Heavy Gear, 2000-2001

This was simultaneously the most blessed and the most cursed animated TV series I ever worked on.

I’ll start with the “blessed” part, because it’s an amazing tale of causality that shows what can happen when you follow your bliss.

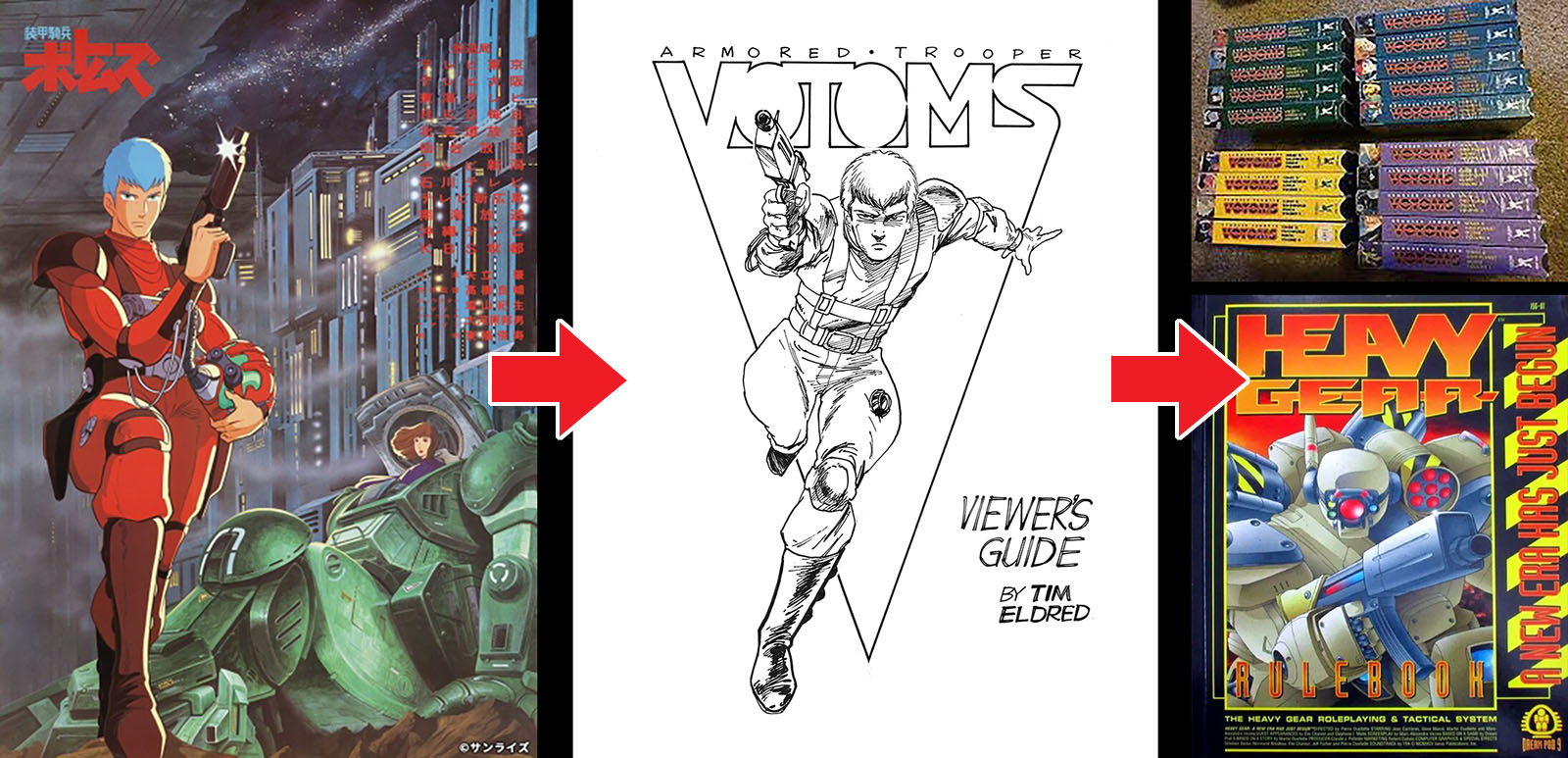

In the mid 80s, my bliss was “Real Robot” SF anime from Japan. This genre was on fire back then, producing another TV series to investigate every five minutes, and I couldn’t get enough. Very briefly, “Real Robot” describes mecha designed to follow the laws of physics, at least moreso than the “Super Robots” of the 70s. During that time, the “Real Robot” show that rose above all the others for me was Armored Trooper Votoms.

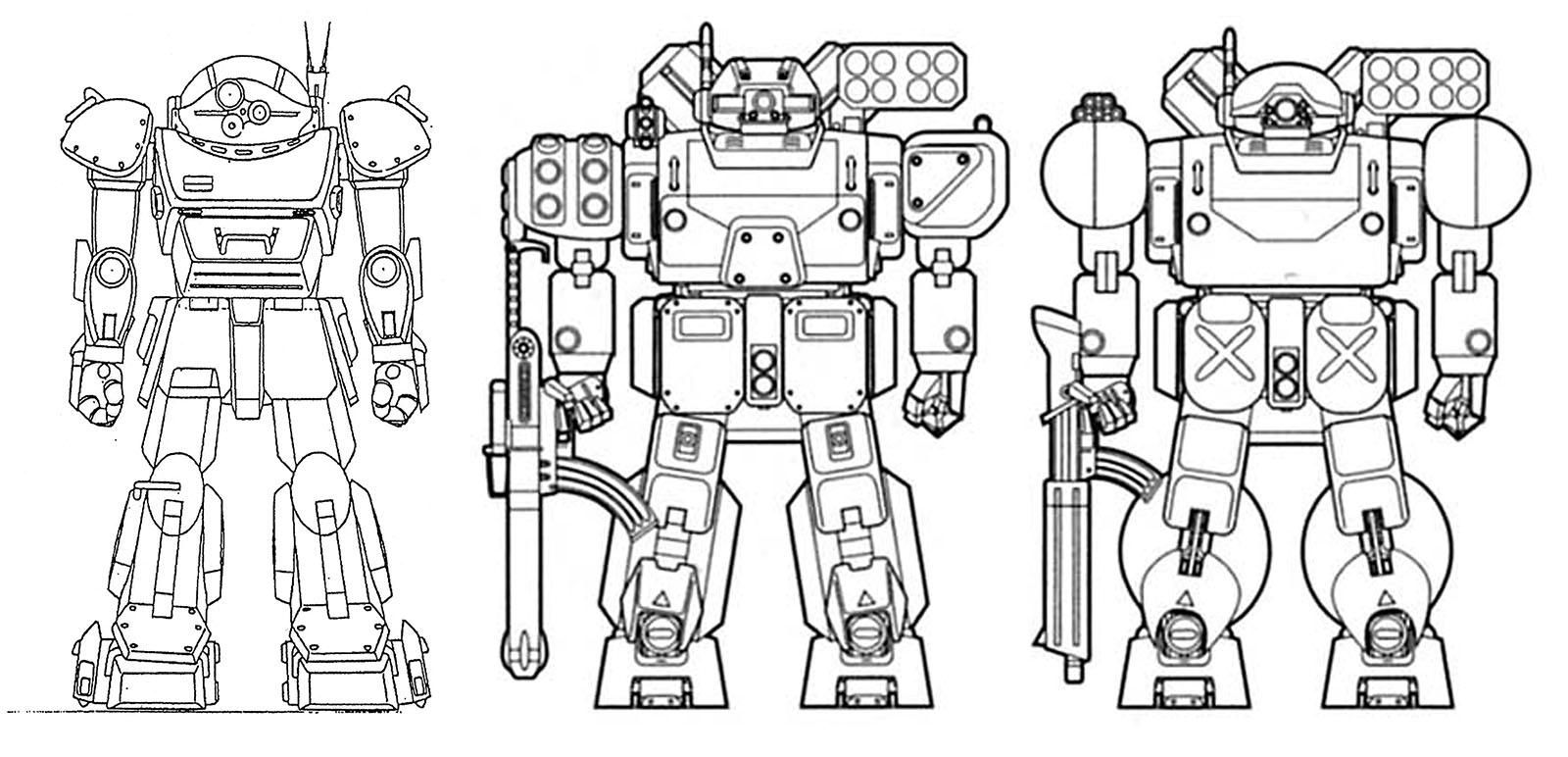

Votoms debuted on TV in 1983, and I started seeing pieces of it the following year. It had everything I was looking for in SF anime, including the most grounded, realistic robot designs ever seen. The designer, Kunio Okawara, wanted to create something that looked like it came out of a factory here on Earth, and could be interpreted as toys and models without modification. He did it so well that these robots – called Armored Troopers – are still a pinnacle of mecha design in the anime world to this day.

Votoms inspired me so much that I felt driven to write about it. Nothing was available in English yet, so I consulted with translators, collected books, studied details, and put everything I learned into a huge fanzine called The Votoms Viewer’s Guide. I debuted it chapter by chapter in an APA (see what that is here) and kept at it for years, finally finishing it in 1991. This was no ordinary ‘zine; I was a professional graphic artist during those years with access to high-end production equipment. What I produced approached magazine quality with carefully-curated images. (See it here.)

This is important, because when my Viewer’s Guide began circulating in fandom, it caught a lot of eyes. Many unexpected things happened as a result.

When eyes at Central Park Media landed on it, the ball started rolling for them to import the anime. When I met with them to talk about it, they specifically told me it was my work that inspired them to pursue the license. In 1996, Votoms arrived on VHS in America, and CPM hired me to create print media projects for them, including the first and only Votoms graphic novel – literally a dream come true. (See it here.)

That would have been payoff enough, but there was more to come. A Canadian-based company named Ianus Publications also got a copy of the Viewer’s Guide and it inspired them to pursue the rights for a Votoms role-playing game. (I had some involvement with Ianus when they published one of my original comics, which can be seen here.) They created a scenario based on the anime and put together a pitch for Sunrise, the Japanese studio that owned the series.

Sunrise turned them down, which was disappointing, but the minds at Ianus had put a lot of work into their pitch and didn’t want to see it go to waste. So they put it back in the oven and made some modifications. By 1992, they’d changed their name to Dream Pod 9 and got more heavily into game production. Two years later, they finally brought their revised Votoms game to market under the title Heavy Gear. It was as close as you could get to Armored Trooper Votoms without calling it that. The backstory was different, but you could map a “Gear” over an Armored Trooper and they pretty much had the same skeleton (see below).

Heavy Gear found its audience and flourished throughout the late 90s, shifting back and forth between analog and digital. As it grew, wheels started turning.

And now we find ourselves in 1998. It was my second full year at Sony Animation Studio, and I was promoted to become the supervising director of a PBS Kids cartoon called Dragon Tales. Being assigned to that show kept me from working on the studio’s first CG sci-fi series, Starship Troopers: Roughnecks (based on the 1997 live-action film). I voluntarily wrote a concordance for the franchise that became the basis for the series bible, but there was nothing else I could do, so I drew preschool dragons for a year and a half and waited to find out what would come next. When I finally did, you could have knocked me down with a finger tap.

Sony’s next show was going to be Heavy Gear.

I immediately went to our Exec Producer and told him a shorter version of everything you just read and practically begged him to put me on the show when Dragon Tales was over. He had no reason to say no. It would put me back under the wing of Audu Paden, the supervising director on Extreme Ghostbusters and Godzilla, and he was happy to have me on board. I simply could not believe my luck. My devotion to Votoms was the first link in a chain of events that culminated in this moment. It was happening because of a decision I’d made long before I met any of these people. And now it would be my job to direct episodes of the closest-to-Votoms TV series that could possibly be made outside of Japan.

The client for the show, the company actually holding the purse strings, was a syndicator named Bohbot Kids Network (BKN). They’d backed some of Sony’s previous shows and were in again for another 40-episode package. I would be reunited with many of the crew I’d worked with before, plus a few new members. And it was going to be my first (of many) CG series.

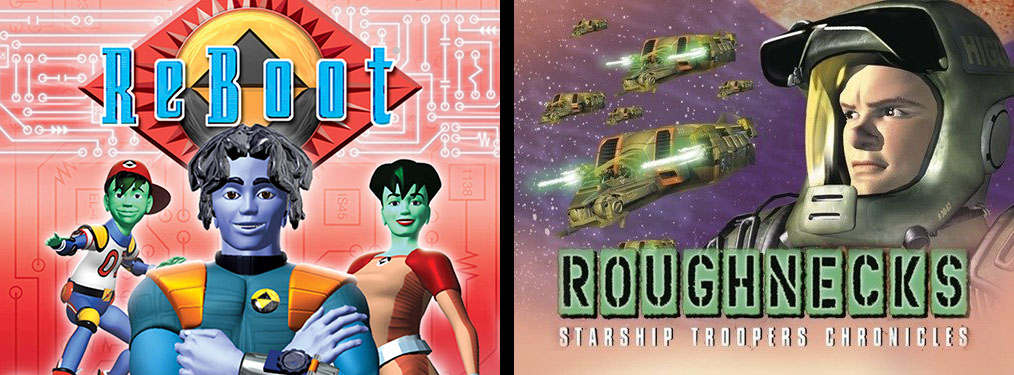

Roughnecks had broken major ground in this area. Prior to that, the only all-CG TV series that had made waves was Reboot (1994), made by Mainframe Studio in Vancouver, Canada. It was just one step up from a computer game, but it looked like nothing else on TV. Roughnecks was the next show to attempt CG on that scale with animation by a studio named Foundation. The plan was for them to continue as a partner on Heavy Gear, but for reasons to come, Mainframe ended up taking their place.

I could go on all day long about the different demands of 2D and CG animation, but for the sake of this article I’ll sum it up as briefly as I can. 2D animation comes down to how many images the human hand can draw in a given time. CG comes down to how many images a computer can render in a given time. Everything works backward from those limitations. In 2D, you make creative decisions that avoid excessive drawing. In CG, those decisions are driven by the need to reduce strain on a digital pipeline. In both cases, you discover ways of convincing a viewer that they’re seeing more than they really are. Each medium has its own advantages and pitfalls, but with both it’s a matter of manipulating illusions.

I was very fortunate to start Heavy Gear with a thorough working knowledge of what the robots could do and how to draw them, because I had a LOT to learn about the limits of CG. In my head, I was the luckiest boy in the world, being paid to draw a Votoms cartoon in storyboard form. In the actual production world, I was being pushed down what felt like a narrow gauntlet of new rules.

I’ve done a lot of CG shows since then, and it’s become second nature, like flipping a switch. But every rule I now know by heart had a painful lesson behind it. And it’s at this point that I have to start edging toward the curse.

The production plan for Heavy Gear, which commenced in early 2000, was Sony’s most ambitious one yet. I was one of ten directors assigned to the 40-episode series, and each of us had 3-4 storyboard artists on our team. These days, a crew that size is unheard of. Even at the time, it was an awful lot of people for Audu Paden to manage. But he had brought all of us up through the ranks of his previous shows and trained us to handle just about anything. If it all went to plan, each team would get four episodes and all the storyboards would be done in less than a year.

The story premise was equally ambitious. The setting was the colony planet Terra Nova in the far future, where the two factions of North and South are in constant friction. This would play out in a tournament of clashing robots (“Gears”) in a variety of extreme sports settings over the first ten episodes, then the story would get progressively bigger. A war would break out between the two factions, then they would be forced to call a truce when an outside force (from Earth) attacked Terra Nova. Former enemies would have to become allies and learn to cooperate.

It sounded very promising to me, and felt a lot like Votoms, which also started out with arena fights and grew into a much larger epic on a Star Wars scale. My one regret going in was that I’d only get to direct four episodes. But I was 100% ready to participate.

The first arc proceeded as planned. We had two teams of Gear pilots: The Shadow Dragons (south) and the Vanguard of Justice (north). Five pilots on each side, plus a few supporting characters. The lead Shadow Dragon (voiced by Michael Chiklis) dropped out of the tournament in the first episode, turning over his Gear to our main character, a teenager named Marcus Rover. The Dragons were sort of the good guys, even though they were a little goofy. The Vanguard were thorough villains, cruel and obnoxious. All ten pilots were introduced in Episode 1, which made it kind of a mess. I would have brought them in gradually over the first four or five episodes, giving each one time to plant their flag for the long haul. But nobody asked me.

I had built a ton of Votoms model kits and drawn a Votoms comic book by then (it still amazes me that I can say that), so putting the robots through their paces came naturally to me. I introduced Votoms to the entire crew, hoping it would help them grasp the physicality of the mecha, but I don’t know how many of them took it to heart. In a way, it kind of didn’t matter, because we were all on a collision course with a fatal moment where the entire plan would collapse.

Before we knew what was happening, the curse was upon us.

One day, as my team and I were toiling away on our first show (Episode 4), I was called to Audu’s office urgently. Five other directors joined me. Audu wasn’t there, but his assistant closed the door and turned on the speaker phone. It was Audu in his car, on his way back from an important meeting that had just taken place.

“This information is not to the leave the room until I get there to announce it in person. You guys are now the crew.”

We looked at each other, trying to figure out what we’d just heard. Audu enlightened us. Bohbot had run into financial problems that forced a radical change to the framework of the show. They were still committed to 40 episodes, but they had scrapped the story plan and wanted to stay within the “extreme sports” format of the first ten episodes. We were no longer building up to anything bigger, just running in place. The reduction in budget forced Foundation to pull out of the project (creating the opening for Mainframe) and reduced our ability to create new assets.

Another thing that had to be reduced was the rest of the crew. After Episode 10, it would only be the six of us, each storyboarding our own episodes as a solo act. Everyone else was about to lose their job.

It was a lot to take in. Nobody was happy about it. Spirits dropped. Everyone from the executive producer on down had lost the chance to make something unique and dramatic. Now it would be just another show with not much to say. We sort of had a wrap party for the departing crewmembers, but it didn’t feel like much of a show, since most of them had only worked on one episode.

For me personally, it was a mixed bag. I could certainly handle the workload, and I’ve always found it very satisfying to steer an episode by myself. But it’s a lot more fun to collaborate with other artists and strengthen each other’s work. Esprit de corps makes everything more enjoyable. But it was not a priority for our client.

Another thing that got lost in the reshuffle was a toy line for the series. Someone had signed on to make action figures of the robots and we all got to see wax prototypes one day at the studio (the only existing photo is shown below). But now they would never progress beyond that. It was hard not to feel like we’d been on a train bound for Futureville but got rerouted to Dumbtown instead.

That said, thirty more episodes of Heavy Gear stretched out before us, and there was no time to moan. Metal had to be mashed.

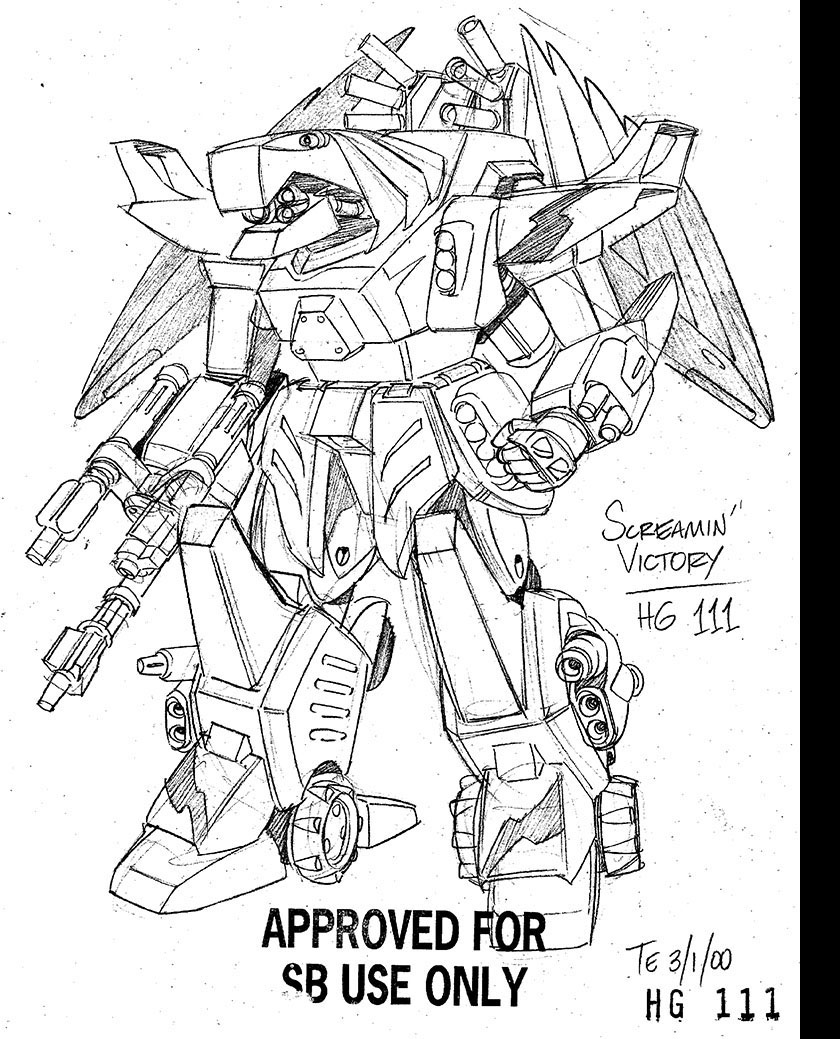

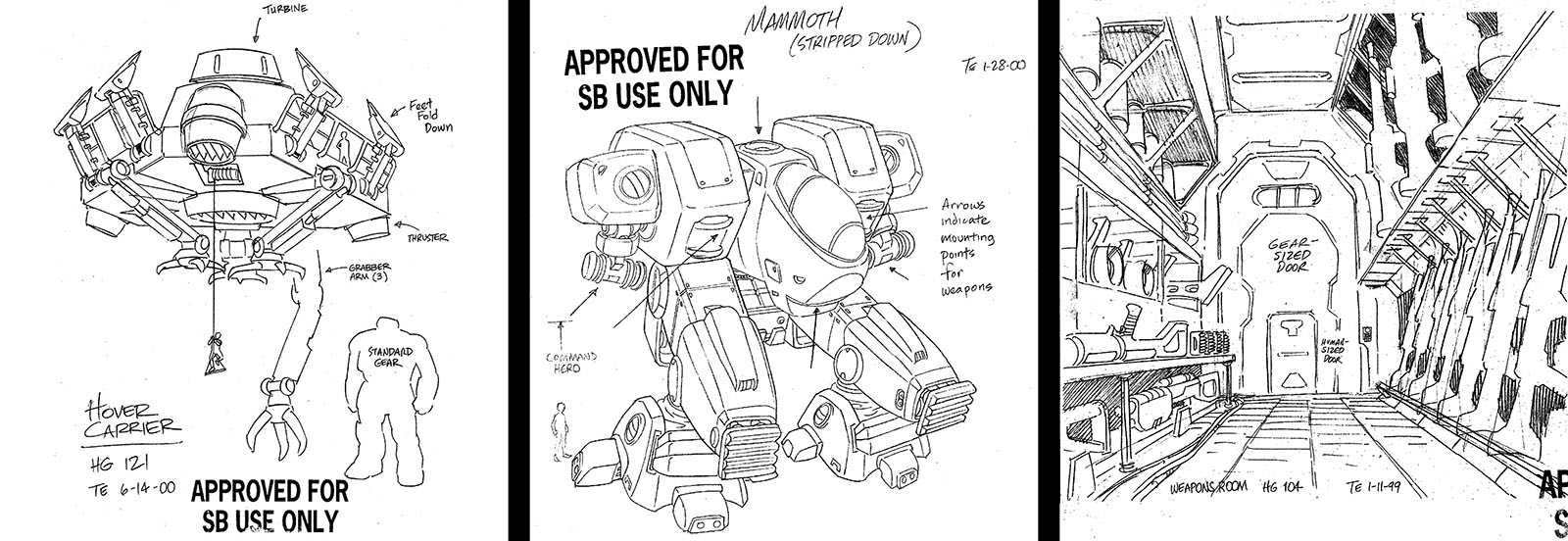

The stripped-down second phase of the production had blessings and curses of its own. On the upside, it was very easy for me to pretend I was still drawing a Votoms show. I had full control of every aspect of it, and I was right in my element; SF action with mecha. The characters became extensions of me, thinking strategically in combat. (Except I had the advantage of thinking in extreme slow motion since a second of screen time could take several minutes to draw.) I also got to design a lot of the props and sets needed for my episodes, including more of that juicy mecha.

On my best days, it was like I was born to make this show. No matter what the scripts threw at me, I could bring it to life. High-speed chase? Easy. Zero-G space battle? No sweat. Team on team brawl? Bring it on. What’s more, once I set a pace for myself, I never even had to work a full 8-hour day to make my deadlines. I kept asking for more, but there just wasn’t more to do. All of this propelled me through a total of nine episodes, more than any other director.

Sounds like a dream come true, right? Here’s where the curse comes in again.

As I mentioned above, I had a lot of hard learning to do when it came to CG. My experiences on previous (2D) shows taught me that the finished animation would never match my storyboards 100%, but at least I could still see my storyboards underneath it. The structure was sound. Not so with CG. In this case, the storyboards were treated as a starting point. When they went through the motion capture process (with actors on a stage), the structure shifted significantly. All that careful work and intricate drawing could be completely discarded.

I was confronted by the reality of this the first time I saw finished footage. It was still recognizable as the show I worked on, but in many cases there were things in it I’d never intended. Either the CG director changed a scene on the fly or some limitation of the medium forced a compromise that pushed it in a different direction. At first it felt like a betrayal. It was the same for all of us; the finished product was so divorced from our storyboards we wondered what we were there for.

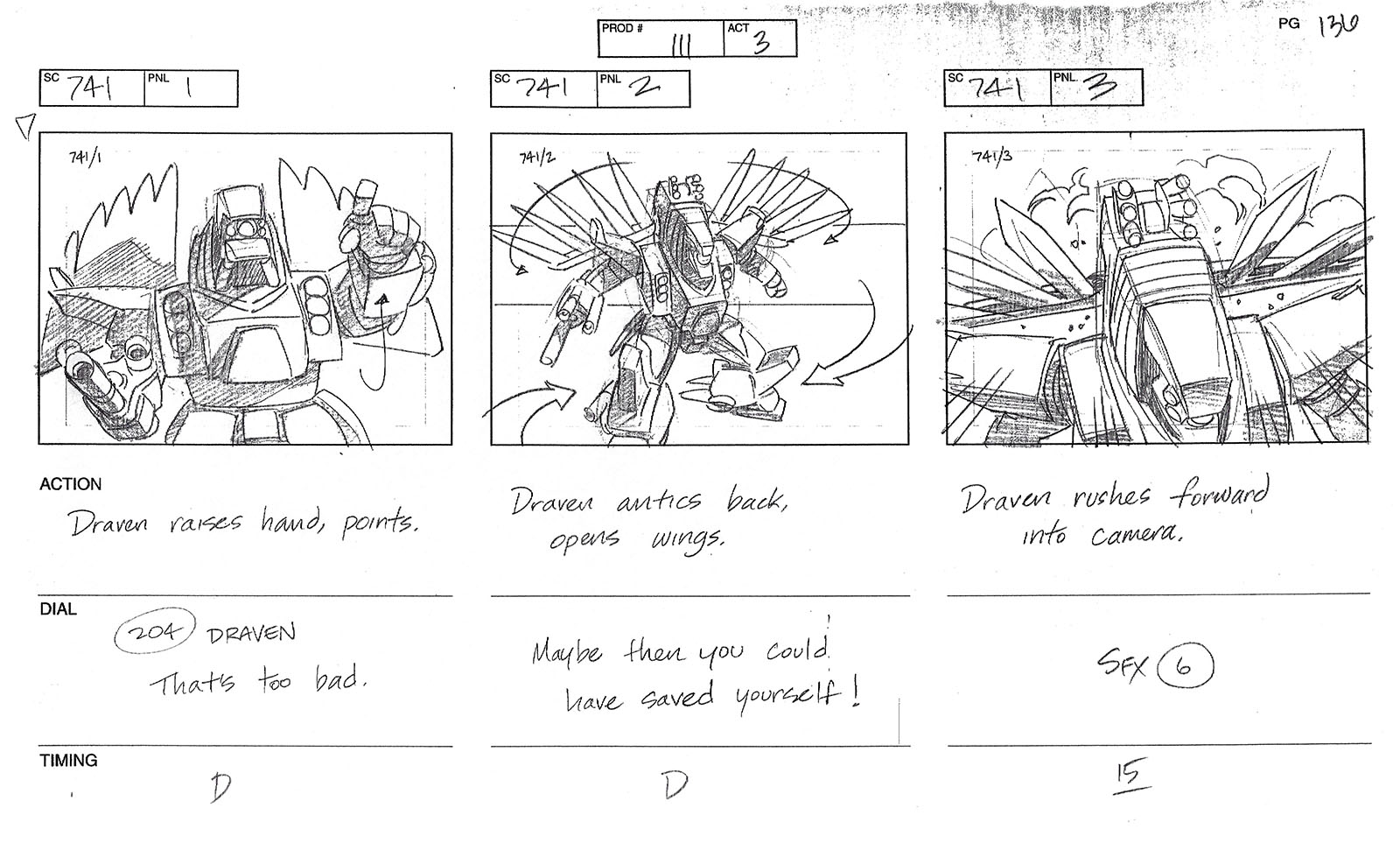

The worst moment came when I saw footage for my second episode, titled Disqualified (show 11). It was the first one I boarded all on my own, and I put my soul into that thing. On every series I’ve done, there’s been at least one “magic storyboard,” where it feels like my hands are being guided to draw all on their own, and I’m just a spectator. The “magic storyboards” are always the best ones, emerging fully formed and rock solid in the first draft. I even got to design a new enemy robot (above) and work out all of its capabilities, making me the real-life animation mecha designer I always wanted to be.

Then the curse struck again: when the footage came back, all the soul and magic was drained out. I hated it so much I considered not taking a director credit. Later, I turned down an invitation to participate in the DVD commentary because I couldn’t trust myself to speak politely.

The look of the CG models also took a lot of getting used to. When you storyboard a 2D show, you’re using the same designs the animators will use later. In CG, those designs can change significantly. Props and mecha will look pretty much as you expect, but characters can be a whole different ball game once they’re sculpted as models. On average, I thought they looked awful. Like Mego dolls with no mass. Everyone and everything moved around way too much, giving it a weightless feeling that not even sound effects could counteract.

And here’s the thing; these critiques are accurate, because that’s exactly what CG is; zero-G puppetry with virtual marionettes. The more money you have to throw at it, the more you can spend on techniques to disguise it. You could get that kind of money together for a feature film back in 2000, but many years would pass before the techniques got cheap enough for a TV budget.

In the end, it was a harsh reminder of the cardinal rule in TV animation: there’s the show in your head, and the show that ends up on TV. They are not the same thing. But the viewers only know what’s on their screen. So that’s the show that matters.

And yet, every single time I revisit something I made, the show in my head is still there, impossible to ignore. That wasn’t just the curse of Heavy Gear, it’s the curse of TV animation itself. I don’t know if it can ever be lifted.

Heavy Gear debuted in syndication September 2001 (there’s that curse again) and as far as I know it ran all the way through until it was done. Two DVDs were released in 2002 with five episodes apiece, and I got an episode on each one. A set of the first 13 episodes was released in the UK, but that was the end of it. The rest remain unreleased, and the show is not currently streaming anywhere. So this right here may be the most Heavy Gear series content you will find online.

Columbia Tristar, 2002

Contains Episodes 1-5

Columbia Tristar, 2002

Contains Episodes 7, 9, 10-12

Sony, 2004 (PAL format UK edition)

Contains Episodes 1-13

EPISODE LIST

I directed the ones indicated in red

The last four episodes were all clip shows

2. The Face-off

3. Training a Dragon

4. Grudge Match

5. The Desert Duel

6. Gear Wars

7. The Train

8. Sacrifice

9. The Tunnels

10. Mega Duel

11. Disqualified

12. Marcus Rover, Northern Ace

13. Mercenary Gambit

14. Power Play

15. Transformation

16. The Monster of the Maze

17. The Scavenger Hunt

18. Ultra Duel

19. Under Orem

20. Gear Scout Jamboree

21. Rolling Brawl

23. Close Encounters

24. Under Water, Under Seige

25. The Zero Racer

26. The Spider’s Web

27. The Big Roundup

28. The Rise and Fall of the Heavy Gear Empire

29. Space Race

30. Gearassic Park

31. Heavy Gear Smashdown

32. Tournament Extreme

33. The Vanguard Storm

34. When Gears Collide

35. The Most Dangerous Gear

36. Gear-Lympiad

37. Marcus Rover Highlights

38. Of Monsters and Mayhem

39. The Third Degree

40. Gears of Fire

Episode 3 on Vimeo

(the only one I could find online)

The Magic Storyboard

Hi Tim – this is a fascinating read, thanks for sharing.

I’ve been a fan of Votoms since I stumbled across a Scopedog model kit at a comic store here in New Zealand some time around 86/87.

I knew Starblazers and Robotech of course but the Scopedog was something special, it was realistic and believable. It which made me go looking for more info (damn hard to do without the internet back in the late 80s) and somehow I stumbled onto the Kummen Jungle arc of the series on VHS from a Japanese store and got hold of a copy of your Votoms Viewers Guide which really helped. Years later I found the Heavy Gear RPG and instantly thought of Votoms. Later I got the the official English subtitled series on VHS and the R.Talsorian Votoms RPG which contained so much of your work.

Votoms is my all-time favourite anime and sci-fi story. In my office right now I have various Armoured Trooper models and a whole bunch of unbuilt Votoms kits. Sadly, I wasn’t allowed to name my daughter Fyana but I did try!

Thanks so much for your work on bringing the series to an English speaking audience.

You should have asked for Fyana as your daughter’s middle name. That’s how I got it approved!

Dammit, 3 daughters later and I didn’t think of that! Not sure I want a 4th though 😀

This was a fantastic read mate. I’m reading it for the second time, after going down a Heavy Gear rabbit hole a few weeks back.

This, along with watching Gundam Wing, was super influential for me growing up. I have memories running around the playground as a kid, pretending I was piloting your Screamin’ Victory. It gave me a life-long love of mecha. Soon as I saw those things pop wheels and razz it about, I was sold. Problem is, I had no idea as to the airing schedule here in the UK and so I caught very little and certainly not in chronological order; sometimes the planets would align and I’d catch one. It lived rent-free in my head for years though.

Gundam ’79 is one of my all timers and I’m going to work my way through Votoms once I’ve finished the HG video games. With the incredibly gracious help of Robert Dubois, I even managed to track down an old Marcus miniature – buzzing to get some paint on it.

Thank you for making a somewhat hazy part of my childhood special. You made many little Gear Heads with this thing.

Very glad to hear that. Thank you!

This show aired in argentinian tv during 2002 and has lived rent free in my head all my life, its too sad that mecha never had the chance to take off in north america, we would live in a better timeline, ty for the write up

Thank you for writing this out. And thank you for having worked on this project.

Me and my girl (who introduced me to this back in the’90s) still watch the dvds regularly and I would be lying if I wouldn’t say that the Heavy Gear animation wouldn’t be at least mentioned once every week. (yes we are really still such fans about it).

We still love it, even though cg changed so much over time. We love the story, the characters, the whole concept. So much that we actually started our own (kinda tabletop) roleplaying game, based on this series. We always build up based on this series, eventually having indeed Terra Nova clash with “earthlings” into wars etc (so it’s fun to read that this series was actually intended to go like that).

We still dream for a remake, maybe even a live-action based on this. But at the same time we fear it, knowing how they can turn out due to wanting to be too pleasing for the mainstream crowd.

Thank you again for being part of this, and thank you for writing this out so me and my girl had some background info to chat about Heavy gear some more.

We send you our hugs from Belgium, Europe, where the show had been aired a long long time ago.