Comics go to the movies: Blade Runner

I’ve had some great summers in my life, but few of them can top the summer of ’82. Many things changed for me that year. I got my first car, my first job (at the only animation studio in Grand Rapids, Michigan), my first adult friends, my first girl, and new tastes in music. It also happened to be one of the greatest summers ever for SF and fantasy movies. It was like all the studios somehow knew I would have income and access, so they rolled out their best offerings all at once.

E.T. Wrath of Khan. Tron. Road Warrior. They’ve all settled into their respective vintages since then, but the movie I like most from that summer has proven to be the most enduring and timeless. I think you can guess which one.

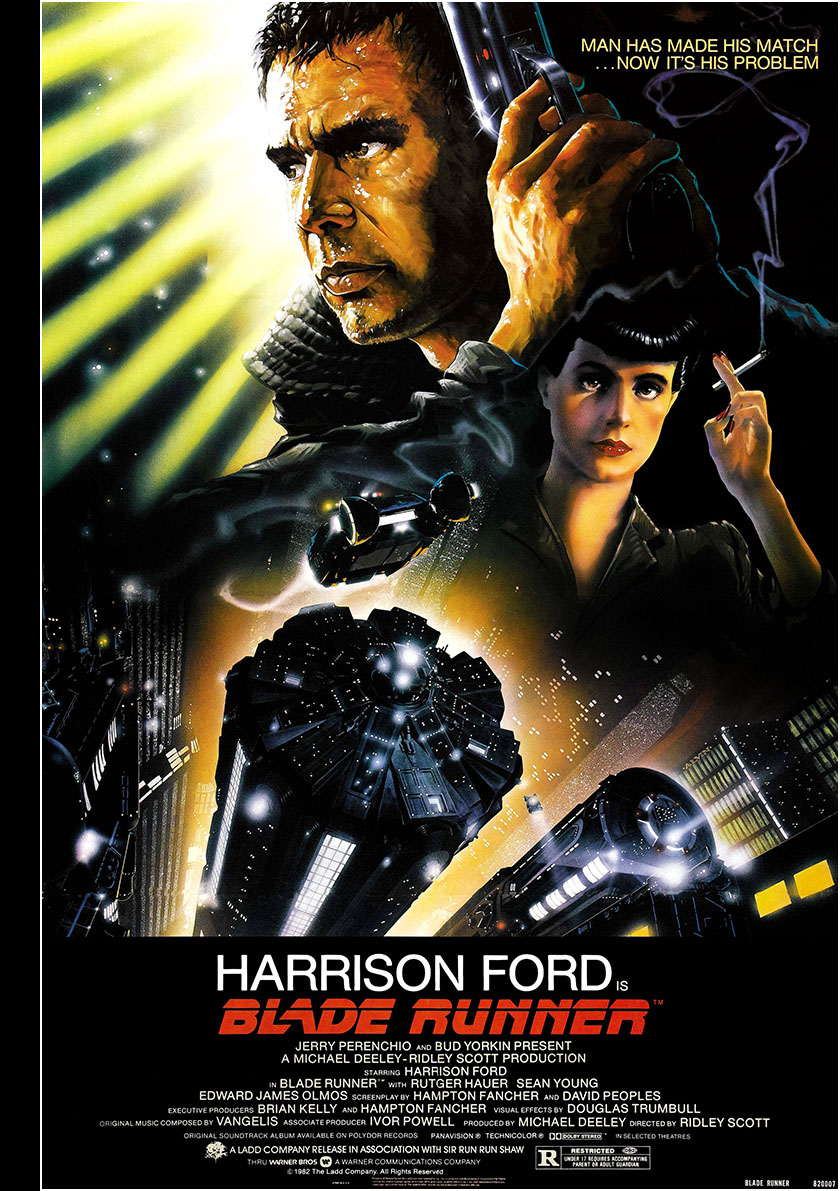

I could feel myself becoming an adult while watching Blade Runner for the first time. By that, I mean the images, themes, and sounds of that film opened me up and matured me in a way no film had done before. It was immersive, seductive, and hypnotic. The outside world ceased to exist for those two hours. It was exactly the experience I was ready for right after turning 17.

After that summer was over, I returned to my crummy high school for my crummy senior year. It felt like being dragged backward downhill. I’d gotten a taste of what was waiting for me on the other side, and I was desperate to return to it. During that time, Blade Runner was one of the things that kept me going. Its theatrical run was over, but I scooped up every book and magazine I could find. Reading and re-reading them kept the experience alive and gave me a future to look forward to.

Marvel Comics was the first out of the chute with their Blade Runner adaptation. I saw the movie right away when it came out (June 25, 1982), but I know for certain I’d read the Marvel adaptation first because it gave me an impression that the movie completely obliterated. The reasons behind this unexpectedly taught me a LOT about the limitations of my future profession.

Naturally, the comic was soundless whereas sound played such a major role in the film that it became a character unto itself.

Secondary to that, a printed-word version of the story was an entirely different experience. Before seeing the film, it was impossible to perceive accents and vocal quality. In the comic, it was as if everyone was speaking in the same voice. And since there wasn’t much physical action, narration played a huge role. I didn’t mind Harrison Ford’s deadpan narration in the movie. In fact, the comic had prepared me for it, so it didn’t feel out of place at all. Writer Archie Goodwin used that narration to carry much of the story that couldn’t be drawn, and also to enhance Deckard’s worldview.

To imagine this difference, what would your impression have been if you heard Harrison Ford say these words at the end?

“Blade Runner. You’re always movin’ on the edge I guess it’s inevitable. Someday you’ll fall. On one side or the other.”

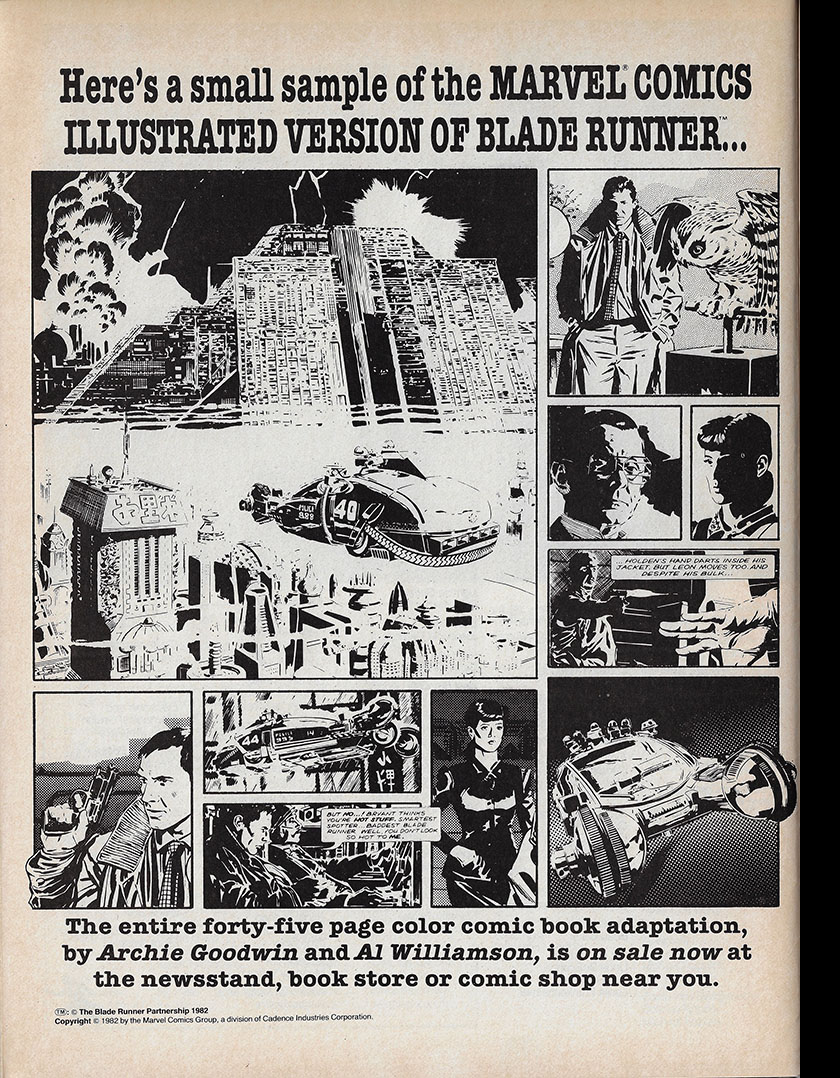

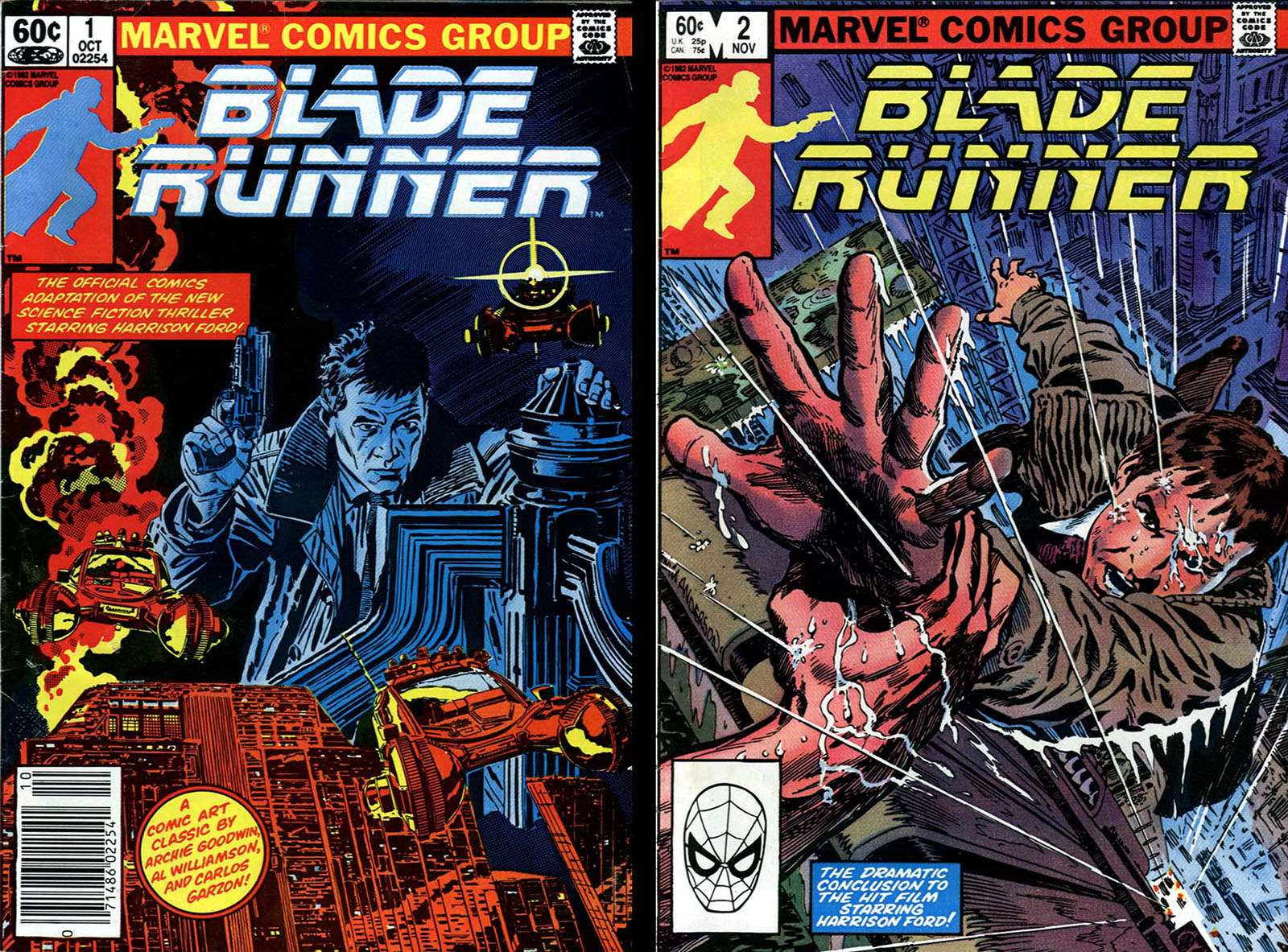

It was the art, though, that made me feel like I couldn’t buy this comic fast enough. Two years earlier, Marvel had introduced me to Al Williamson (and his inker Carlos Garzon) on The Empire Strikes Back. After that I looked everywhere I could for more Al Williamson art, and suddenly here was a fresh helping on a film that held equal interest.

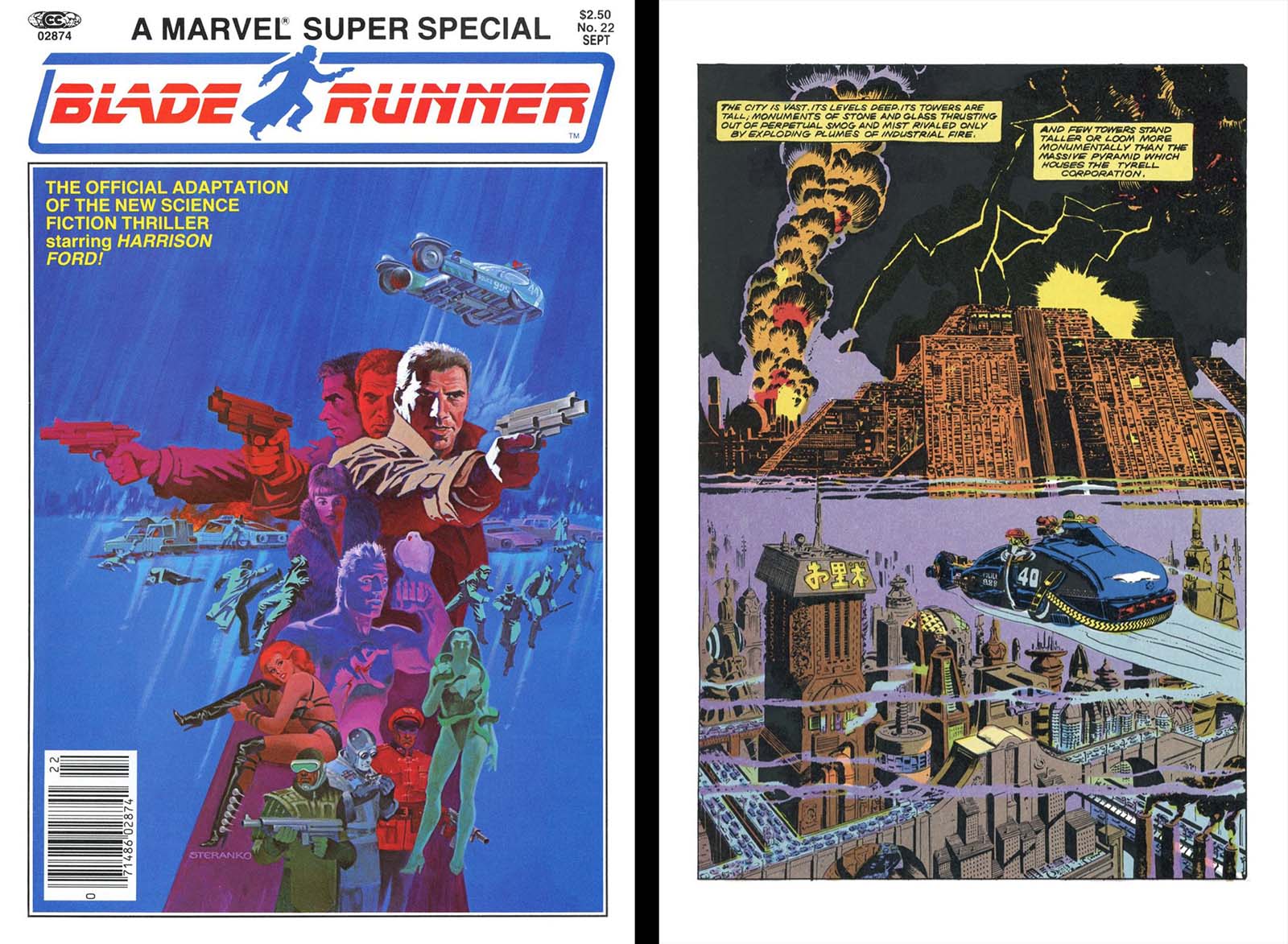

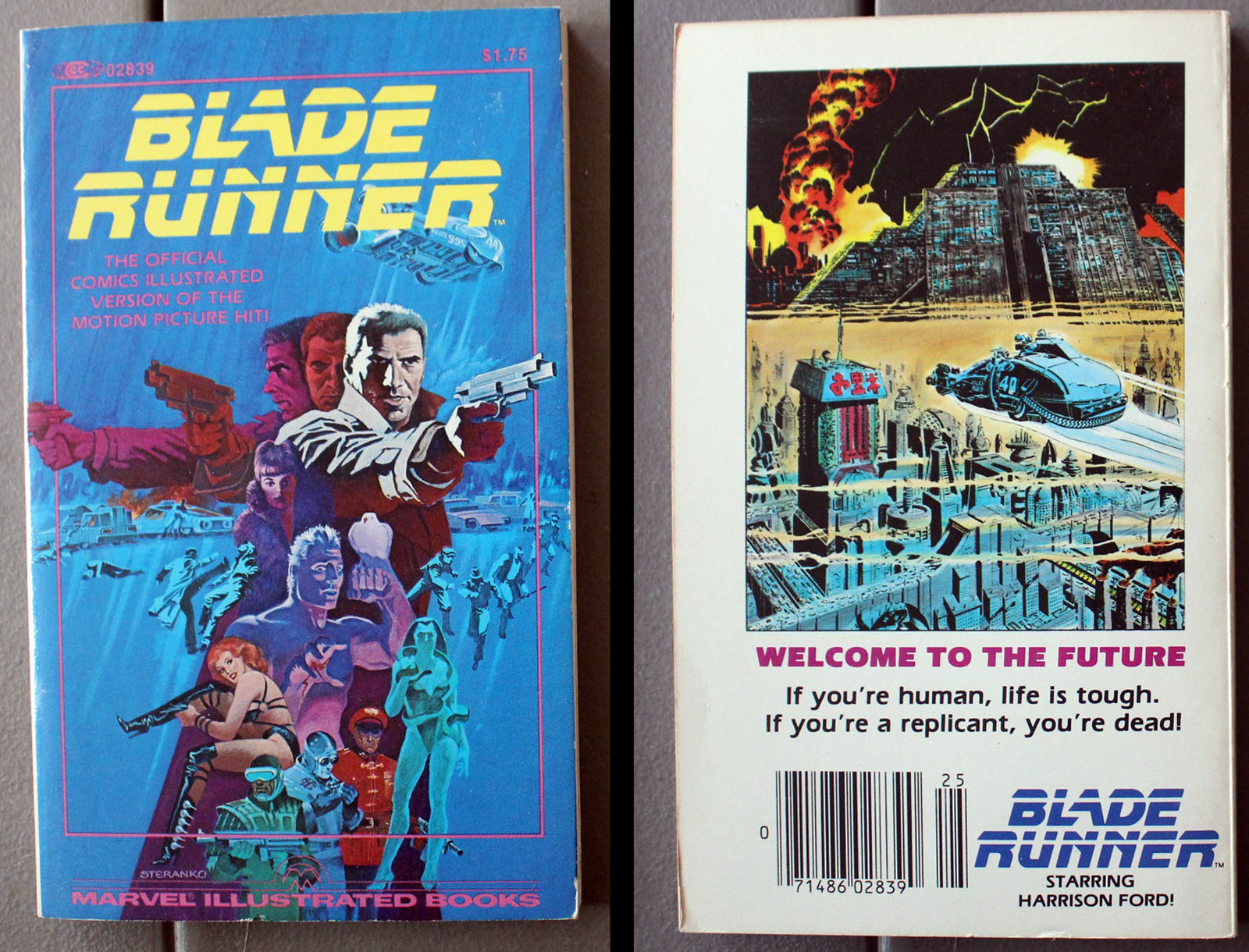

I remember at the time how astonishing it looked. Marvel Super Special No. 22 (dated September, published in June) contained the entire adaptation in one place. It was the length of two regular comics in a single magazine with a glorious Jim Steranko cover and backup articles on the film. I studied every panel, absorbed in the composition and linework. For a time, I thought it was the best film adaptation Marvel had ever done. But again, it could not compare with the film itself. I’m glad I read it first, because in the wake of the film it would have felt inadequate.

Two issue version, published in July and August

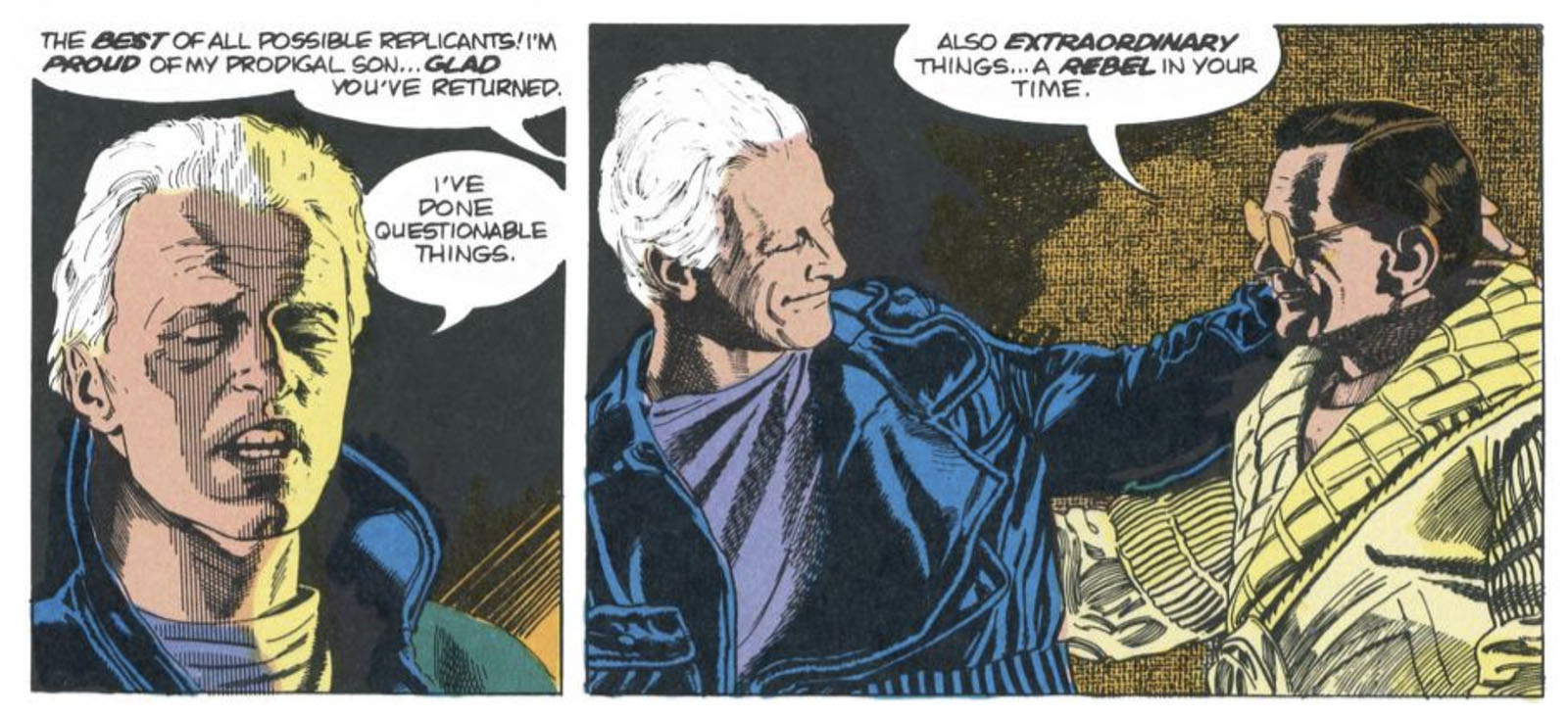

When I look at it today, the artwork is just as lavish and impressive, but now I can see the constraints. It’s almost certain that the creative team must have had a huge pile of stills and a workprint of the film as reference. I don’t think they had a script, or at least a shooting script, because at least one critical line is based on a misunderstanding.

In the comic, Tyrell commends Batty as “a rebel in your time,” whereas in the film he says to “revel in your time.” A mistake like that comes from mishearing a line on tape rather than reading it in a script. This, plus numerous descriptions in the narrative, is why I think a work-in-progress video tape was their primary source.

Also, the vast majority of the panels are so closely based on photo ref that in many cases I could identify exactly which photo or frame of film it came from. This is no slight against Al Williamson; his style was already so photographic that he could move seamlessly in and out of a tracing. However, rather than a story that “flows” on paper, it feels like a series of stills stitched together with narration. It doesn’t do what you want a comic to do. And for that reason, it doesn’t have anything like the dynamism of a film.

Single-volume paperback edition

For this, I have to blame the limited time they had to produce it. It was mentioned in the comic that the whole thing had been drawn in three months, which tells me that’s all the time that was available to them between getting the reference material and meeting the print deadline. Compressing it down to two issues meant they had to tell the story in as few images as possible.

To do justice to the action and cinematography would require at least three issues, more like four. It was possible to make the comic stand on its own two feet and do what comics do well, but it sounds like the time wasn’t available to meet this goal. Regardless, Al Williamson did it his way, and I can’t fault a single drawing in the batch. It was just a case of the finished package not being greater than the sum of its parts.

See all three of the different Marvel editions cover to cover at Archive.org:

Super Special | Issue 1 | Issue 2 | Paperback

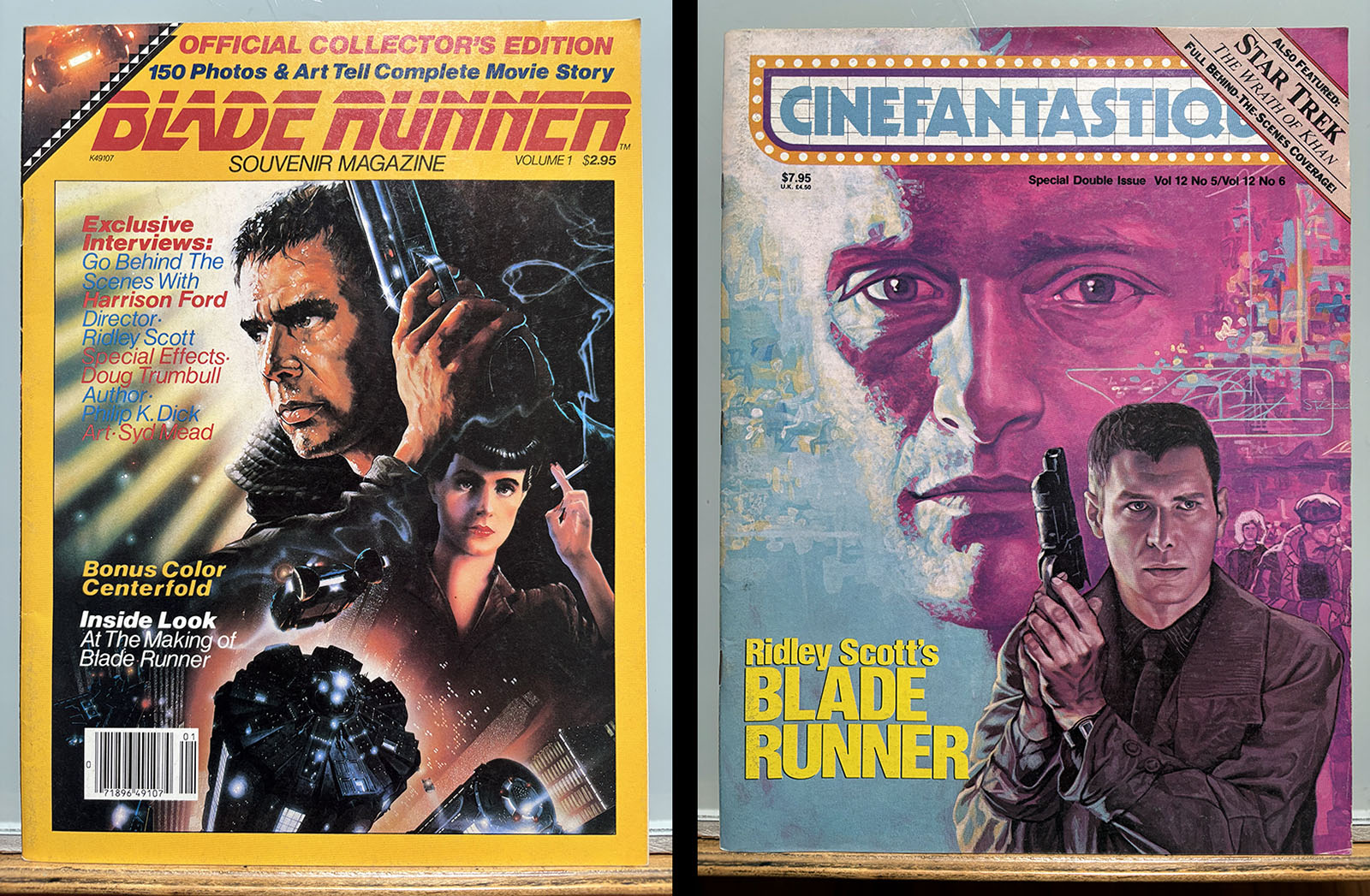

Blade Runner wouldn’t come to home video until 1983 (as the slightly more violent “international cut”), but lucky for me and my fellow media hounds, there was a good amount of published material to fill the gap. Right away, I managed to find the “Souvenir Magazine” and the latest issue of Cinefantastique (Vol. 12) with a hefty cover story. Enough time has passed for both to be posted at Archive.org, so see them for yourself here:

Souvenir Magazine | Cinefantastique Vol. 12

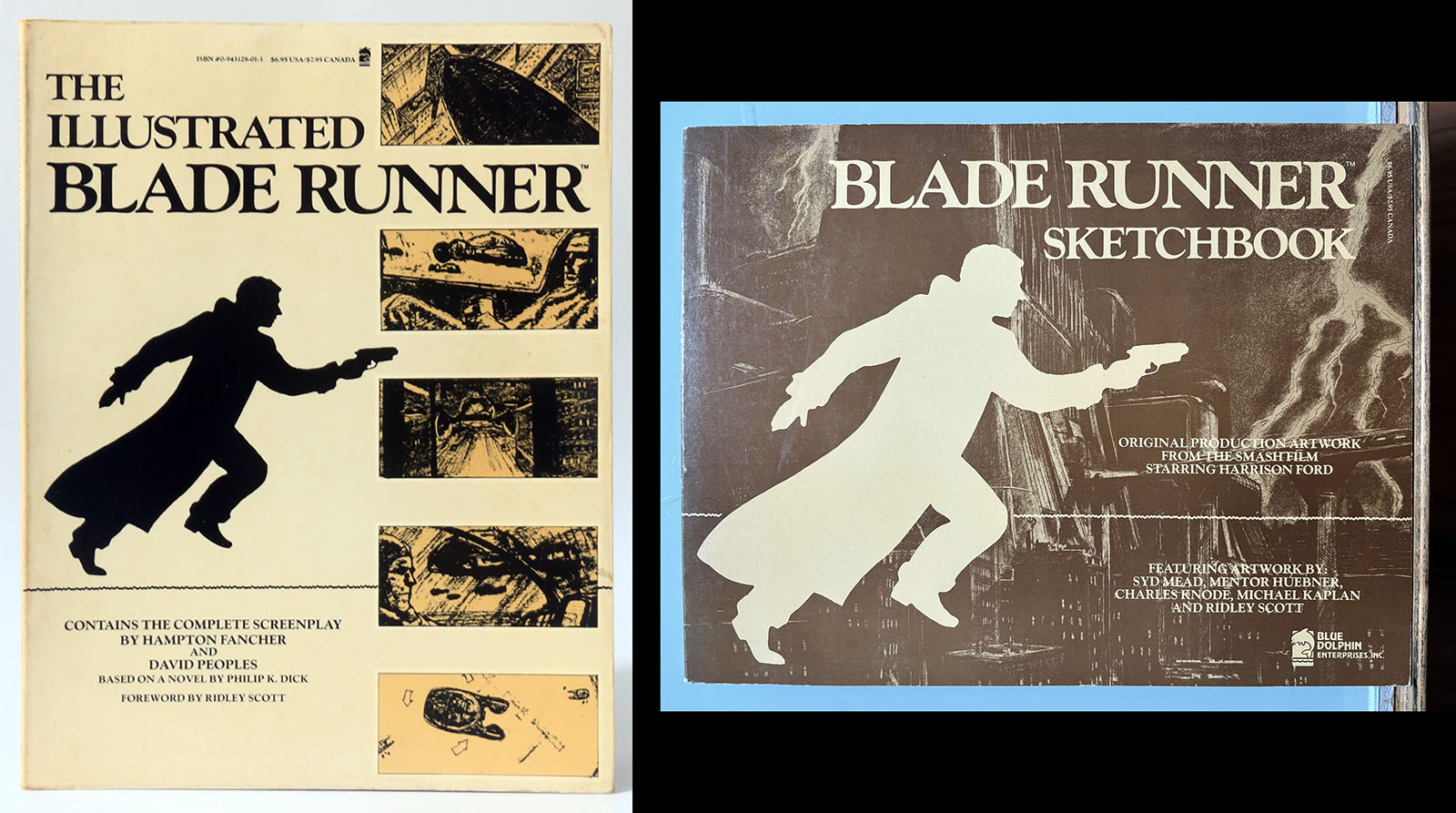

Moving up a notch, there were two high-end books from a publisher named Blue Dolphin: The Illustrated Blade Runner (script and storyboards) and The Blade Runner Sketchbook (production designs). Both followed the tried-and-true publishing formula of Star Wars books and they were much appreciated. See them here:

The Illustrated Blade Runner | Blade Runner sketchbook

Of the more specialized publications, there was Cinefex No. 9. This was a gorgeous magazine with very in-depth coverage and exclusive photos, and Blade Runner filled up this entire issue with stuff that hasn’t been seen since. It also earned a cover story in American Cinematographer, which can be seen here.

If you wanted to relive the story itself, there were two options: Random House published a storybook for young readers, highly sanitized down from an R rating to PG. (See it here.) Then there was a reissue of Philip K. Dick’s novel with a Blade Runner cover that made for an alluring tie-in, but not a great reading experience. I bought it, I read it, and felt no connection beyond the character names.

From across the seas came two collectibles that I managed to scoop up in later years. There was a poster magazine from England and a theatrical program book from Japan. Both had pictures I’d not seen anywhere else, and were highly valued. Especially the Japanese book, which has some great model photography.

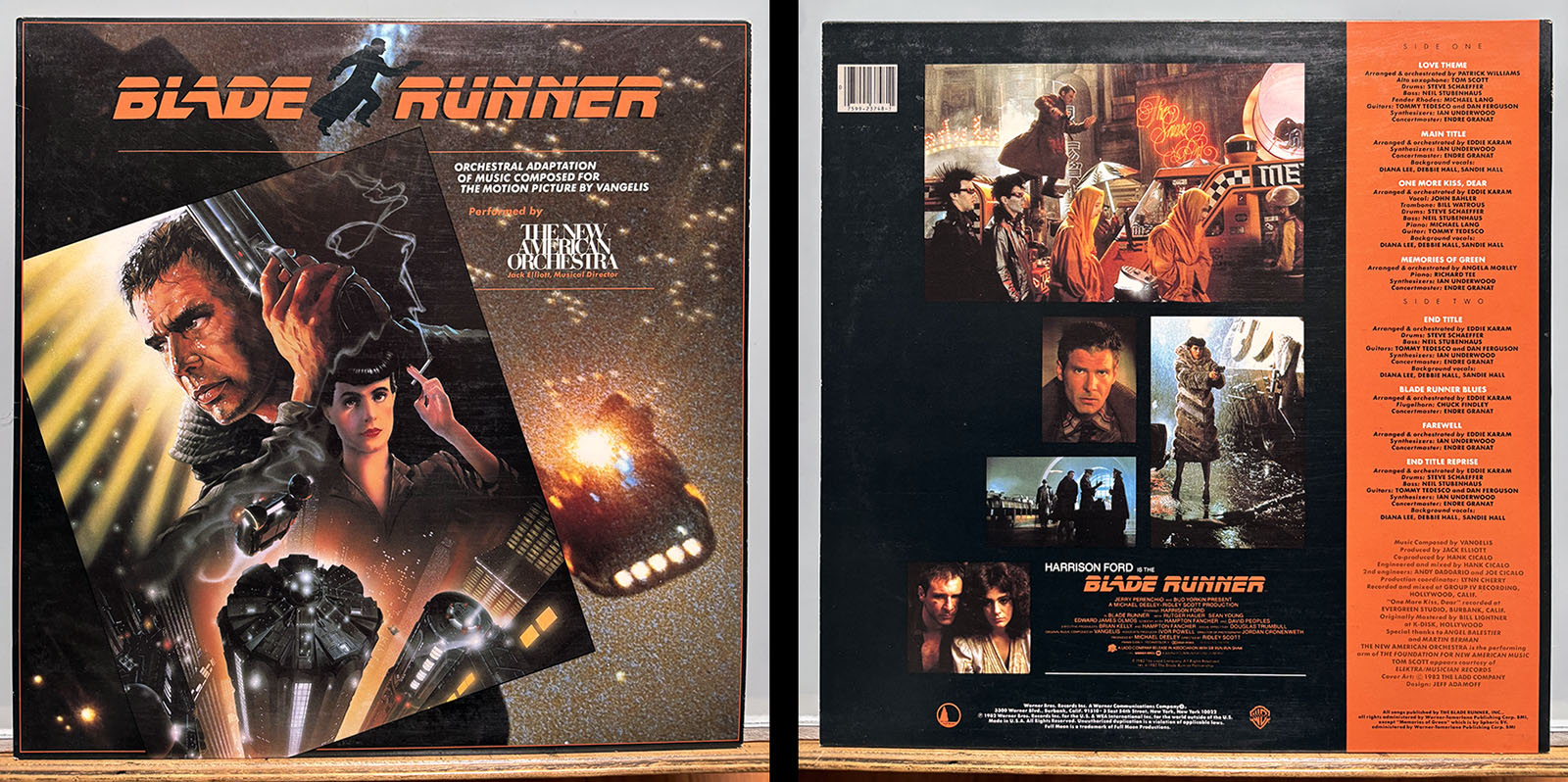

Then there was the haunting musical score, so indelibly fused with the visuals that the world itself became the instrument. The end credits said a soundtrack album was coming (believe me, I looked) but instead we got what was described on its own jacket as an “orchestral adaptation.” I grabbed it, of course, but was under no illusion that this is what I’d heard in the theater. The notes are there, but the scale and intensity are sorely lacking. If Blade Runner had been made for TV, this is probably what the music would have sounded like. But I’m grateful that it was there to help me understand and appreciate the difference.

It took an unbearably long time for this to be rectified. As it turned out, the composer Vangelis was unhappy with how Ridley Scott had edited and altered his work in the final product, so he did not consent to an official release until he could make it his own. That resulted in a 1994 CD from Atlantic (above left) that gave me some of what I was hoping for, but not all of it.

Later I found a 1995 Romanian bootleg (Gongo Music, GM-003). It was EXTREMELY expensive but worth every penny since it added quite a bit to the ’94 CD. Still not everything, though. It was only natural that someone would try to correct the situation. That someone was musician Edgar Rothermich, who painstakingly reconstructed the Vangelis score (which had no sheet music, it should be mentioned) and performed it on the same instruments. This was released in 2014 from BSX Records (BSXCD 9100) and is essentially a cover album of the Romanian version. Other than the bootleg, all the albums shown above can be found on Apple Music. Fortunately, the options don’t end there.

There was also a Blade Runner Trilogy 3-disc set that contained a reissue of the 1994 CD along with extra tracks and “inspired by” music, so if you’re a completist like I am, you’ll want that one, too. On the other hand, “complete” is relative since there are still many pieces not included.

Thankfully, there were fans with the drive and the resources to address this. They spent decades hunting down all the missing pieces, and assembling them into various bootleg compilations (read about them here). Their collective effort culminated in a gloriously complete score that leaves NOTHING out. So clear your schedule and listen to it on Youtube here.

As for home video, the world is our oyster. I’m partial to the “Ultimate Collector’s Edition” (2007), a 5-DVD set in a Voight-Kampff case which has four different versions of the film (up to and including The Final Cut), a ton of deleted/alternate scenes (adding up to a variant version of the whole movie) and lots of making-of material. There’s a 5-disc “Complete Collector’s Edition” Blu-ray set as well, but it doesn’t come with the case or the extra kipple (like the 4″ Spinner miniature).

For safety, I also picked up The Final Cut on Blu-ray (2018) with the same making-of material. And I found a Japanese Blu-ray titled Blade Runner Chronicle which has all three versions prior to The Final Cut.

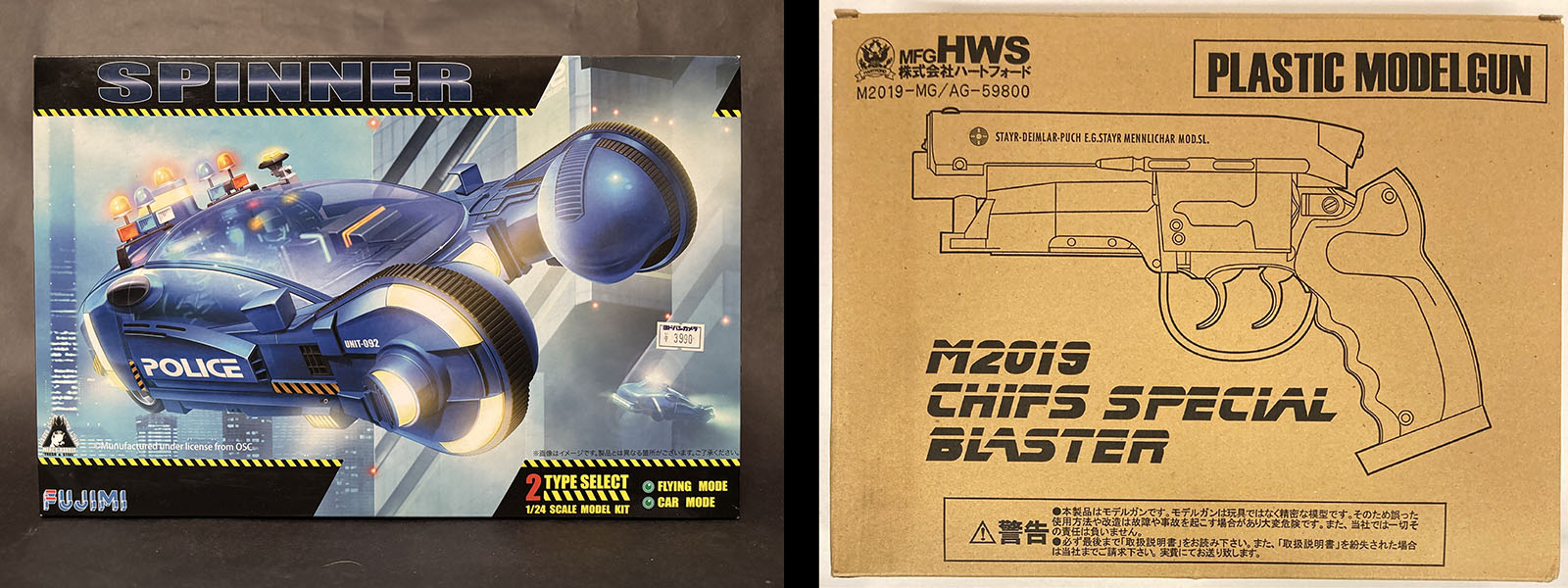

The only toys that were promoted upon release of the film in 1982 were diecast metal cars made by ERTL, a company primarily known for specializing in miniature farm vehicles. They got into the licensing game when they purchased the AMT model kit company in 1981.

Four Blade Runner vehicles went to market, but were gone in a flash (I sure never saw them). Now they’re highly prized as collectibles. Read all about them here.

If you REALLY wanted some prime merch, you had to go to Japan, where almost anything cool gets the attention of artisanal toy makers. The first Japanese Blade Runner goods were unlicensed, limited edition products that filled in the exact niche that went empty in the U.S. Many more have appeared in the decades since.

See a bunch of them in a photo gallery here.

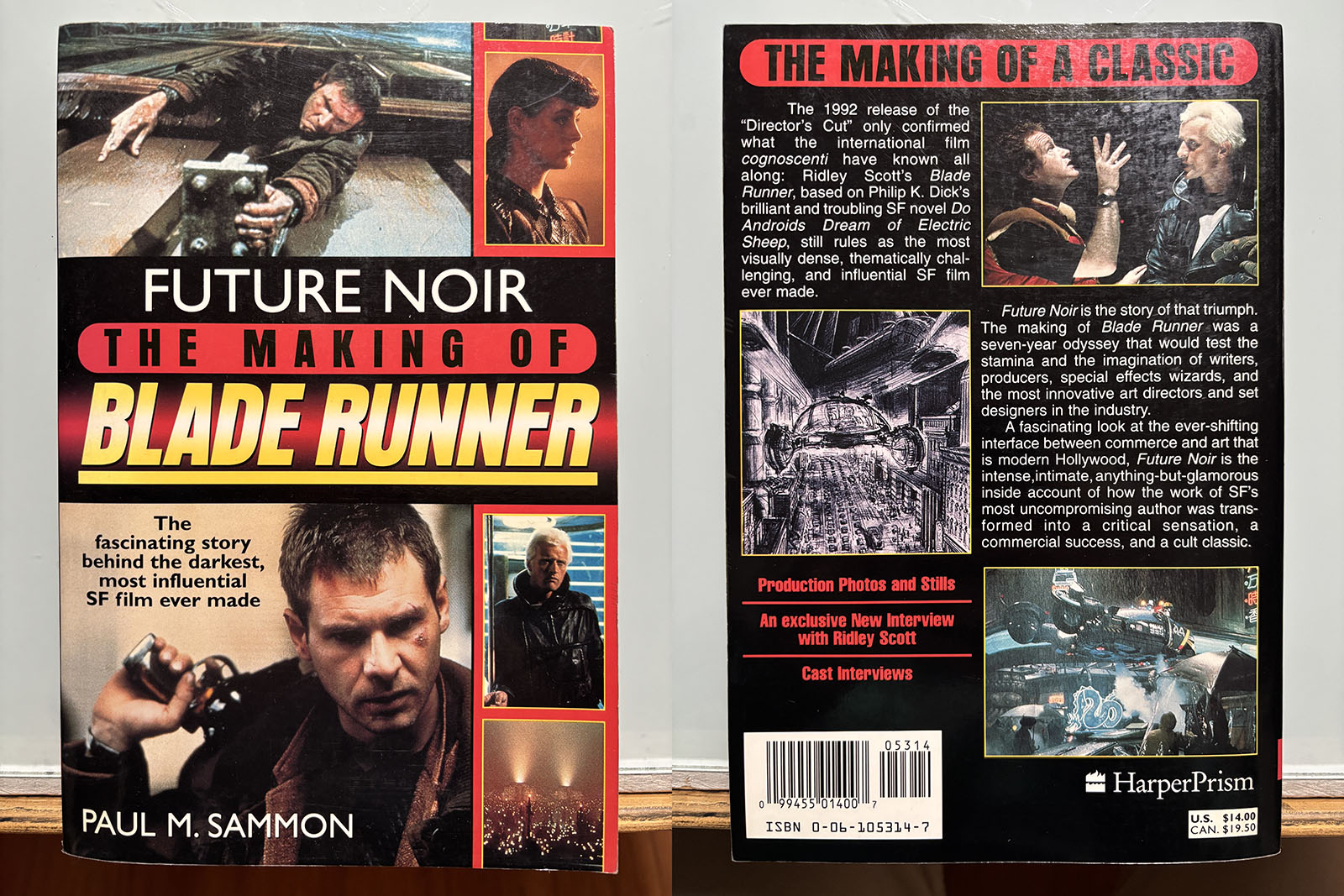

If seeing all this long-out-of-print treasure bums you out, there’s a more recent book to go after. Future Noir is an incredible deep dive into the film, published in 1996. Put it on your hit list!

Then there’s also the Wikipedia page.

I’d throw all this stuff back in time to 17-year-old me if I could, anything to get through that last year of high school, but experiencing it all gradually in real time was a critical part of the process. Studying and meditating on the film, and comparing it to the comic adaptation, was a powerful educational experience that helped shape me into who I am now. As it turns out, you can learn quite a lot on the edge of the blade.

Lucky special bonus #1

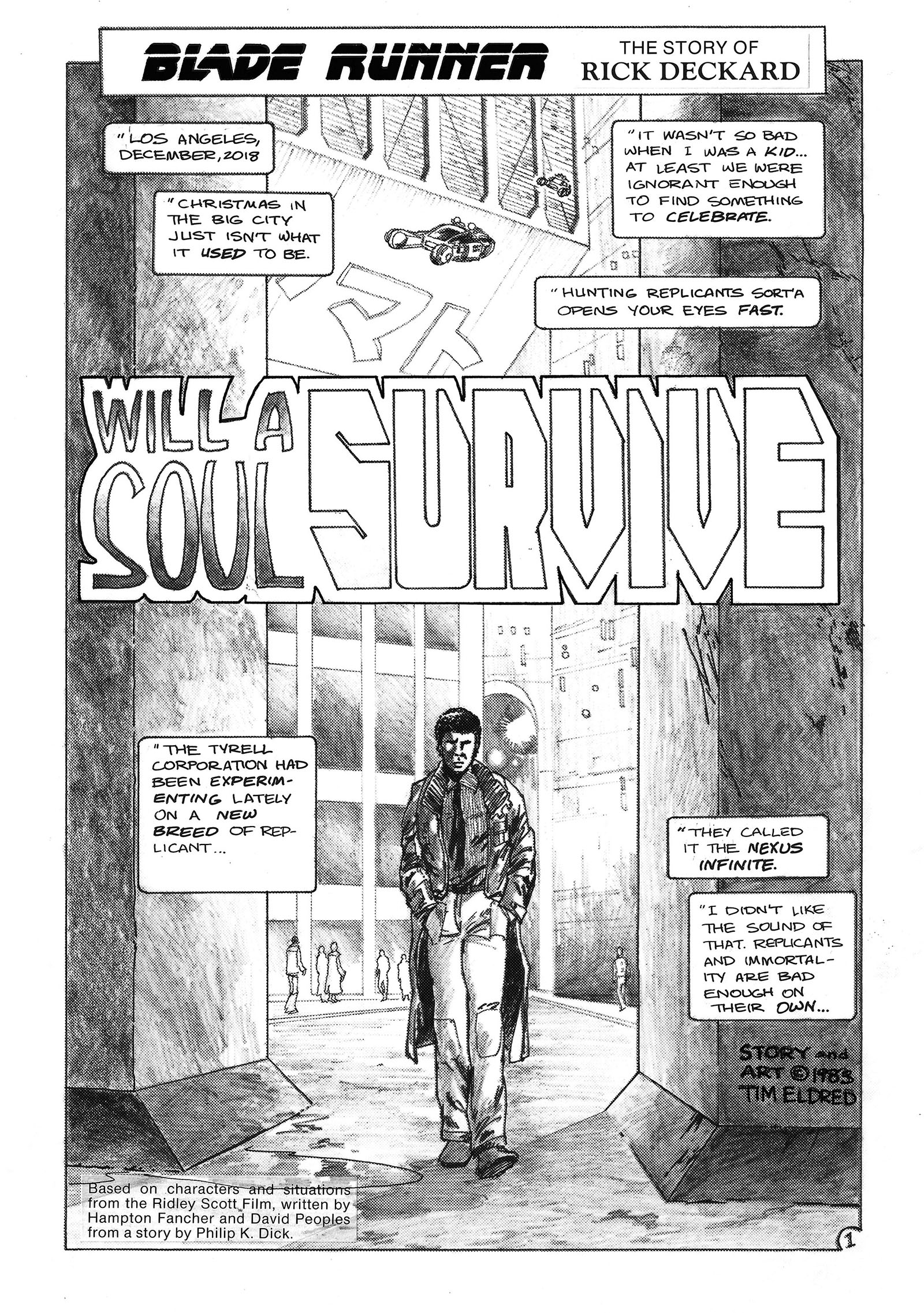

I didn’t just meditate on Blade Runner through my senior year in high school. It had gotten so deep into my bloodstream that it had to come out as a fanzine comic. Click here to read the whole thing…if you dare.

Lucky special bonus #2

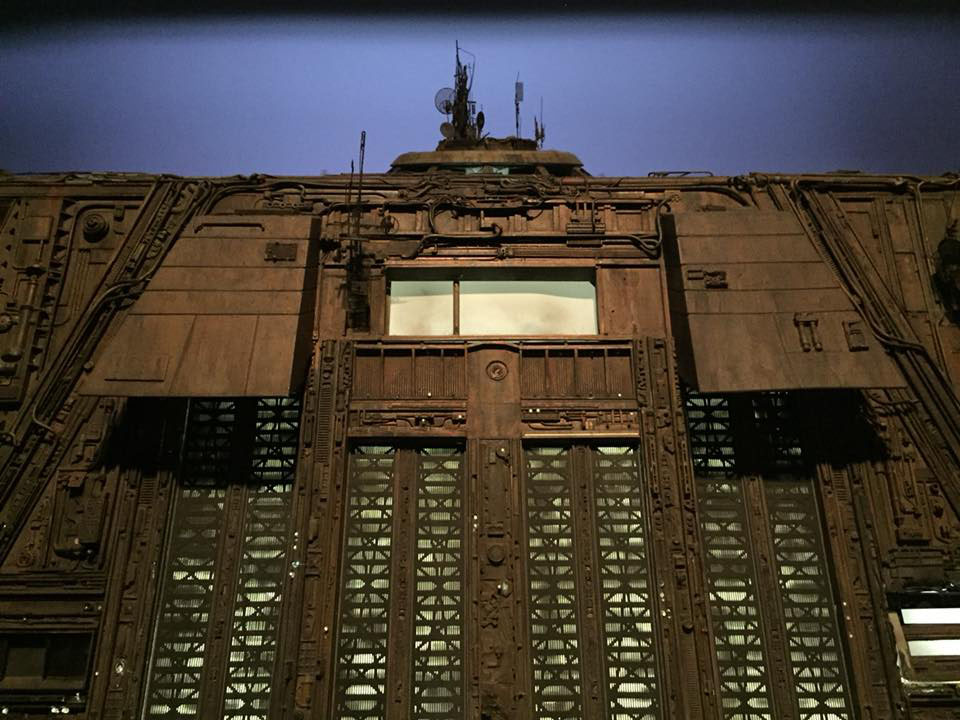

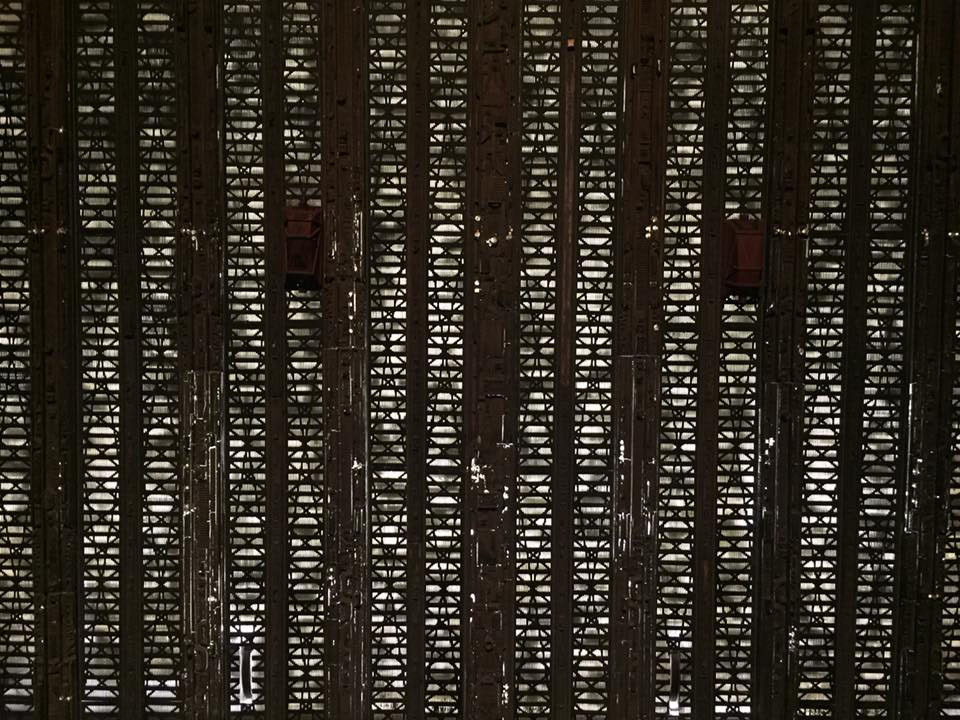

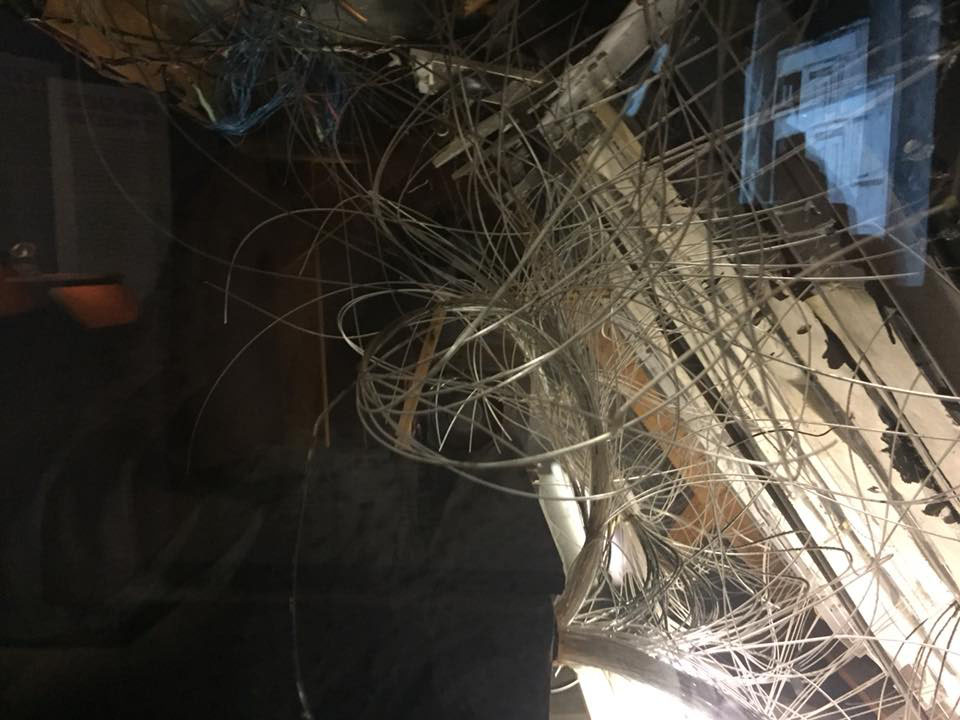

In June 2018, I finally came into personal contact with an artifact from the world of Blade Runner. It was at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York City; on display in a space devoted to film props, there was an intact “hero model” of the Tyrell pyramid, specifically the face of the building that was built for close-up shots of the exterior elevator. The only way I could improve that story is if it happened in November 2019.