Satoshi Chiba interview, 2023

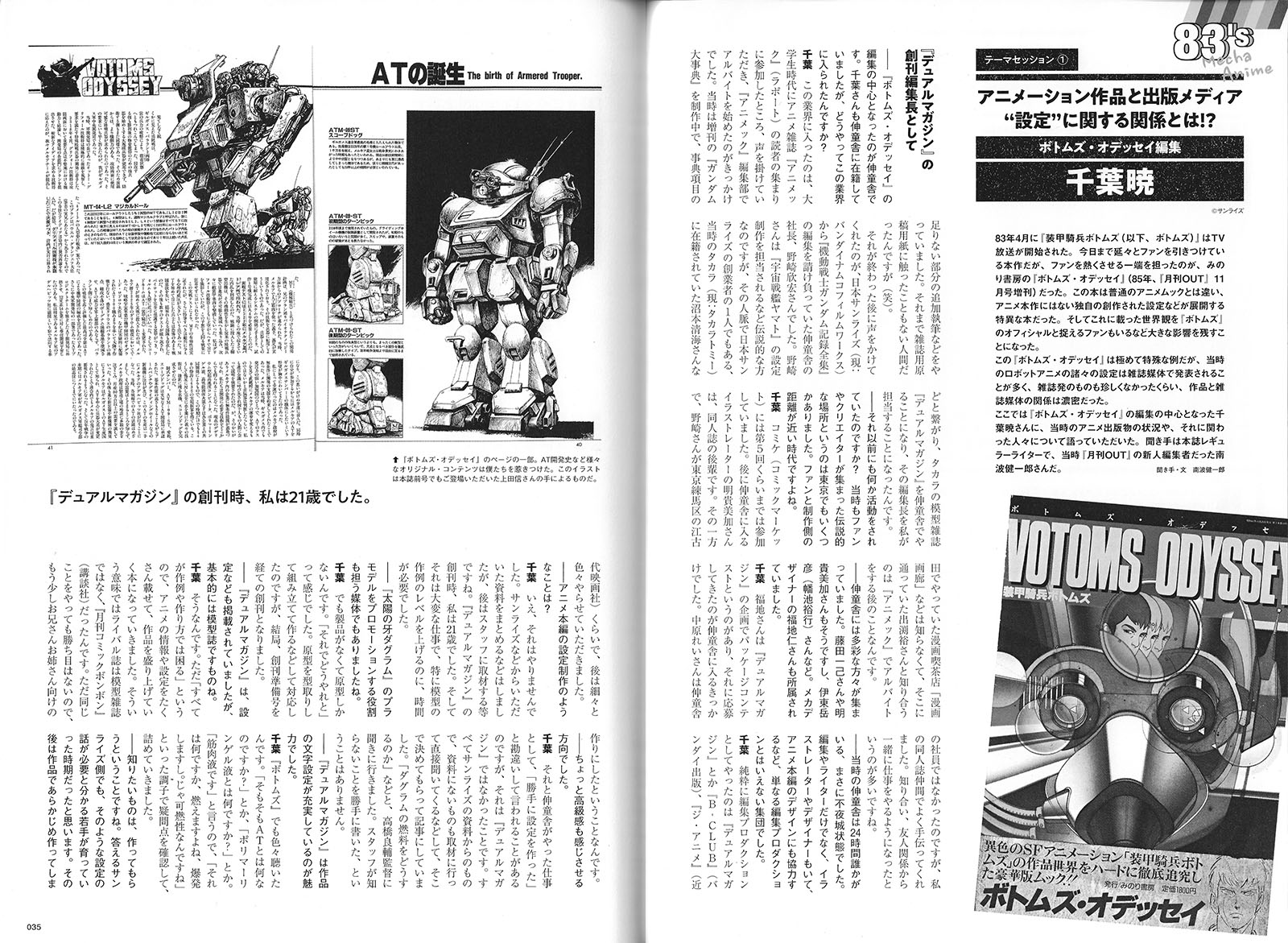

There are many key names to know when reviewing the roster of major contributors to Armored Trooper Votoms, from Creator Ryosuke Takahashi to all the major staff members who worked with him. Then there are those we’re indebted to without even knowing it yet. You’re about to meet one of them.

The most important publishing projects in the early years of Votoms, those that cemented its place in anime history, can be traced back to an editorial production company named Shindosha and an editor named Satoshi Chiba. He is the walking definition of a fan who lived the dream, curating and repackaging information in such a way that it moved the entire body of work forward.

His Votoms projects were Dual Magazine (published by Takara) and Votoms Odyssey (published by Minori Shobo). They expanded the worldview exponentially, energizing the fan base in a feedback loop that motivated Sunrise to produce more Votoms. An individual fan can provide no higher service than that.

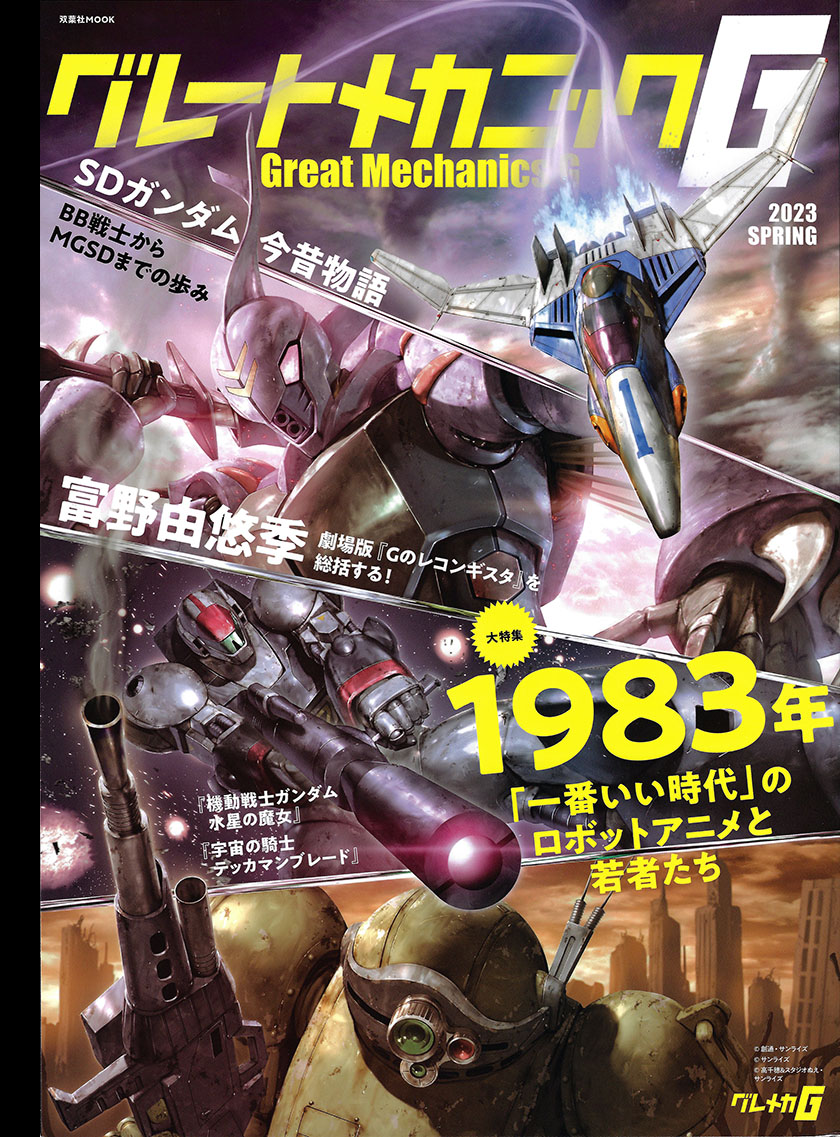

This interview was published in the spring 2023 issue of Great Mechanics G (published by Futabasha). The theme for the issue was 1983, a pivotal year for mecha anime in Japan, and the many industries that spun out of it.

(Order a copy of the magazine here.)

What is the relationship between animation works and publishing media “concepts”?

Votoms Odyssey editor Satoshi Chiba

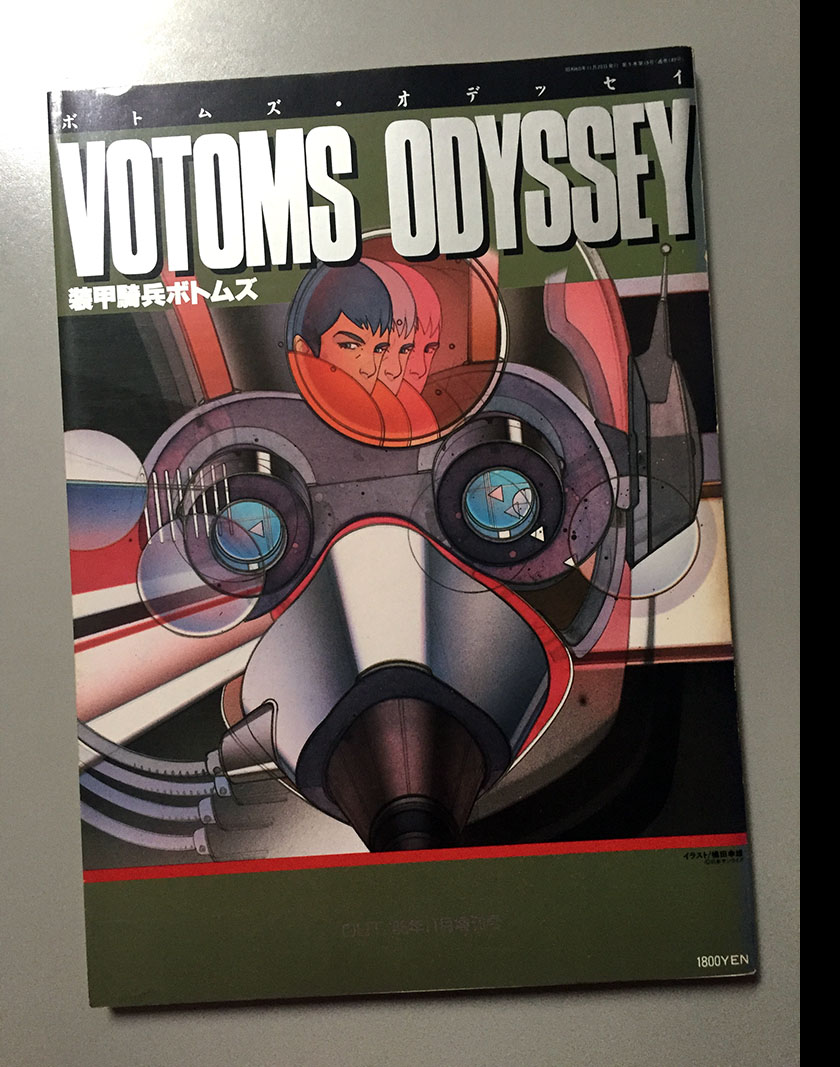

In April 1983, Armored Trooper Votoms was first broadcast on TV. This work has been attracting fans for a long time, and Votoms Odyssey (published in November 1985 as a spinoff of Minori Shobo’s OUT magazine) was one of the books that got fans excited. This book was different from ordinary anime mooks, developing its own original concepts which were not found in The Anime series. It had a great impact on fans, some of whom consider this book to present the official Votoms world.

Votoms Odyssey is a very special case. In those days, robot anime concepts were often published in magazines, creating a strong relationship between the works and the media.

Here, we interview Satoshi Chiba, who played a central role in the editing of Votoms Odyssey. He talked about the state of anime publications at the time and the people involved. The interviewer is Kenichiro Namba, a regular writer for this magazine and a the editor of OUT at the time.

Translation note: I’m interpreting the Japanese word “Settei” as “concept” throughout this interview, but it’s a word that encompasses a lot. It is often translated as “setting,” but it incorporates background, story, and art created for an anime work, which greatly supersedes what we often think of as a “setting.” It can also mean “establishment” or “creation,” so I think “concept” is a fitting word for it.

As the founding editor-in-chiefof Dual Magazine

Namba: You were working for Shindosha, which was the editorial hub for Votoms Odyssey. How did you get into the industry?

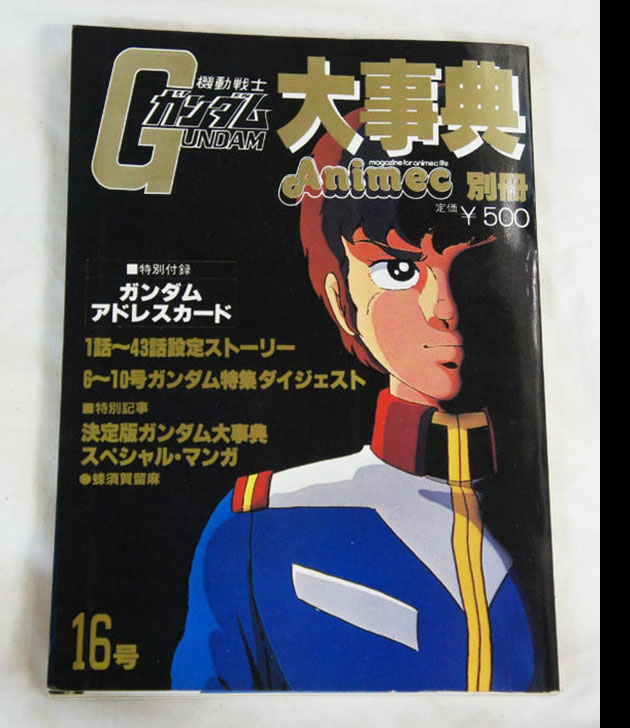

Chiba: I entered the industry when I was a university student. I participated in a meeting of readers of the anime magazine titled Animec (Rapport Publishing), and started working part-time in their editorial department. At the time, we were working on the Gundam Encyclopedia, a spinoff of the magazine, and I wrote additional entries that were missing. I had never even touched a magazine manuscript before. (Laughs)

After that was over, I was approached by Kinhiro Nozaki, the president of Shindosha, which had been contracted by Nippon Sunrise (now Bandai Namco Filmworks) to edit the Complete Mobile Suit Gundam Record Collection. Mr. Nozaki is a legendary figure, having been in charge of design production for Space Battleship Yamato. He was also one of the founders of Nippon Sunrise through his personal connections.

He was connected with Kiyomi Numamoto, who worked for Takara (now Takara Tomy) at the time. I was assigned to be the editor-in-chief of Dual Magazine, a model magazine for Takara, which was produced by Shindosha.

Namba: Were you involved in any activities before that? Even back then, there were some legendary places in Tokyo where fans and creators gathered. It was a time when fans and creators were very close.

Chiba: I participated in Comiket up to about the 5th time. Illustrator Mika Akitaka, who later joined Shindosha, was my doujinshi assistant. [“Doujinshi” is the Japanese word for “fanzine.”] On the other hand, I didn’t know about the manga cafe “Manga Gallery” that Mr. Nozaki ran in Nerima, Tokyo. It wasn’t until after I started working part-time at Animec that I became acquainted with [Director/Designer] Yutaka Izubuchi, who used to go there.

Namba: There was a diverse group of people at Shindosha. [Designers/illustrators] Kazumi Fujita and Mika Akitaka were among them, as was Hiroyuki Hataike. [Real name, Takehiko Ito.] Hitoshi Fukuchi, a mecha designer, was also a member.

Chiba: Mr. Fukuchi entered a “package contest” held by Dual Magazine, and that’s how he got into Shindosha. Rei Nakahara was not an employee of Shindosha, but he was a friend of mine and often helped me with my doujinshi projects. A lot of us started working together because we were acquaintances and friends.

Namba: At that time, Shindosha had someone working 24 hours a day. There were not only editors and writers, but also illustrators and designers. You were more than just an editorial production team. You also collaborated on designs for full-length anime.

Chiba: I did purely editorial production for Dual Magazine and B-Club (Bandai Publishing) and various projects for The Anime magazine (Kindai Eiga-sha) and such.

Namba: Did you do anything like the creation of concepts for anime?

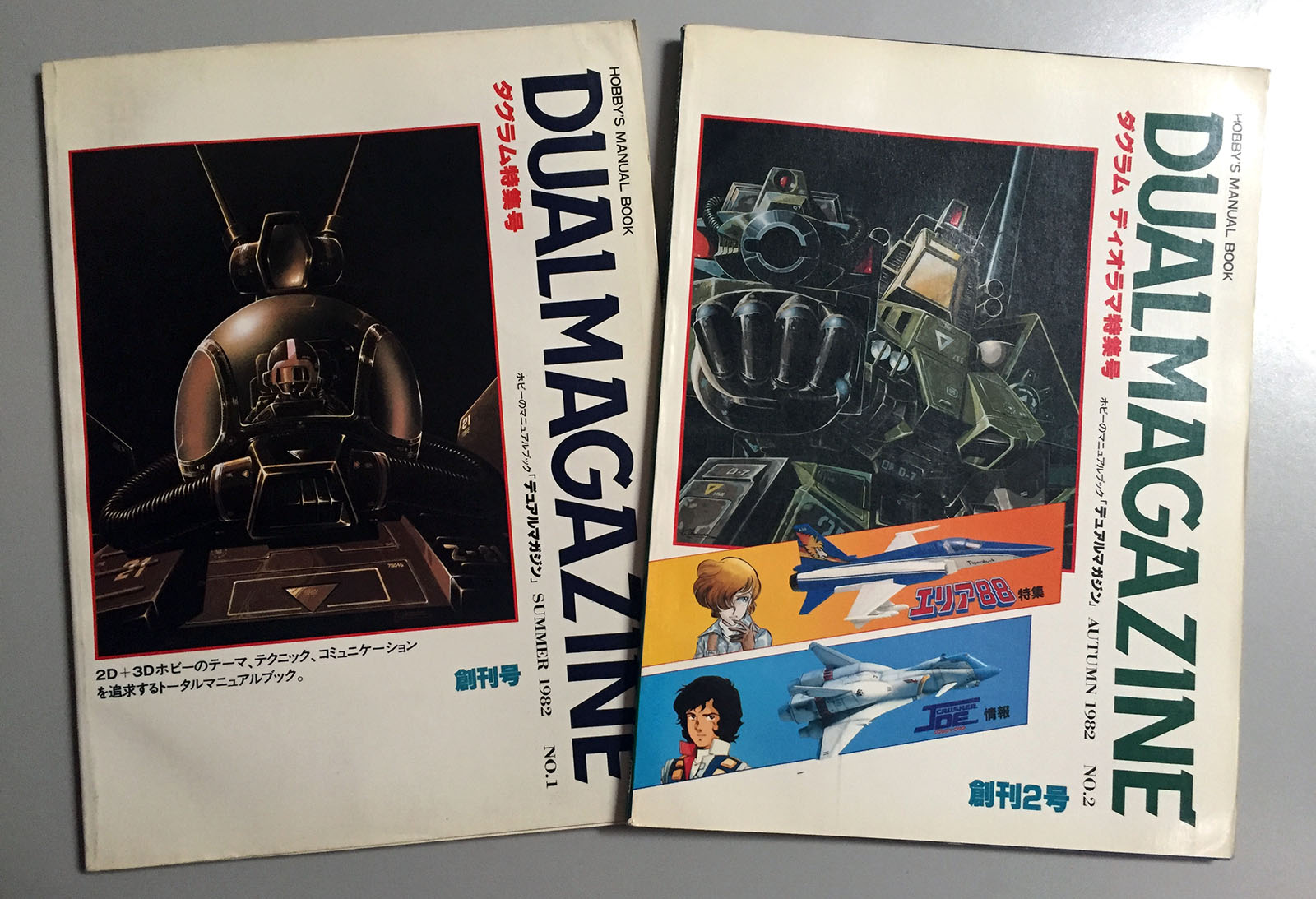

Chiba: No, but I did compile materials I received from Sunrise and other sources. The rest was interviewing staff members and such. I was 21 years old when Dual Magazine was launched. It was a lot of work, and it took time, especially to raise the level of the modeling examples.

The first two issues of Dual Magazine, June and September 1983

Namba: Dual Magazine also played a role in promoting plamodels for Fang of the Sun Dougram, didn’t it?

Chiba: But we didn’t have any products, only prototypes. I was like, “What am I supposed to do with this?” We tried to deal with the situation by making a prototype mold and assembling it, but in the end, we just couldn’t do it. The first issue of the magazine was launched after the first preparatory issue.

Namba: Dual Magazine also included concepts, designs, and other information. It was basically a model magazine, wasn’t it?

Chiba: That’s right. However, we didn’t want to include only examples of how to build them, so we started to include a lot of anime information and designs to enhance the works. In that sense, our rivals weren’t modeling magazines, but a monthly manga magazine called Comic BonBon (Kodansha). If we just did the same thing, we wouldn’t have had a chance, so we decided to make it a little more for older kids.

Namba: That made it feel a little more upscale.

Chiba: As for the work done at Shindosha, it’s sometimes wrongly assumed that I “made up concepts without permission.” But that was not the case with Dual Magazine. It was all from Sunrise’s materials. I would conduct interviews and ask directly about things that were not in the materials, and then wrote articles. I went to Director Ryosuke Takahashi to ask him things like, “What fuel does Dougram run on?” I never wrote anything that didn’t come from the original staff.

Namba: Dual Magazine was attractive to me because of the rich conceptual content.

Chiba: I learned a lot of things about Votoms as well. I asked many questions like, “What is an A.T. in the first place?” or “What is Polymer Ringer Liquid?” I was told, “It’s a muscle fluid.” I said, “What is it? It burns, it explodes. So it’s flammable?” That’s how I questioned things and worked them out.

Namba: You wanted to know how they made it. On the Sunrise side, too, I think it was a time when young people were growing up who understood the need to talk about such concepts. After that, we went in the direction of creating things beforehand in our work.

Chiba: I had been working closely with the people at Sunrise, so my stance was that it would be wrong to create something without permission. On the other hand, Votoms Odyssey was a book made with an open mind. Director Takahashi said, “It’s fine,” so I was able to do it.

Namba: It’s important to have a sense of distance between the work and the staff, isn’t it?

Chiba: I’m not sure what you mean.

Namba: For example, OUT at that time was mostly centered on parody. Because it was a little off the front page, maybe that’s why you were able to publish books like Gundam Century and Votoms Odyssey that featured creative concepts. In other words, it is like an extended version of a doujinshi. In fact, Gundam Century originated as a doujinshi.

Chiba: Votoms Odyssey is not official, but I did visit Sunrise and asked the staff about it. (Laughs)

Namba: As an editor of OUT, I was also a member of the editorial board, and we didn’t think about whether it would become official or not. I think it may have looked more official because we included information about the anime series, and it coincided with the release of the OVA The Last Red Shoulder.

Chiba: I don’t know if that’s good or bad. Ideally, Sunrise would create all the concepts if possible, but if we did that, the staff would get a flat tire. However, the planning office at that time may have done a good job.

Namba: There were times when complaints about articles sometimes went to Sunrise rather than to the publishers. That was a problem even back then. However, no matter how much the magazine said that it was the magazine’s creation, there were still people who complained.

Votoms Odyssey‘s elite lineup of members

Namba: Votoms Odyssey was a conscious deviation from the main anime series from the very beginning. As a result, it grabbed the hearts of Votoms fans, like a powerful drug. Did you plan to do something like that from the start?

Chiba: Yes, I did. We said, “We want to do something military.” But if we did it with Dougram, it would be too close to modern times. On the other hand, I thought it would be difficult to create something new. So we started planning the project by asking ourselves, “How many military elements can we include in Votoms?”

Namba: I think the influence of Votoms Odyssey is why Votoms has become known as “military.” The main anime version has a military atmosphere, but it doesn’t show much of the military itself.

Chiba: That’s right. In fact, it’s not interesting to do military in a proper way in anime. Among them, I think Votoms is a good example of how to incorporate a military atmosphere.

Namba: Votoms captured the hearts of sci-fi fans and movie fans alike. The homages are exquisite, like Blade Runner or 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Chiba: And Apocalypse Now. I think the Kummen arc really defined the military atmosphere of Votoms.

Namba: I think the military image became firmly established through synergy with Votoms Odyssey. The timing of the OVA release two years after the end of the broadcast was also good. How did this book come together?

Chiba: Except for the introduction of the OVA, the illustrations were newly drawn and the articles were created and written as necessary. I was told that I could do as I pleased, so I did. For Dual Magazine, I went to Sunrise to ask questions, but for this book, I couldn’t. I had to ask them to proofread it. The book is said to be “officially unofficial.” But Sunrise’s anime is official, so I couldn’t exclude it.

Namba: Currently, both Votoms and the Gundam series have a large number of fans. But back in the 80’s, probably very few people thought they would still be popular 40 years later. So I think the trend was, “Let’s take advantage of this opportunity and release what we can. Let’s enjoy the work to the fullest, because this may be the last time we see it.” I think the meaning was completely different from the way we see it today.

Chiba: Certainly. In that sense, I think it was a powerful era.

Namba: The staff members who participated in Votoms Odyssey were also very impressive.

Chiba: Makoto Ueda, Jun Suemi, Hiroyuki Hataike, Mika Akitaka, Kazumi Fujita, Mr. Fukuchi, and other illustrators were all distinguished members. I was able to get illustrations by saying, “I want that person to draw this.”

Basically, we emphasized the work and the staff

Namba: After the publication of Votoms Odyssey in 1985, the enthusiasm for robot anime gradually calmed down.

Chiba: Shindosha developed Blue Knight Berserga Story, which was serialized by Masanori Hama in Dual Magazine. It was published in paperback by Asahi Sonorama. After Berserga ended, we launched the table talk RPG Wares Blade and its novels. I think the experience of creating Votoms Odyssey was put to good use on that project.

Namba: What do you think about Votoms Odyssey when you look back on that era?

Chiba: There was a feeling of “We can do anything” at Shindosha at that time. However, there were also restrictions. Basically, we had to focus on the work itself. It meant, “Those who are working on the side shouldn’t make any claims about it.” However, when people who worked on the production staff joined Shindosha in the middle of a project, I think that situation became more ambiguous.

Namba: Everyone was young then, including you. It was a time when there were a lot of chances for young people to thrive. It felt like the adult generation was saying, “New things like anime and games are coming out, and I don’t really understand them, so let’s leave it to the younger generation.”

Chiba: There was certainly a sense of “let the younger generation handle it.” I was young and stood at the center of the production, but even the older generation wasn’t that much older than us.

Namba: When the boom reached its peak, the younger generation who grew up in the boom era entered the anime and publishing industries. Looking back, I feel that 1983 was the watershed year that led to the next era.

See a complete PDF of Votoms Odyssey here

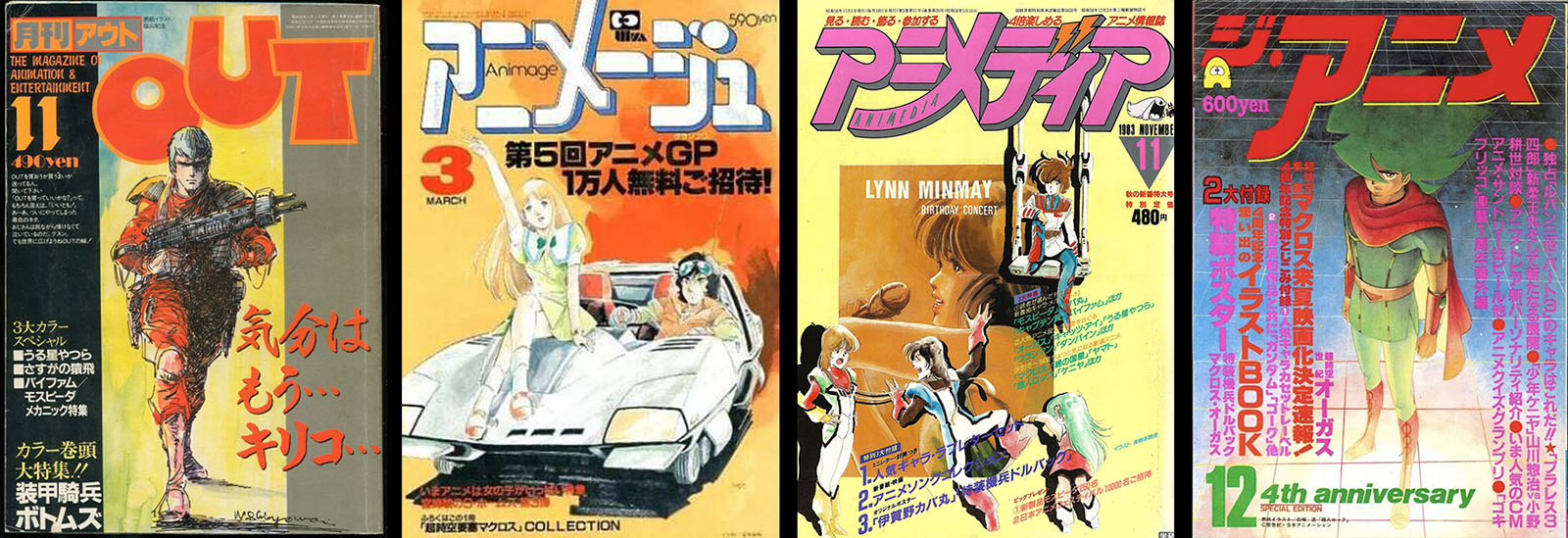

1983 issues of OUT, Animage, Animedia, and The Anime

Sidebar: 1983-84 Anime Magazines

After Space Battleship Yamato in 1974, Mobile Suit Gundam appeared, and the market for anime fan magazines was booming. The first issue of OUT (by Minori Shobo) appeared in 1977, Animage (by Tokuma Shoten) was published in 1978, and by 1983 they were joined by Animedia (Gakken), The Anime (Kindai Eiga) and My Anime (Akita Shoten). In the same year, Rapport’s Animec, which had been published bimonthly, shifted to a monthly magazine from the October issue. Fanroad, the company’s aniparo [anime parody] fan magazine, also became a monthly publication.

Shogakukan published the children’s manga magazine Korokoro Comic and Kodansha published Comic BonBon. These and other manga magazines for children were actively developing anime-related articles and manga adaptations of anime. It was not uncommon for anime to be frequently introduced in other magazines such as weekly shonen manga magazines and movie magazines.

1983 issues of My Anime, Animec, Fanroad, and Comic BonBon

Mobile Suit Gundam became the centerpiece of many anime magazines, but there was no core work to replace it after it ended, which became a cause for concern. In reality, however, there was a shortage of staff due to the publication of spinoff books and other related projects. In fact, each editorial department was looking for new staff.

In the spring of 1984, additional new editors were assigned to each magazine. The atmosphere was very lively, with young editorial reporters gathering to cover new releases and other events. The reality, however, was that as the number of magazines and staff increased, competition for readers intensified behind the scenes. Although the overall audience for anime magazines was on the rise, it was not enough to keep up with the increase in the number of magazines. A few years later, anime magazines ceased publication one after another. It can be said that the seeds had already been sown by then.

Even so, editors and other leaders of anime magazines remained positive. In 1984, the five magazines Animedia, The Anime, My Anime, Animec, and OUT jointly held the Japan Anime Grand Prix. Animage also held its own Anime Grand Prix. The Japan Anime Grand Prix was held in conjunction with the Japan Anime Festival at the Budokan in November 1983. There was a lively and cheerful atmosphere in the anime magazine world from 1983 to 1985.