Mecha Mania, 2002 (Part 2)

In part 1, I described how I got the assignment to draw robot designs for the first segment of Chris Hart’s Mecha Mania book. As you may recall, I was not 100% thrilled with Chris’ presentation choices. Shown here is my work for two subsequent segments, which I also took issue with for…reasons.

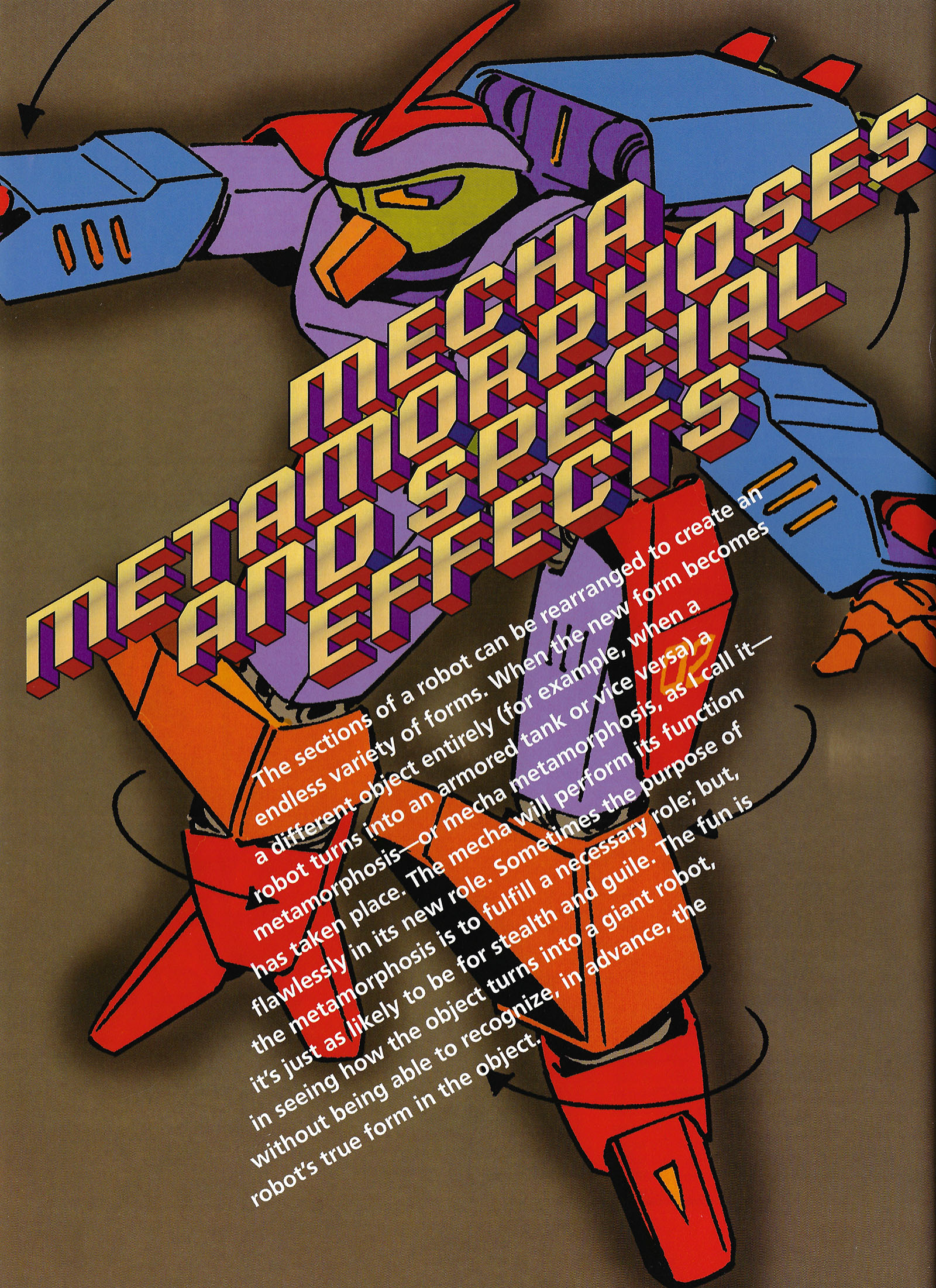

That’s the title page for one segment, but that’s not my art. Several artists contributed to this part of the book, and Chris put our work into different categories. I have to throw some skunk eye at the cheerleading in the opening text. Sure, it’s fine to applaud individuality, but…”You can’t make a mistake”? If that were true, then why does a book like this – or teaching art in general – exist at all?

You can for sure make a mistake. This drawing right here has some mistakes in it. There are errors in the symmetry. There are errors in the coloring (a sure sign that the artist and colorist were two different people). The trick is to learn how to recognize mistakes and correct them. My approach to this would be more like, “you’re going to make mistakes (because they’re inevitable), but you’re also going to learn things by making them.”

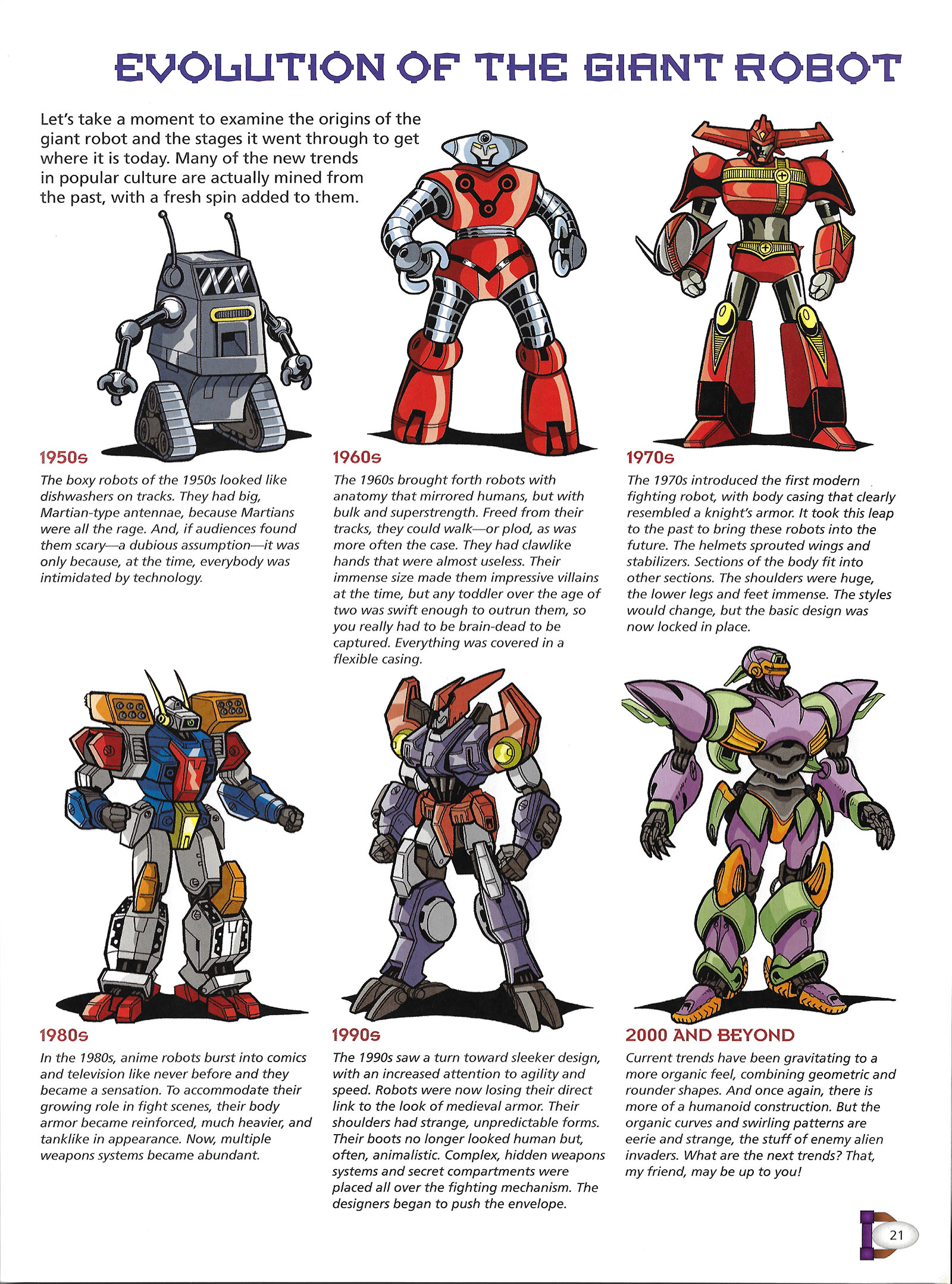

Oh boy, this page…

First off, I should state that none of those drawings are mine. And I’m pretty sure they were all done by the same artist. I wouldn’t have drawn them that way, but I have no particular beef with them.

But that text…

Just about everything in that text is wrong, or at least oversimplified to the point where it may as well have been made up by someone (Chris) who decided one hour of research was enough. First, this book was meant to cover anime robots, which didn’t exist in the 1950s. Second, the decades became increasingly hard to generalize as they went on, so if you only have one page to cover them all, you’d serve your readers better by citing the names of specific designers.

I would have cited Osamu Tezuka as the taste maker of the 60s, Go Nagai for the 70s, and Kunio Okawara for the 80s. After that, SO many individual designers broke ground that I can’t put any of them at the top of the heap. In Japan, whole books have been written on the topic Chris tried to sum up in one page. Japan even had the courtesy to break it down into two categories for us: Super robots and Real robots. It doesn’t need to be any more finely distinguished than that.

I could go on and on, but there are more pages to get to.

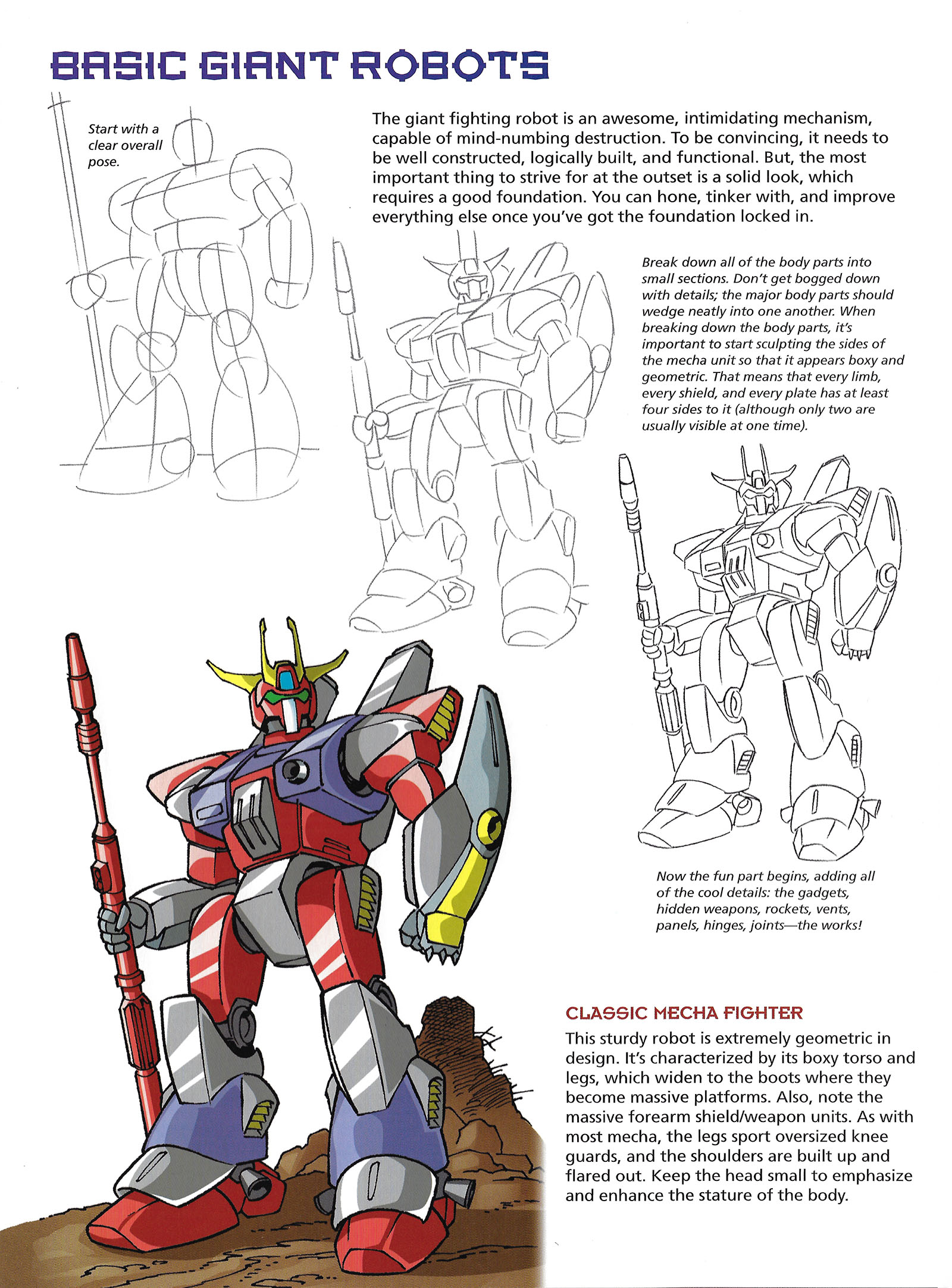

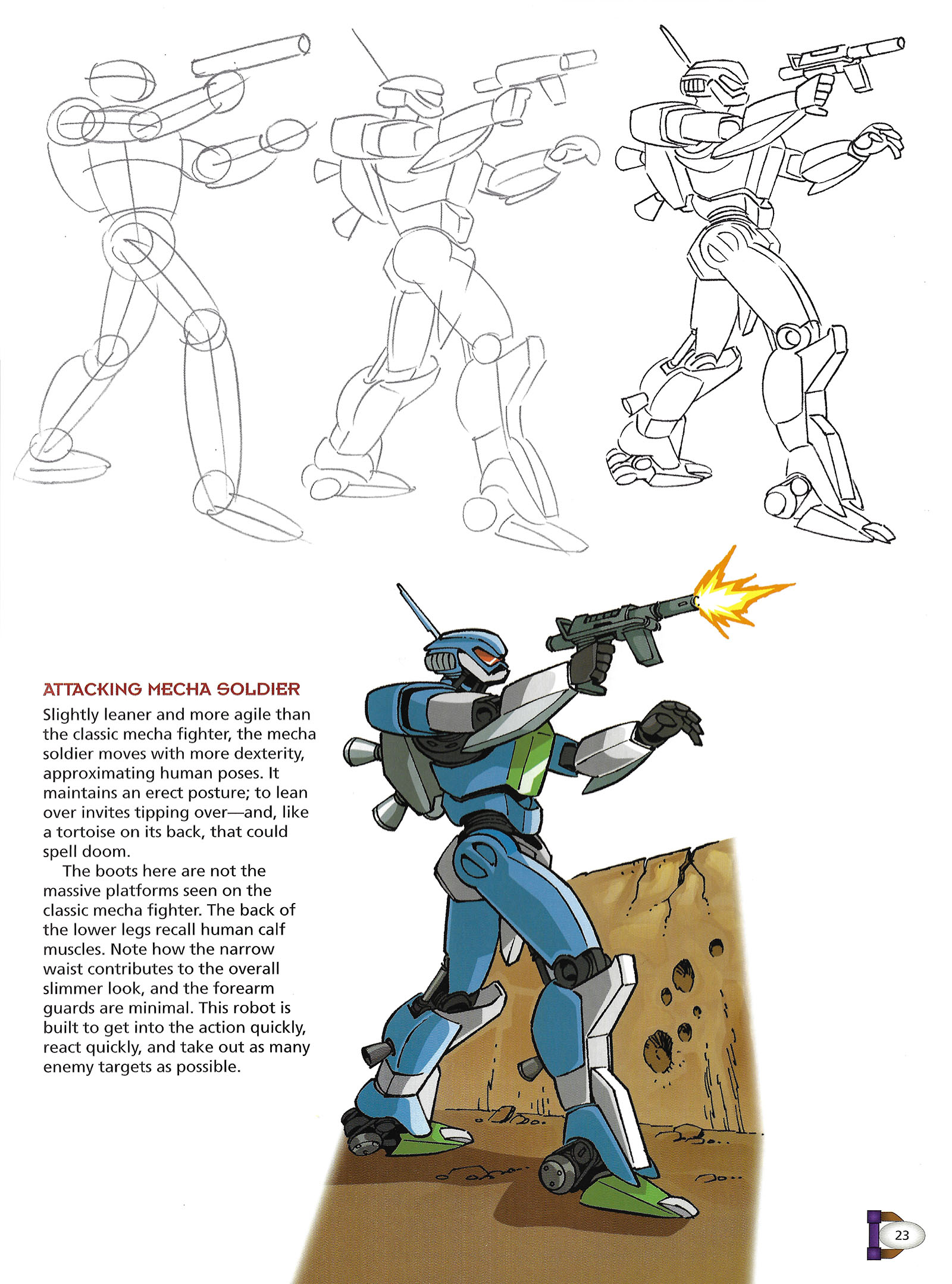

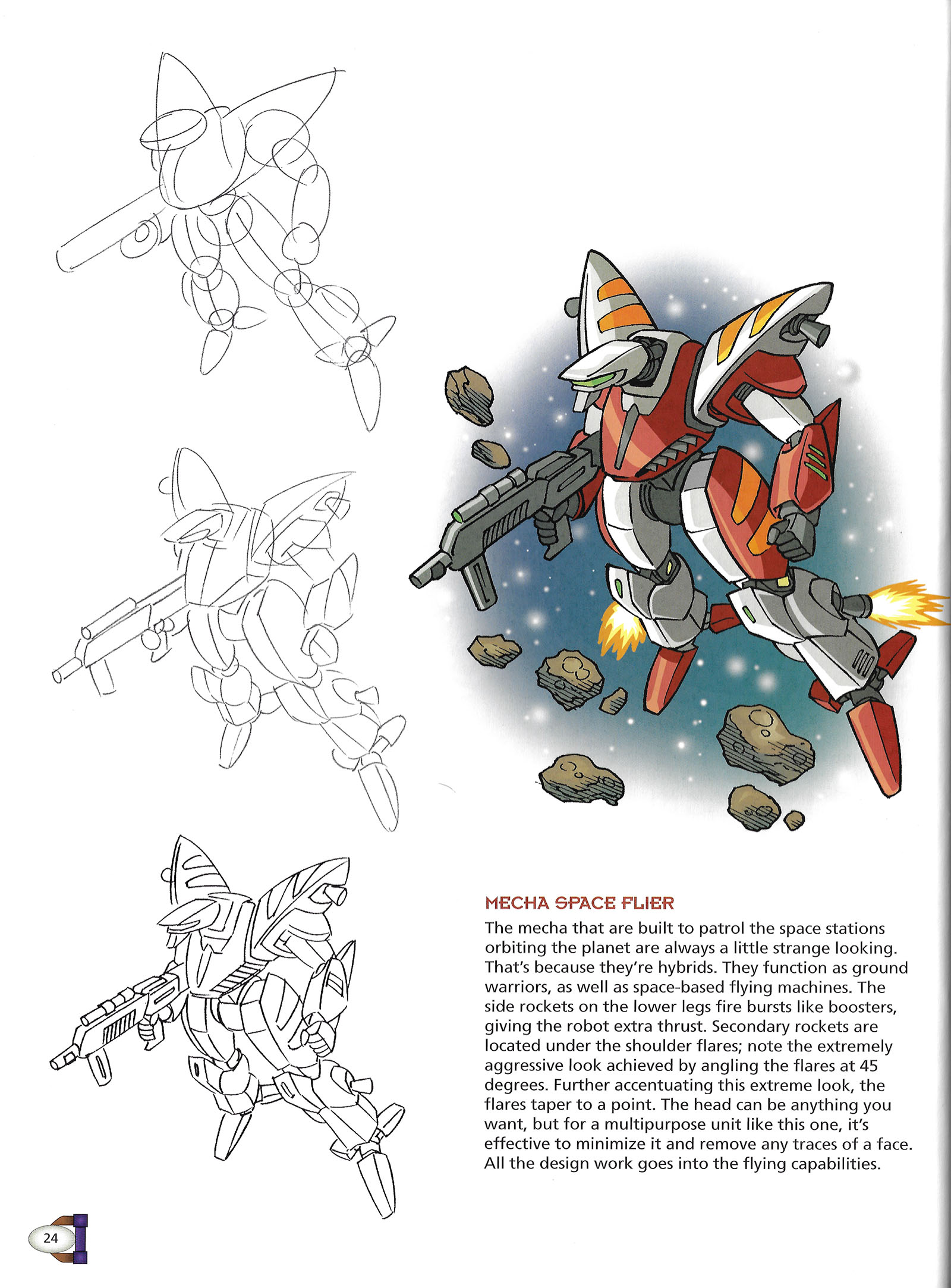

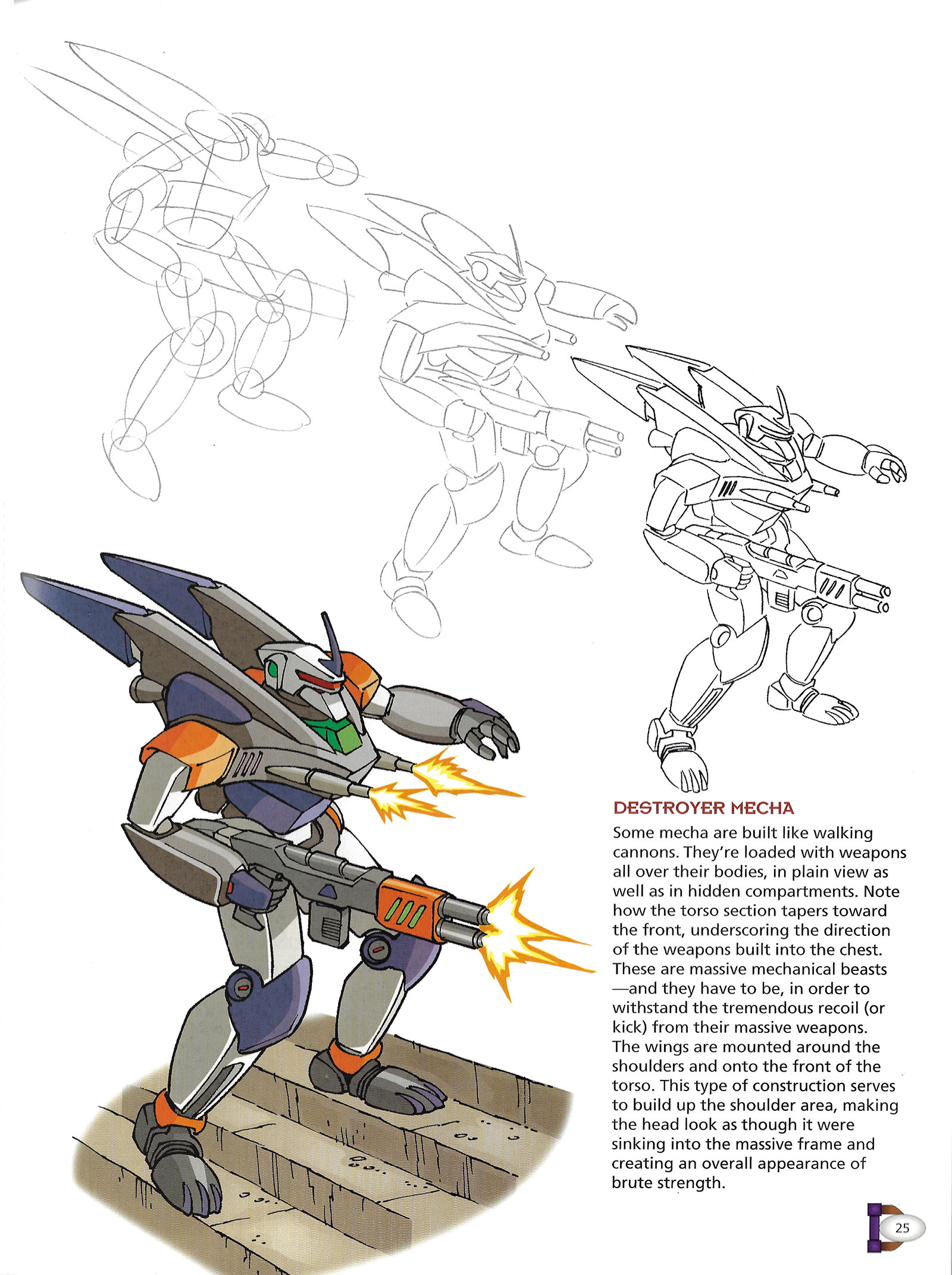

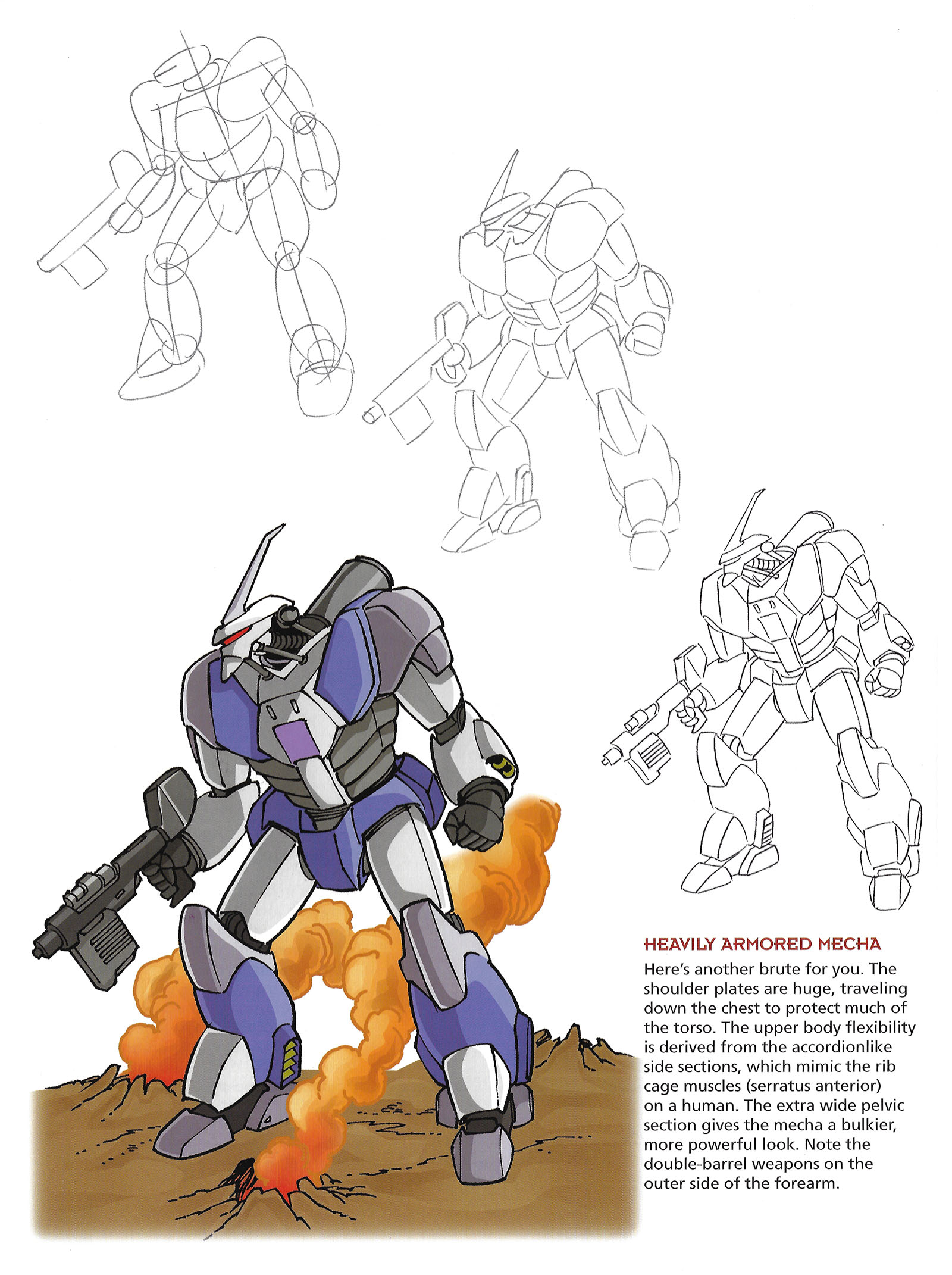

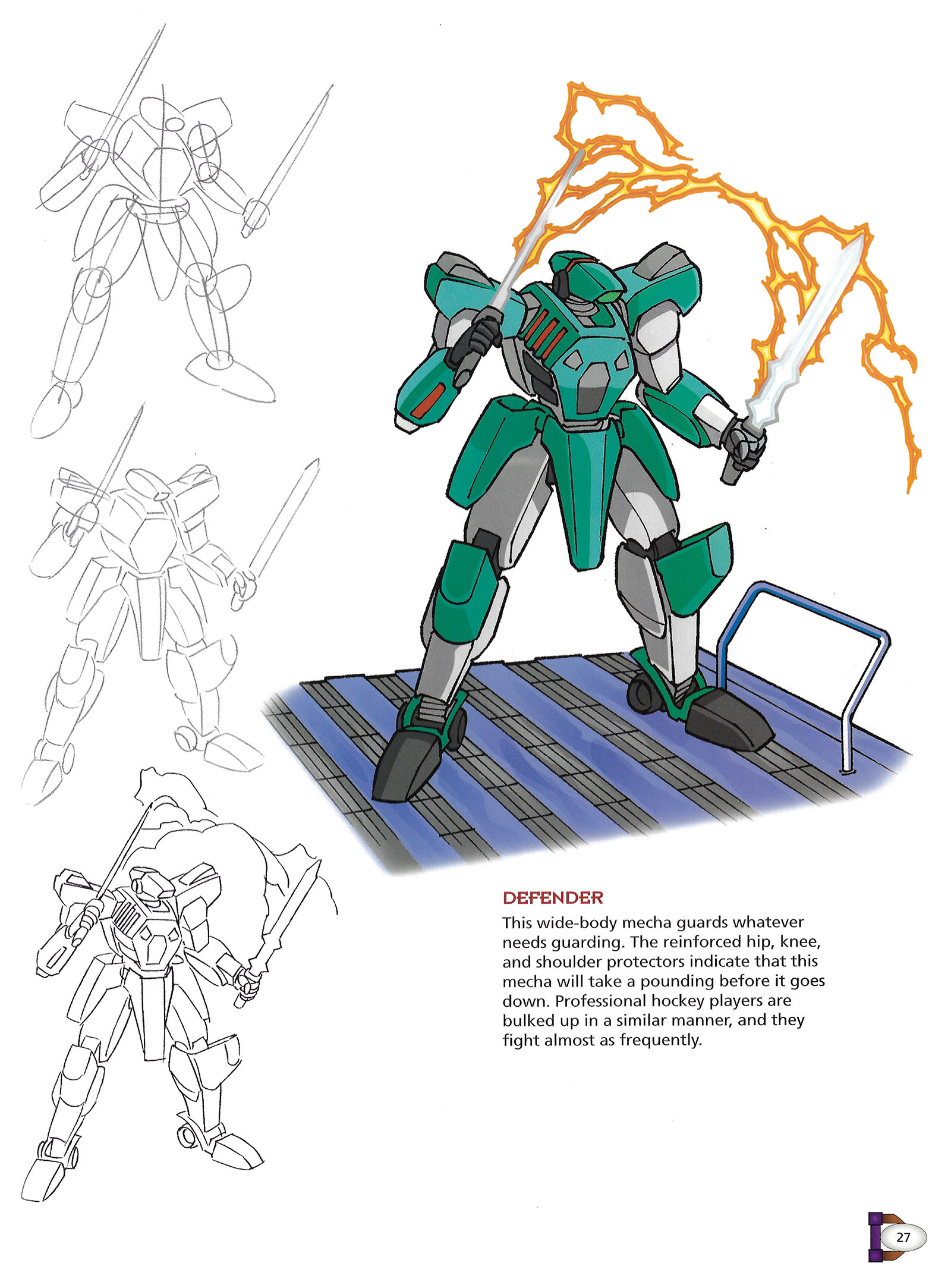

My portion of this section of the book was “Basic Giant Robots.” Chris asked me to come up with six different designs and show them in four stages. Since I groove on Kunio Okawara style mecha design, I started from there.

Chris wrote the text after I submitted my designs, and I would have rewritten about half of it if given the chance. And I definitely wouldn’t have put names on them. All of these names instantly shove your imagination into a box and limit your potential.

That note about a tortoise tipping over is complete nonsense. A humanoid body isn’t subject to that problem. And no comment on the built-in foot wheels or exposed joints? Really?

Almost none of what Chris wrote in this description went through my head as I came up with the design. And there’s nothing about weight distribution, center of gravity, or design stability. None of that complex stuff that comes from real life and makes a design more plausible. Just made-up gibberish.

Did you notice how the sweeping shapes on this robot make it look like it’s moving quickly, even when standing still? Or how the feet look like running shoes, as if built for speed? I don’t think Chris noticed that. At all.

Did you notice how a lot of my designs have vents on them, because moving parts in enclosed spaces (like car engines) tend to build up lots of heat? Or that you sometimes see exposed machine parts, say around the neck? Or that you sometimes need to think about where a power source should be mounted? I don’t think Chris noticed.

UGH. How about saying something about bulking up armor in places where it won’t interfere with movement? That might be helpful. Pro tip: if you’re going to hire an artist to design robots for you, ask them about their thought process instead of just making things up.

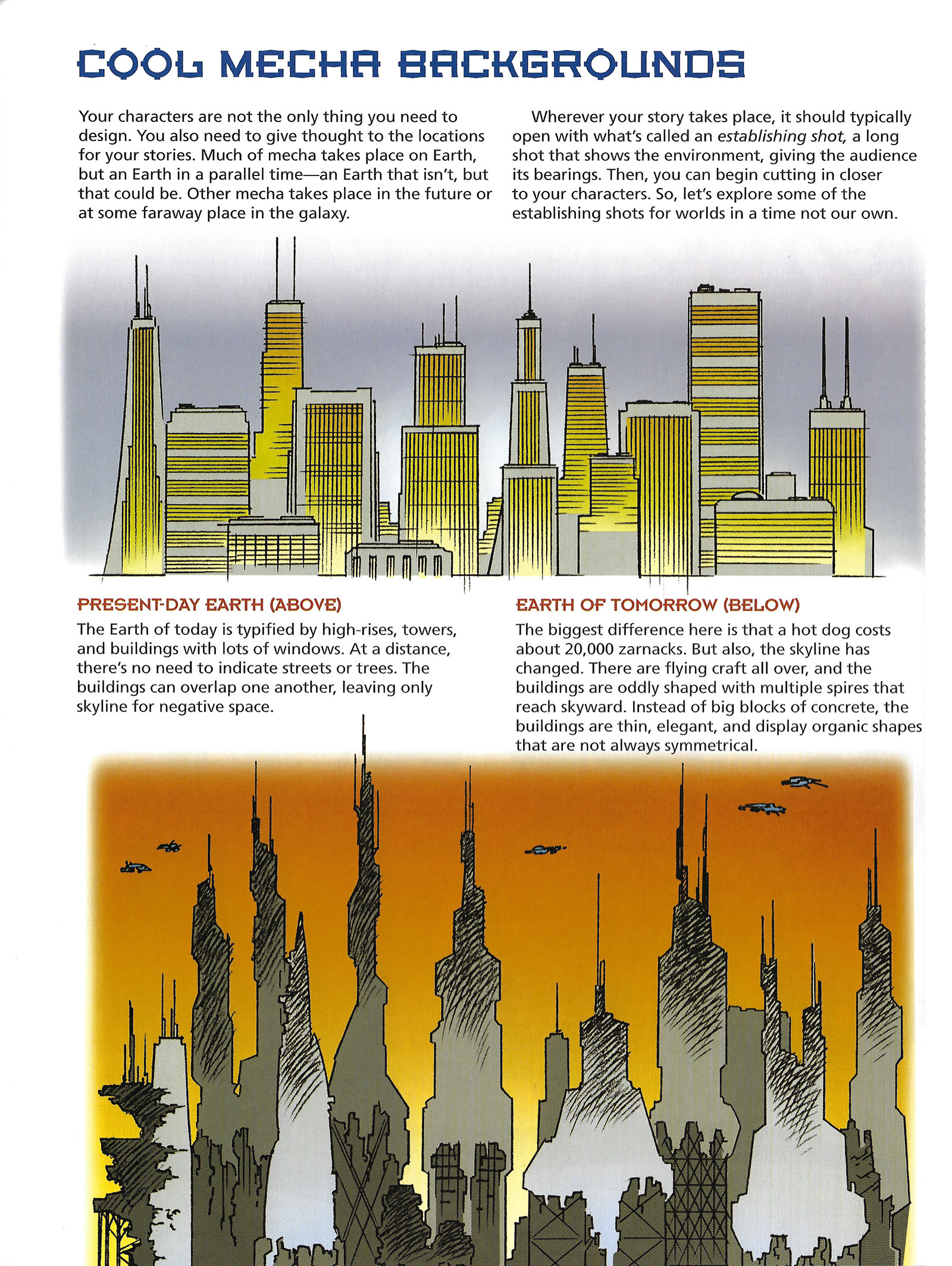

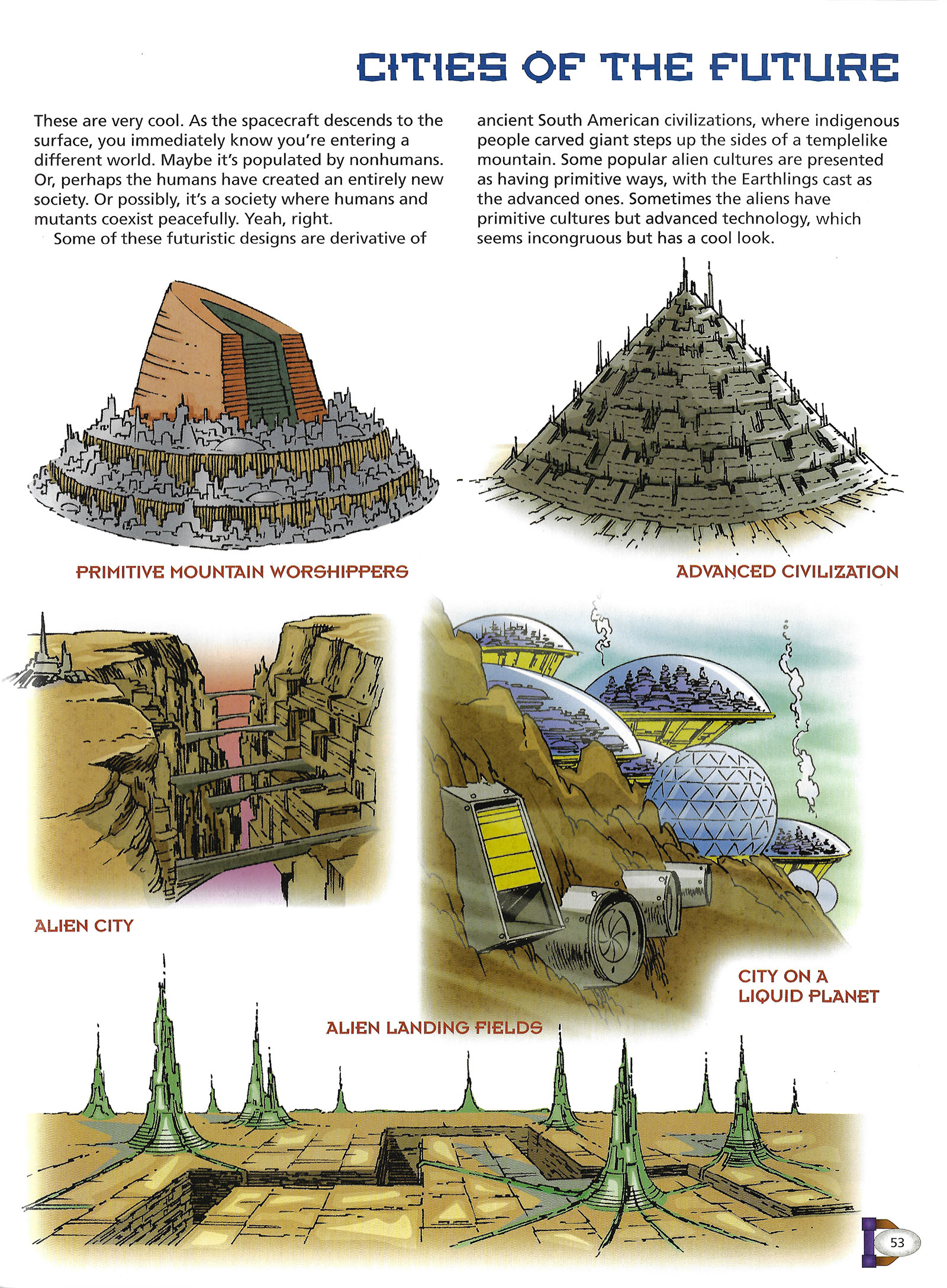

The words “cool” and “alien” are being thrown around a bit much for my taste. It’s the same brand of presumptive labeling I mentioned above. Let’s maybe leave more room for readers to make up their minds, huh?

Better yet, let’s dispense with labels altogether and say something like, “Just as our world is an outgrowth of our historical choices and technological discoveries, so it would be with other worlds. Think about how another species made different choices and discoveries, and imagine how their world would grow from there.”

Teaching is supposed to inspire thought rather than place limitations on it. Right?

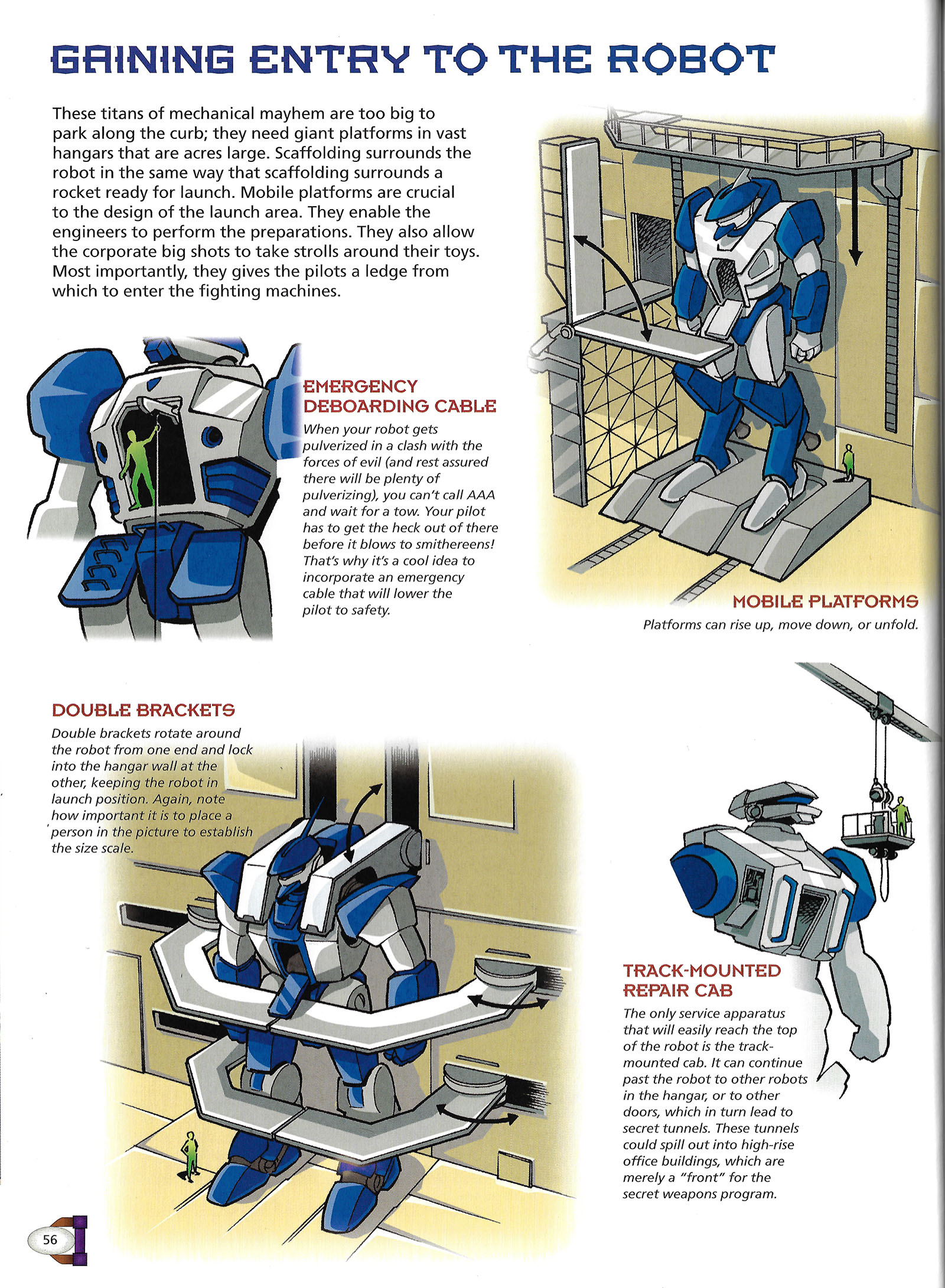

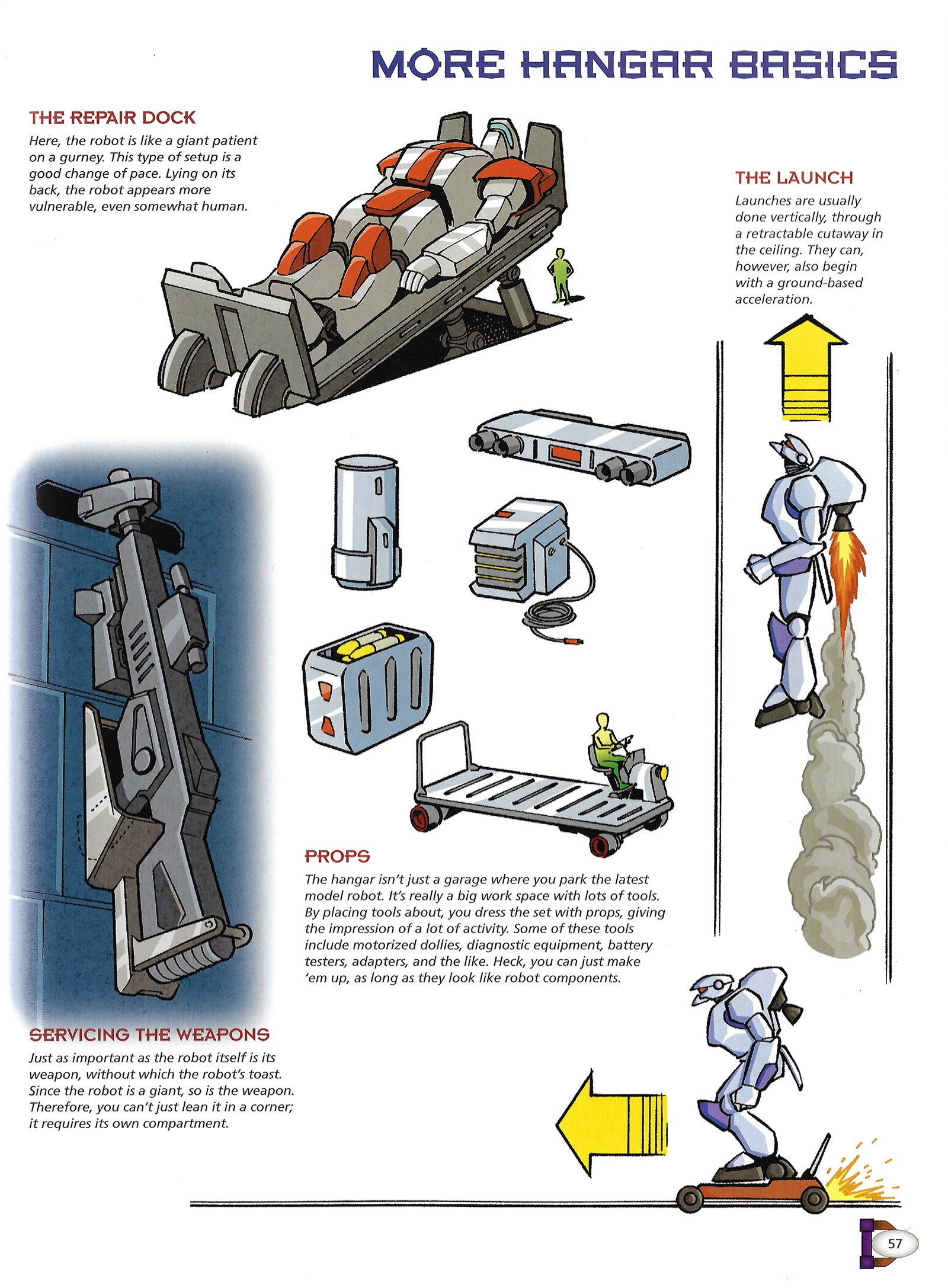

I don’t remember for certain, but this section may have been my idea. If you put a giant robot in a story, it’s important to give it a support infrastructure as you would any other machine requiring human interaction.

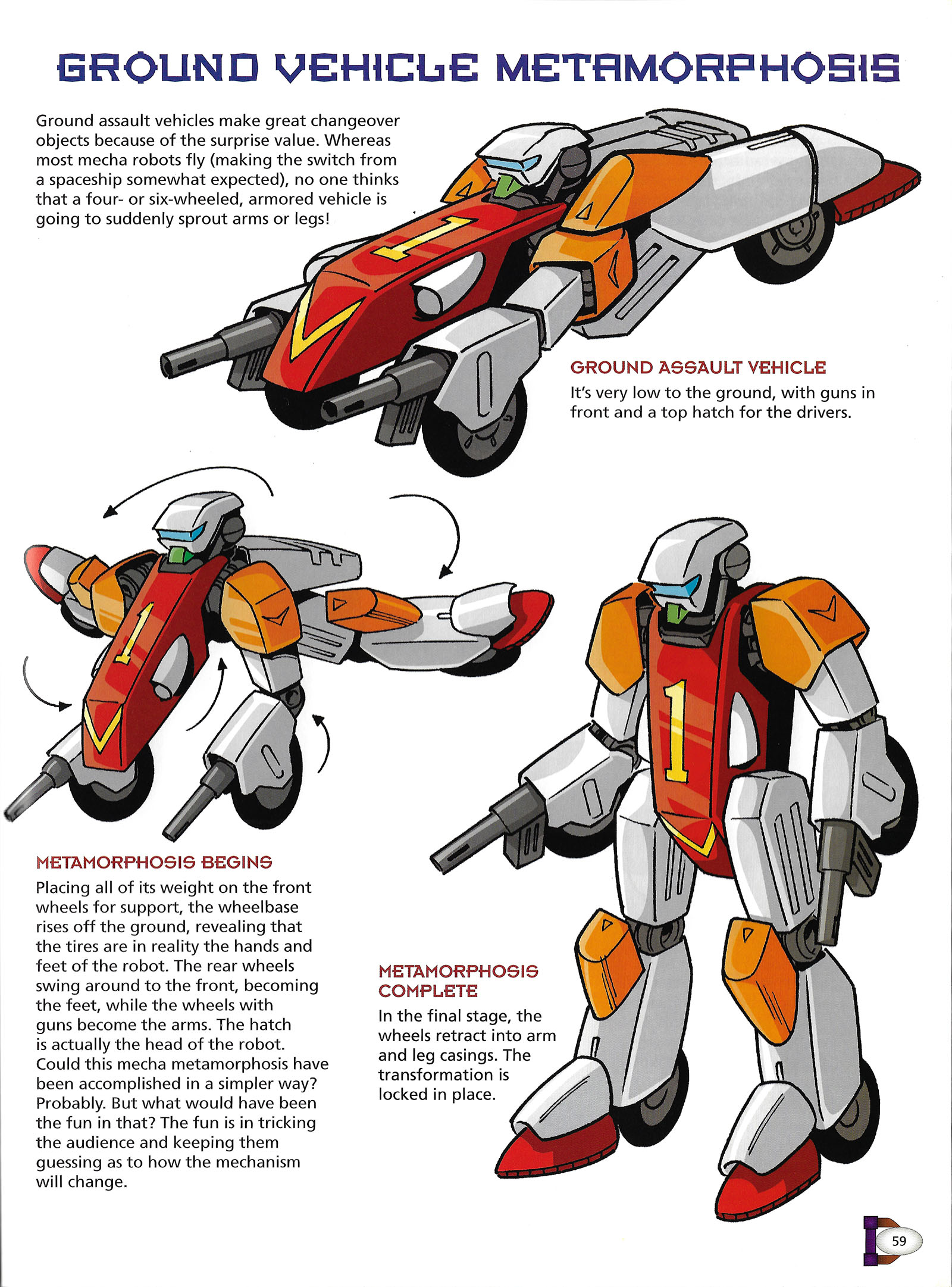

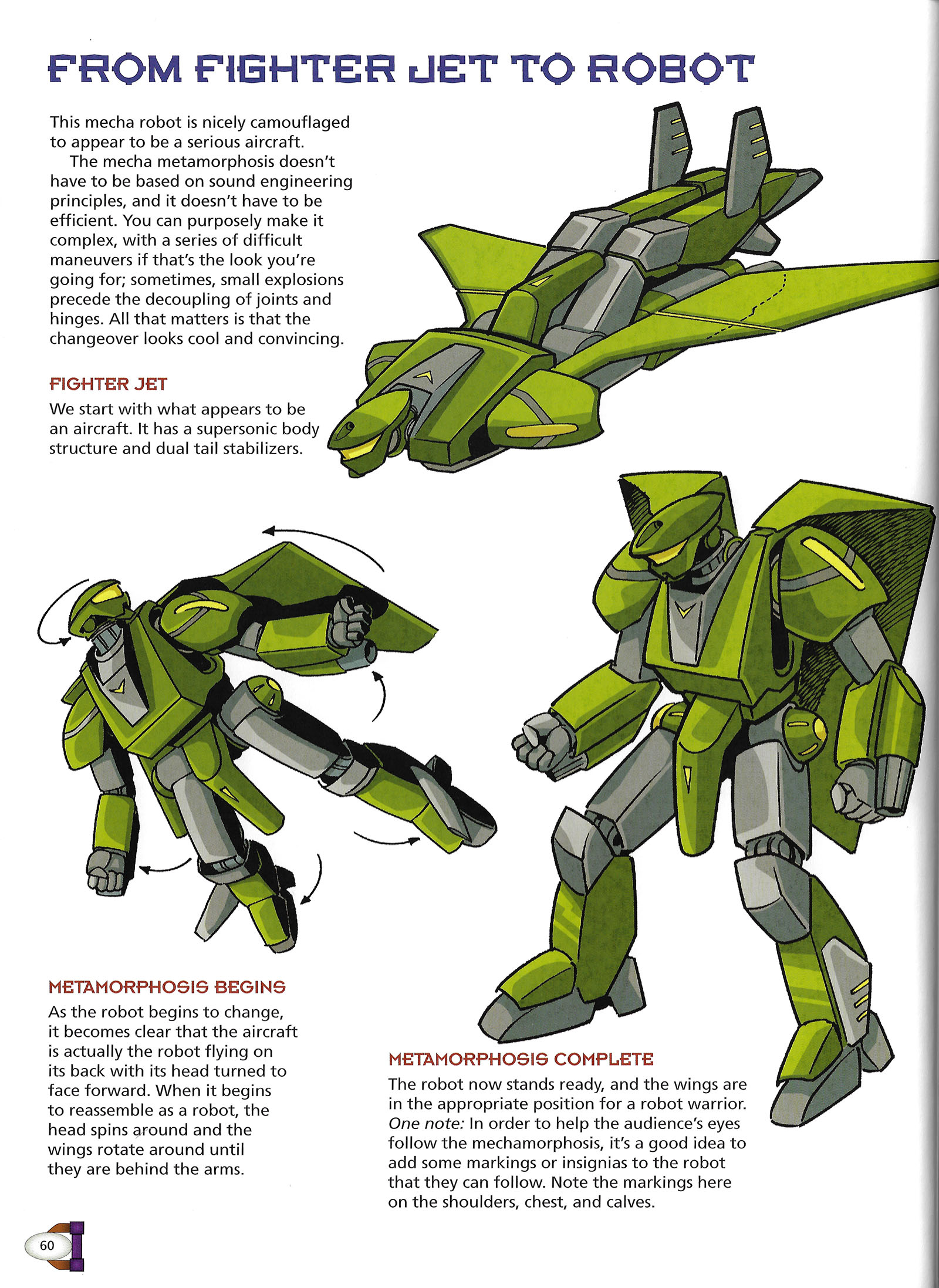

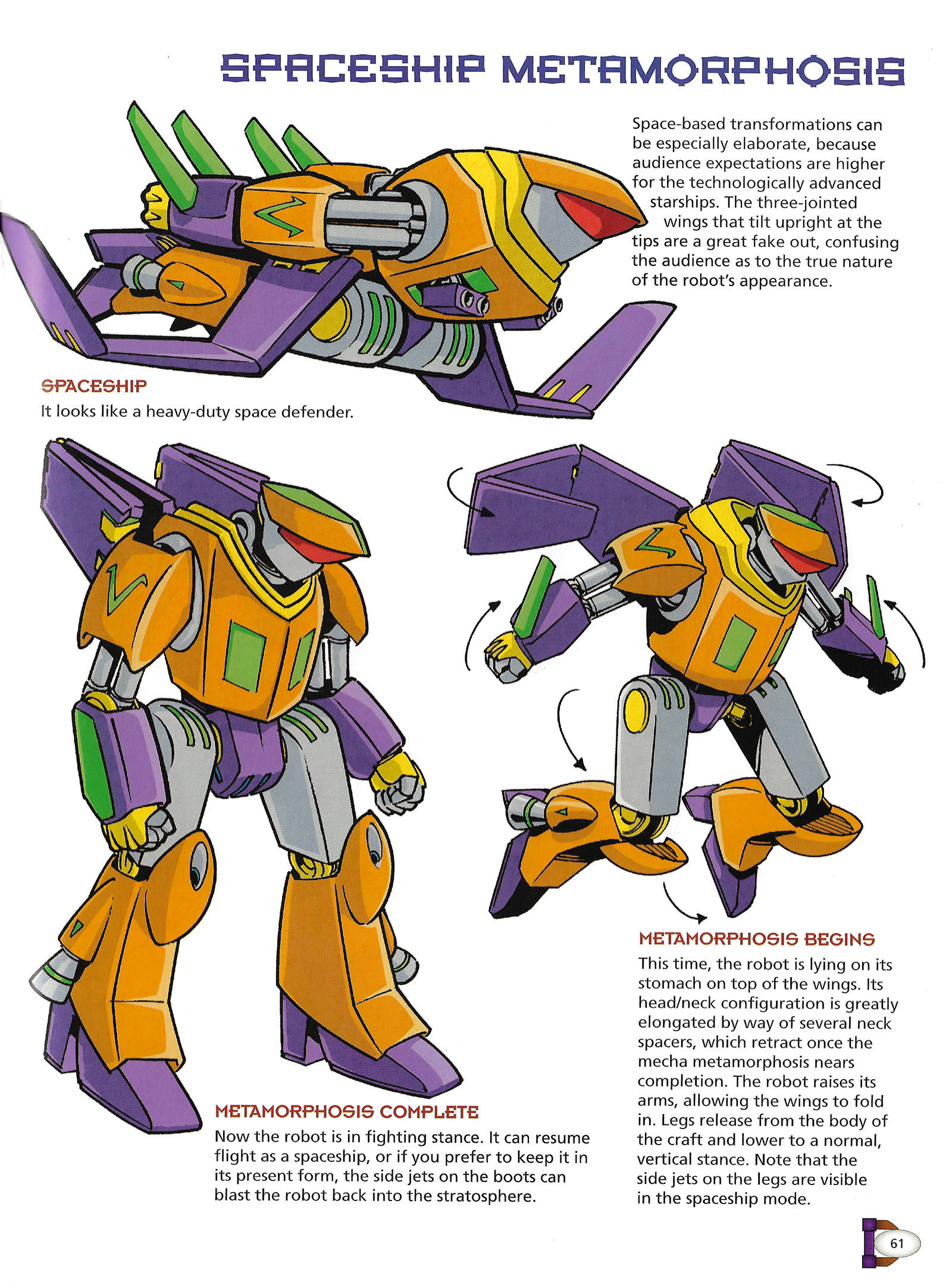

Here’s the final section I contributed to. In fact, I did all of this one.

BTW, the word “Mechamorphosis” was sitting RIGHT THERE. Sigh. Why am I not a millionaire?

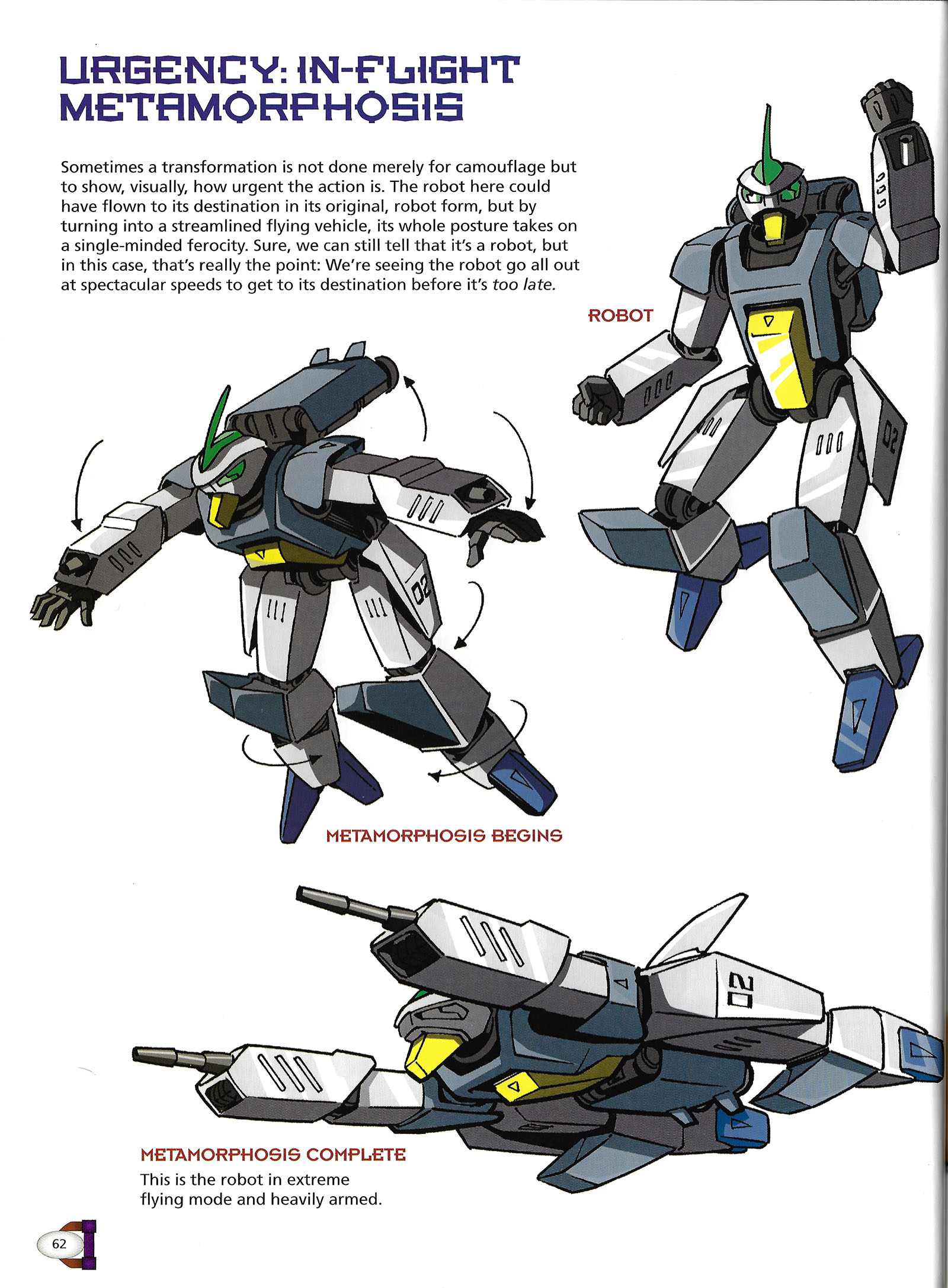

Creating transforming mecha is…hard. REALLY hard. Chris asked me to come up with four different examples without quite understanding what it takes in terms of engineering. Sure, you’re engineering on paper instead of IRL, but it takes a level of supreme genius to design something that looks impressive at both ends, and I wasn’t being paid “supreme genius” wages on this project. It was another red flag that maybe the guy writing this book didn’t know as much as he needed to.

“The mecha metamorphosis doesn’t have to be based on sound engineering principles, and it doesn’t have to be efficient.”

Well, okay, maybe on a live-action Transformers movie, but these are exactly the features that revolutionized transforming robots in 80s anime. HOW CAN YOU NOT KNOW THAT???

I notice that the word “mechamorphosis” showed up in the last paragraph. Bet it was a typo.

Nooooo, space-based transformations “can be especially elaborate” because you don’t have to factor gravity into the process. Come on, man.

Just another example of made-up nonsense in the description. This makes me glad I didn’t work harder to bring these up to super-genius level. All that work would have been flattened by the writing.

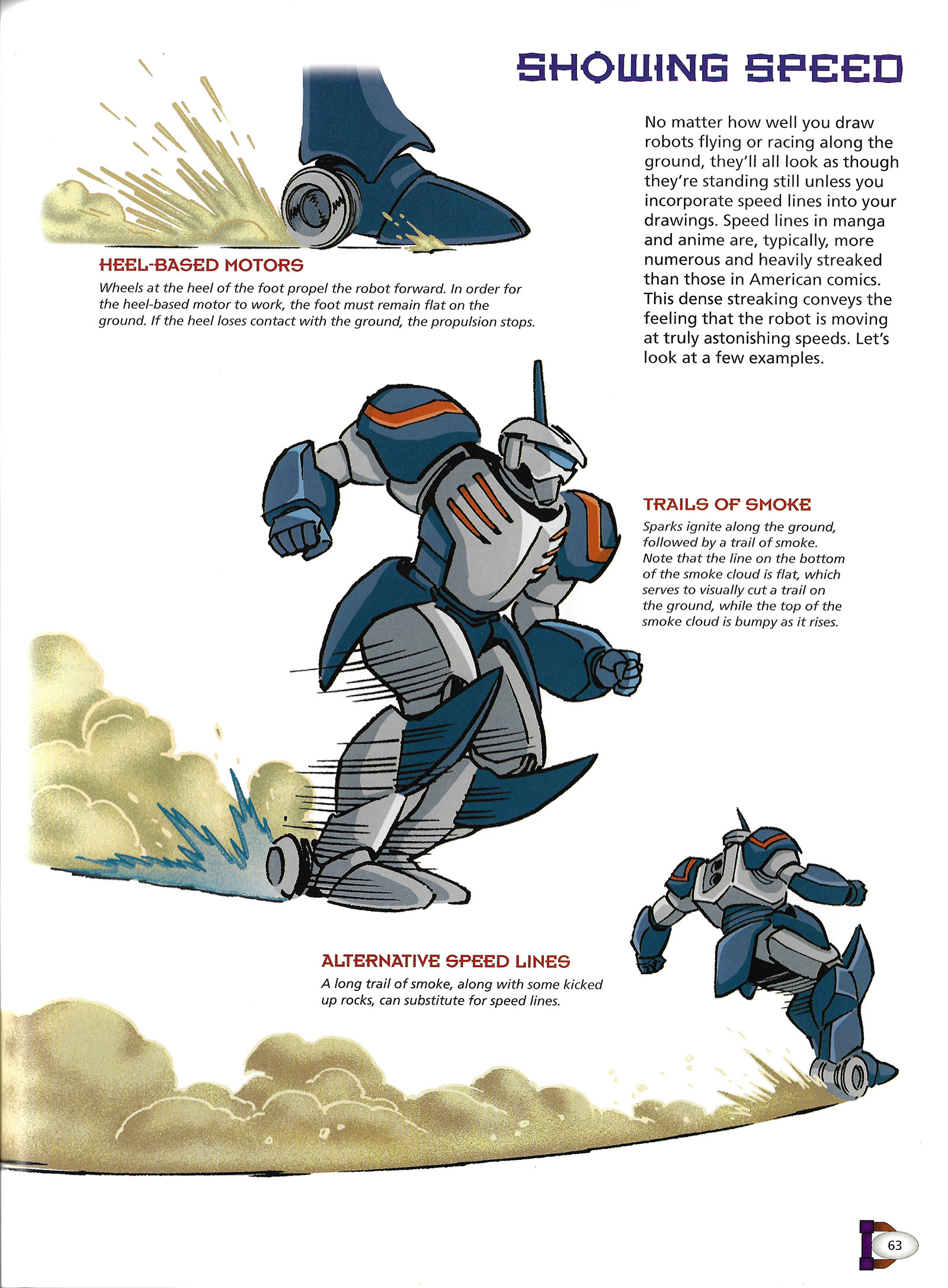

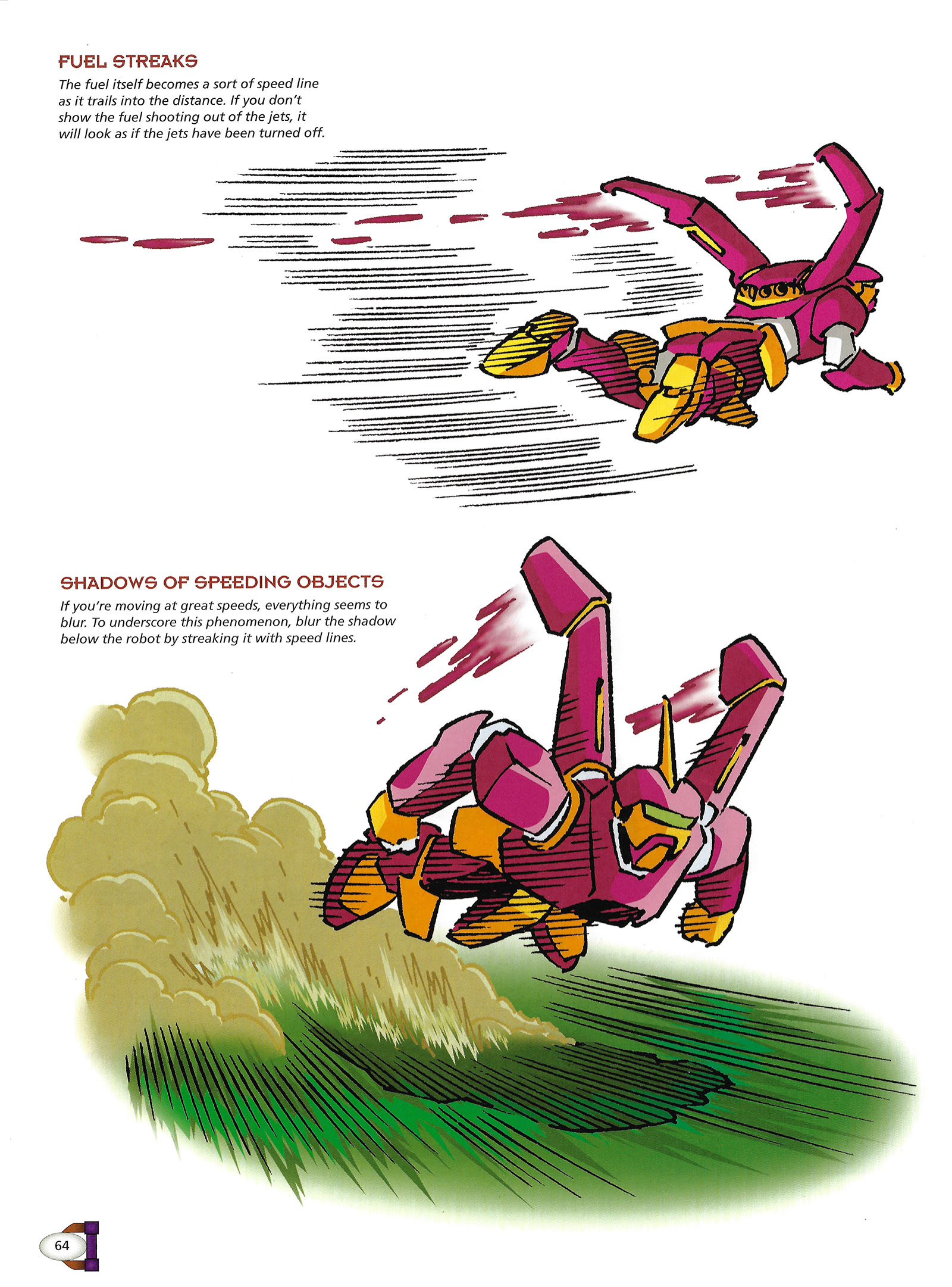

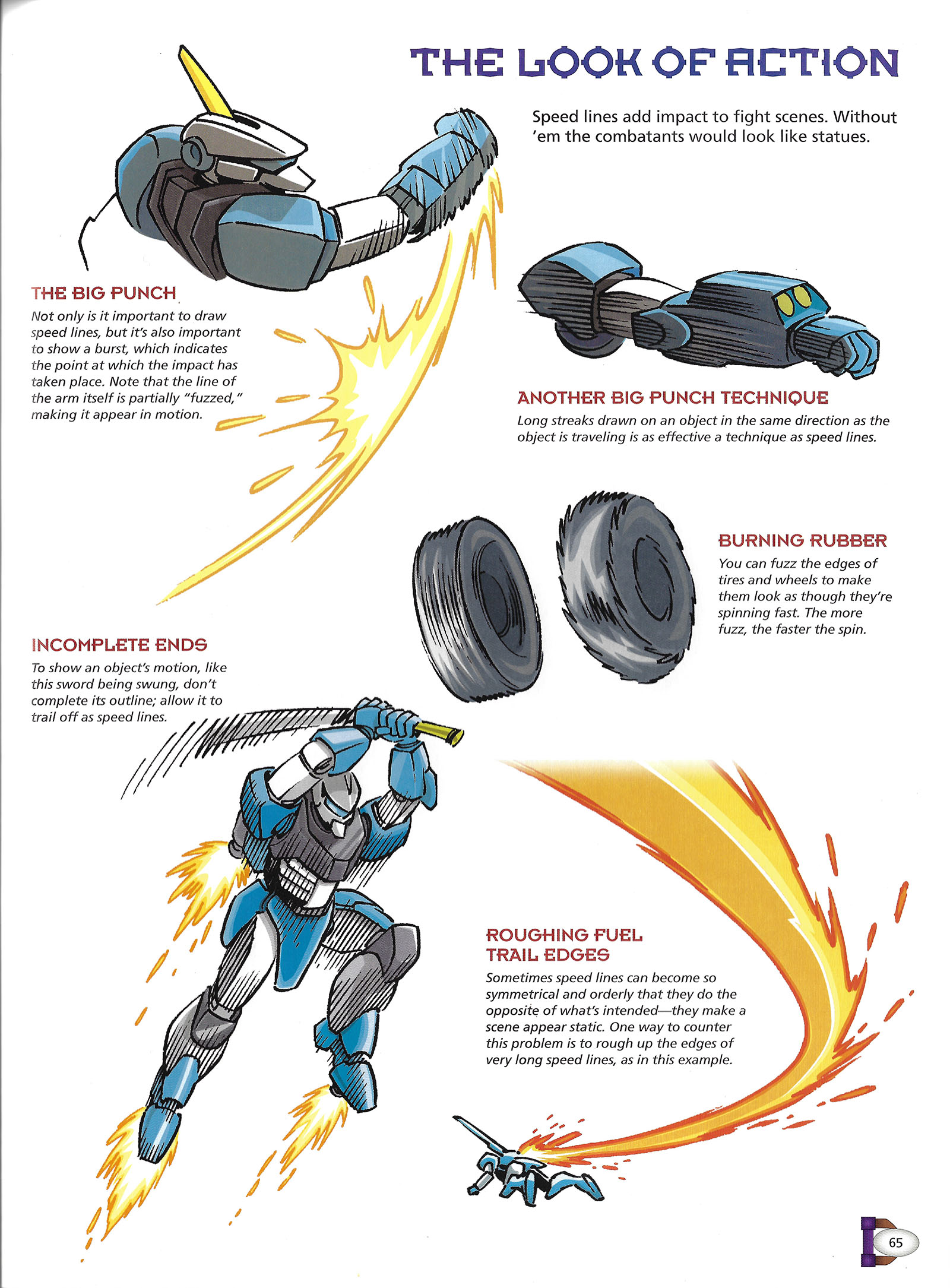

This last portion might also have been done at my suggestion. Where robots go, special effects will follow.

The writing here is pretty much on point. Maybe because there wasn’t much in the art that could be misinterpreted.

This was the final page of the book containing my work, and it went out on a high note. No real complaints about the writing here. But I would have added something about where “speed line” effects actually came from, which was photography and film. Blurring was purely a result of moving objects being captured photographically, and comic book artists adopted speed lines as a way to imitate photographic effects. Manga took that technique and amped it up in many different ways.

I would have liked to see some space dedicated to that phenomenon, so beginners would actually learn something about the process, rather than just copy it in their own work. Rote learning doesn’t teach you how to do anything original. I hope the work I put into in this project got someone to think for themselves. If not, it didn’t accomplish much.

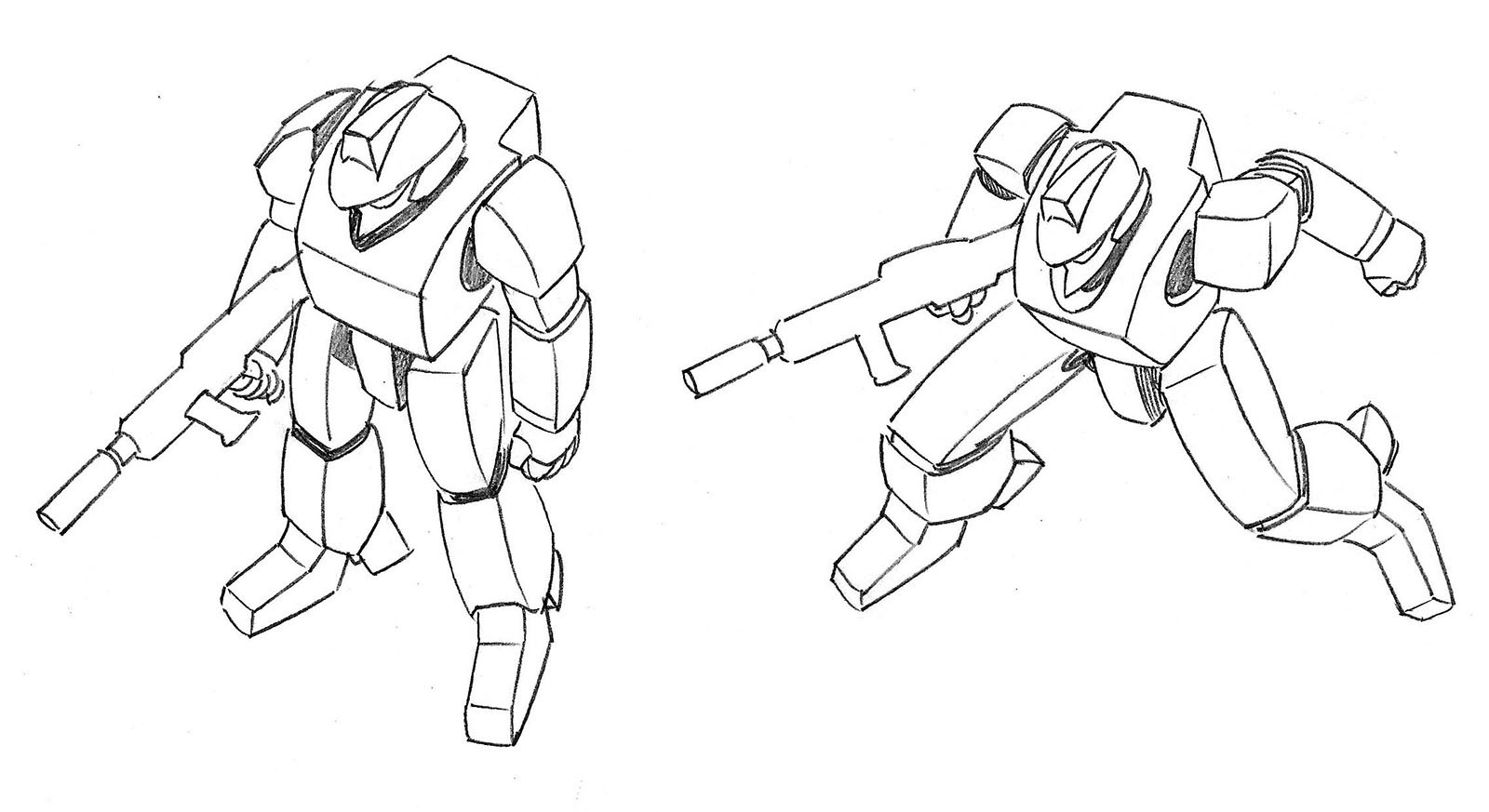

Above and below: unused art. The first piece was a look at how adjusting perspective on body parts can make a huge difference in the impact of a pose.

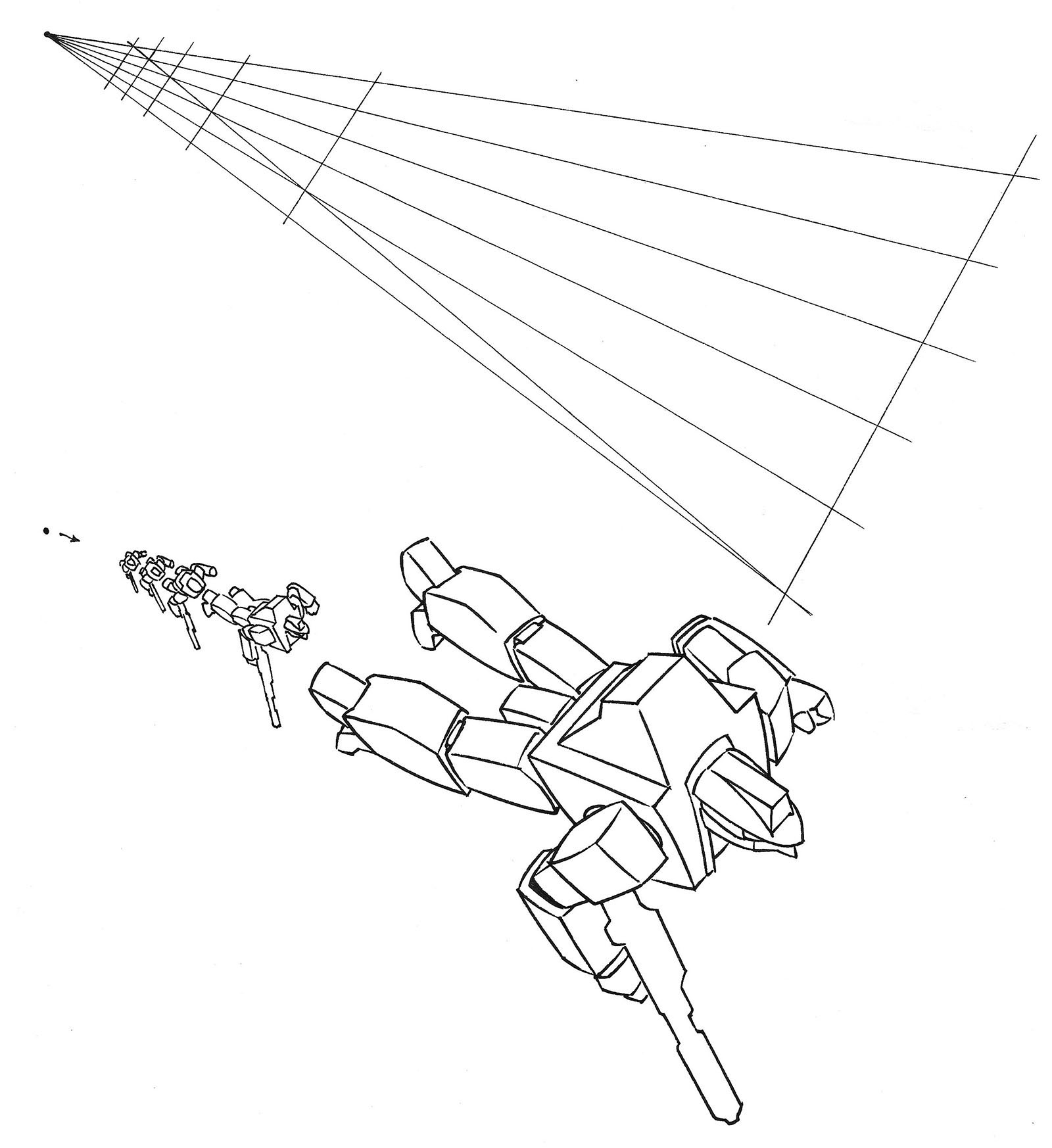

The second showed how to plot out perspective on a moving object. The graph at the top was used to determine how large to draw the flying robot as it approaches us. Not a perfect example in hindsight, but still valuable.