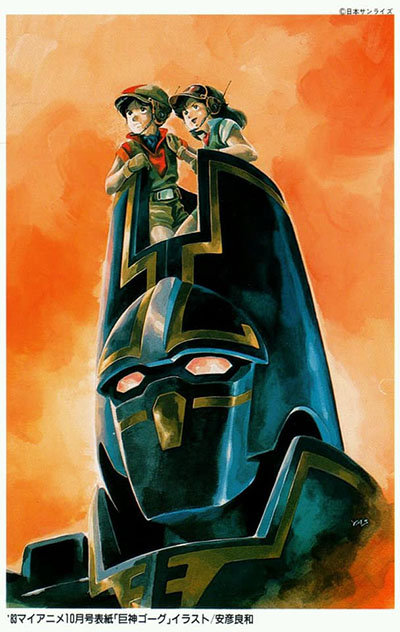

Series profile: Giant Gorg, 1984

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko is who I want to be when I grow up.

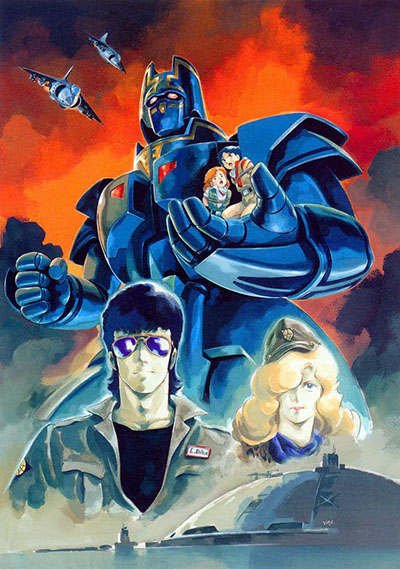

As with many of the best anime artists from Japan, I experienced his work before I knew who he was. The proper sequence of events for Japanese and non-Japanese viewers alike was to first be struck by the art and then seek out the artist. For me, his work most stood out in Crusher Joe (1983). Since he directed the film, it naturally carried all the hallmarks of his personal style. I’d heard of Mobile Suit Gundam, but didn’t actually tune in until Zeta Gundam (1985) where I recognized his character design style right away. And then came Giant Gorg.

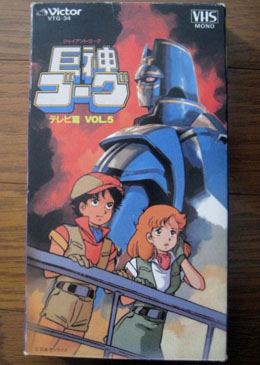

Before I proceed, I need to set the stage a little. Back then, there was only one way to get anime in its pure, undiluted form: on VHS. The format had been around since the late 70s, but didn’t become ubiquitous until the average household could afford a VCR in the early 80s. Once you had one, the next step was to find other anime fans who had started a collection through whatever means existed. Some had friends who recorded TV shows for them, such as military families stationed in Japan. One by one, those tapes found their way over the Pacific and the bridge-building began.

An underground tape-trading network was already growing by the time I got my first VCR in December 1984, and I plugged in right away. Putting together a complete TV series was a lot harder than it sounds. It could take months or years to find all the episodes, let alone find them in good condition. But once in a while you’d get extraordinarily lucky and score all of them in one trade. The very first series that ever came to me that way was Giant Gorg. It became the first pure, untranslated anime series I got to binge watch, and it was pure heaven all the way through.

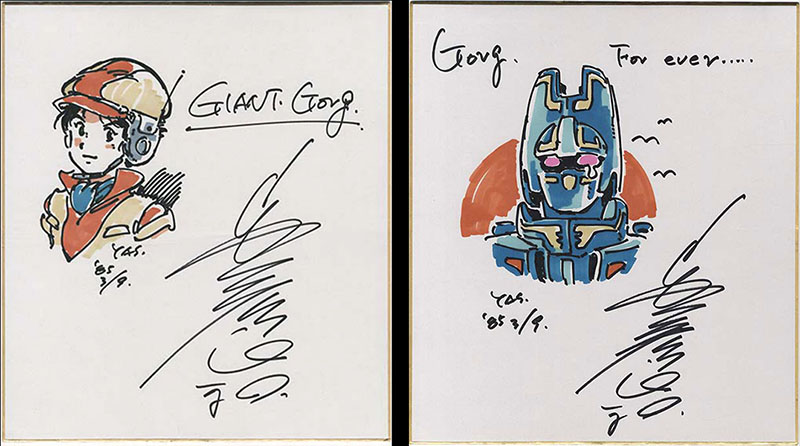

Before that mighty score, I’d seen random episodes on a sampler tape and instantly recognized the signature Yasuhiko style: warm, organic characters that flowed like brushstrokes and smooth, inviting linework laid down with practiced confidence. Watching it literally come to life on a screen was breathtaking. On my best days, I sort of draw a little like him. On all the other days, I just do my best to catch up.

To explain what made Gorg so special to me, I need to explain something about animation production: it takes an army. The leader of that army is the Director. One step down from that position is the design team. Design is typically divided up into characters, mecha/props, and backgrounds, handled by specialists in each category. They create the reference materials animators use to draw the scenes you actually watch on your screen. If the animators are good enough to draw exactly on-model, you won’t notice any variation in how those things look, especially the characters.

The reality of the situation, especially in anime of the late 70s and early 80s, is that variation was inescapable. The industry was in a rapid period of growth, and quality was all over the place. It was quite common for characters to vary wildly from their original designs depending on which studio handled which episode and how fast they had to complete their work.

To digress a bit from that digression, you see far less variation these days because character design skills have largely homegenized. The output from Japan is now so enormous that it actually works against you to have unique character designs. Animators can more easily maintain high output if they don’t have to relearn new ways to draw characters. Thus, you have a better chance of keeping your show on schedule if it looks pretty much like all the other shows. There are exceptions, of course, but they are inevitably more expensive to make.

As anime went through its early 80s renaissance, character designers pushed the limits of their craft. Their work was distinctive and every show had its own flavor. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko had been designing anime characters (and drawing manga) since the 70s, and when he made his mark with Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) he found himself elevated to a director’s seat in short order. He was one of the few directors who could literally do the job of an ENTIRE design team. And he ultimately did exactly that on Giant Gorg.

One of the few other auteurs with that formidable skill set was Hayao Miyazaki. Prior to founding Studio Ghibli, he helmed a TV series called Future Boy Conan (1978) where he accomplished the impossible; wrote, directed, designed, and ANIMATED all 26 episodes. By that I mean he single-handedly created the animation layouts for the whole thing, a job so huge it normally requires a squadron of animators. Yasuhiko, like everyone else in the industry, was blown away by the results. But unlike everyone else, it gave him a hunger to do it himself.

Layouts come between storyboards and key animation. If you’ve looked at the storyboards I’ve posted elsewhere here on ArtValt, you’ve seen that they have to be fairly detailed. This is because they have to communicate the intent to animators in another country, usually Korea, who may not speak English. In Japan, storyboards can be far rougher, more like a thumbnail, because they stay “in house.” Layouts have about the same level of detail as American storyboards, but they’re drawn at the same size as a cel. From there, key animators refine the drawings and inbetweeners add poses.

Key animators on a typical anime show would start by doing layouts and then refine them. On Future Boy Conan, Miyazaki took that weight off their shoulders and did them on his own for the entire series. This is a superhuman amount of work that takes a superhuman artist to pull off. By all measures, Miyazaki is superhuman. In the early 80s, Yasuhiko earned his own super-stripes on the three Mobile Suit Gundam movies and Crusher Joe, but those were feature films. Giant Gorg was going to be his Future Boy Conan.

Watching Giant Gorg, then, is as close as we could get to seeing an entire series drawn by Yasuhiko. His soul is in every frame, and the last episode looks as good as the first. The best part of the story is that you don’t have to hunt it down on VHS. It’s available to binge watch RIGHT NOW on DVD from Discotek, streaming on Amazon Prime, and free on Crunchyroll, Youtube, TubiTV, and Retrocrush.

I haven’t said much about the content of the show because it’s described in the interview below. Suffice to say it’s loaded with action, mystery, suspense, and moments of pure joy, driven by a passion for the moving image that always inspires me to up my game. Click on the links and see with your own eyes what a superhuman can do.

Originally broadcast April 5 to Sept 27, 1984

Produced by Sunrise

Sponsored by Takara

Chief Director/Character Designer:

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko

Screenplay:

Masaki Tsuji (14 episodes)

Yumiko Tsukamoto (12 episodes)

Music by Mitsuo Hagita

Individual episodes on Youtube:

Creator Interview

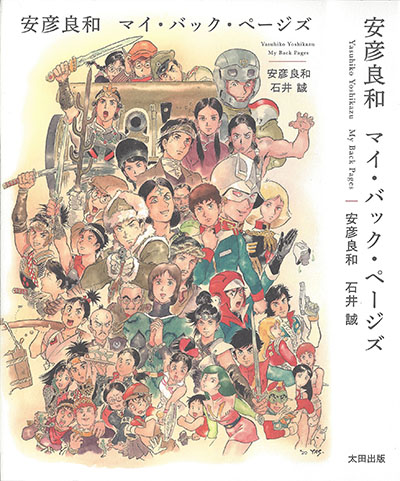

Translated from Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, My Back Pages

Ohta Books, November 2020

Culled from over thirty hours of interviews conducted by Makoto Ishii for Continue magazine, this book covers Yasuhiko’s entire career. Presented here is the chapter devoted to Giant Gorg.

Giant Gorg was supposed to be a free work

“It’s going to get darker.”

That’s what Yasuhiko told me first when I asked him to talk about his three works, Giant Gorg, Arion, and Venus Wars.

His first film, Crusher Joe, was well received by anime fans, which further increased their attention toward him. Nippon Sunrise also began to think about a new film with Yasuhiko as the creator.

The first project Sunrise started was the TV series Giant Gorg in the fall of 1982, just as the production of Crusher Joe was coming to an end. The film was a theatrical adaptation of a novel by Haruka Takachiho. Yasuhiko himself wanted to break away and make an original work, and Sunrise wanted to release a Yasuhiko original to the world.

Toy maker Takara (now Takara-Tomy) signed on as a sponsor, and the project began to move forward. At the time, the idea was to make a presentation to the sponsor while planning the anime. They had to find a way to get people interested in the work, and plan how to commercialize it. It is common for a work plan to evolve in parallel with commercialization. As a result, merchandising is released at the same time as the broadcast (toys and model kits in the case of robot anime).

If a design did not meet the sponsor’s expectations, or if it was not likely to be commercialized, the project itself was often rejected. Unless an artist is very well known or has a popular original manga, it is difficult to produce a creator-led TV series. However, the door was open for Giant Gorg on the premise of respecting Yasuhiko’s authorship, and having a sponsor attached would make it possible to create a work that was very unusual at the time.

The only thing the sponsor wanted was a robot that could be commercialized. The story, the concept, the design, etc. would be produced without any interference.

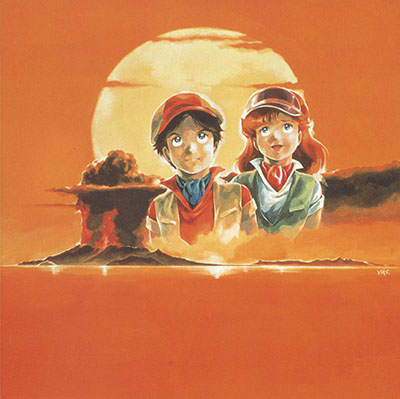

Giant Gorg is set in the year 1998. In 1990, a tectonic shift occured in the South Pacific Ocean, causing an underwater volcano to erupt. As a result, a new island was created. Named “Austral New Island,” it was reported in the popular press as having sunk under the sea again, and it was erased from the map.

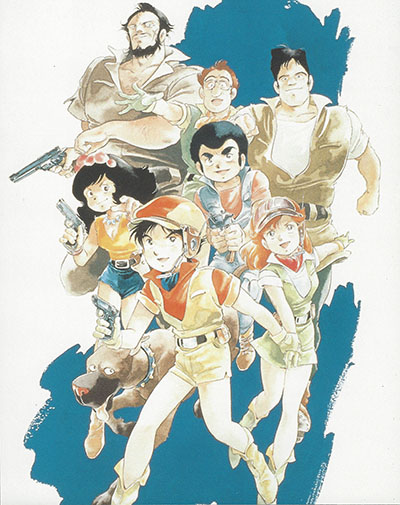

Yuu Tagami, a 13-year-old boy, is the orphaned son of Dr. Tagami, a leading researcher of Austral New Island. A letter left by Yuu’s father urges him to visit his colleague Dr. Wave in New York and learn more about the island. However, Wave is being targeted by GAIL, a huge military-industrial complex. Evading GAIL’s hired guns, Yuu escapes with Wave and his sister, Doris. They meet up with Wave’s friend, a skilled mercenary called the “Skipper.”

They decide to go to Austral New Island, which Wave believes still exists despite news reports to the contrary. What’s more, It contains ruins of mysterious origin. GAIL understands the value of the island and has sealed it off to conduct private research.

GAIL branch manager Rod Balboa arrives on the island to conduct “aggressive research” using his private army. Yuu and his team are on their way when a mysterious monster attacks and sinks their ship. Everyone is rescued by guerillas who were driven to a remote edge of the island by GAIL.

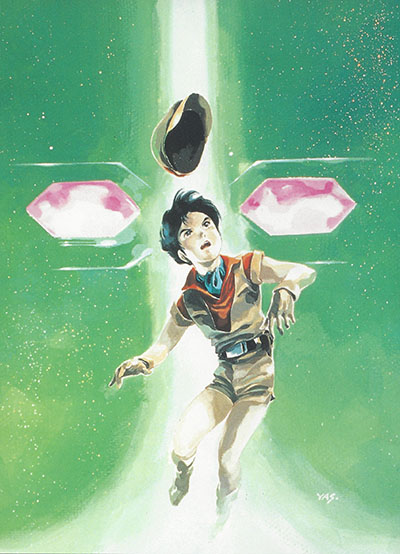

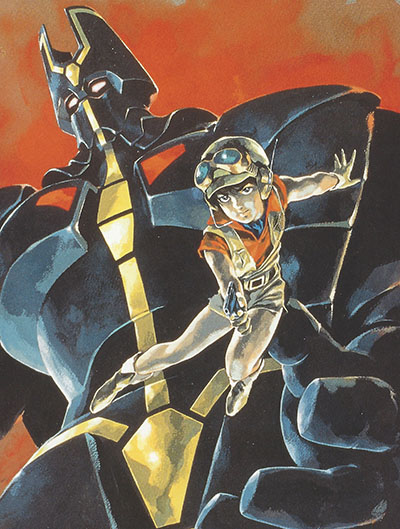

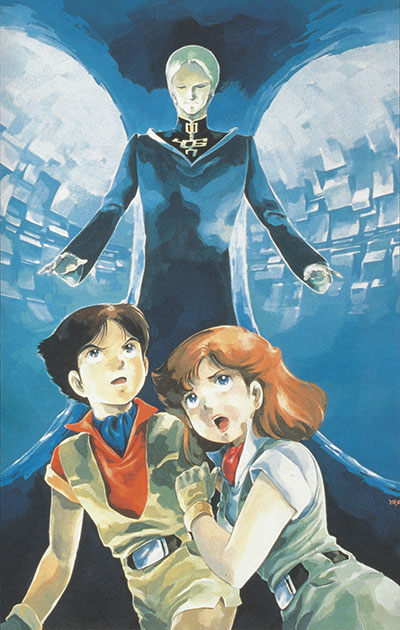

Separated from the others, Yuu washes up alone on the shore and is attacked again by the monster, but he is saved by a blue-colored giant named Gorg. Gorg is a giant, self-sustaining robot that was created to protect the island’s secret. After communicating with Gorg, Yuu joins up with Doris and the others. Some of the guerillas join them with Gorg as the key to the island’s secrets.

A battle over those secrets is about to unfold.

The title character is a giant robot and the adventure takes place on an uncharted island full of mysteries, a conspiracy involving a huge corporation, and the legacy of an ancient alien race.

The production system for the series continued from Crusher Joe, and Yasuhiko single-handedly drew the layouts for all 26 episodes.

On Crusher Joe, I did over 2,000 shots. I asked for a little more time in exchange for less manpower, but we did it. Layouts for all the shots. So I decided to apply that to TV.

However, Giant Gorg did not receive much recognition in the animation industry at that time. This was the element that led to Yasuhiko’s words at the beginning of this article. “It’s going to get darker.”

I’ve always thought that it was possible to make anime in the adventure genre for my generation. I thought a treasure hunt like in Treasure Island would be a dream come true, but I didn’t think anyone would be interested in the jungle or desert expeditions of the past.

At that time, even though we didn’t have GPS or any other tracking system, it wasn’t realistic to go on an adventure in an unknown world where no one had ever been before. That’s why I thought a lot about how to make a treasure hunt possible in the modern age when I was planning the project.

I thought that even if it didn’t make a big splash, it might still make some waves, so I gave it a try. But in the end, there was no response at all. It wasn’t so much that I was disappointed, but rather that I had bad luck. It coincided with a time when the tide was changing.

What does Yasuhiko mean by “the tide changing?” When Giant Gorg was broadcast in 1984, the year was also marked by the groundbreaking anime feature films Macross Do You Remember Love, Urusei Yatsura 2 Beautiful Dreamer, and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.

Macross was an adaptation of a TV series, but it was treated as a completely new work, which increased its degree of perfection. Beautiful Dreamer had very high quality storytelling by pushing Director Mamoru Oshii’s creativity to the fullest, without being bound by the original manga. Nausicaa was Hayao Miyazaki’s first film as a director in a long time and became a catalyst for Studio Ghibli.

Each of these films took a new approach that was different from previous animation works. It can be said that they each changed the viewpoint of fans who watch anime. Giant Gorg was left behind in this huge wave of change. Yasuhiko, who witnessed this situation, recalls…

Giant Gorg was originally scheduled to start broadcasting in October 1983, but it had to be delayed by six months. At that time, the tide turned completely. The dual release of Macross by Haruhiko Mikimoto and his team, and Nausicaa by Miyazaki was a real boom. Those who wanted to watch high quality anime went to Nausicaa while those who wanted to watch otaku anime went to Macross. I was completely left behind. The fans who were there were visibly disappearing. It was a very symbolic thing that happened.

The original plan to air the show in the fall of 1983 would have been very good timing. It gets colder in the fall, so more people watch TV at home. On the other hand, in spring the weather is nice and they don’t watch TV while the sun is out. That’s why the start of the spring broadcast was the worst timing for Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) as well.

Gorg was delayed because Takara could not release the products they were developing in time for the broadcast, so they asked me to postpone the project for six months. I couldn’t take a break from production just because the broadcast started later. If we took more time, they would complain that the cost had gone up again, so we kept producing at the same pace.

The production period ended up taking until May, finishing a month after the broadcast started. Another thing I can’t forget is that we released the [VHS] video before the start of the broadcast. As a result of the extended production period, the costs were higher. They wanted to recoup the production costs, so they decided to sell the video first in an unusual way.

That was an act of betrayal to the people who looked forward to watching the show. When they sat in front of the TV every week and watched it, I wanted each episode to say “to be continued,” but the video was already available. I got the feeling that releasing the video was mandatory for the production, so I couldn’t protest.

Another symbolic situation was a screening event we held in March (a month before broadcast). We screened the fourth episode in a theater, which ended with the appearance of Gorg. The venue was packed with people, and it was a huge success. The fans who saw it said, “It’s fun!” I felt very confident and thought I could do it.

Around July we decided to do screenings mainly in western Japan to sell the video, but by that time, not even half of the venues were filled after there were so many people in the spring. That’s when the tide changed dramatically. I haven’t had a good experience with Gorg since then.

This was his first completely original work, so he was very particular about the production system. However, problems arose in various parts of the planning process, which were initially left to chance.

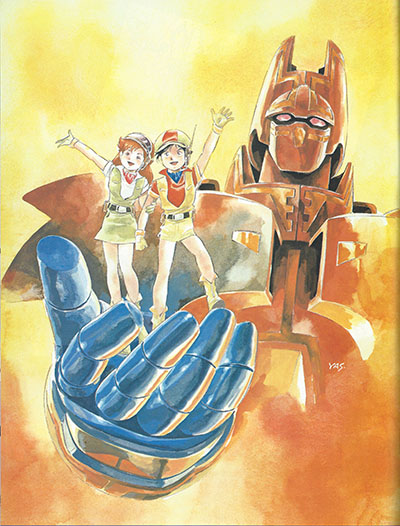

It was my dream to create a TV series where the art is consistent all the way through. Future Boy Conan was a work where the drawings were the same from beginning to end. I couldn’t beat it in terms of content, but I wanted to achieve that level of artistry. That’s why I didn’t go to voice recordings, and left everything to the sound director and voice director. I just kept on drawing, and that was part of the reason why I worked so hard on this.

At the time, I thought it had a nostalgic feeling and that it would still work. But it was not to be. Years later, I watched an international anime called Iron Giant. The robot is simple, but it transforms a little bit and produces something like a laser beam that causes massive destruction. It was cool. I thought to myself, “Oops, I should have done something like that” (laughs).

The fact that Gorg was a very simple robot was one of the key factors. It doesn’t have anything like flying fists or beams. All he can do is throw rocks. The sponsor seemed to be troubled by that kind of robot. As a result, commercialization was delayed. I guess I should have done something like Iron Giant.

In thinking about Gorg, the image I had in mind was Osamu Tezuka’s Majin Garon and the tokusatsu [live action special effects] movie Daimajin. Tetsujin 28 was a weapon, but when the enemy took his remote control, he became the enemy. Gorg is more emotionally driven and thinks in images.

Majin Garon fights with a small boy in his chest. When the boy is in his chest, he works harder. I wanted to make it heartfelt like that. Anyway, I wanted to do something nostalgic in every way. I had always promised that the story would have a robot, and by setting up a robot like Gorg, I felt that I had graduated away from robots that combined and transformed.

My mentor, Kiyomi Numamoto, who was working at Takara at the time and was the director of the Mushi Pro Training Institute, let me meet Takara’s president. At the time, it was Yasuta Sato, who had made Takara a success with a famous toy called Dakko-chan. He said, “I’ve made a lot of money from Dakko-chan, so I don’t need more money. You can do whatever you want. I don’t care if it sells or not.”

I thought, “How generous is that?” I was really touched and grateful. So I got carried away and submitted a robot that they couldn’t do anything with. It wasn’t a question of whether the design was good or bad, it was more a question of, “What can it do?” There’s a lot of talk about play value and so on.

They’d say, “Doesn’t it combine with other toys? Will there be a light coming out somewhere, or will the fists launch? If not, there’s no way to make toys.” I could have said, “You told me you made enough money with Dakko-chan and you don’t need this to sell,” but that seemed rude.

Takara and I fought a lot and the products were delayed. Mr. Numamoto was caught between the two of us. He said, “You can still do something with it. Have it throw rocks. If you have something, we can do something.” I was told there wouldn’t be a toy. But it came out anyway. They came up with a rock-throwing Gorg toy.

At the same time, the state of the anime industry was undergoing major changes. As stories and concepts became more and more profound, it became impossible to keep up. Yasuhiko believes the failure to keep up with these changes was the failure of Giant Gorg.

At that time, the mecha concepts were becoming very hardcore. Haruka Takachiho told me, “Yasuhiko-san, you need to get a mecha supervisor to do the mecha designs right.” I guess he was watching from the side and thought he should give that advice.

I had studied a little about modern weapons, but couldn’t keep up with the hardcore fans. Even if I wanted to use handguns in the show, I didn’t know anything about them. I didn’t even know that there were two types of handguns, automatics and revolvers. I had no idea, and I didn’t have anyone on the staff to advise me on weapons.

But around that time, Mamoru Nagano started coming and going at Sunrise. He was helping Yoshiyuki Tomino with some of his anime works, before he was as prominent as he is now. I heard, “There’s this weird guy Nagano, he’s a real mecha otaku.” So I called him up and said, “Come here and teach me.”

He explained how to fight tanks, and that there were two types of artillery, howitzers and cannons, and so on. I can draw a good amount of mecha myself. I did Crusher Joe without a mecha director. So I thought, “I don’t need a mecha director.” I thought I could still do it on my own at least. But it didn’t turn out that way.

While he was trying to do something “old-fashioned” with Gorg as the main mecha, and the adventure story presentation, the story takes on a science-fiction approach with the military-industrial complex trying to control the island, and a “second contact” story between humans and aliens in a long sleep.

What kind of thought was put into those concepts in 1984, when real robot anime was at its peak?

Recently, an underwater volcano erupted and created a new island called Nishinoshima. When I saw the news, I thought, “It’s just like Gorg.”

It was a perfect image. It’s not a completely uninhabited island, it’s a small island that’s barely on the map, but there were plants and animals living there. It is said that it will continue getting larger.

I made a detailed map of Austral island according to such concepts. If you got the treasure map of such an island, you’d think, “What the hell is this?” I wanted to create that kind of excitement. But at that time, looking at maps as a hobby was not very popular. Pirate stories like One Piece and Pirates of the Caribbean became popular later on, but it didn’t happen at that time.

That’s what I mean when I say that I didn’t have the ability. Even if you’re unlucky, you can make something succeed if you have overwhelming power of expression. I think elements that were not considered appealing at the time could have been turned around.

The concept of the relationship with aliens was also something I had originally thought about. I didn’t think a traditional pirate treasure would be possible. I thought about what the treasure could be, something that would make the world go crazy if it was discovered. If it had something to do with aliens, it would be something you couldn’t ignore.

However, I couldn’t get into first contact stuff like Close Encounters. There is no chance for a meeting between humans who have barely reached the space age and people who are more advanced. There would definitely be a time lag. In Gorg, there was a time lag of 30,000 years. So aliens have come, but we couldn’t contact them. They’ve been sleeping for 30,000 years until the time comes to contact the developing human race. The timer was activated, and the island came to life. However, actual contact would be very unfortunate.

I’ve worked with such concepts in previous stories using science-fiction settings. I think it was not such a bad idea.

On the other hand, the relationship between aliens and earthlings is a subject that has come up a few times in Yasuhiko’s later works. It is an element of “indigenous people leveling up when influenced by advanced civilizations.” It’s not just science-fiction, but ancient history as well.

I wrote about that concept in my later [manga] work, Star of the Kurds. Recently, it has been found that there was no major disconnect between the Neanderthals and the Cro-Magnons. Previously, this ancient tribal connection was a missing link in history. At that time, it didn’t sound so absurd that the ancestors of modern humans could have come from outer space and their descendants were connected to the present. In our story, we set that time lag at 30,000 years.

In addition to the SF concept, since the story took place in the present day (or near future) of the 80s, the Cold War was also an important part of the backdrop. Although the story is not very political, the excitement of the climax was, “a nuclear war could happen at any moment.”

I didn’t want to get into politics, but the Cold War was about to change with the emergence of Yuri Andropov as a leader in the Soviet Union. In such a situation of capitalism versus communism, what would be the great evil? If there is such a thing as a big conglomerate company that swallows up all the differences in those systems, wouldn’t that be the greatest evil? Not a secret society or a political organization, but a large corporation with its own private army. I thought this could have a lot of reality to it.

If you discover a treasure that surprises the world, larger forces will inevitably turn their attention to it, and to some extent a political situation will be created. And then there is the question of how to cover it up. That’s why I decided to end the story like I did.

Giant Gorg is a work of high quality, even from today’s point of view. It is still supported by many fans, and new related products have been released. However, it is still a big shock for Yasuhiko that he was not able to make it a success.

It was overwhelming when the tide turned. It was a real shock. I call it “Gorg shock,” but it also made me realize how scary this world is. It wasn’t about my own evaluation of the work. If others who see my work say, “It’s interesting,” that determines my own evaluation. “I did my best. It should be interesting. I think it’s pretty good.” But if the people around you don’t respond, you end up thinking, “I guess it’s not good enough.”

I don’t have the confidence to say, “I don’t care what anyone says about my work.” Or, “my work is great no matter what anyone says.” I know it’s not bad, but it’s not good enough. In terms of quality, Mobile Suit Gundam is terrible. I made a lot of compromises, and I can’t help it if people find it rough, but it still became a hit. So when people say, “You’re great,” I think, “Really? I’m not sure.”

If you have a hit, it’s interesting when they see the pockmarks as dimples. But if you don’t have a hit, the pockmarks are all just pockmarks. I think the fear of that is always there.