God’s Child Chapters 1-5

Chapter 1

See the original post here

“Indeed, I promised to raise a child of God…”

Consciousness returned…very slowly. His eyesight returned with it. A blurry, monochrome haze faded and his vision became clearer. He moved his eyes from side to side, but his neck would not budge.

“What is…where is…”

There was nothing noticeable within his range of sight. He perceived what looked like a very drab ceiling and walls.

Eventually, feeling returned to his limbs. Apparently, his body was lying on its side. He tried to move his limbs and raise his body, but he could not get any strength. Not only that, he had the sensation that his whole body was connected to something.

He tried again to look around as much as possible, but nothing came into view. Only metallic, colorless walls and ceiling.

“Looks like you’ve woken up, Chirico. I’m coming now.”

A few minutes after the voice rang out in the room, Chirico was being looked down upon by three men, two in military uniforms and one in white. The man in white took Chirico’s arm, measured his pulse, and examined his eyes.

“He’s in excellent condition.”

“Hmm…”

The two men in uniform looked at Chirico as if he were a rare animal, and then the older man spoke up.

“How are you feeling, Chirico?”

“Do you know me?”

“In a way, you’re kind of famous.”

The other man in uniform said, “You’ve been asleep for almost a month.”

“A month?”

Chirico understood why he had no strength in his limbs.

The next day, he was released from the bed to which he had been strapped. Under the command of the man in the white coat, all the equipment that had been attached to his body, including tubes, wires, and restraint belts, were removed.

The man said, “I am Doctor Godrun Luftienko. I’m responsible for the physical affairs of you and the child.”

Luftienko explained the use of the room and left. What appeared to be just a square metal room had been cleverly designed with a toilet and a table for eating and drinking.

(You said child…you mean the baby.)

Chirico tried to piece together the fragments of his hazy memory and make sense of his present self. But everything was unclear.

(After we escaped from the planet, the newborn baby and I were drifting through space in a green bubble. Somewhere along the way, these guys picked us up. Have I been sleeping for a month?)

Chirico looked around the room, which looked like a square empty can.

A couple of days passed. Chirico’s strength returned to his limbs. Then there came an announcement in the room.

“Chirico, the child wants to see you. We will bring him to you now.”

A few minutes later, the door opened and the three people from the other day came in. They approached Chirico and split to the left and right as if to make way. A boy, who looked to be about five years old, stepped forward and looked up at Chirico.

After a few seconds of staring, he asked, “Are you Chirico?” He had a high-pitched voice that asked decisively.

Chirico’s head was spinning. If these people weren’t lying, it had only been a little over a month.

(If this was the baby I had with me, it should still be an infant…)

However, the boy in front of him was standing on his own feet and speaking. He looked at least five years old.

“I am Chirico, and you are…?”

“I don’t have a name.”

“No name?”

“No.”

“Child is the codename for this project,” the older soldier offered. “We have no authority to give him a name.” There was a hint of awe in his tone.

Doctor Luftienko added more about the child’s growth.

“You slept for four weeks and the child has grown so much in that time. It is unbelievable, but true. A miracle of biology.”

After the doctor’s explanation, the child asked, “Chirico, what are you to me?”

The question was abrupt and mature, but also frank. Chirico hesitated.

“Answer me.”

“We want to know too,” the older soldier urged.

“I only promised…that I would raise you.”

“What do you mean, ‘raise me’?”

“To feed you, teach you things, help you grow.”

“There is no shortage of food,” the child said, looking back at the three men behind him. Then he continued, “I’ve learned many things. I’m growing bigger too. Chirico, how is that different from what you say?”

“I don’t know, maybe it isn’t.”

“How is it different?”

“It’s hard to explain, but I think it is different.”

“That’s unclear. I’m uncertain, explain it properly.”

Chirico fell silent, but the boy asked questions from various angles. His insistence could be seen as childish, despite the clarity of his words. Eventually, as if seeing an opportunity, the older soldier announced, “Tomorrow the child will leave for Melkia. You too, Chirico.”

The other soldier continued, “We’ll be with you. Be ready.”

Chirico was not prepared. Instead, he remembered Wiseman’s words in bits and pieces.

“I had a premonition of the birth of my successor. You will raise my successor. And…revive the system of governance of the Astragius galaxy. I still need you to complement me. I entrust this child with the future of the Astragius Galaxy. Until then, Chirico, you will be the order of the galaxy.”

Chirico took this to heart once again.

(I will keep my promise, Wiseman.)

“Thanks to you, I can leave this frontier planet,” said the younger soldier as they left the room, which still looked like a square monochrome can. “I have you and child to thank for that.”

Three nights after leaving the frontier planet, Chirico received an invitation to dinner from those three men. They were waiting for him in the ship’s main dining room, for the officers.

“I’m more suited to eating rations,” Chirico said, still wearing his fatigues.

“Well, sit down,” the old man said routinely. “We have things to talk about and confirm.”

The meal progressed, and about halfway through, the younger man spoke up, “How’s the food?”

“Not bad.”

“Well, that’s good to know, because it makes it easier to talk, actually.”

The three of them talked about how they wanted to stay involved in the child’s upbringing once they arrived at Melkia.

“Chirico, we need your help.”

“Me?”

“You hold a special place in the child’s heart.”

To summarize the men’s story, the army had declared that the child was the son of God, Wiseman’s successor, and the military believed he would be a force for galactic supremacy. In other words, for the men, being close to the child was a bargaining chip to get ahead.

“We’ll do that when we get to Melkia,” Chirico replied. “By the way, doctor, why don’t you eat?”

Until then, no dinner plate had been brought to the doctor.

“That’s…”

The doctor was about to respond, but a waiter led the child in formal attire into the dining room. Without looking at the others, he took a seat at another table. The doctor got up from his seat. He bowed reverently before the child and took his place at the table.

“I take it you’re accompanying the child?”

Suddenly, emergency lights flashed and an announcement echoed through the ship.

“Balarant fleet approaching! Balarant fleet approaching! All crew to emergency positions!”

How strong was this ship? Was it alone, or part of a fleet? How large was the Balarant fleet? What was their objective? Despite the lack of information, Chirico had only one course of action.

“Come on.”

Chirico grabbed the child’s hand. The doctor stood in the way.

“What are you doing?”

“I don’t think we’re going to Melkia.”

He pushed the doctor aside and hurried into the ship. Vibration and noise told him that a battle had already begun.

“That hurts,” the child shouted. “Let go of my hand!” But Chirico hurried on. His goal was to find a compartment with an escape capsule. He chose one and instructed the boy to “Get in.”

“What about you?”

“I’m with you.”

Would the child understand this?

“Wait!”

The two soldiers caught up with them, the younger one with a pistol in his hand. Chirico did not hesitate. With a flash of his limbs, the two men were on the floor. Chirico kicked away the pistol and shouted, “Stay out of my way!” as he climbed into the capsule.

He pressed the escape button and the capsule automatically began operating. He caught a glance of the doctor as the capsule was instantly ejected, and the two lost consciousness.

The next thing they knew, the surface of the planet was right in front of them. The capsule’s landing controls were working properly, and the parachute deployed. A few minutes later, Chirico and the child were standing on a vast, lichen-covered plain.

(Was this all according to his plan?)

Wiseman must have sent the information about Chirico and the child to the entire Astragius galaxy. As a result of endless, countless, intertwining and conflicting desires, Chirico and the child were led to this planet.

(Wiseman, whatever your intentions, I will keep my promise.)

Chirico thought back again to his reunion with Wiseman on Quent’s twin planet Nullgerant. After thirty years, he too was alive, or rather, reborn. And, as once demanded of Chirico himself, a successor was born as the Child of God. A child of strange abilities, which He entrusted Chirico to raise. It took one with supernatural powers to raise another with supernatural powers.

(Wiseman, I wonder if I can live up to your expectations…)

Chirico checked the emergency kit in the capsule. One automatic rifle, a week’s worth of food and water for one person, some medical supplies, and fuel.

“We have to do something about this,” Chirico said as he looked at the capsule.

Chapter 2

See the original post here

Chirico spent nearly half a day observing the area. The sun didn’t go down even after the time it should have. That meant this was high latitude.

(I don’t know if it’s south or north, but this is a polar circle. Fortunately, it’s summer.)

But as far as the eye could see, there were no trees on the land, only short shrubs here and there. The damp soil was covered with scrubby, unidentifiable grass and lichen.

(Now what to do?)

Chirico looked at the life-saving capsule beside him. He knew that he was in the polar region and that it was summer, but he had no idea what else to expect. Was there any dangerous wildlife?

(I’ll take care of him for two days. After that, I have to do something…)

The capsule would be the marker for a military search, whether it was Gilgamesh or Balarant, but Chirico calculated that it was still safe. It would not be comfortable, but it would protect them from unexpected threats.

“Let’s turn in.”

The sun was still shining, a dull light parallel to the earth, that passed for night here. Chirico urged the child into the capsule.

The next morning, the sun, which never set, was in the opposite position.

“Eat.”

Chirico offered the child an emergency ration he had prepared. The child glanced at the food, but did not reach for it and looked away with a blank expression. Apparently, he didn’t recognize it as food for a child.

“You don’t have to eat if you don’t want to.”

Chirico carefully put away the precious meal. After finishing his own, he suited up.

“Help me,” he prompted.

“With what?”

“To look for cracks in the earth.”

“Why?”

“To hide the capsule.”

“Why?”

“Well, this ground has permafrost. It goes dozens or hundreds of meters below the surface. You can’t dig through it by hand. But there are cracks. In the summer, the cracks thaw. We have to find one that’s big enough to hide the capsule.”

“Why hide the capsule?”

“I don’t have time to explain it to you right now. If you don’t want to help, stay here inside the capsule.”

Chirico started to walk away. He searched the area around the capsule until noon, but could not find a melted crack. He went back to get lunch and offered it to the child, but the boy still would not reach for it. Instead, he repeated the question, “Why hide the capsule?”

“I don’t want them to find it.”

“Them?”

“Gilgamesh and Balarant.”

“Why?”

“It’s a long story. Enough.”

That afternoon, Chirico decided to extend the search to the limits of the capsule’s mobility.

“Stay here. If you see anything, get in the capsule, okay?”

Chirico went back to searching for a crack, but he couldn’t find one.

(If we extend the range any further, we won’t be able to move the capsule.)

He gave up and went back.

“Hmm?”

The child was gone. Something ominous ran through his chest. He tried to call out the child’s name, but no name came out.

“Damn!”

He fired a shot into the sky. The dry gunshot echoed through the wilderness. Then he saw something moving in the distance. It soon became a shadow and then the child.

“Don’t go off alone.”

“I found the melted crack you speak of.”

“Where is it?”

The child pointed backward.

“Lead the way.”

The crack was large enough to conceal the capsule.

“You did it!”

The compliment elicited no response from the child.

“Help me.”

Chirico set about moving the capsule. Even though it was lightweight, it was still work. He got no help from the child.

(Well…)

After hiding the capsule, he set up a tent with a resin pole and parachute cloth from the emergency kit without taking a rest. Although the tent was small, he could stretch out his arms and legs inside it, unlike the capsule. The exhaustion of the labor made him fall asleep at once.

When Chirico woke up the next morning, the child was gone. After preparing breakfast and waiting for a while, he came back.

Then, out of the blue, he said, “I found three cracks.”

“I see. But we don’t need any more.”

The boy’s eyes clouded a little.

“Eat your meal.”

But he only looked away toward the horizon without accepting the plate.

“Why did you go looking for a crack? Do you like cracks?”

It was a strange question, but the answer was also strange.

“This ground has permafrost. It goes dozens or hundreds of meters below the surface. You can’t dig through it by hand. But there are cracks. In the summer, the cracks thaw. We can hide the capsule.”

“The capsule is hidden. So a crack is no longer needed. Now eat your meal.”

There was no response. Chirico suddenly realized something.

“This meal is certainly different from what you’ve been eating. It may not look like food, but it is. There are various kinds of food. Some are good, some are bad. But we have to eat something to survive. First of all, you must be hungry.”

He knew the child was listening, so he continued.

“Anything tastes good when you’re hungry. Besides, it has nutrition. Nutrition is something the human body needs.

The child was definitely listening, and became quite enthusiastic.

“Nutrition has two main roles. One is to build the body, and the other is to provide energy to move the body. This meal is mainly for energy to move the body. So eat up.”

The child’s hand reached for the plate Chirico was offering.

“Eat it, you’ll get stronger.”

The child slowly put something in his mouth that he had never recognized as food before. Then he took down the rest in a single gulp. It was not surprising, since he hadn’t eaten for nearly two days. Chirico realized that if he didn’t explain it properly, this wouldn’t have worked.

“How’s it taste?”

He could readily see the answer in the boy’s eyes; it was good.

“Want some more?”

The clever face nodded vigorously. They finished their meal.

“Now…” Chirico stood up for what he had to do that day.

“Oh, before that…”

He looked at the child. The child looked back. There was an air of something special happening between them.

Chirico said, “If you don’t like it, say no. But from now on, I’ll call you Lu.”

“Lu?”

“Yes, that’s your name.”

“Why Lu?”

“It doesn’t mean anything. I thought about ‘Ah,’ or ‘Ka’ or ‘Tu,’ and I thought Lu would be better. Lu, isn’t that good? I like it.”

The child looked a little thoughtful, then said, “I don’t see a problem. If it’s okay with you, I’ll be Lu from now on.”

Thus, the child became Lu.

Chapter 3

See the original post here

Chirico stood up with his gun.

“Lu. Follow me.”

“Why?”

“We need to know our way around here.”

“Why?”

“To survive.”

“Why do I have to go?”

“I can’t leave you alone.”

“Why not?”

“I can’t protect you if you’re not with me. You’re not strong enough.”

The child appeared to think for a moment, then stood up. The two of them walked in a spiral with a radius of about five kilometers around the tent and searched everywhere. There was nothing but a river in the southeast direction that looked like an ocean. The other side of the river could not be seen. However, it was composed of fresh water, proof that it was not the sea.

“Let’s move closer to that river.”

“Why?”

“Hmph. Asking why again?”

“Why?”

“First, water. Then trees.”

They needed water to survive. There was water in the melting cracks, but the turbidity made it unsuitable for drinking. Driftwood was abundant in the river. Humans need fire. Fire was what separated humans from the wild. Fire was essential for life and safety.

“I understand.”

It wasn’t easy to get the child, Lu, to say these words. He did not tolerate ambiguity, either in words or actions. Chirico and Lu moved the tent near the river later that day. They pitched it a few meters above the surface of the river in case of rain.

“We only have two days of food left.”

The permafrost tundra had no plants or grains to provide food for humans. All they could do was hunt the animals that lived here and fish the rivers. However, they had no idea what kind of fish lived in the rivers, and had no fishing gear or nets.

“There must be something out there, even in this rough terrain.”

In the past three days of searching, they had found several droppings, large and small. Hunting whatever left them seemed most efficient. The size of the droppings and their contents suggested a fairly large herbivore.

“We’ll look for it.”

A kabu was a horned, hoofed mammal that was common in this part of the galaxy.

“How do we find it?”

“We’ll have to walk around.”

“Inefficient.”

“Efficiency? Hmm.”

Chirico laughed at Lu’s words. It was certainly not efficient, but not even Chirico could come up with what Lu called an efficient move.

Two days passed quickly. They saw no sign of prey, but instead discovered a new threat.

“This is…”

The discovery was scattered animal bones. They were picked clean, and the white fragments bore the imprint of sharp fangs.

“It was an urgun.”

“Urgun?”

This was a canine predator that stood at the top of the food chain in northern lands. An adult could weigh as much as a human male. They hunted in packs of about ten that worked in tandem.

“Wait a minute.”

Chirico studied the white fragments more closely.

“There’s also a grantsua.”

“Grantsua?”

A subspecies of brown bear, omnivorous, with males weighing up to 600 kilograms. The white fragments that lost their original shape had been crushed by a grantsua’s powerful jaws. Moreover, the bones looked as if they had been sucked dry, suggesting that there was not much prey for the grantsua.

“Let’s get back to the tent.”

Chirico quickly set to work building a homemade detector. Made of driftwood branches, it was rigged to detect anything that passed through it. He set it up in various key points.

“We’re strangers to urgun and to grantsua, but eventually they’ll perceive us as kabu.”

“One of these days they’ll want to eat us.”

“Ha ha, that’s how it is.”

Lu’s serious face was funny. In Lu’s experience, urgun, grantsua, and kabu were only recognized in relation to food.

“We’ll wait for them.”

Chirico told Lu his plan. Wild animals have a keen sense of smell. They had spent a lot of time in the area over the past few days. In other words, they’d left more than enough traces of themselves. The animals were probably already aware of them.

“So,” Chirico said, glancing at the gun beside him, “we just have to wait and see.”

A day passed. They stayed close to the tent and looked around, but didn’t see anything moving. The next morning, there were traces of an intruder on the farthest detector, but the resilient summer grass had covered the footprints.

“Urgun, grantsua, or kabu?”

Another day passed. Nothing happened. Chirico decided it was time to take the initiative. The next afternoon, he had Lu stand a hundred meters from the tent, waiting for a breeze from the river.

“Are you coming to eat?” Lu called out to the wild.

“Are you scared?” Chirico asked.

“No.”

Lu’s face showed not a trace of fear.

“Tell me if that changes.”

Chirico stood in front of the tent with his gun. The area was clear. He could handle an attack by urgun or the appearance of a grantsua. But nothing moved that day. Chirico looked at the sky above the wide river. A white bird flew overhead.

(I’ll have to shoot one of those when the time comes.)

But he would not be satisfied with the quantity of bird meat. The cost balance of a limited number of bullets and bird meat was not worth it, considering what was to come. Two more days went by, but still nothing promising appeared. The food supply was running out.

“We’ll have to change the plan.”

Lu muttered to no one in particular, “I’ve endured hunger for two days. This is hard.”

He stood in place at the appointed time. Chirico was also in place, gun at the ready.

Soon…it appeared. A shadow approached from the distance, closer and closer.

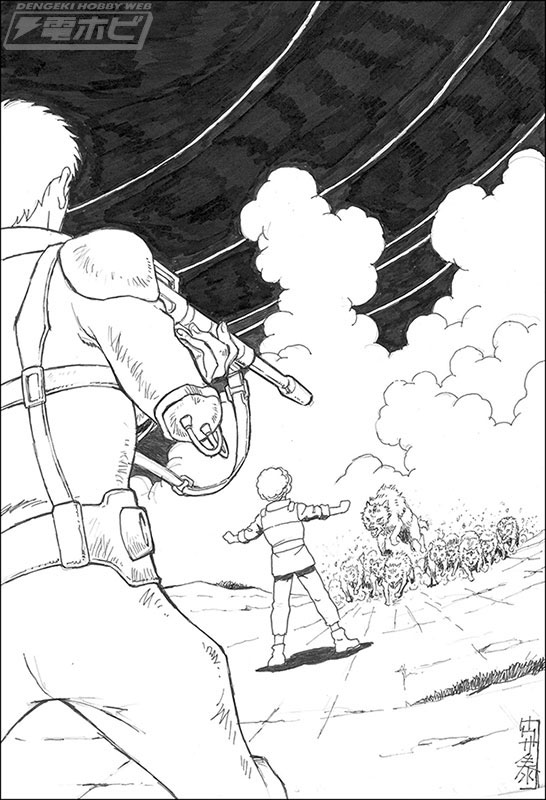

“Urguns. Seven, eight, nine…”

Lu stood there, his face raised in agitation.

“Lu, don’t move!”

Chirico raised his gun. He was confident in his marksmanship, but he decided to fire when they were fifty meters in front of Lu. The pack of urguns approached relentlessly. It must have taken them several days to make this decision. There was no hesitation in their steps. All they had to do was follow their experience and their instincts.

(I’ll take out the pack leader with one shot.)

Chirico had no hesitation either. The speed of the pack increased, and the speed of the leader increased even more.

(Ten meters to go)

Chirico’s finger was on the trigger. At that moment, something unexpected happened.

“Hm?”

Something exploded right in front of the lead urgun. One of the others jumped around as if struck by something. Then another explosion, at the rear of the pack. The urguns stopped, their bodies shaking with the pain of something unbearable. Then, with a cry, they broke off into the direction from which they had come.

“Lu!”

Chirico ran toward Lu.

“Are you okay?”

Lu, as expected, ran up to him and grabbed him by the shoulders.

“Chirico!”

Chirico leaned forward, and then–

“Hey!”

He looked to one side. A man stood there in plain sight.

Chapter 4

See the original post here

The man slowly approached and stood in front of them. The smell of the desolate land wafted from his face, his body, and what he was wearing.

“Were you trying to help us?” Chirico asked.

“Incorrect,” The man said in a thickly accented, generic Astrada dialect. He pointed at the gun in Chirico’s hand. “Such things should only be for humans.”

“Only for humans?”

For a moment, they didn’t understand what the man was saying.

Chirico said, “We are…”

The man interrupted Chirico and gestured for him to follow. “I have food.”

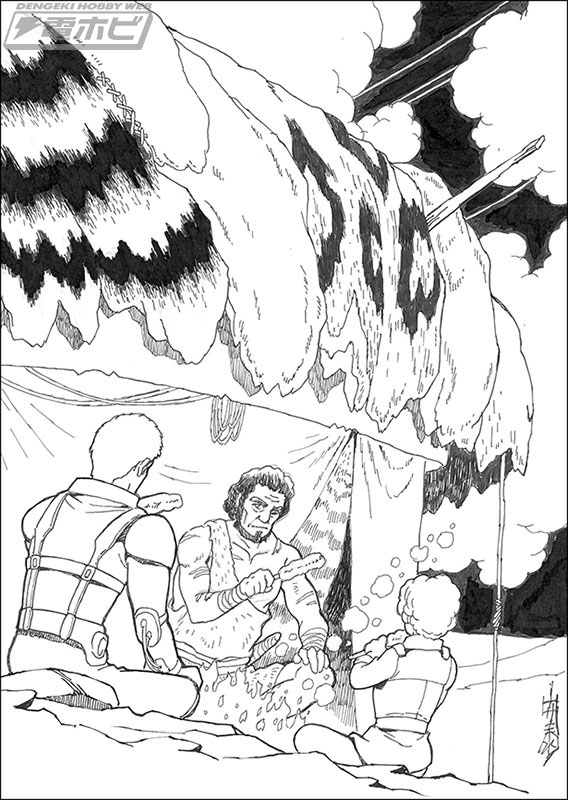

They walked for what seemed like ten kilometers until they finally arrived at the man’s dwelling, a lightweight, yet supple and strong lean-to made of tanned kabu fur.

“Paorun,” the man said proudly. It seemed to mean “tent” or “house.” Inside, there were things Chirico didn’t know how to use, but it was all for the purpose of survival on this land. There wasn’t a single industrial product, as if it was a rejection of civilization. The man built a fire and roasted something like sausage.

“Eat.”

He offered it to them. It tasted remarkably good, perhaps aided by hunger.

“Kabu?” Chirico asked, and the man nodded. “There are many of them here,” he chuckled. His laughter was light, a note of superiority without contempt for those who had wandered into this desolate land.

“What did you do to the urguns?”

At Chirico’s question, the man indicated a thrower woven from ivy and a pouch to be thrown. The man gestured for Chirico to smell the pouch.

“Ugh!”

Chirico abruptly turned his head away from the strong assault on his eyes and nose.

“They’re not going to be around for a while,” the man laughed. “The grantsua, too.”

“I see.”

Chirico made a decision.

“We want to stay here, too.”

Chirico and Lu moved their tent near the man’s paorun, within earshot if they shouted loudly enough. The great river was flowing close by, too. The man provided them with food for the time being. There were several natural refrigerators around, storage caches dug into the permafrost, preserving enough to meet their needs.

Within a few days, they learned a great deal from the man. Ranked in order of importance, the first would be the man’s name, “Seta Changil Gudurhon.” In the local language, it meant “cousin of the old ones.” It was too long, so they decided to call him Gudorn.

The next important thing was how to make insect repellent. He warned them, ” If you don’t wear this, your body will never be found.” It wasn’t difficult to make, and if they had the right ingredients, it wouldn’t take much time. All they had to do was mix three kinds of medicinal herbs into a juice squeezed from tallow.

The day came suddenly. Numerous black spots filled the air as if they were rising from the surface of the permafrost, loosened by sunlight. When Chirico brushed them off with his palm, they felt as if they were falling apart.

They reacted in surprise: Mossu! A super-sized mossu swarm! But they’re more like small flies! Whoa!

The insects bit any patch of exposed skin: face, hands, and feet. It didn’t matter if they were hit or shaken off.

“Get wet, quickly.”

Gudorn applied the insect repellent he was in the process of making.

(It doesn’t smell so good, does it?)

Despite this, Chirico desperately smeared the insect repellent all over his skin. The effect was immediate; the black cloud moved at least a meter away from his body.

“Oh, wow!”

“They’ll be gone soon.”

Gudorn was right. Within a week, the area was so thick with Mossu that it seemed as if the composition of the air had changed. Then, one day, they just disappeared.

“Where did they go?”

Gudorn blinked and muttered, “they go after a week. See you next year…”

Chirico muttered in reply, “So…they’ll be back.”

The three of them dropped the repellant into the big river to ward off more mossu. Even though it was summer, the water was cold and sharp.

“The life of a mossu is short. Maybe it’s because they’re small.”

“Maybe,” Chirico answered.

Lu threw a stone from the riverbank onto the surface of the river. “Small is boring.”

“Some things have been alive for 300 years,” Gudorn said.

Lu’s eyes bugged out. “Three hundred years!”

Lu had already learned the approximate lifespan of different creatures: human, kabu, urgun, and grantsua. Three hundred years was longer than any of them.

“What kind of thing lives that long?”

“A kind of fish. It’s very big.”

“Bigger than a grantsua?”

“Bigger than a grantsua.”

Two weeks went by after the mossu left, and the height of summer has passed.

“Kabu are coming.”

Gudorn began to prepare for the hunt. It was time to stock up on food for the year.

“Follow me,” Gudorn urged, carrying a few days’ worth of food. They set up camp in a hilly area a few dozen kilometers from the settlement. It was a good vantage point.

This time of year, he did not pitch a tent, but simply spread his portable furs on the ground. The howling of the urgun drifted into the night before the sun went down.

The next morning, as the three walked in search of kabu, they saw the vanguard of a herd at the foot of a hill.

“Those are the first ones. There are many more down there.”

“Are you going to catch one?”

“No…”

Just as Gudorn was about to answer Lu’s question, he stopped and said, “Look!”

He pointed toward a pack of urgun that had just appeared. In a spectacular display of coordination, they pulled one of the kabu free of the herd and began to drive it away. The single kabu, separated from the herd, tried desperately to escape, but it was soon cornered. Tired and unable to resist, it fell into the claws of the pack.

Gudorn heard the urguns’ howl of triumph and turned on his heels.

“Go back.”

“Aren’t you going to catch a Kabu?” Lu asked.

“I will, but it’s not safe right now.”

Gudorn urged them back to the camp.

“That’s the urgun’s way, and I have my own way.”

“Your way? Like what?”

“I’ll tell you,” was Gudorn’s only answer to Lu’s question.

Through the hunting style of the urguns, Chirico sensed that Gudorn was trying to show them more of his way of life in this land.

Chapter 5

See the original post here

The day to hunt the kabu arrived.

Gudorn’s preparations were quite simple. It was barely as tall as a human in the surrounding bushes. Branches from a type of willow tree were beaten to extract the fibers, which were then woven into a rope. The rope was fixed to a stake, and a ring-shaped trap was placed at the end. All that was left was to wait for a kabu to come.

“Hmmm.”

Chirico straightened the excess rope and said, “Lu, try pulling on this as hard as you can.”

He handed Lu a piece of the rope. Lu twisted the rope in his hands and pulled with all his might. The rope went taut between them, but he didn’t say a word.

“It’s so strong,” Gudorn said, “if you get your leg stuck in it, you’ll never get out.”

The traps were set in a hollow in the gently rolling hills that had been carved out by something. The three men set up camp nearby and waited for the kabu. A thin, parched herd of a few dozen to a hundred animals passed by peacefully. None were caught in the trap.

“They’re hard to catch,” Chirico said on the third day.

“There aren’t enough of them.”

Gudorn explained that the kabu herds were small, gathering gradually to number in the hundreds of thousands. A small incident within the herd could cause a stampede. The individuals then became less vigilant about their footing, making it easier for them to be trapped.

“What are the little things?”

“It’s a swarm of kabu-bai.”

“Kabu-bai?”

“They love nothing more than kabu.”

According to Gudorn, it was a fly that laid its eggs in the kabu’s ears and nostrils. There the eggs developed into larvae, feeding on blood to grow. Sometimes they ate through the mucous membranes and penetrate into the body, threatening a kabu’s life.

When a kabu-bai approached, a kabu would shake its head and legs to keep them away, which sometimes irritated other kabus, triggering them run. Lu listened to this story while holding his nose.

Soon, tens of thousands of kabu filled the undulating hillsides, just as Gudorn described. Then it happened suddenly. A great stampede. The ground echoed and roared, as if the earth itself was rupturing.

“Don’t worry, they won’t hurt us,” Gudorn said to Lu, who was cowering in the middle of it all. If the herbivorous beasts hurt their legs, it would be fatal. Collisions with obstacles were instinctively avoided.

The stampede was over in a dozen minutes. And as Gudorn said, two kubos were caught in two traps. One was struggling with a broken leg while the other was flailing about, trying to tear the trap to shreds. Gudorn’s spear accurately pierced their vital points and stopped them from moving.

From there, it was labor. They carried the carcasses to a nearby ledge, hung them upside down, and inserted a knife into their necks to drain their blood. Next, the skin was peeled off, the organs removed, and the limbs dismembered. One of the kabu weighed about 150 kilograms, and the other about 200.

The meat was divided into smaller chunks, placed in rough baskets, and exposed to the river water. When they had completed the entire process under Gudorn’s guidance, they showed no signs of fatigue.

Lu’s eyes lit up and he said, “Let’s do it again!”

“Did you like it?”

“It was fun. Let’s catch some more.”

Gudorn shook his head.

“We have enough.”

“We can give some to the urguns.”

Gudorn shook his head again.

“Or the gratsua.”

Gudorn shook his head some more. “We take only what’s ours. That’s the way we do it here.”

Lu’s eyes widened in thought.

“I see…”

His eyes followed the movement of the kabu in the distance.

The next morning Chirico was awakened by the roar of the earth.

(Kabu…)

When he looked to his side, Lu was gone. He sat up and saw Gudorn’s back.

“It’s early.”

Chirico moved closer to him and pointed silently.

“Hmm?”

There was a herd of kabu running by at full gallop. When the sprint ended, Chirico caught a glimpse of Lu in the direction of the sparse group.

“Lu?”

He ran over to find Lu spearing a trapped kabu.

“Lu!”

His happy face was drenched in sweat and blood, and Chirico’s voice seemed to fall on deaf ears. Lu stopped and ran to a struggling kabu a little further away.

“Stop!”

Lu used his spear again, seemingly oblivious to Chirico’s voice. The huge beast’s limbs trembled in a desperate spasm. Lu’s body, clinging to the end of the spear, shook like a rag.

“I got it! I got it!”

Before long, Lu pulled his spear from the kabu’s vital spot and looked proudly at Chirico.

“Five! I got five!”

Chirico wordlessly snatched the spear from Lu’s hands. It was slick with blood and Chirico’s hands were quickly smeared with the slime.

“I told you that was enough.”

“But it’s fun! There’s so many of them.”

Lu’s eyes were still following the herd, his instincts flaring with feverish intensity.

In the evening when they returned home, the three of them sat around the bonfire and roasted the kabu meat. Lu was still eager to hunt as he watched the fat dripping off the meat. His hunting instincts had awakened.

“There’s still a lot of kabu,” he said. “I want to catch more.”

“Gudorn said it’s enough, so we’re done.”

“But it’s fun.”

“We’re done.”

“There’s so many of them.”

“That’s good.”

“But it’s fun.”

“No, it isn’t.”

“Not for you, but it is for me.”

“It isn’t fun.”

“Yes, it is! Admit it!”

Their conversation was endless. Chirico’s logic could not suppress Lu’s instincts. In between, they ate meat and then went back to talking. Gudorn, who had been listening to their conversation, eventually blurted out, “What about the pigaigul?”

“Pigaigul? What’s that?

“The wolf of the river.”

“That thing you were talking about before, the one that’s been alive for 300 years?”

“That’s right.”

According to Gudorn, there were various theories. It was the king of this great river and was said to be over five meters long. It was seldom seen, but some claimed it swallowed kabu that came to the riverside for a drink.

“Can you eat it?”

“I don’t know. I never tried.”

“Can we catch it?”

Lu’s words were getting crazy as he was being dragged along by Gudorn. It was funny to Chirico.

“I don’t know…” Gudorn said, “I can’t do it alone…”

Gudorn said it took great strength to stand up to the pigaigul. They needed allies.

“What about the three of us?”

Chirico sensed that Gudorn was trying to tell something to Lu, who was obsessed with catching kabu.

“By the way, Gudorn, how old are you?”

“I can only count up to six, so I don’t know.”

Chirico told Lu that he was seven years old and left out any further explanation. And that was the end of the age discussion.

“Pokkan is a good way.”

“Pokkan?”

“Pokkan” was a fishing method. You put a hook inside bait and threw it into the water. The feeling of the hook was called “pokkan.” According to Gudorn, they would take a canoe out onto the river, put a hook in a lump of kabu meat, and “pokkan” it into the river. If the kabu was taken, it would become a contest of strength between the three of them and the pigaigul.

The challenge required the ultimate in physical strength. If they were not careful, the canoe would be overturned and they would be swallowed by the cold water, losing their lives in a matter of minutes.

“If we catch it, will it be food?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never had to do that.”

“Do you want to?”

“Hmm…I don’t know…it seems a bit crazy to me…”

“Does that matter?”

“Well…I can’t say it’s a good idea. Maybe we shouldn’t mess around with a god.”

“God? What’s a god?”

Chirico thought it was funny when Lu asked that.

“Something everyone should avoid fooling with.”

“Everyone?”

“Everyone in this world, including you and Chirico.”

“God is great.”

“Yes, great.”

Chirico listened to the conversation between Gudorn and Lu.

“It is humans who have always defied what God says…” he muttered to himself.

To Be Continued