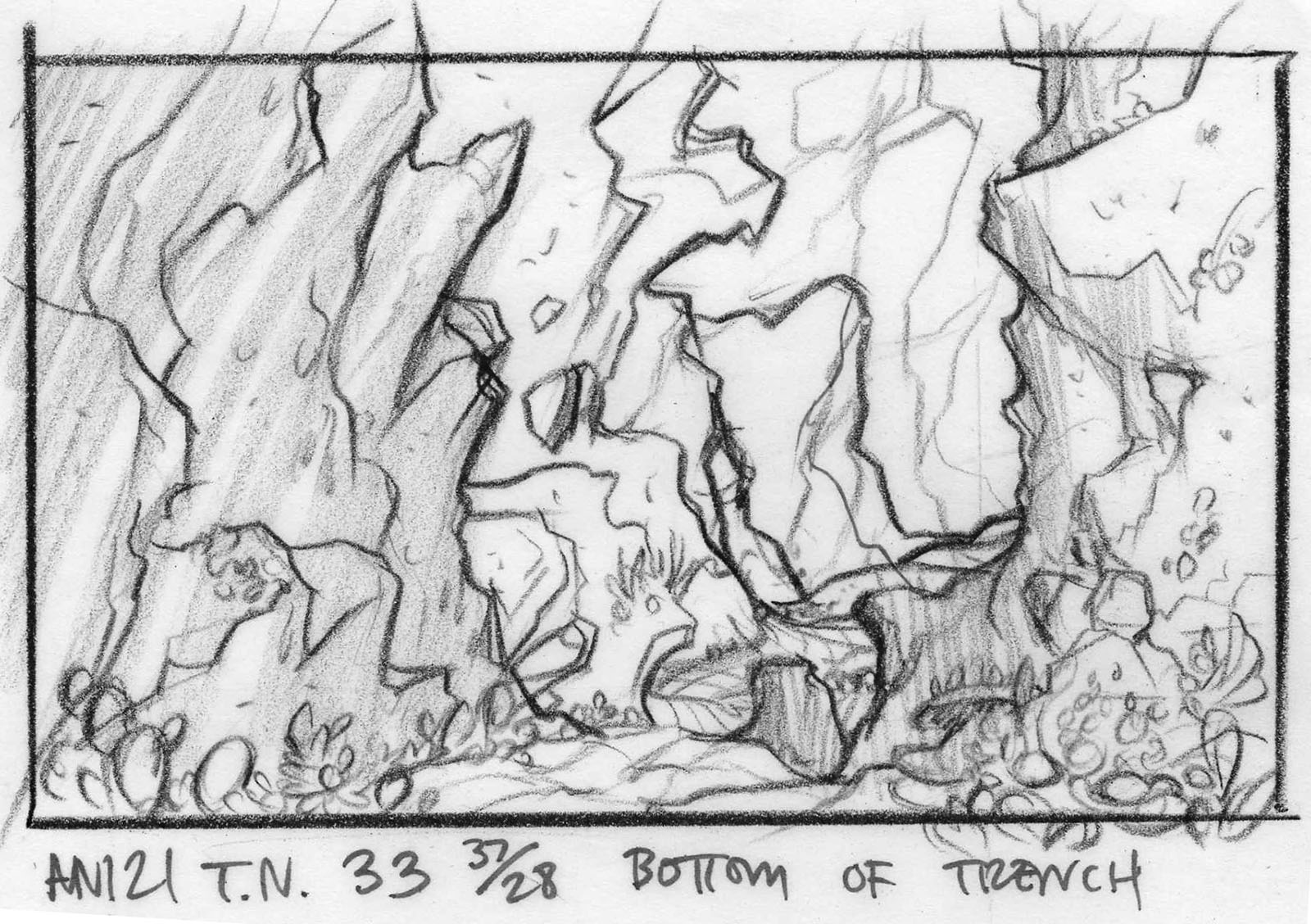

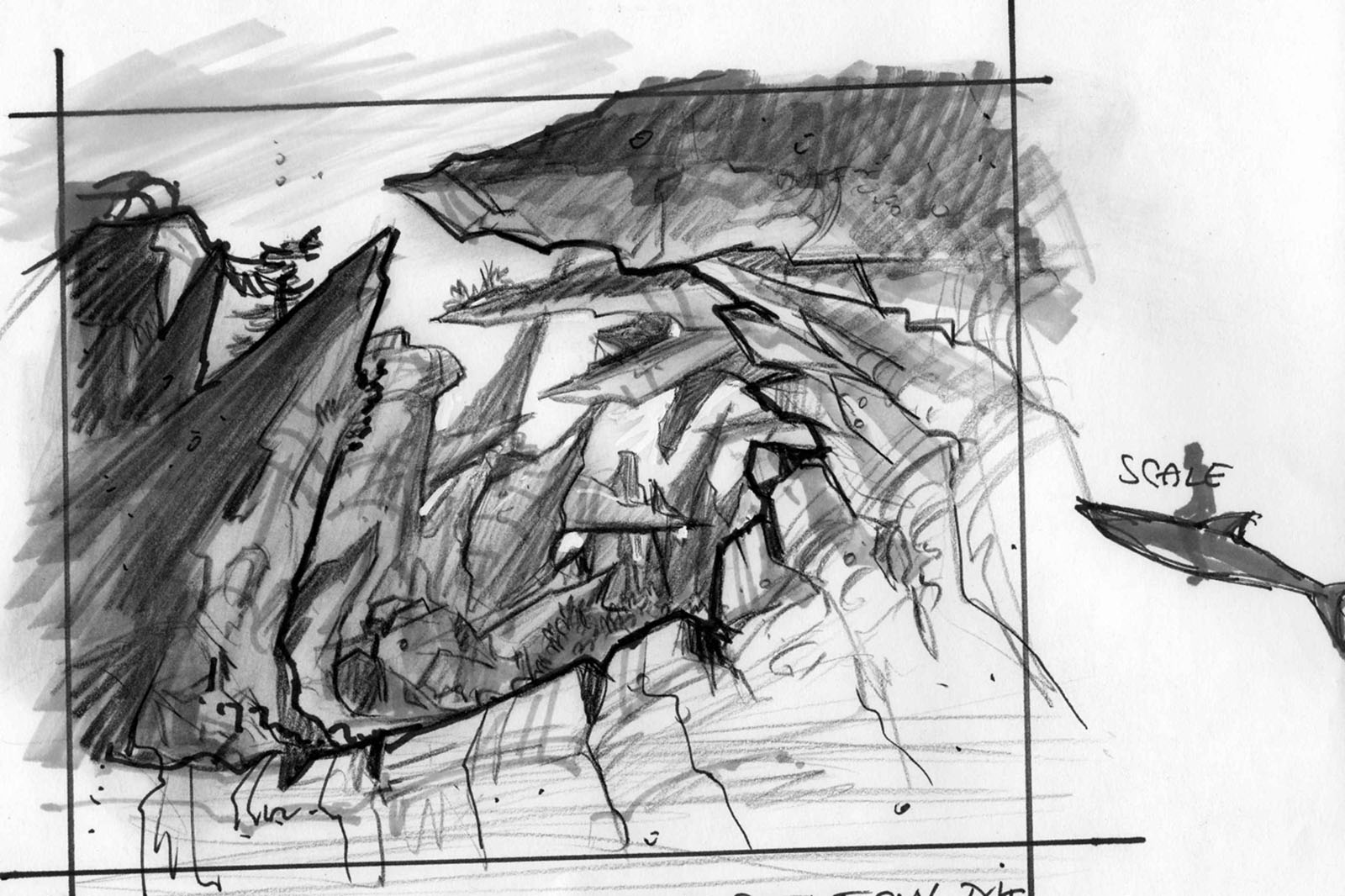

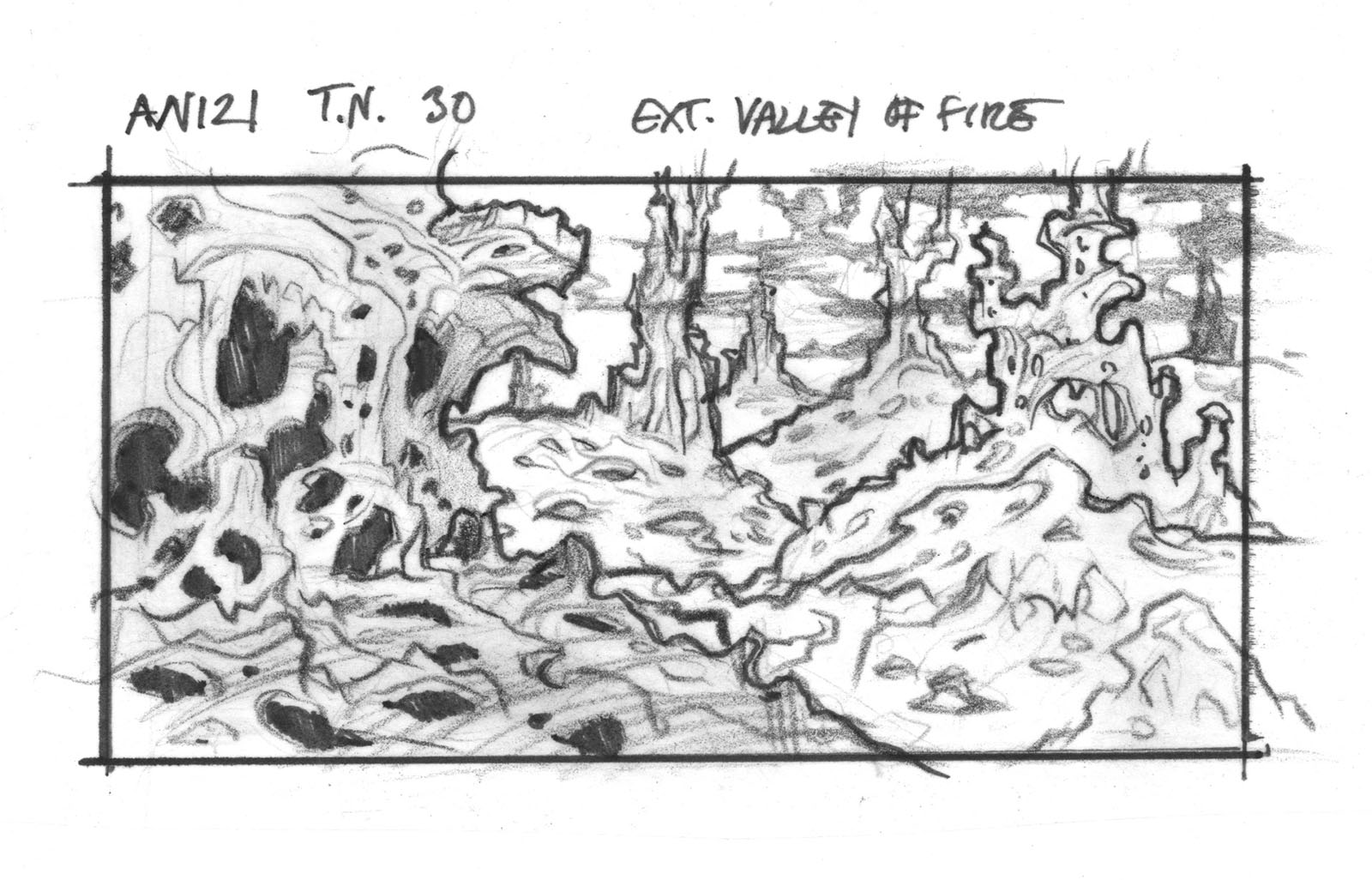

I was still committed as the director, so I had no choice but to take on their workload until I could find more help. As you can imagine, it wasn’t easy with TV jobs snapping everyone up. I managed to find only one other artist, Dell Barras, who was both available and skilled enough to take on the work. The entire film had been thumbnailed in advance, so he didn’t have to work directly from script. All the scenes were pre-designed, so he only had to render them in finished form.

This, in fact, was the lifesaver. If we hadn’t gone through the thumbnail phase at the beginning, it would have resulted in an impossible workload. However, Dell could only replace one of the two guys I’d lost. I had to take on the work of the other guy, plus my own. So I was personally drawing 2/3 of all the storyboards each week rather than the 1/3 I’d planned for.

Don Hudson got a break somewhere down the line, and was able to contribute a bit to the second half of the film, which offered some partial relief. But I was still drawing at top speed and also doing revision work, right to the end.

Then there was point 2. This one came from above and completely blindsided me.

Week by week, I would turn over a copy of finished storyboards to Youngman Kang, who would then forward them to Mr. Hwang in Korea. Suddenly, the good will I felt at the start went cold and sour.

More than once, Young would start a conversation with these words: “Mr. Hwang, he not happy.”

It took some back and forth to get clarity on this, but here’s what it came down to: he didn’t understand some of what he was seeing in the storyboard. Namely, he was being distracted by the shortcuts that we had been taught to use from the beginning of our careers.

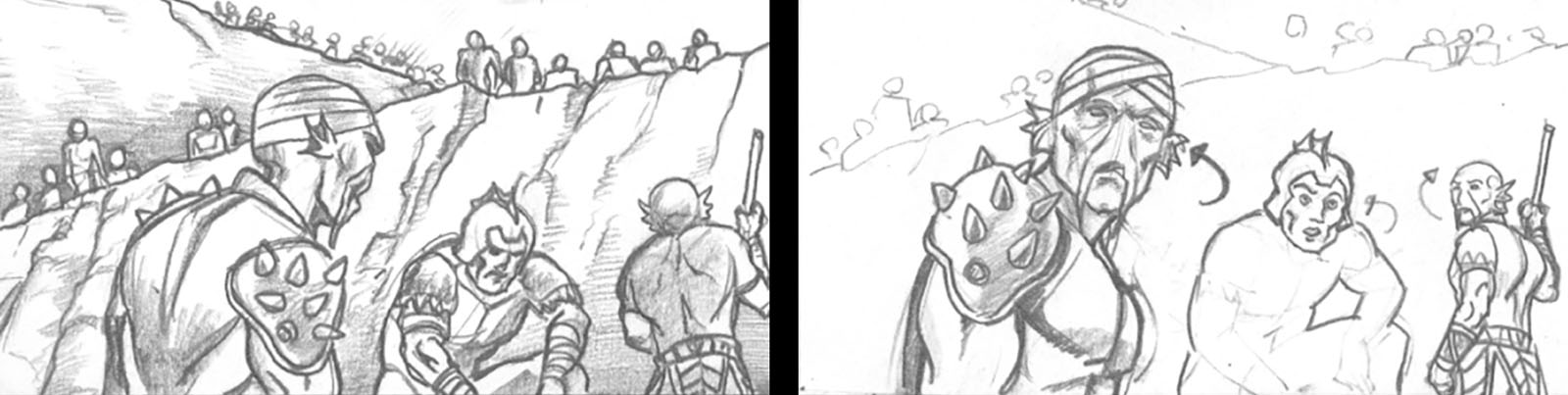

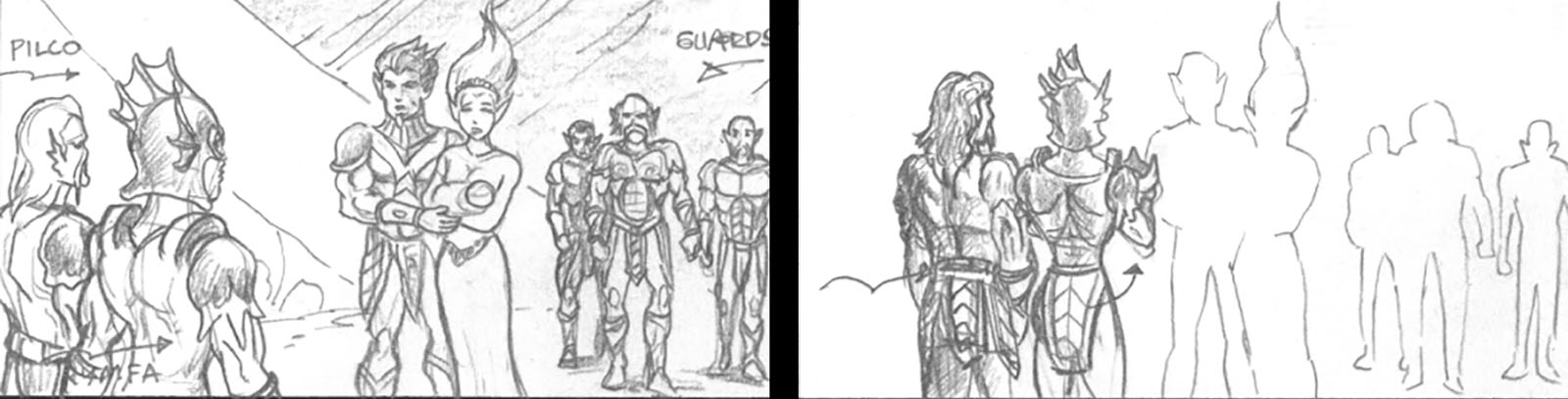

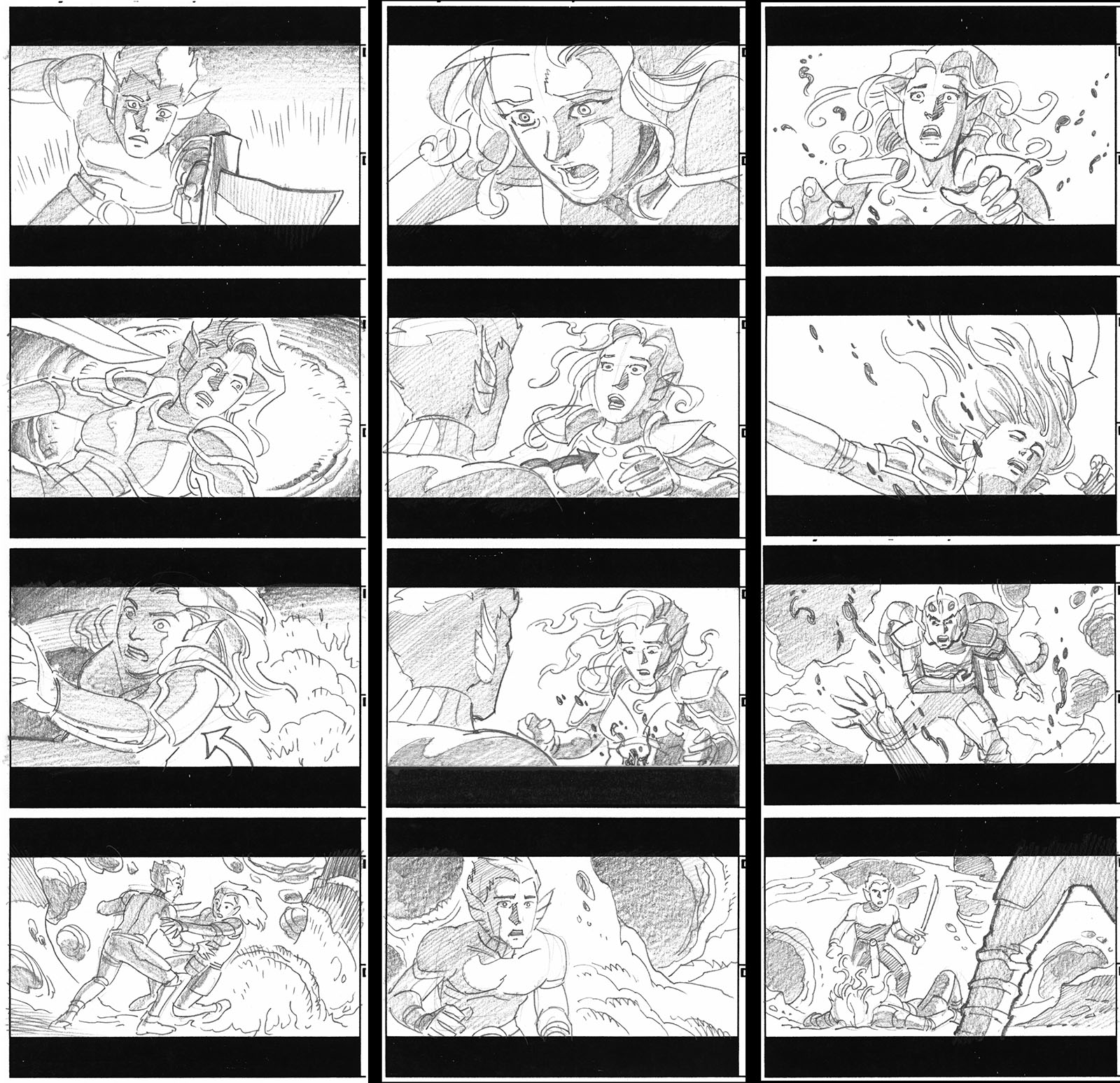

The formula is simple: when you have a lot of stuff to draw, you make it as simple as you can to meet your deadline. This means leaving stuff out when it becomes redundant. A prime example is shown above and below; if you have a storyboard panel where someone or something doesn’t move, it’s pointless to draw it over again. We’d just draw an outline based on their previous position. In other words, draw them in panel A, but then reduce them to an outline in panel B. Animators know exactly how to interpret that.

But if you’re not an animator, and you’ve never seen a storyboard before, this can be confusing. To you, it looks like a mistake. And that’s what Hwang thought. Every time he saw it, he assumed we weren’t doing our job, and – ultimately – trying to cheat him out of his money. It was the same with all the other artifacts of the craft that he wasn’t familiar with. I repeatedly responded by trying to explain how our craft actually worked, and that the time we saved with shortcuts was being used to improve the other drawings.

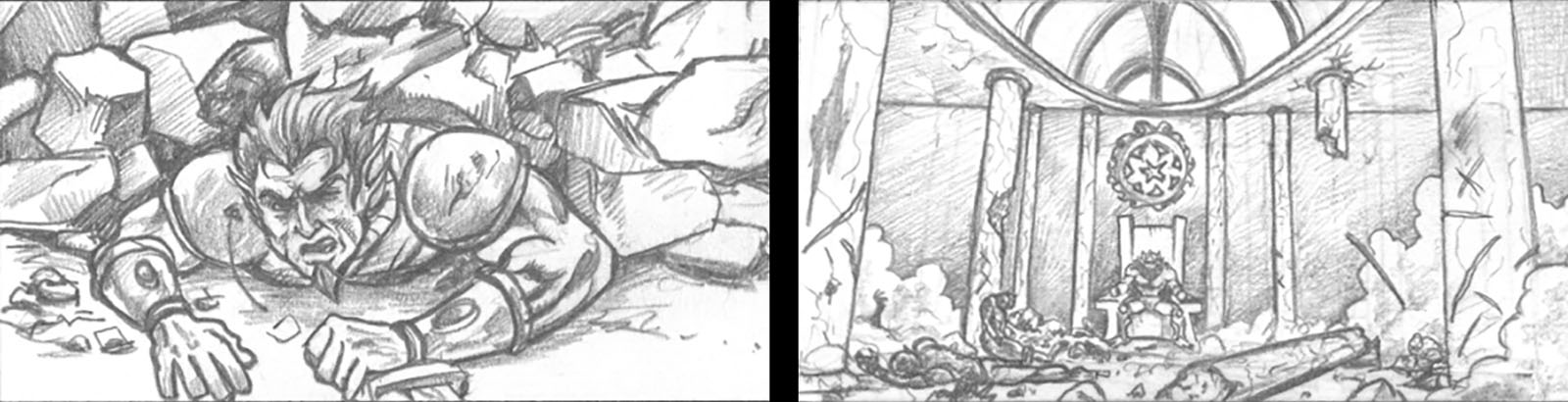

In fact, this was the most intricate and detailed storyboard we had ever done. You can see it for yourself in the animatics; the drawing quality went WAY beyond anything we’d do on a standard TV episode. As Hwang’s frustration grew, I pushed back by drawing even more detail, including “repeat” drawings. When we got to the battle scenes between underwater armies, every soldier had a unique pose and choreography. I was determined to beat any idea out of Hwang’s head that he was being “cheated.”

Storyboards by Jeff. They look incredible, but there’s a reason we don’t usually draw them this way.

Jeff Allen offers this comment:

The only thing that has stayed with me all these years is Youngman loving all the detail I added when I cleaned up Tim’s thumbnails. He wanted the whole thing to be drawn at that level! Of course Tim told him that was impossible and I felt horrible, especially when he complained that Don’s cleanup looked like shit. I’ll never forget the look on Don’s face as Youngman trashed his work in front of us. It’s actually burned into my frontal lobe. Stupid me couldn’t help getting all intricate with my cleanup and it ended up causing a huge pileup on the Twin Princes Expressway.

Overall it was a fun experience working on a movie with Tim and I’d do it all over again if I could. Except this time I’d take it easy on the detail and have less hair.

As more weeks went by, I kept hearing the same infuriating words. “Mr. Hwang, he not happy.” As we approached the 2/3 point (and the final payment), Hwang decided to fly in for a face-to-face meeting. I took this as an opportunity to educate him on exactly how much he was getting for his money. I pulled out stacks of previous TV storyboards I’d worked on so he could see what the standard was – and how far above the standard Twin Princes was. I even called in a Korean storyboard artist I’d worked with (named James Yang) who could convey this in their native language.

The meeting happened in my living room. I remember it was an unusually sunny day after a spate of rain, which was interesting timing. Hwang came in with Young and an interpreter, a sour look on their faces. Everyone was surprised to meet MY interpreter, which put some spin on the ball in my favor. The conversation began with points and counterpoints.

What James related to me was unexpected. Hwang thought I had misrepresented myself in our first meeting (back in December ’03) when I showed them my homemade Grease Monkey animatic (see it here). It wasn’t fully animated, but it had the look of a finished film with color and sound. I thought I’d made it clear that the budget and schedule wouldn’t allow me to take Twin Princes to that level. Grease Monkey was a 17-minute piece that took six months to make, whereas this film was 90 minutes and we only had half the time. Obviously I didn’t make that point clear enough, so I made it again.

Hwang reluctantly flipped through the TV storyboard samples on the table as I explained that they represented the usual quality level, with shortcuts aplenty. Comparing them to a Twin Princes board was like night and day. James was the perfect guy to convey this, since he came up the same ladder I did and could relay it from personal experience. By the end of the meeting, Hwang got it. He still wasn’t happy, but he got it. And he released the final amount of money to finish the film.

In the wake of this, we talked about a followup project in which we would take ten minutes of the animatic and polish it into a pitch, color and all. I wrote up a proposal with a finishing date of June 30, but that’s as far as it went. Just as well. After all that conflict, I was ready to be done with Twin Princes forever.

For me, the best part was the animatic edit. Each week, I would get to spend one afternoon with an editor at his studio, seeing how everything came together. His crew had scanned all the storyboards into digital form and plugged them into Adobe Premiere to be timed and combined with sound. It was easier for them than most other shows, which often needed picture surgery and tricky compositing. It was basically a slideshow; one image at a time with dialogue tracks. The timing needed adjusting, but we only had to cover about 12 minutes a week so it wasn’t overwhelming.

Then we got to do the REALLY fun part, which was laying in a temp music score. I’d scoured my soundtrack collection (both movies and anime) and found pieces that I thought would work well. A few sound effects, too. After a section was timed, we’d experiment with adding music and found some absolutely dynamite combinations. If the movie got made, this sound would be tossed out and replaced, but for me it was where all the emotion packed into the scenes got validated. For me, this was the finished product.

When it was all done (right on schedule!), I handed everything over to Youngman Kang and went off to get married.

I didn’t mention that part, did I? My wedding date had long before been set for April 4th (4/4/04) and the final animatic output took place the week before. This meant that on top of all the pressure of making Twin Princes, I was also planning a wedding with almost the same deadline. And boy, did I appreciate that honeymoon. Don’t try this at home, kids.

AFTERMATH

As you may be aware by now, Twin Princes did not, in fact, get made into a major motion picture. Or even a minor one. To the best of my knowledge, Twin Princes wasn’t made into anything at all after I washed my hands of it.

When I asked screenwriter Brooks Wachtel what he knew of its fate, his answer was:

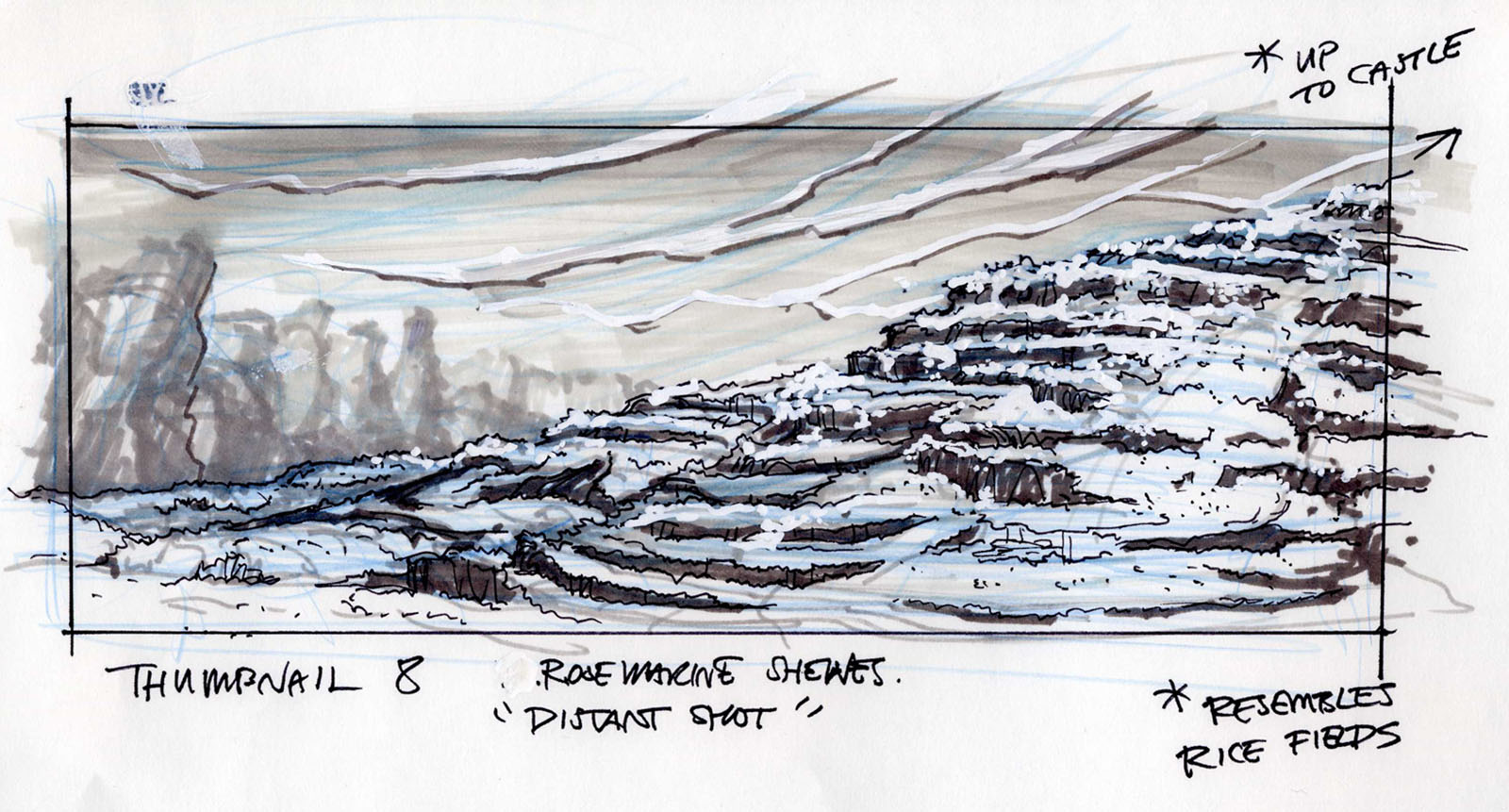

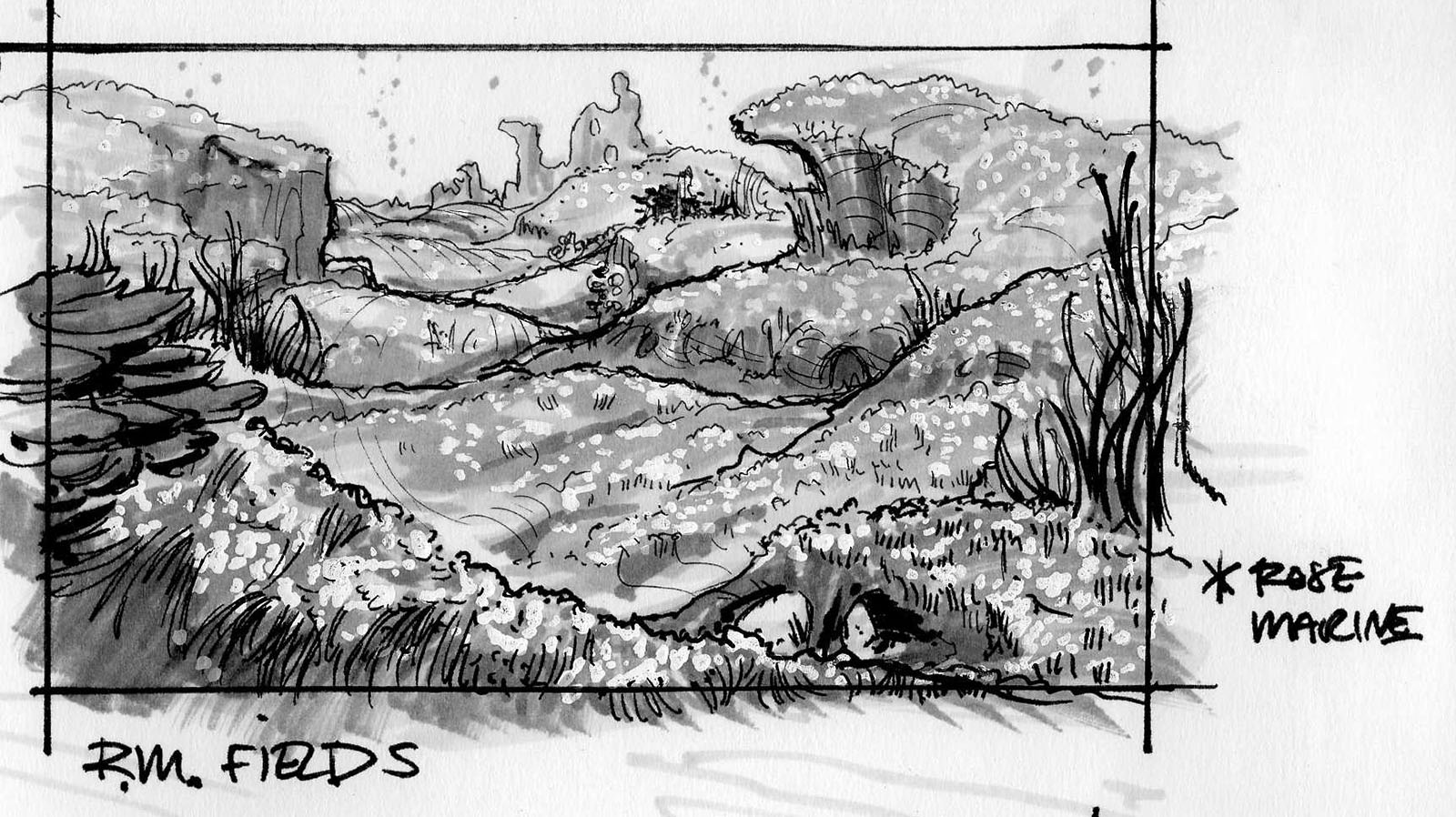

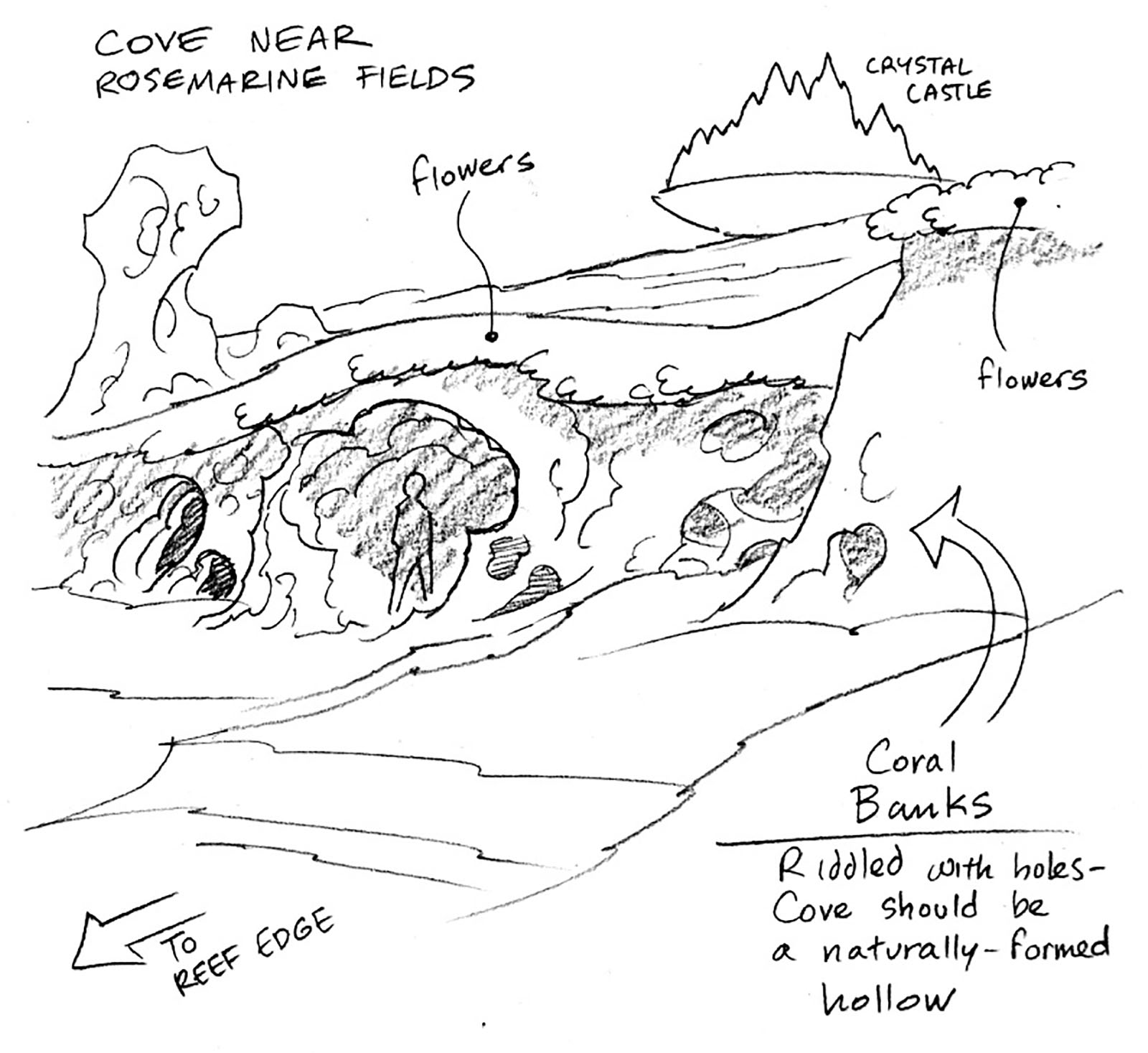

The funding fell out. I was working on a two script deal with them. I did write the second script, but never turned it in. I think Young stayed with the project for a while. It was renamed Rosemarine, and even had a short 3D trailer done (not certain), but it’s all history now.

Dream to nightmare to history. In the end, I’m very proud of the finished piece and I wish it had gone all the way to a finished film. (Even the animatic editor and his crew told me, “This HAS to get made.”) I’m also glad to have learned so much about my own adaptability and endurance. Every job that came after it was easier as a result. And for the time when I could immerse myself in the story, I liked where it took me.

In the end, that’s the only part that matters. Because that’s the only part history can’t swallow.

Animatic Part 5

Most storyboards by Don Hudson, me, and Dell Barras

Animatic Part 6

Storyboards by Dell Barras and me

Animatic Part 7

Storyboards by me, Don Hudson, and Dell Barras

Animatic Part 8

Storyboards by me, Don Hudson, and Dell Barras

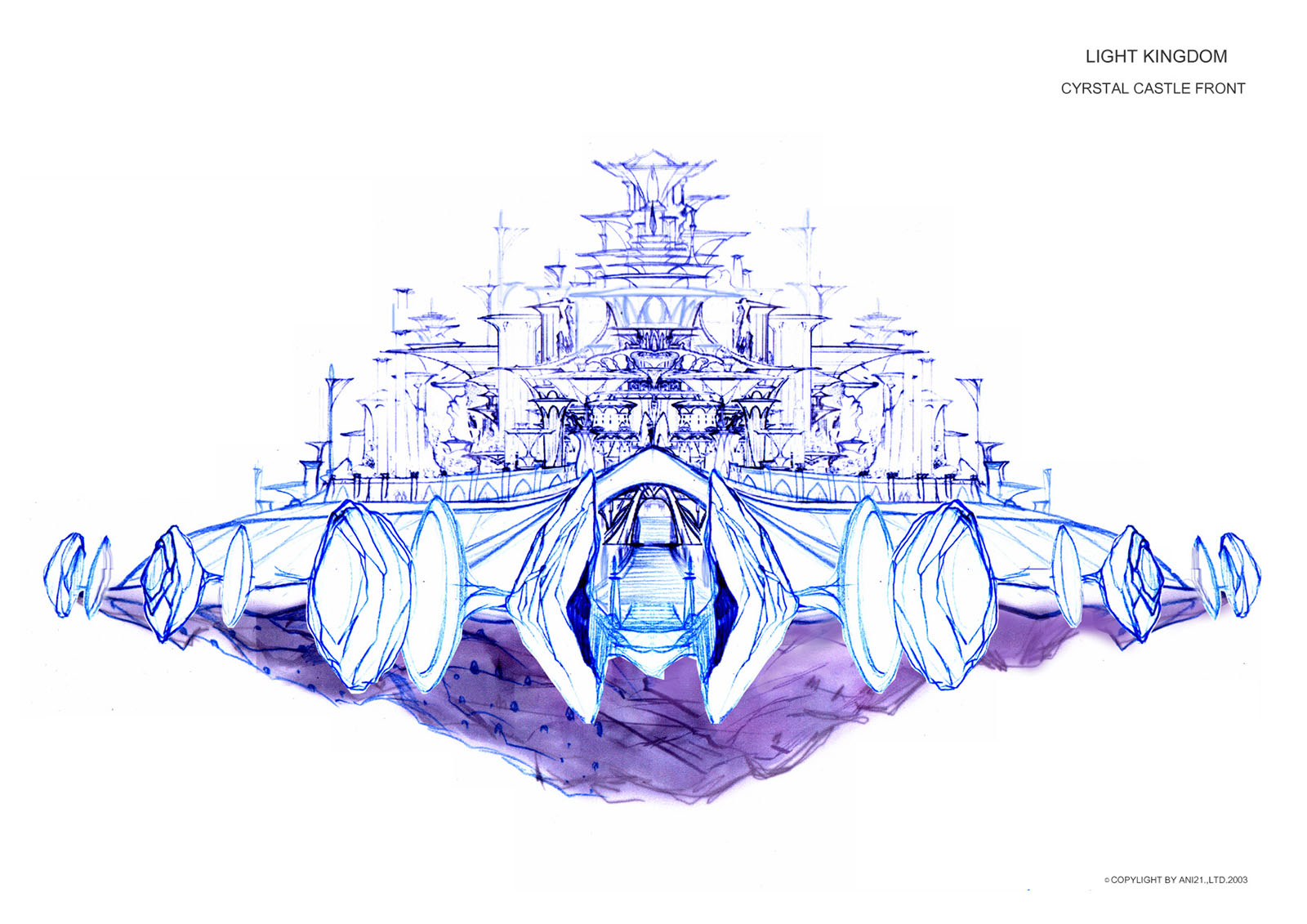

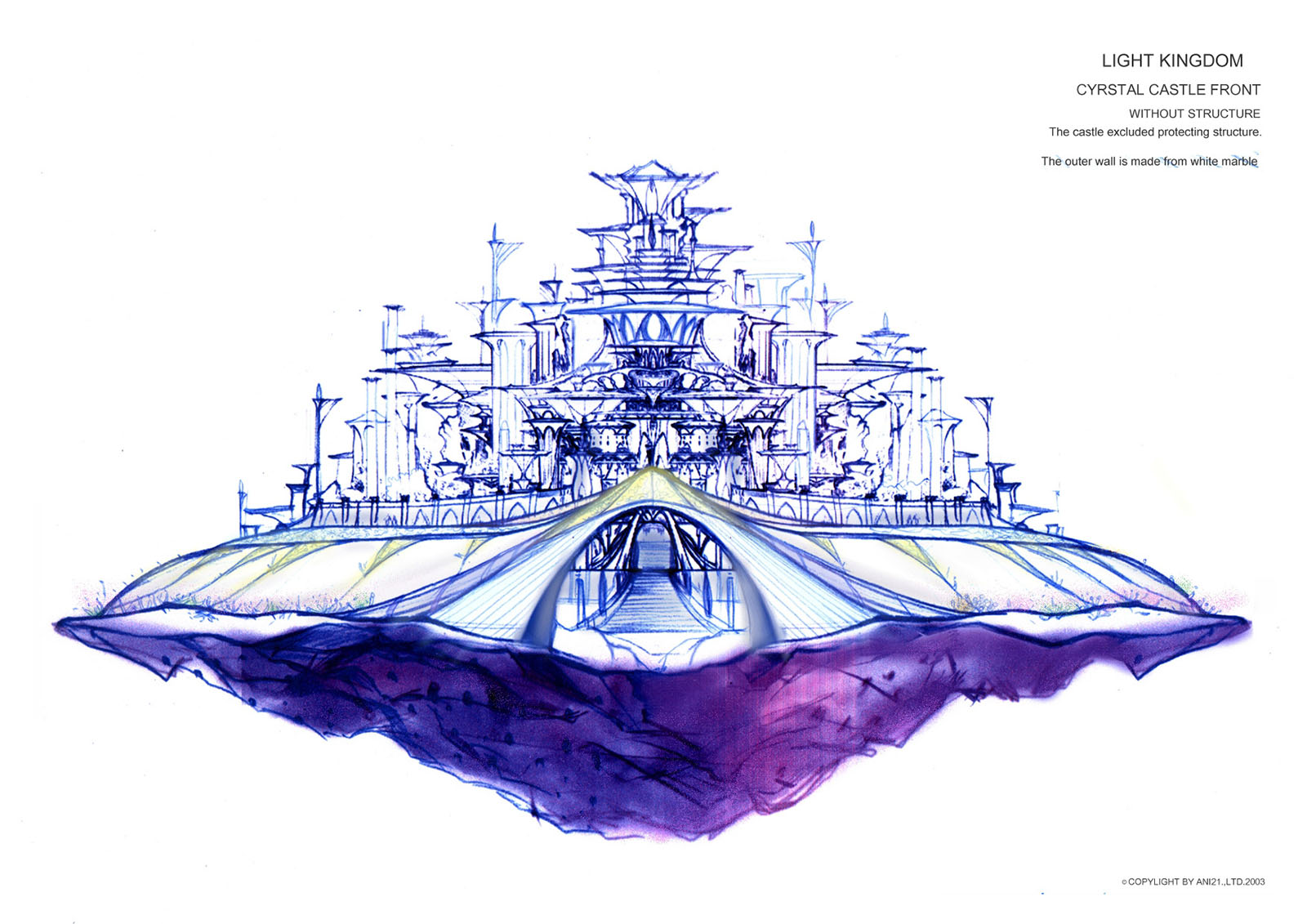

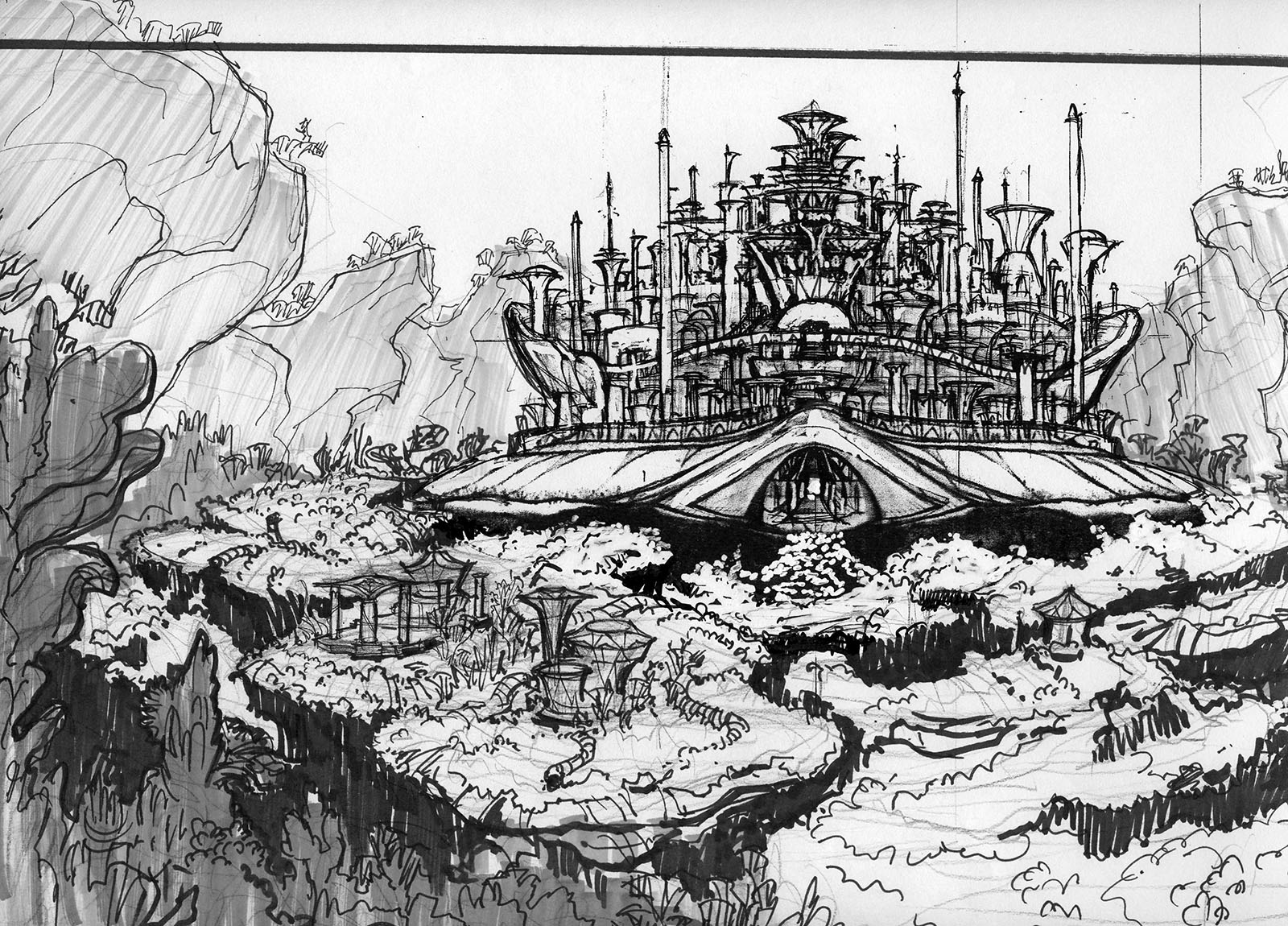

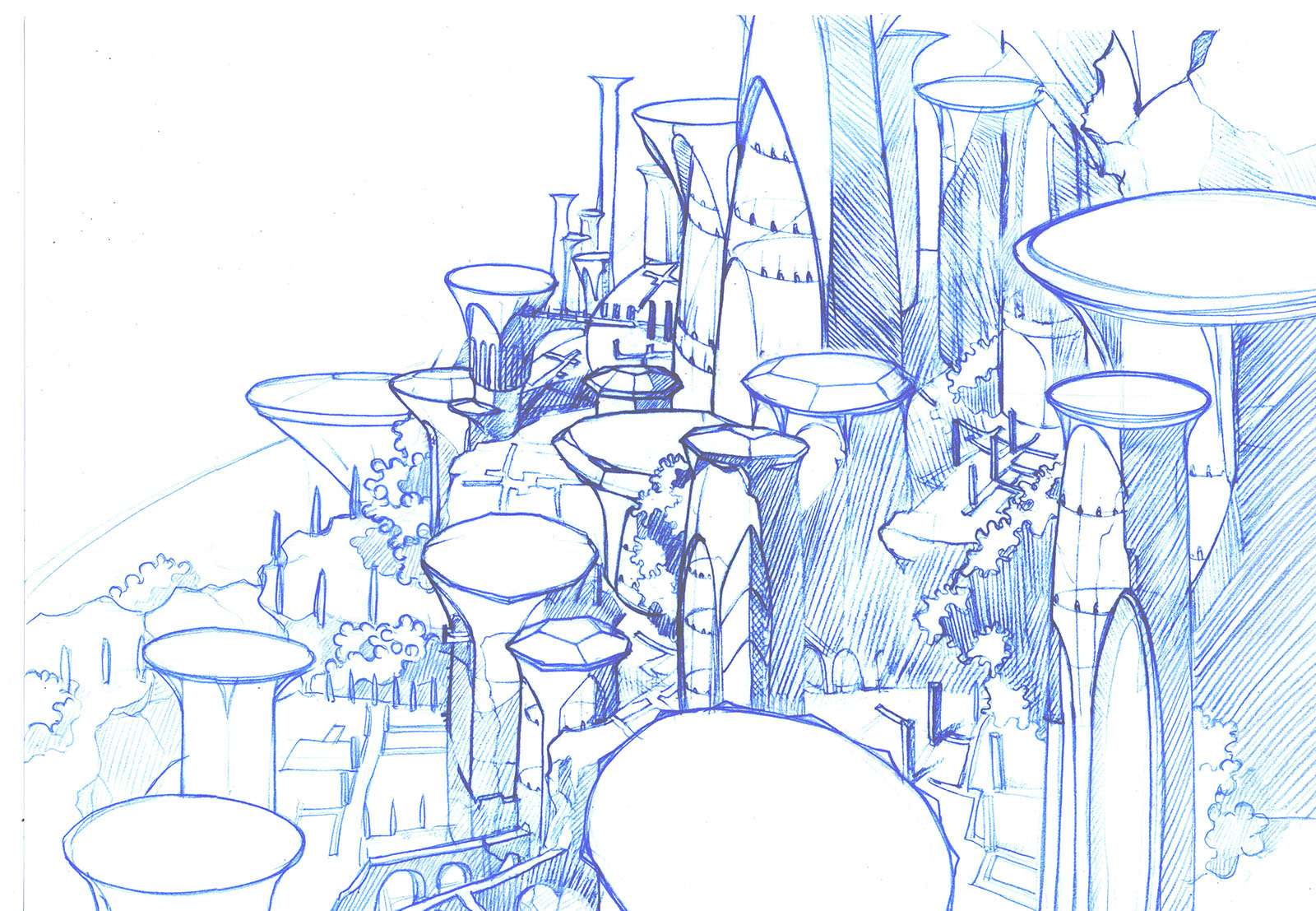

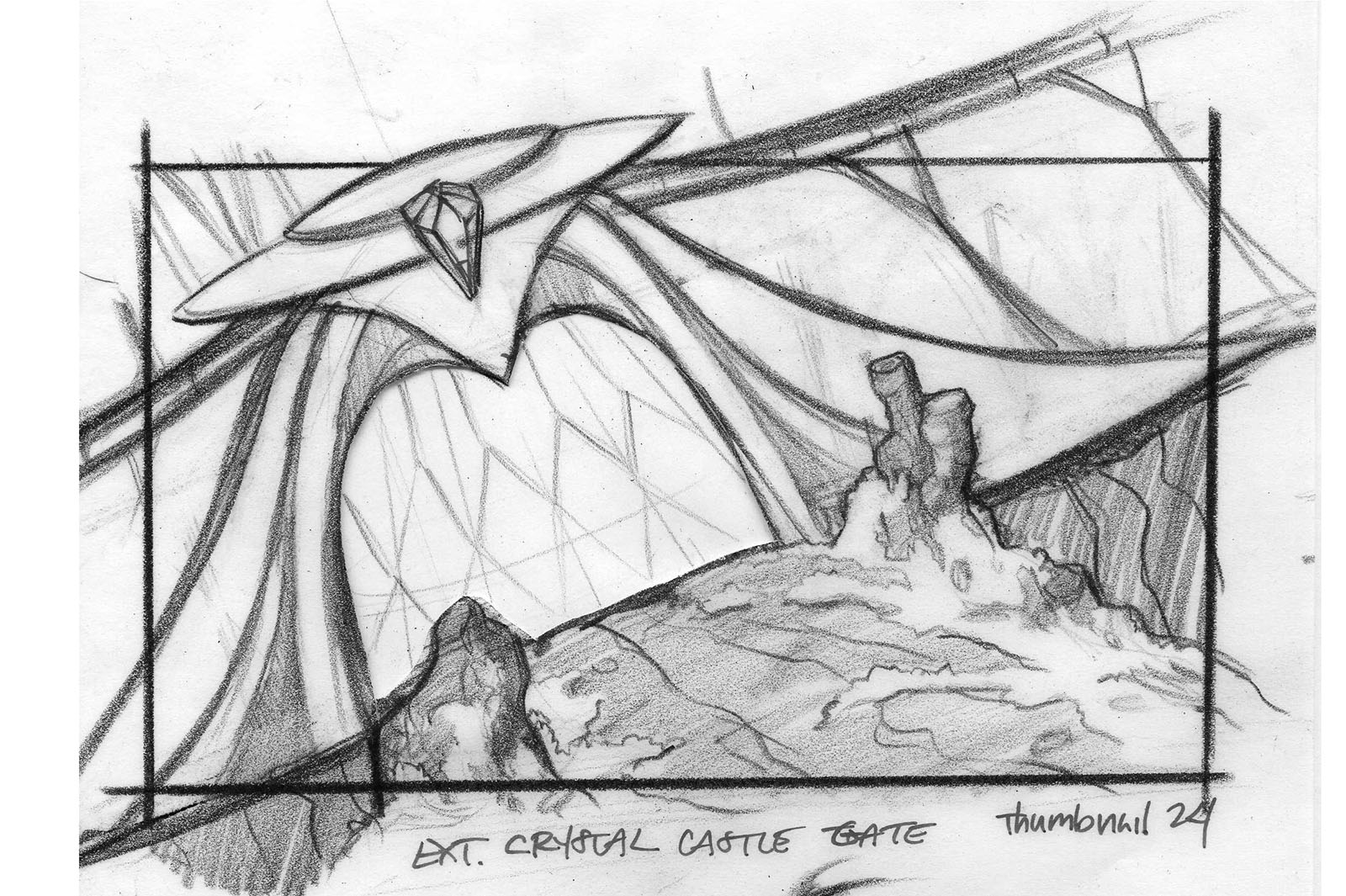

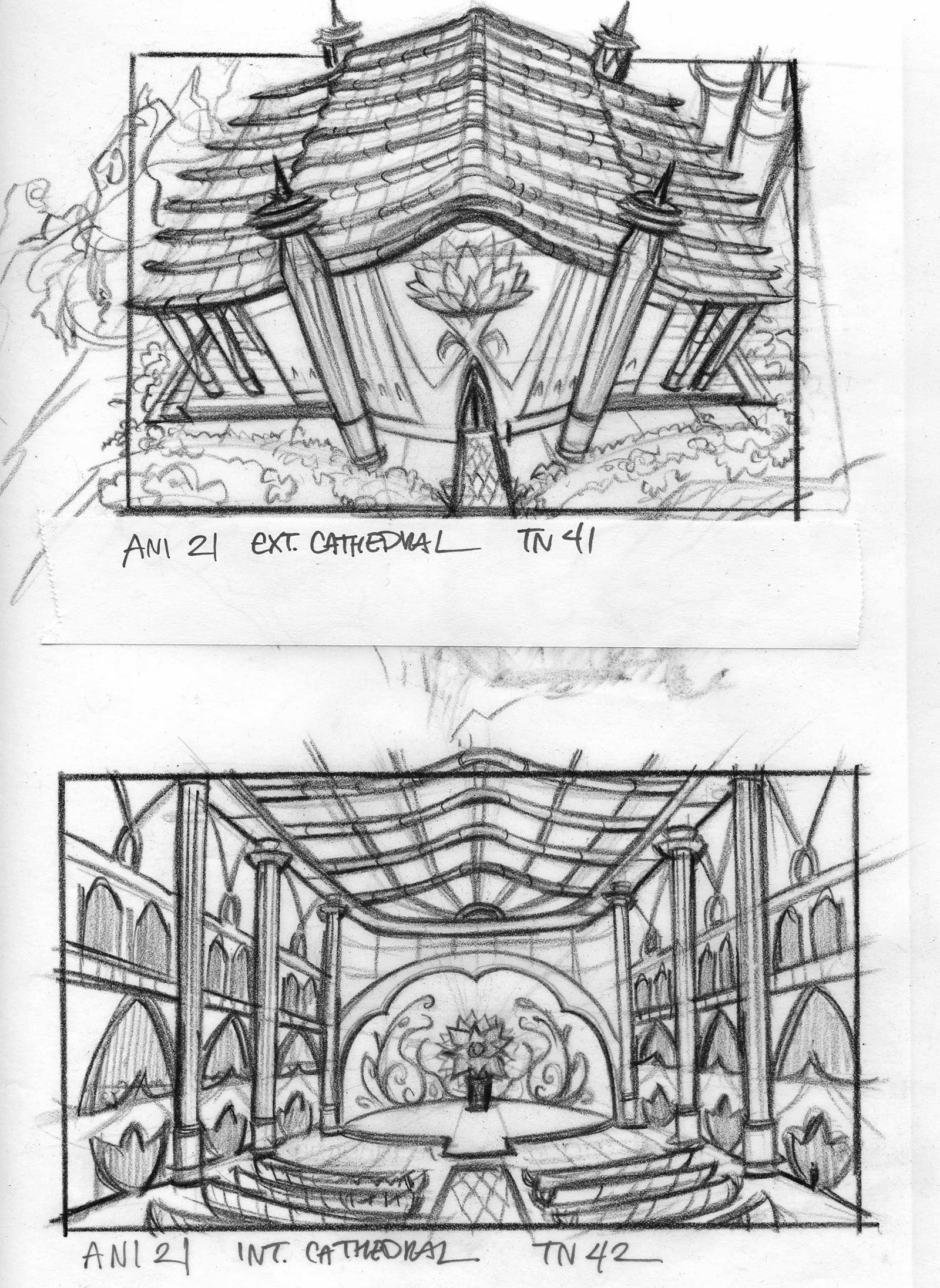

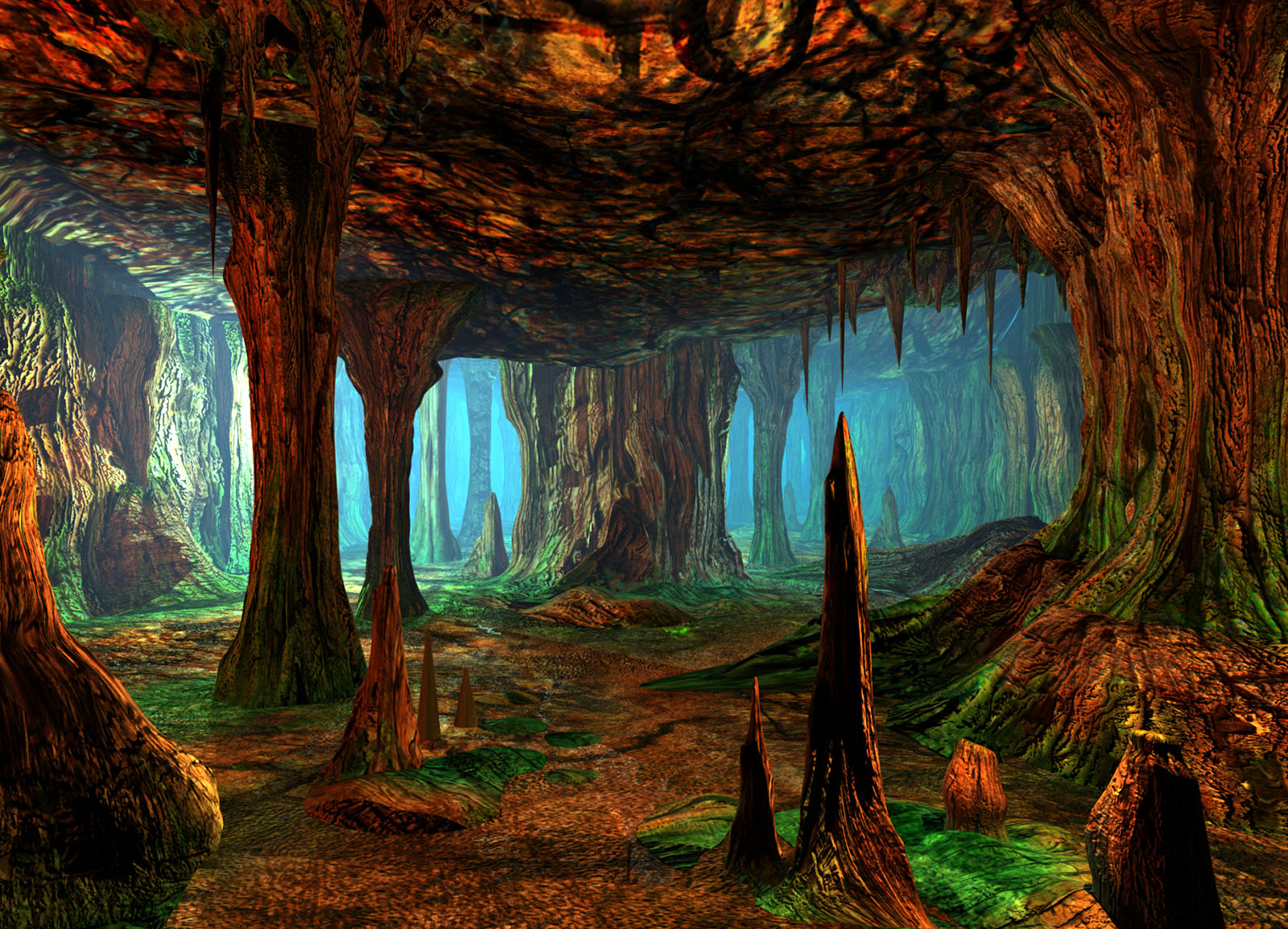

Production gallery: Background designs